Physical Evaluation of the Knee

formulation of the correct diagnosis and initiation of an appropriate

course of treatment. Despite many advances in laboratory and imaging

technology, a thorough history and physical examination remains the

most effective instruments in achieving these goals. The clinician may

establish a provisional diagnosis early in the patient encounter after

hearing only the patient’s presenting complaint and history of present

illness. A detailed history will direct the focus and extent of the

physical examination and aid in refining the diagnosis. Close

interaction with the patient during the history and physical

examination promotes accurate assessment of the patient’s level of

disability and formulation of an individualized treatment plan

appropriate for their expectations and goals for recovery.

explored in a clear, systematic fashion and include discussion of

location, timing, quality, severity, and aggravating/relieving factors.

Pain is the most common complaint that drives orthopaedic patients to

seek medical evaluation. Asking the patient to point to the most

painful area of the knee is a simple way to determine the anatomic

location of the symptoms. The timing of onset should be explored,

because symptoms may start insidiously and slowly progress with a

waxing and waning course, or may start suddenly after a major or minor

traumatic event. The pattern of symptoms may provide immediate insight

regarding a presumptive diagnosis. For example, initially

osteoarthritis may cause aching pain that localizes to one area of the

knee, occurs only after prolonged weight-bearing activities, and is

relieved by short periods of rest. This may be differentiated from

early pain owing to inflammatory arthritis, which may be more diffuse,

constant, and unrelieved by rest. Besides pain, the presence of

mechanical symptoms and subjective instability should be reviewed.

Locking, catching, and popping are suggestive of a meniscal tear, loose

body, or focal lesion of the articular surface. Instability can be

caused by true ligamentous insufficiency or may be owing to reflex

inhibition of the quadriceps from knee pain or effusion. It is

important to inquire about past events specific to the joint, as

patients may not readily recall childhood illnesses or conditions that

affected the knee, and they may not mention previous minor surgical

interventions such as arthroscopy.

paramount. Informed discussions regarding risk-benefit ratios of

potential conservative and surgical treatment options cannot take place

until this is established. Functional deficits should be evaluated in

the context of the patient’s baseline level of physical activity

including activities of daily living, occupational and work-related

activities, and leisure activities (Table 16-1).

As symptoms worsen patients typically exhibit progressive activity

modification and adaptive mechanisms, such as using assistive devices

for ambulation (cane, walker), using the hands to assist in rising from

a chair, and altering stair climbing technique or avoiding stairs

altogether. Standardized physician-administered (e.g., Knee Society

Clinical Rating System) and patient-administered (e.g., Western Ontario

and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index) rating scales can be

useful in evaluating patients’ functional deficits. Perceptions

regarding level of disability may vary greatly between patients with

different occupations or cultural backgrounds. Because of the physical

demands of his work, a laborer may perceive himself to be disabled

earlier in the disease process than a sedentary office worker. Some

patients tolerate lifestyle changes more effectively than others and

may be willing to change careers or give up favorite leisure activities

to avoid surgical treatment.

prescribed and unprescribed, should be discussed. Patients will often

fail to mention treatments such as over-the-counter nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory medications and self-directed therapeutic exercise.

Discovering the

frequency,

duration, and efficacy of all prescribed interventions, including

activity modification, orthotics, physical therapy, pain and

anti-inflammatory medications, and injections, is important for

determining the next step in treatment.

|

TABLE 16-1 History: Assessing Functional Deficits and Disability

|

|

|---|---|

|

and may be included in the history of present illness. Specific inquiry

regarding constitutional symptoms may uncover fever, anorexia, weight

loss, fatigue, and generalized morning stiffness, which are indicative

of an inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis or infection.

