Musculoskeletal Infection

Editors: Berquist, Thomas H.

Title: Musculoskeletal Imaging Companion, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Chapter 11 – Musculoskeletal Infection

Chapter 11

Musculoskeletal Infection

Thomas H. Berquist

Basic Concepts

Key Facts

-

Musculoskeletal infections may present with acute rapidly progressive onset or in a more insidious fashion (Table 11-1).

Infections may occur from hematogenous spread, spread from a contiguous

source, direct implantation (i.e., puncture wound), or after trauma or

surgery. -

Insidious onset of infection often follows trauma or surgical intervention.

-

Clinical presentation is dependent on age, virulence of organisms, patient condition, site of involvement, and circulation (Table 11-2).

-

Early detection and evaluation of the extent of involvement are essential for proper treatment and optimal prognosis.

-

Imaging of musculoskeletal infection usually requires a multimodality approach.

-

Radiography: Soft tissue swelling or

joint effusion may be the only findings. Significant bone destruction

must be present before radiographs are positive. -

Radionuclide scans: Bone scanning is

sensitive and can detect abnormalities early, but there is less

anatomic detail and findings are not specific. Techniques include

three-phase technetium-99m-methylene diphosphate, gallium-67-, and

indium- or technetium-labeled white blood cell studies, technetium

antigranulocyte antibody scans, and positron emission tomography (PET).P.750TABLE 11-1 INFECTIONS: TERMINOLOGY AND CATEGORIESTerm/Conditions Clinical/Image Features Osteomyelitis Infections in bone and marrow

Bacterial most commonInfective osteitis Cortical infection. Often associated with marrow or soft tissue infection. Infective periostitis Periosteal infection often with marrow and cortex involved Soft tissue infection Involves skin, subcutaneous tissues, muscles, tendons, ligaments, fascia, or bursae Sequestrum Segment of necrotic bone separated from viable bone by granulation tissue Involucrum Living bone around sequestrum Cloaca Tract through viable bone Sinus Tract from infected region to skin Fistula Abnormal communication between two internal organs or internal organs and skin Brodie abscess Sharply defined focus of osteomyelitis Garré sclerosing osteomyelitis Sclerotic nonpurulent infection with intense periosteal reaction Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis Subacute or chronic infection common in children. May be associated with SAPHO. Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis and osteitis (SAPHO) Palmoplantar pustulosis, articular, and hyperostosis and osteitis (SAPHO) periosteal inflammation.

Chronic course involving chest wall, spine, long bones, large and small joints.SAPHO, synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis. -

Computed tomography (CT): cortical and marrow involvement along with sequestra and cloaca detection.

-

Ultrasound: soft tissue infection, abscess formation, foreign body localization, and aspirations.

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): MRI is

particularly suited for evaluation of early bone or soft tissue

infection. Contrast is superior to CT, and anatomic detail is superior

to radionuclide scans. We routinely add contrast-enhanced

fat-suppressed T1-weighted images. -

Aspiration/biopsy: Regardless of the

imaging technique used, joint aspiration or synovial or bone biopsy

under fluoroscopic or ultrasound guidance may be required to isolate

the organism.

-

P.751

|

TABLE 11-2 COMMON ORGANISMS IN MUSCULOSKELETAL INFECTIONS

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Suggested Reading

Berquist TH, Broderick DF. Musculoskeletal infections. In: Berquist TH, ed. MRI of the musculoskeletal system, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:916–947.

Resnick D. Osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and soft tissue infection: Mechanisms and situations. In: Resnick D. Diagnosis of bone and joint disorders, 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:2510–2624.

P.752

Osteomyelitis

Key Facts

-

Early diagnosis and management are essential to avoid irreversible bone or articular damage.

-

Hematogenous osteomyelitis is more common in children than in adults and most frequently involves the lower extremities.

-

Metaphyseal regions, near the physis, are most commonly involved.

-

The physis serves a protective function

preventing infection from entering the epiphysis and, depending on

joint anatomy, the joint from ages 1 to 16 years. -

Imaging of osteomyelitis requires a multimodality approach (Table 11-3).

-

Routine radiographs: may show soft tissue swelling. Bone changes may be inapparent early.

