Osteochondral Defect of the Talus

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Osteochondral Defect of the Talus

Osteochondral Defect of the Talus

Marc D. Chodos MD

Description

-

OCDs of the talus represent damage to the articular surface of the talar dome in the ankle joint.

-

The talus is the 3rd most common site (after the knee and elbow) of osteochondral lesions.

-

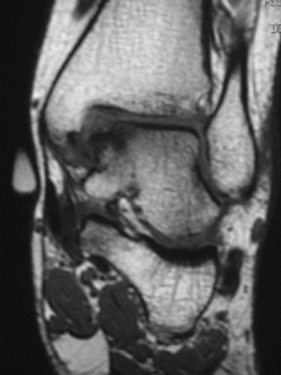

The most common sites are the posteromedial (53%) (Fig. 1) and anterolateral (46%) talar dome (1).

-

Most classification systems are based on lesion descriptions by Berndt and Harty (2):

-

Stage 1: Subchondral bone compression

-

Stage 2: Partially detached osteochondral fragment

-

Stage 3: Detached but stable/nondisplaced osteochondral fragment

-

Stage 4: Detached and displaced fragment

-

Stage 5: Subchondral cyst (added by Loomer et al.) (1)

-

General Prevention

No clear method is available for preventing this

disorder, although early surgical treatment of chronic ankle

instability may prevent the development of OCD attributable to

instability.

disorder, although early surgical treatment of chronic ankle

instability may prevent the development of OCD attributable to

instability.

Epidemiology

-

Most patients who develop OCDs are in their 2nd–4th decades, with a mean age of 26.9 years (3).

-

65% are male (3).

Incidence

-

0.09% of all fractures (4)

-

0.1% of all talus fractures (4)

-

4% of all osteochondral lesions (5)

Fig. 1. Coronal T1-weighted image of the ankle, showing a medial talar OATS.

Fig. 1. Coronal T1-weighted image of the ankle, showing a medial talar OATS.

Risk Factors

-

Most OCDs are traumatic in origin.

-

Therefore, ankle fracture, sprain, and chronic ankle instability are risk factors.

Genetics

Weak evidence suggests that a genetic component might be involved in some OCDs (5).

Pathophysiology

OCDs can be produced in cadaveric models by shear and compression forces (2).

Etiology

-

Most commonly caused by trauma:

-

Acute: Ankle fracture or sprain

-

Chronic: Recurrent injury from chronic ankle instability

-

Lateral OCD is associated with a recognized traumatic episode in 93% of cases (3).

-

Medial OCD is associated with a recognized traumatic episode in 61% of cases (3).

-

-

Other possible causes include ischemic events (AVN).

Associated Conditions

-

Ankle fracture

-

Ankle sprain

-

Chronic ankle instability

Signs and Symptoms

History

-

Assess for:

-

History of previous ankle injury

-

History of ankle instability or sprains

-

Mechanical symptoms (locking, catching)

-

Physical Exam

-

Perform general foot and ankle examination.

-

Specific areas for concentration:

-

Palpate for ankle swelling or effusion.

-

Evaluate for tenderness over the talar dome.

-

Examine for ankle instability (anterior drawer test, talar tilt test) or evidence of general ligamentous laxity.

-

Examine for crepitus or mechanical signs with ankle ROM.

-

-

Make sure the patient does not have other

abnormalities that explain chronic ankle pain, including peroneal

tendon subluxation, fracture of the lateral process of the talus, 5th

metatarsal fracture, syndesmosis sprain, or tarsal coalition.

Tests

The diagnosis of OCD most frequently depends on obtaining an imaging study: Plain radiographs or CT, MRI, or bone scans.

Imaging

-

Weightbearing radiographs should be obtained initially.

-

Sensitivity = 0.70, specificity = 0.94 (6)

-

Although OCDs frequently are not well

visualized on plain radiographs, this modality is inexpensive, easy to

obtain, and can help rule out other abnormalities.

-

-

CT:

-

Sensitivity = 0.81, specificity = 0.99 (6)

-

If a lesion is seen on plain radiographs,

then a CT scan provides the greatest certainty of all imaging

modalities that the lesion is real and an OCD (i.e., best positive

predictive value). -

Best method for accurately characterizing the size and extent of a defect

-

-

MRI:

-

Sensitivity = 0.96, specificity = 0.99 (6)

-

A negative MRI provides the greatest

certainty of all imaging modalities that no lesion exists (i.e., best

negative predictive value). -

Tends to overestimate the size of a lesion because of bone marrow edema

-

Metal artifact can make MRI difficult to interpret in certain cases.

-

Best modality for finding associated soft-tissue abnormalities

-

-

No difference in the effectiveness of CT and MRI in diagnosing an OCD (6)

Diagnostic Procedures/Surgery

-

Arthroscopy provides the best and most direct method for evaluating the articular surface and treating the abnormality.