The review of systems should also cover other possible sources of knee

symptoms, including the neurovascular system, spine, and adjacent

joints. The hip and spine are common sources of referred pain to the

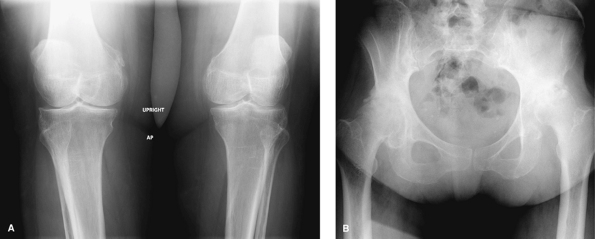

knee (Fig. 16-1). The review of systems should

also be used to identify medical issues that require attention prior to

any surgery, such as undiagnosed cardiac or respiratory disease and

recent or ongoing infections, particularly of the genitourinary tract

and oropharynx.

|

|

Figure 16-1 Radiographs of a 54-year-old patient referred for treatment of severe bilateral knee pain. A:

Standing anteroposterior radiograph of both knees demonstrates mild to moderate osteoarthritis. Note the oblique view of both knees, as the patient could not internally rotate her hips to neutral for the study. B: Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis demonstrates severe arthrosis of both hip joints. Staged bilateral total hip arthroplasty resulted in complete resolution of her symptoms. |

social histories will offer diagnostic clues as well as information

that dictates available treatment options and the manner in which they

are executed. The medical history may reveal an underlying systemic

inflammatory condition as the cause for the knee condition and preclude

nonarthroplasty surgical options. An extensive medical history,

especially cardiac, may eliminate surgical options altogether. A review

of the patient’s medications may identify active medical conditions the

patient failed to discuss previously. In addition, make note of any

medications that should be discontinued perioperatively, such as

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, anticoagulants, and

disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. The social history should

include details of the patient’s current living conditions and whether

the patient will have adequate assistance at home after hospital

discharge. The patient’s use of alcohol, tobacco, or illicit substances

must be documented accurately, as these agents may necessitate

alterations in perioperative medical management or possibly disqualify

the patient from surgical intervention.

evaluation of the patient presenting with knee symptoms must be

completed in a systematic fashion. The order and organization of the

exam is a matter of personal preference, but in general must include

inspection, palpation, range of

motion,

ligamentous exam, and neurologic and vascular evaluation. The

examination should include evaluation of both knees. Normal findings

are most frequently symmetrical, so asymmetry may indicate the presence

of pathology. To minimize guarding during examination of the affected

knee, examine the uninvolved knee first. Avoid areas of known

tenderness and exacerbating maneuvers until as late in the exam as

possible.

clinician lays eyes on the patient. Briefly observing how the patient

moves on the way to the examination room may provide a more candid

glimpse of the patient’s gait and reliance on assistive devices than

when he or she is asked to ambulate during the formal exam. Much can be

learned regarding a patient’s level of physical dysfunction and

disability by general observation during the interview as well as

during the formal examination. General appearance and body habitus must

be noted. Observe the patient’s posture of the spine, hips, and knees

while seated. While removing shoes and socks and getting on and off the

exam table, the patient may exhibit abnormal movement to compensate for

pain or stiffness. Watch carefully for facial expressions and wincing

that indicate pain.

standing. Inspection of the spine may reveal a scoliosis or alteration

of normal lumbar lordosis with associated paravertebral spasm. Check

the range of motion of the lumbar spine with flexion, extension, side

bending, and rotation. Patients with osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine

often experience lumbar pain with extension. The bony landmarks of the

pelvis can be palpated to assess for pelvic obliquity. A fixed pelvic

obliquity owing to lumbosacral disease will not correct when a block is

placed under the apparently short limb. Abductor weakness, often

associated with hip pathology, can be recognized with the Trendelenburg

test. During a single leg stance, the abductor muscles on the

supporting extremity contract to maintain a level pelvis. A positive

test occurs when the abductors are not strong enough to support the

body’s weight and the hemipelvis opposite the supported limb drops

toward the floor.