-

Radionuclide scans: A positive

technetium-99m scan is not specific, but a negative scan excludes the

diagnosis. Combined indium-111 or technetium-labeled leukocytes and

technetium-99m scans are more specific. PET may also be useful. -

CT: cortical detail, sequestra, and cloacae

-

MRI: T1- and T2-weighted magnetic

resonance (MR) images are sensitive and can detect changes of infection

early. Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images are routinely added in

our practice. Anatomic detail is superior to radionuclide scans.

-

|

TABLE 11-3 IMAGING APPROACHES FOR OSTEOMYELITIS

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||

P.753

|

|

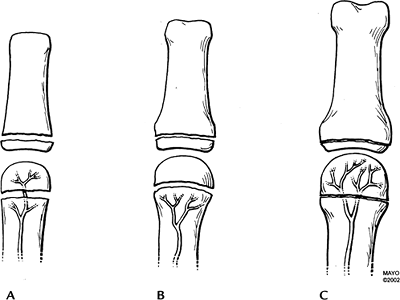

FIGURE 11-1 The vascular supply to the metaphysis and epiphysis in infants (A), children (B), and adults (C). The physis serves a protective function for the epiphysis from ages 1 to 16 years (B).

|

|

|

FIGURE 11-2

Anteroposterior (AP) radiograph demonstrating the characteristic appearance of osteomyelitis with a lytic lesion in the metaphysis (arrow) and periosteal reaction along the fibula (arrowheads). |

P.754

Suggested Reading

Bonakdapour A, Gaines VD. The radiology of osteomyelitis. Orthop Clin North Am 1983;14:21–37.

Gold RH, Hawkins RA, Katz BD. Bacterial osteomyelitis: Findings on plain film, CT, MRI, and scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1991;157:365–370.

P.755

Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis

Key Facts

-

Characterized by exacerbation and remissions.

-

May occur at any age but most common in children 5 to 10 years of age.

-

Patients present with pain, swelling, and tenderness in areas of skeletal involvement.

-

The femoral metaphysis, tibia, and medial clavicles are most commonly involved.

-

Organisms are difficult to isolate. However, Propionibacterium acne, Corynebacterium, and pneumococci have been identified.

-

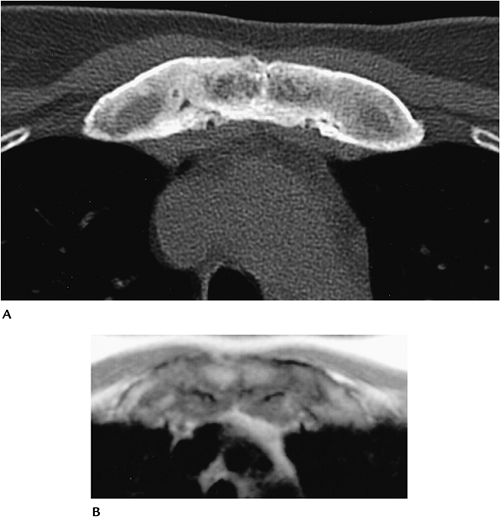

Imaging features show sclerosis of the medial clavicles on radiographs and CT. MR features are nonspecific.

|

|

FIGURE 11-3 Axial CT (A) and T1-weighted MR (B) images demonstrate thickening and sclerosis of the medial clavicles and sternocostal junctions.

|

P.756

Suggested Reading

Demharter

J, Bohndorf K, Michl W, et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal

osteomyelitis: Radiological and clinical investigation in 5 cases. Skel Radiol 1997;26:579–588.

J, Bohndorf K, Michl W, et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal

osteomyelitis: Radiological and clinical investigation in 5 cases. Skel Radiol 1997;26:579–588.

P.757

Sapho (Synovitis, Acne, Pustulosis, Hyperostosis, Osteitis)

Key Facts

-

There is controversy as to whether SAPHO represents a syndrome or group of disorders.

-

Most consider SAPHO a group of disorders

that include chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Skin lesions

may be present for 2 years before osteoarticular findings appear. -

Presentations differ depending on patient age.

-

Children and young adults: present with

features similar to those in chronic recurrent multifocal

osteomyelitis. Lytic metaphyseal changes in long bones early. Tibia,

fibula, and femur most commonly involved followed by the medial

clavicles, sacroiliac joints, and spine. -

Adults: anterior chest wall osteitis in

69% to 90%. Nonspecific discitis in 33%. Unilateral sacroiliac joint

involvement in 13% to 52%, long bones in 30%, and flat bones in 10%.