-

Problems with arthroscopy include:

-

Surgeon-dependent

-

Cannot evaluate subchondral abnormalities

-

Invasive

-

Pathological Findings

-

When not displaced, a chronic osteochondral fragment often is attached to the defect by fibrous tissue.

-

If the subchondral bone is violated, the defect attempts to heal with fibrous tissue or fibrocartilage.

-

If the subchondral bone is not violated, no healing occurs.

-

Although the cartilage cap remains viable (7), the osseous component of a displaced OCD is avascular and has a low potential to heal in chronic cases.

-

Differential Diagnosis

-

The differential diagnosis includes any cause of chronic pain in the region of the ankle joint:

-

Occult fracture (5th metatarsal, lateral process of talus, medial or lateral malleolus)

-

Ankle or syndesmosis sprain

-

Chronic ankle instability

-

Peroneal tendon subluxation

-

Anterior ankle impingement

-

Tarsal coalition

-

Ankle or subtalar joint synovitis

-

Posterior tibialis tendinitis

-

P.287

General Measures

-

Nonoperative management consisting of

cast or boot immobilization can be attempted for stage 1, stage 2, and

some stage 3 lesions.-

Success rate is ~50% (3).

-

Delaying surgical intervention for chronic OCD does not appear to alter results of later surgery.

-

Pediatric Considerations

-

Children are thought to have better healing potential than adults.

-

Although nonoperative management is

recommended more often for children, the results are not necessarily

better than those for adults. -

Letts et al. (8) found that only 9 of 24 (37.5%) pediatric patients with an OCD managed without surgery had a good or excellent result.

Activity

-

Nonoperative management recommendations range from activity modification alone to nonweightbearing in a cast.

-

Microfracture or drilling: 4–6 weeks of nonweightbearing is recommended to allow the defect to heal, with ankle ROM encouraged.

-

Any procedure that requires an osteotomy necessitates nonweightbearing until the osteotomy heals (4–8 weeks).

-

ROM usually is started 2–6 weeks after surgery, depending on the quality of the osteotomy fixation.

-

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

Ankle ROM exercises, peroneal strengthening, progressive ambulation, and proprioception training

Surgery

-

Several surgical options exist, but the

indications for 1 procedure over another are not well defined by

evidence-based medicine. -

Procedures that reduce and stabilize the displaced fragment:

-

Usually recommended only for lesions that are large enough to be amenable to internal fixation

-

Acute fractures do better than chronic lesions.

-

-

Procedures that stimulate fibrocartilage

formation include débridement, curettage, and microfracture or drilling

of the subchondral bone.-

Generally recommended as the initial

method of surgical treatment because it can be done arthroscopically

with minimal morbidity and is associated with an 85% success rate (3). -

Loose bodies, fibrous tissue, and unstable cartilage are débrided.

-

Subchondral bone is penetrated to allow bleeding and fibrin clot formation.

-

It is thought that mesenchymal stem cells in the clot lead to the formation of fibrocartilage.

-

-

Although biomechanically inferior to hyaline cartilage, fibrocartilage formation appears to be sufficient for smaller lesions.

-

Defects with a surface area <1 cm2 seem to have better results than larger lesions.

-

-

Procedures that transfer hyaline cartilage to the defect: OATS/mosaicplasty, allograft transfer

-

Generally recommended for large lesions or lesions that fail other forms of treatment

-

Osteotomy usually is required as part of the surgical approach.

-

OATS/mosaicplasty:

-

Osteochondral tissue harvested from a

remote nonloadbearing site (usually the ipsilateral knee) and

transplanted into talar defect -

Limited by the amount of donor tissue that can be harvested

-

94% good to excellent results (9)

-

-

Allograft transfer:

-

Osteochondral tissue harvested from fresh allograft talus and transplanted into the defect

-

Best for large (>3 cm2) lesions, as an alternative to arthrodesis (10)

-

66% success rate (11)

-

-

-

Procedures that regrow hyaline cartilage, such as autologous chondrocyte transfer:

-

Cartilage is harvested (usually from the knee) and grown in culture.

-

Once enough cells are available, the chondrocytes are reimplanted into the defect.

-

Because cells are grown in vitro, defect size is not limited with this procedure.

-

Osteotomy usually is required as part of the surgical approach.

-

-

1st- and 2nd-generation techniques rely

on injection of the cell suspension under a periosteal flap or collagen

membrane that is sewn and glued over the defect (12). -

3rd-generation techniques rely on a 3D bioscaffold to contain the cells instead of a periosteal flap (7).

-

Short-term clinical results generally are

good, although biopsies of treated lesions often show fibrocartilage,

not hyaline cartilage. -

In the future:

-

More complex scaffolds that better replicate the microarchitecture of articular cartilage may become available.