some indication of the location of the knee pathology. Genu varum

suggests involvement of the medial compartment, whereas genu valgum

suggests involvement of the lateral compartment. During gait these

deformities may prove to be dynamic, with worsening of the varus and

valgus deformities during stance phase observed as lateral and medial

thrusts at the knee, respectively. The presence of a thrust in the

setting of osteoarthritis has prognostic implications, as these knees

demonstrate a propensity for disease progression. A dynamic recurvatum

deformity during stance phase should alert the clinician to the

possibility of an underlying neurologic condition, extensor mechanism

dysfunction, or significant ligamentous laxity. Posture of the ankles

and feet should not be overlooked. Hindfoot bracing for a flexible

planovalgus deformity of the foot and ankle may provide symptomatic

relief for an ipsilateral valgus knee.

component of the examination. The patient’s effort to reduce joint load

at the knee can result in many compensatory gait changes. Pain during

weight bearing causes the patient to limit the amount of time spent in

stance phase of gait, producing an antalgic gait (classic limp), which

is the most common adaptive gait pattern. Decreased cadence may be

observed, which effectively reduces all external moments on the

affected knee. Reduced stride length results from a decrease in forward

reach of the involved extremity in late swing phase, which diminishes

the external sagittal plane moment at the knee during heel strike. An

out-toeing gait may be observed in patients with painful varus

osteoarthritis of the knee, which reduces the adduction moment at the

knee by shortening the moment arm. Likewise, patients may lean the

trunk toward the affected weight-bearing extremity to reduce the moment

arm between their center of gravity and the limb’s mechanical axis.

This should not be confused with the Trendelenburg lurch observed with

hip pathology and concurrent abductor weakness and dysfunction.

exam can be completed with the patient lying supine before focusing on

the knee. Patients with a lumbar radiculopathy may exhibit tenderness

in the region of the sciatic notch. The clinician should perform

maneuvers that place the sciatic nerve under tension, including the

straight leg raise and contralateral straight leg raise tests. Examine

the hips, starting with palpation of the greater trochanter. Localized

tenderness suggests greater trochanteric bursitis, which can present

with referred pain to the lateral thigh and occasionally the lateral

aspect of the knee. The ability to perform an active straight leg raise

against gravity and added resistance should be tested. Groin and

anterior hip or thigh pain with this maneuver may suggest

intra-articular hip pathology. Active side-lying hip abduction may

produce similar symptoms, and patients with advanced hip disease may

not be able to overcome gravity. Passive hip motion may also produce

groin and thigh pain. Loss of hip motion, especially flexion and

internal rotation, is a strong indicator for the presence of advanced

hip pathology.

inspection of the lower extremities should be performed. Muscle tone,

atrophy, and defects in the thigh and calf should be noted. Recording

thigh and calf circumference at fixed distances above and below the

patella allows objective measurement of muscle atrophy. The presence

and severity of peripheral edema should be noted, along with any

pretibial skin changes or varices associated with chronic venous stasis.

reassessed. In thin patients, varus and valgus alignment can be

quantified with a goniometer centered on the anterior aspect of the

patella. Deformities of the thigh and lower leg should not be

overlooked. Many patients will fail to mention remote trauma and

surgery in their history. Healed scars should be discussed with the

patient, because they may indicate the presence of posttraumatic or

surgical deformities that are not outwardly visible, especially in

overweight and obese patients. Scars about the knee may provide insight

regarding the underlying diagnosis and should be accurately documented

for preoperative planning. Skin rashes

may

suggest a systemic cause for the patient’s knee pathology. When present

over the knee, rashes are associated with increased risk of surgical

site infection and should be treated prior to operative intervention.

assessed with the patient supine and the knee in extension and in

flexion. Knee effusions can be assessed by compressing the

suprapatellar pouch and assessing ballottement of the patella.