-

-

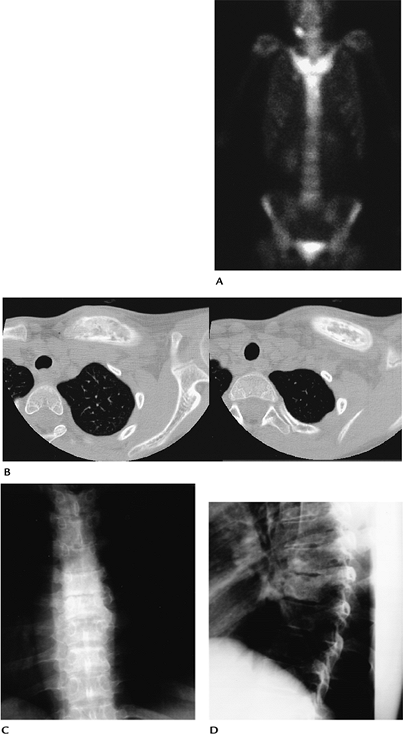

CT and MR most useful for diagnosis.

P.758

|

|

FIGURE 11-4 SAPHO. (A) Radionuclide scan demonstrates intense uptake in the medial clavicles and sternum. (B) Axial CT image demonstrates thickening and sclerosis of the clavicle. AP (C) and lateral (D) radiographs of the spine demonstrate vertebral sclerosis and endplate irregularity caused by discitis.

|

P.759

Suggested Reading

Earwalker JWS, Cotton A. SAPHO: Syndrome or concept? Imaging findings. Skel Radiol 2003;32:311–327.

Hayem G, Bouchard-Chabot A, Benali K, et al. SAPHO syndrome: Long-term follow-up study of 120 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1999;293:159–171.

P.760

Osteomyelitis—Violated Tissue

Key Facts

-

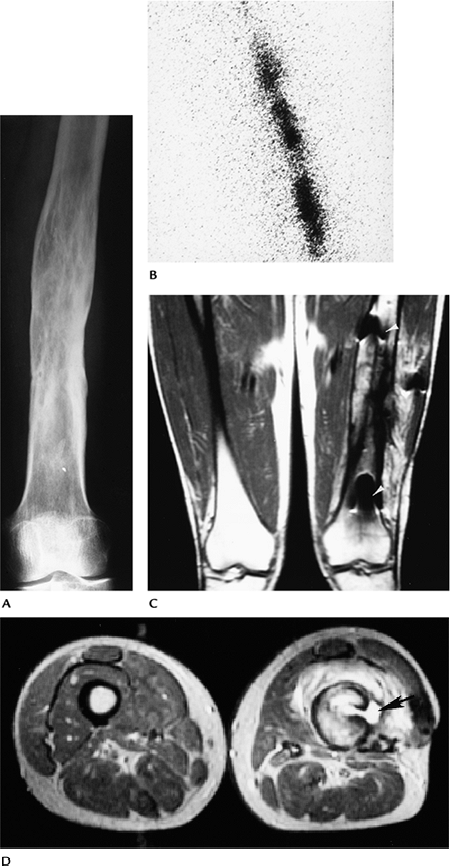

Osteomyelitis may follow trauma, surgery, and puncture wounds with extension from soft tissue foci.

-

Clinical presentation is more confusing and imaging is more difficult, especially when bone and soft issue anatomy is distorted.

-

Orthopedic appliances may cause artifacts on MR and CT images, reducing accuracy.

-

Radionuclide scans may remain positive for up to 10 months after trauma or surgery.

-

Imaging should begin with radiographs.

When there is no metal present, MRI is the technique of choice.

Leukocyte or antigranulocyte antibody scans, and more recently PET,

provide an alternative with or without metal.