-

Growth factors and the use of mesenchymal stem cells also will be important in refining the procedure and improving results.

-

-

-

Other surgical options: Concurrent chronic ankle instability should be addressed with ligament reconstruction.

Prognosis

With proper treatment, the prognosis generally is good.

Complications

Complications include malunion or nonunion of an osteotomy, persistent pain, stiffness, and arthritis.

Patient Monitoring

The patient is followed regularly to make sure that ROM

is regained, any osteotomies heal, and clinical resolution of symptoms

occurs.

is regained, any osteotomies heal, and clinical resolution of symptoms

occurs.

References

1. Loomer R, Fisher C, Lloyd-Smith R, et al. Osteochondral lesions of the talus. Am J Sports Med 1993;21:13–19.

2. Berndt AL, Harty M. Transchondral fractures (osteochondritis dissecans) of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg 1959;41A:988–1020.

3. Verhagen

RAW, Struijs PAA, Bossuyt PMM, et al. Systematic review of treatment

strategies for osteochondral defects of the talar dome. Foot Ankle Clin 2003;8:233–242.

RAW, Struijs PAA, Bossuyt PMM, et al. Systematic review of treatment

strategies for osteochondral defects of the talar dome. Foot Ankle Clin 2003;8:233–242.

4. Giannini S, Vannini F. Operative treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talar dome: current concepts review. Foot Ankle Int 2004;25: 168–175.

5. Santrock RD, Buchanan MM, Lee TH, et al. Osteochondral lesions of the talus. Foot Ankle Clin 2003;8:73–90.

6. Verhagen

RAW, Maas M, Dijkgraaf MGW, et al. Prospective study on diagnostic

strategies in osteochondral lesions of the talus. Is MRI superior to

helical CT? J Bone Joint Surg 2005;87B:41–46.

RAW, Maas M, Dijkgraaf MGW, et al. Prospective study on diagnostic

strategies in osteochondral lesions of the talus. Is MRI superior to

helical CT? J Bone Joint Surg 2005;87B:41–46.

7. Giannini

S, Buda R, Grigolo B, et al. The detached osteochondral fragment AS a

source of cells for autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) in the

ankle joint. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2005;13: 601–607.

S, Buda R, Grigolo B, et al. The detached osteochondral fragment AS a

source of cells for autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) in the

ankle joint. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2005;13: 601–607.

8. Letts M, Davidson D, Ahmer A. Osteochondritis dissecans of the talus in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2003;23:617–625.

9. Hangody

L, Kish G, Modis L, et al. Mosaicplasty for the treatment of

osteochondritis dissecans of the talus: two to seven year results in 36

patients. Foot Ankle Int 2001;22:552–558.

L, Kish G, Modis L, et al. Mosaicplasty for the treatment of

osteochondritis dissecans of the talus: two to seven year results in 36

patients. Foot Ankle Int 2001;22:552–558.

10. Raikin SM. Stage VI: massive osteochondral defects of the talus. Foot Ankle Clin 2004;9: 737–744.

11. Gross

AE, Agnidis Z, Hutchison CR. Osteochondral defects of the talus treated

with fresh osteochondral allograft transplantation. Foot Ankle Int 2001;22:385–391.

AE, Agnidis Z, Hutchison CR. Osteochondral defects of the talus treated

with fresh osteochondral allograft transplantation. Foot Ankle Int 2001;22:385–391.

12. Giannini S, Buda R, Grigolo B, et al. Autologous chondrocyte transplantation in osteochondral lesions of the ankle joint. Foot Ankle Int 2001; 22:513–517.

Codes

ICD9-CM

732.7 Osteochondritis dissecans

Patient Teaching

The patient should be actively involved in the

decision-making process, with a clear understanding of the risks and

benefits of surgical and nonsurgical treatments.

decision-making process, with a clear understanding of the risks and

benefits of surgical and nonsurgical treatments.

FAQ

Q: How are unstable OCD lesions of the ankle treated?

A:

A patient with an unstable, displaced OCD of the talus typically

presents with mechanical symptoms, including locking or giving way of

the ankle because of the loose body. Such lesions have poor prognoses

with nonoperative treatment and typically are addressed with

arthroscopic surgery. Stable OCDs may respond to a short trial of rest,

immobilization, and physical therapy; failures are treated surgically.

A patient with an unstable, displaced OCD of the talus typically

presents with mechanical symptoms, including locking or giving way of

the ankle because of the loose body. Such lesions have poor prognoses

with nonoperative treatment and typically are addressed with

arthroscopic surgery. Stable OCDs may respond to a short trial of rest,

immobilization, and physical therapy; failures are treated surgically.