Effusions must be differentiated from synovial thickening or bogginess,

which suggests inflammatory arthritis. Although nonspecific, slight

skin warmth over the knee relative to the adjacent calf and thigh can

indicate the presence of a generalized synovitis. Localized swelling

may represent the site of isolated pathology or may be an indicator of

a more remote or generalized process. For example, localized medial

joint line swelling may be identified in the presence of a meniscal

cyst with an underlying meniscal tear. In contrast, swelling and

fullness in the popliteal fossa at or medial to the midline commonly

represents a popliteal (Baker) cyst. A popliteal cyst can be associated

with any process that produces a chronic effusion, such as a remote,

isolated process that results in synovitis, or a generalized condition

such as inflammatory arthritis.

gross anatomy of the knee joint is imperative for diagnosing underlying

knee pathology. The normal anatomic landmarks of the anterior knee may

be obscured by a large knee effusion or diffuse soft tissue swelling.

Bony landmarks should be identified and palpated, including the femoral

epicondyles, fibular head, tibial tubercle, patellar margins, and

medial and lateral joint lines. Bony thickening at the joint line

suggests the presence of osteophytes. Note areas of localized

tenderness. Soft tissue structures adjacent to or crossing the knee

joint, such as the pes anserine bursa and hamstring tendons, are often

significant pain generators and should not be ignored. The integrity of

the extensor mechanism can be checked with an isometric quadriceps

contraction and straight leg raise.

position. By convention, full extension is 0 degrees, with up to 10

degrees of hyperextension considered normal. Flexion in the normal

adult knee is to approximately 135 or 140 degrees, with 105 degrees

required for normal performance of activities of daily living in

Western societies. Comparison of active and passive range of motion is

necessary to distinguish between joint contracture and extensor lag. A

flexion contracture is identified by the inability to passively

position the knee in full extension. Causes include soft tissue

contracture such as hamstring and gastrocnemius tightness, and

mechanical block from a meniscus tear, loose body, or osteophyte

formation. A discrepancy in active and passive extension represents an

extensor lag and may be attributable to pain or extensor mechanism

dysfunction from weakness or disruption. A knee with a large joint

effusion assumes a 15- to 25-degree resting position and can cause loss

of both active and passive flexion and extension. During range of

motion assessment, crepitus is a common finding and may be localized to

a particular compartment by palpation of the knee.

the patient standing. The Q-angle (quadriceps angle), which is the

acute angle formed by intersecting lines drawn from the center of the

tibial tubercle to the center of the patella and from the center of the

patella to the anterior-superior iliac spine, is a measure of the

lateral pull of the quadriceps on the patella. A Q-angle >15 to 17

degrees is associated with altered patellofemoral mechanics and

anterior knee pain. Complex torsional deformities of the lower

extremity, most commonly increased femoral anteversion, can be

associated with an increased Q-angle and should be evaluated during

assessment of hip motion. Tracking of the patella in the femoral sulcus

should be observed during gait and with both active and passive knee

extension. Excessive lateral movement of the patella as it exits the

femoral sulcus during terminal knee extension is known as the J-sign.

Typically the patella does not articulate with the femoral sulcus until

the knee is flexed 25 to 30 degrees, so patellar tilt and

medial-lateral patellar glide should be assessed with the knee in a

slightly flexed position. Lack of patellar mobility, as well as lateral

tracking with crepitus as the knee flexes past 30 degrees, may indicate

the presence of patellofemoral arthritis. Patella alta and baja can be

assessed clinically with the knee flexed 90 degrees over the end of the

exam table. Tenderness of the medial and lateral facets of the patella

can be evaluated, but may be falsely positive in the presence of

interposed synovitis.

the medial and lateral joint lines. Tenderness at the apex of a

meniscal tear is a common finding owing to its peripheral nerve fibers

and localized synovitis. Numerous provocative tests exist for

evaluation of the menisci, most of which attempt to reproduce pain or

palpable clicks by trapping the abnormally mobile or torn meniscus

between two joint surfaces. Of these, the McMurray test is probably the

most widely used. With the patient supine, the knee is brought into

deep flexion and maximal external rotation with one hand on the foot.