P.761

P.762

|

|

FIGURE 11-5 Posttraumatic osteomyelitis. (A) AP radiograph showing posttraumatic deformity with no definite destruction to suggest infection. (B) Indium-111–labeled white blood cell study showing increased uptake caused by infection. (C) Coronal T1-weighted MR image showing decreased signal intensity in the diaphysis with foci of metal artifact (arrowheads). (D) Axial T2-weighted image showing high signal intensity fluid extending through the cortex into a juxtacortical abscess (arrow).

|

P.763

|

|

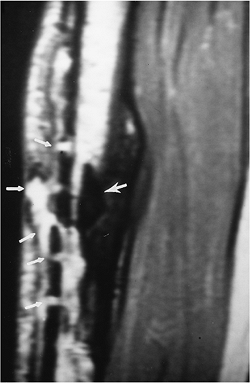

FIGURE 11-6

Old tibial fracture with plate and screw fixation removed because of infection. Sagittal T2-weighted image demonstrates a sequestrum (arrow) with fluid exiting the old pin tracts (small arrows) and a long abscess cavity anteriorly. |

Suggested Reading

Guhlmann

A, Recht-Krause D, Suger G, et al. Chronic osteomyelitis detected with

FDG PET and correlation with histologic findings. Radiology 1998;206:749–754.

A, Recht-Krause D, Suger G, et al. Chronic osteomyelitis detected with

FDG PET and correlation with histologic findings. Radiology 1998;206:749–754.

Jacobson

AF, Harley JD, Lypsky BA, et al. Diagnosis of osteomyelitis in the

presence of soft tissue infection and radiographic evidence of osseous

abnormalities: Value of leukocyte scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1991;157:807–812.

AF, Harley JD, Lypsky BA, et al. Diagnosis of osteomyelitis in the

presence of soft tissue infection and radiographic evidence of osseous

abnormalities: Value of leukocyte scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1991;157:807–812.

Kaim

A, Ledermann HP, Bongartz G, et al. Chronic posttraumatic osteomyelitis

in the lower extremity: Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and

combined bone scintigraphy/immune scintigraphy with radiolabeled

monoclonal antigranulocyte antibodies. Skel Radiol 2000;29:378–386.

A, Ledermann HP, Bongartz G, et al. Chronic posttraumatic osteomyelitis

in the lower extremity: Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and

combined bone scintigraphy/immune scintigraphy with radiolabeled

monoclonal antigranulocyte antibodies. Skel Radiol 2000;29:378–386.

P.764

Joint Space Infection

Key Facts

-

Infectious arthritis generally is monoarticular and, like osteomyelitis, most commonly involves the lower extremities.

-

Children are more likely to present with

fever, chills, and inability to bear weight compared with adults in

whom presentation may be more subtle. -

Early detection is important to prevent bone loss and joint deformity.

-

Joint space and bone changes occur early

with pyogenic infection and late with less aggressive infections such

as tuberculosis or atypical mycobacterial infections. -

Imaging features

-

Radiographs: joint effusion and soft tissue swelling. Joint space widening early, before cartilage destruction.

-

Radionuclide scans: increased uptake early, but nonspecific.

-

MRI: joint effusion on T2-weighted images and early bone and cartilage changes. Findings do not provide specific information (Tables 11-4 and 11-5).

-

Joint aspiration: performed under ultrasound or fluoroscopic guidance to isolate organism.

-

|

TABLE 11-4 MAGNETIC RESONANCE FEATURES OF JOINT SPACE INFECTION

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

TABLE 11-5 IMAGING APPROACHES TO JOINT SPACE INFECTION

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||

P.765

|

|

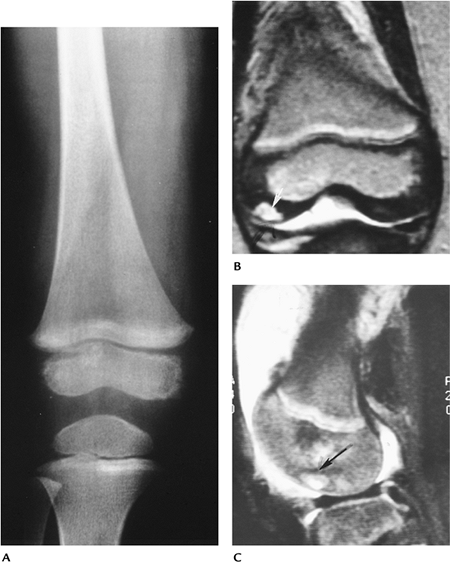

FIGURE 11-7 Joint space infection with extension to the epiphysis. (A) Routine radiograph is normal. T2-weighted coronal (B) and sagittal (C) images showing joint effusion and high signal intensity (arrow) in the epiphysis caused by secondary osteomyelitis.

|

Suggested Reading

Graif M, Schweitzer ME, Deely D, et al. The septic versus nonspecific inflamed joint. MR characteristics. Skel Radiol 1999;28:616–620.

P.766

Soft Tissue Infection

Key Facts

-

Soft tissue infection may be deep or

superficial. Most soft tissue infections are related to inoculation by

a puncture wound, ulcer, or contamination of a skin abrasion.

Cellulitis is an infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues. The

organism usually is Staphylococcus or Streptococcus. Deep infections may involve muscle (myositis) or fascia (necrotizing fasciitis). -

Soft tissue abscesses are well-defined

fluid collections. Pyogenic abscesses tend to have thick walls compared

with thin-walled tuberculous abscesses. -

Infection also may involve bursae and tendon sheaths.

-

Imaging approaches (Table 11-6)

-

Routine radiographs: Soft tissue swelling, subcutaneous edema ulceration, or gas in the soft tissues may be identified.

-

Ultrasound: Fluid collections, foreign bodies, and abscesses can be identified and aspirated or drained.

-

CT: subtle gas in soft tissue planes (necrotizing fasciitis).

-

MRI: Superior tissue contrast and

multiple image planes with T1- and T2-weighted images identify

infection and extent of involvement. Gadolinium enhancement occurs in

areas of inflammation and walls of abscess cavities.

-

|

TABLE 11-6 IMAGING APPROACHES TO SOFT TISSUE INFECTIONS

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||

P.767

|

|

FIGURE 11-8 Lateral radiograph of the foot in a diabetic showing gas in the soft tissues (arrow) caused by infection.

|

P.768

|

|

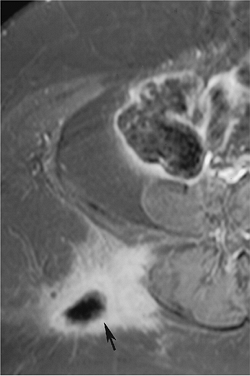

FIGURE 11-9 Gluteal abscess. Contrast-enhanced fat suppressed T1-weighted image demonstrates a thick-walled pyogenic abscess (arrow) with soft tissue inflammation.

|

P.769

|

|

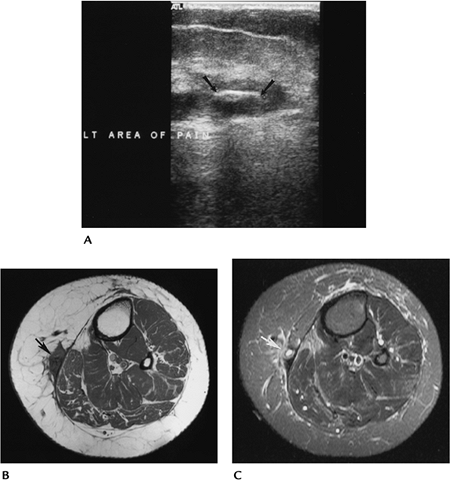

FIGURE 11-10 Foreign body with infection. (A) Ultrasound demonstrates a wooden foreign body (arrows) in the thigh. Axial T1- (B) and contrast-enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted (C) images demonstrate adjacent soft tissue inflammation (arrow).

|

Suggested Reading

Ma LD, Frassica FJ, Bluenke DA, et al. CT and MRI evaluation of musculoskeletal infection. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging 1997;36:535–568.

P.770

Brodie Abscess

Key Facts

-

Brodie abscess is a localized osseous infection usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus. In up to 50% of patients, no organism is identified.

-

Patients often have subtle symptoms and are not systemically ill.

-

Most abscesses are metaphyseal (60%) and

well marginated with surrounding sclerosis, and range from 4 mm to 4 cm

in size. Sequestra are evident in 20%. -

Cortical Brodie abscesses may be confused with osteoid osteoma.

-

The distal tibia is the most common site.