The opposite hand is placed on the knee with the fingers over the

posteromedial joint line, and the knee is brought into extension while

a varus force is applied to the knee. Posteromedial pain and a palpable

or audible click indicate a positive test. The maneuver can be repeated

for the posterolateral meniscus by internally rotating the tibia and

applying a valgus force as the knee is passively extended.

establishing a diagnosis and formulating potential conservative and

operative treatment plans. The clinician must be able to distinguish

isolated ligament deficiency from complex and rotational instability

patterns. However, exhaustive review of the many specific tests for

ligament integrity and complex instability patterns of the knee are

beyond the scope of this chapter. Simple evaluation of the cruciate and

collateral ligaments is presented here. The reader should refer to a

comprehensive source for a complete review of the ligamentous

examination of the knee.

to anterior movement of the tibia on the femur. Its integrity is best

evaluated with the Lachman and anterior drawer tests.

The

Lachman test is performed with the knee in 30 degrees of flexion. With

one hand stabilizing the femur, anteriorly directed pull is applied to

the tibia. A positive test results in excessive anterior translation of

the tibia with a soft end point. In knees that are difficult to

examine, such as those of obese patients, or in the setting of acute

pain or swelling, the anterior drawer test may be useful. With the hip

flexed 45 degrees and the knee flexed 90 degrees, the foot is

stabilized on the exam table and again anteriorly directed pull is

applied to the tibia. The posterior cruciate ligament is the primary

restraint to posterior movement of the tibia on the femur. It is best

evaluated with the posterior drawer test, performed with the extremity

in the same position used for the anterior drawer test. A positive test

is marked by posterior subluxation of the tibia on the femur when a

posteriorly directed force is applied to the anterior tibia.

applying simple varus and valgus stresses to the knee in both full

extension and again with the knee flexed 30 degrees. In full extension,

the collateral ligaments, posterolateral capsule, and posteromedial

capsule are all in a taut position. Therefore, varus and valgus

stresses applied with the knee in full extension tests the integrity of

the collateral ligaments as well as the posterolateral and

posteromedial capsular structures. The posterior capsular structures

relax when the knee is flexed 30 degrees, better isolating the

collateral ligaments in resisting varus and valgus stresses. The

cruciate ligaments are also taut in extension, so the presence of

significant laxity to varus or valgus stress in full extension suggests

cruciate ligament disruption in addition to collateral ligament

disruption.

varus-valgus instability, the clinician must distinguish true

ligamentous insufficiency from pseudolaxity. For example, varus knees

with osteoarthritis typically exhibit articular cartilage and bone loss

in the medial compartment. Laxity to varus stress could represent

lateral collateral ligament insufficiency or rotation of the tibia into

varus as the medial femoral condyle settles into the defect in the

medial tibial plateau. Conversely, laxity to valgus stress may

represent correction of varus alignment as the tibia rotates back to

neutral position. Inability to passively correct a coronal plane

deformity may indicate the presence of long-standing disease with

secondary medial or lateral soft tissue contracture that requires

release at the time of reconstruction.

not be neglected. Neurologic evaluation should include muscle testing,

sensory examination, and assessment of deep tendon reflexes. Prior

inspection should have identified atrophy or loss of muscle tone in the

thigh and leg. Strength testing is performed by resisted isometric

contraction of all major muscle groups, including hip flexion,

extension, and abduction; knee flexion and extension; and ankle

dorsiflexion and plantarflexion. Sensation can be evaluated by testing

light touch, paying special attention to deficits in a dermatomal

distribution. Deep tendon reflexes can be tested at the knee and ankle.

The patellar reflex is predominantly an L4 reflex, and the Achilles

reflex is an S1 reflex. Vascular assessment must include examination of

the skin for signs of peripheral vascular disease, such as smooth shiny

skin with hair loss, skin and subcutaneous soft tissue atrophy, and

ulcerations. Palpation of peripheral pulses should include femoral,

popliteal, posterior tibial, and dorsalis pedis pulses.

N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, et al. Validation study of WOMAC: a

health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient

relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with

osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988; 15:1833-1840.

JP, Hudak PL, Hawker GA, et al. The moving target: a qualitative study

of elderly patients’ decision-making regarding total joint replacement

surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004; 86:1366-1374.