-

MRI or CT is best for diagnosis.

|

|

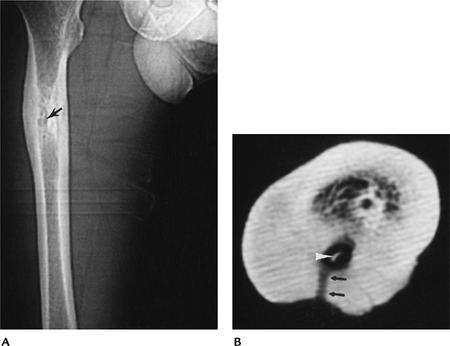

FIGURE 11-11 Brodie abscess. (A) AP radiograph of the femur showing a lucent area (arrow) with cortical thickening and sclerosis. (B) Axial CT image showing a central sequestrum (arrowhead) and sinus tract (cloaca) (arrows) leading through the thickened cortex.

|

P.771

|

|

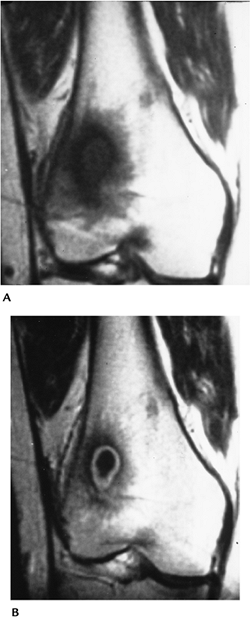

FIGURE 11-12 Brodie abscess. Coronal T1- (A) and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (B) images demonstrate a Brodie abscess in the distal femur with rim enhancement in (B).

|

Suggested Reading

Miller WB, Murphy WA, Gilula LA. Brodie abscess. Reappraisal. Radiology 1979;132:15–23.

P.772

Tuberculosis/Atypical Mycobacterial Infections

Key Facts

-

Musculoskeletal infections from tuberculosis may be from typical (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) strains (3% to 5% involve bone and joints) or atypical (Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonae, Mycobacterium marinum) strains (5% to 10% involve the musculoskeletal system).

-

M. tuberculosis:

Musculoskeletal involvement may occur at any age, but it is rare in

infants. Infections are more common in patients with debilitating

diseases. Fifty percent have pulmonary involvement. The metaphyses and

epiphyses are most often involved. In children, multiple lytic lesions

may mimic fungal infection or neoplasms.-

Radiographic features: Bone involvement

may be difficult to differentiate from pyogenic infection. Joint

infections progress more slowly than pyogenic infections. Joint margin

erosions are more common, and the joint space is preserved for a longer

period compared with pyogenic infections. -

MRI features: Low to intermediate signal

intensity on T2-weighted and low signal intensity on T1-weighted or

higher peripheral signal intensity. Edema pattern and abscesses in 80%.

-

-

Atypical mycobacteria: Atypical mycobacteria are found in soil, water, milk, and animals. Musculoskeletal infections resemble M. tuberculosis,

but the course often is milder. Diagnosis may be delayed up to 10

months from onset of symptoms (fever, chills, malaise, weight loss).-

Radiographic features: Bone involvement is nonspecific. Spine and joint involvement are similar to that found in M. tuberculosis.

Unlike tuberculosis, sinus tracts, sequestra, and periostitis occur

more frequently. Myositis can be found in patients with acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome. Infectious tenosynovitis in the hand and

wrist is common. -

MRI features: nonspecific and similar to tuberculosis. May have rice bodies in soft tissue fluid collections.

-

P.773

|

|

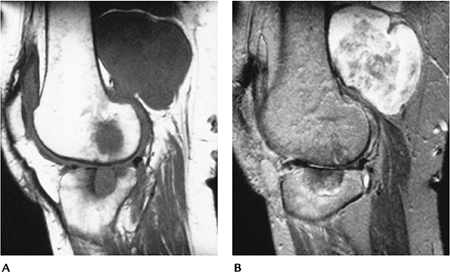

FIGURE 11-13 M. tuberculosis. Sagittal T1-weighted (A) and T2-weighted (B) MR images showing bone erosions and a large inhomogeneous posterior soft tissue abscess.

|

P.774

|

|

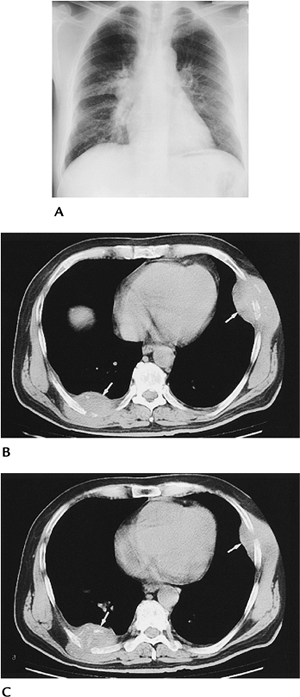

FIGURE 11-14 Tuberculosis with rib destruction and chest wall abscesses. (A) Chest radiograph showing a right perihilar infiltrate and adenopathy. (B,C) CT images showing chest wall abscesses with rib destruction (arrows).

|

P.775

Suggested Reading

Amrami

KK, Sundarum M, Shin AY, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infections of the

distal upper extremity: Clinical course and imaging findings in two

cases with delayed diagnosis. Skel Radiol 2003;32:546–549.

KK, Sundarum M, Shin AY, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infections of the

distal upper extremity: Clinical course and imaging findings in two

cases with delayed diagnosis. Skel Radiol 2003;32:546–549.

Hong SH, Kim SM, Aku JM, et al. Tuberculosis versus pyogenic arthritis. MR imaging evaluation. Radiology 2001;218:848–853.

Theodorou

DJ, Theodorou SJ, Kakitsubata Y, et al. Imaging characteristics and

epidemiologic features of atypical mycobacterial infections involving

the musculoskeletal system. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;176:341–349.

DJ, Theodorou SJ, Kakitsubata Y, et al. Imaging characteristics and

epidemiologic features of atypical mycobacterial infections involving

the musculoskeletal system. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;176:341–349.

P.776

Fungal Infections

Key Facts

-

Fungal infections are most common in

debilitated patients, diabetic patients, patients undergoing steroid

therapy, and patients who reside in specific geographic regions. -

Common fungal infections include

-

Actinomycosis (Actinomyces israelii, Actinomyces bovis)

-

Resides in oral cavity.

-

Bone involvement most common in facial bones.

-

Distal spread can occur via hematogenous route.

-

-

Cryptococcosis (Cryptococcus neoformans)

-

Organism present in soil.

-

Infection via direct implantation in open wound (foot common).

-

Skeletal involvement in 5% to 10%, resulting in destructive bone lesions and draining sinuses.

-

-

Blastomycosis (Blastomyces dermatitidis)

-

Prevalent in Ohio and Mississippi valleys.

-

Infection via skin or inhalation.

-

Skeletal involvement in 50% with pulmonary infection.

-

Radiographic changes include bone destruction and draining sinuses.

-

-

Coccidioidomycosis (Coccidioides immitis)

-

Endemic in southwestern United States.

-

Infection via inhalation.

-

Bone involvement in 10% to 20%.

-

Areas of bony prominence (ligament and tendon attachments) commonly involved.

-

Destructive lesions with aggressive periostitis are common.

-

Bilateral extremity involvement is possible.

-

-

Histoplasmosis (Histoplasma capsulatum, Histoplasma duboisii)

-

Present in soil.

-

Infection via inhalation.

-

More common in children than adults.

-

Bone destruction most common in the axial skeleton.

-

-

Echinococcus (E. granulosis, E. multilocularis, E. vogeli, E. oligarthus)

-

Liver involved in 65%, lung in 15%, musculoskeletal in 1% to 4%.

-

Osseous involvement in the spine in 35%, pelvis in 21%, femora in 10%, tibia in 10%, ribs in 6%.

-

Cystic multilocular lesions that may resemble neoplasms.

-

P.777

|

|

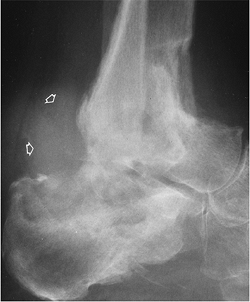

FIGURE 11-15 Coccidioides immitis osteomyelitis. Lateral radiograph of the calcaneus showing marked soft tissue swelling (open arrows) and lytic destruction in the calcaneus, tibia, and fibula.

|

Suggested Reading

Holley K, Muldoon M, Tasker S. Coccidioides immitis osteomyelitis: A case review. Orthopedics 2002;25:827–831.

Rhangos WC, Chick EW. Mycotic infections in the bone. South Med J 1964;57:664–674.