Infections

Authors: Doyle, James R.

Title: Hand and Wrist, 1st Edition

Copyright ©2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Section II – Outpatient Clinic > 5 – Infections

5

Infections

This chapter will present the basic principles involved

in the diagnosis and treatment of common infections in the hand.

Discussion will begin with the more common bacterial infections

involving soft tissue and bone that may be seen in an acute situation.

in the diagnosis and treatment of common infections in the hand.

Discussion will begin with the more common bacterial infections

involving soft tissue and bone that may be seen in an acute situation.

Prior to the antibiotic era, infections in the hand and

their sequelae could be disabling, and in some cases fatal. Antibiotics

have changed that, but early diagnosis and treatment is a necessary

part of the management equation in order to minimize the potential

disability that may result from infections that are diagnosed late or

treated inappropriately. The specifics of the pertinent anatomy as it

relates to each infection will be addressed under each type of

infection.

their sequelae could be disabling, and in some cases fatal. Antibiotics

have changed that, but early diagnosis and treatment is a necessary

part of the management equation in order to minimize the potential

disability that may result from infections that are diagnosed late or

treated inappropriately. The specifics of the pertinent anatomy as it

relates to each infection will be addressed under each type of

infection.

The effect of antibiotics is most pronounced in the

early phases of an infection. Antibiotics may in some instances cure

certain types of infections if they are administered early and are

organism specific. Many infections, however, do not present in a timely

fashion. Some infections may begin as cellulitis; at this stage a more

serious or deep infection may be averted by prompt treatment including

antibiotics, and elevation and rest of the affected part.

early phases of an infection. Antibiotics may in some instances cure

certain types of infections if they are administered early and are

organism specific. Many infections, however, do not present in a timely

fashion. Some infections may begin as cellulitis; at this stage a more

serious or deep infection may be averted by prompt treatment including

antibiotics, and elevation and rest of the affected part.

The patient’s history of injury or onset is often

critical to making the correct diagnosis. Not all patients will be

forthcoming with the true details of the circumstances surrounding the

infection. Human bite wounds are a prime example: most patients will

not admit that the problem occurred from a fistfight, but rather say it

resulted from a fall.

critical to making the correct diagnosis. Not all patients will be

forthcoming with the true details of the circumstances surrounding the

infection. Human bite wounds are a prime example: most patients will

not admit that the problem occurred from a fistfight, but rather say it

resulted from a fall.

A basic principle of the treatment of deep or

closed-space infections is to provide open drainage in a suitable and

timely fashion. Drainage of an infection is accompanied by a culture of

the material obtained, and includes routine bacterial and fungal

cultures. A smear and gram stain of the drained material may allow a

presumptive or tentative identification of the organism involved.

Antibiotics are started based on the most likely organism involved. Table 5-1 includes examples of selected antibiotic agents, and their class, spectrum, use, and cost.

closed-space infections is to provide open drainage in a suitable and

timely fashion. Drainage of an infection is accompanied by a culture of

the material obtained, and includes routine bacterial and fungal

cultures. A smear and gram stain of the drained material may allow a

presumptive or tentative identification of the organism involved.

Antibiotics are started based on the most likely organism involved. Table 5-1 includes examples of selected antibiotic agents, and their class, spectrum, use, and cost.

Immobilizing the affected part and allowing it to rest

are also important aspects of treatment. Elevation means that the

affected part is at least 30 cm above the level of the heart, a posture

that is most easily obtained by recumbency. Sitting in a chair with the hand at or below the level of the heart is not elevation.

Immobilization by use of a splint or cast provides rest to the part and

will also prevent inappropriate inspection or manipulation of the

lesion by the patient.

are also important aspects of treatment. Elevation means that the

affected part is at least 30 cm above the level of the heart, a posture

that is most easily obtained by recumbency. Sitting in a chair with the hand at or below the level of the heart is not elevation.

Immobilization by use of a splint or cast provides rest to the part and

will also prevent inappropriate inspection or manipulation of the

lesion by the patient.

Remember that infections in diabetic, debilitated,

malnourished, or immunocompromised patients will be more difficult to

treat, and will sometimes present as chronic, rather than acute,

infections. Infections in these patients sometimes require amputation

of digits.

malnourished, or immunocompromised patients will be more difficult to

treat, and will sometimes present as chronic, rather than acute,

infections. Infections in these patients sometimes require amputation

of digits.

The following discussion will include some of the more

common infections that may be encountered in the outpatient clinic or

the emergency department.

common infections that may be encountered in the outpatient clinic or

the emergency department.

Felon

The felon is a subcutaneous infection that occurs in the distal pulp of the fingers or thumb.

Pertinent Anatomy

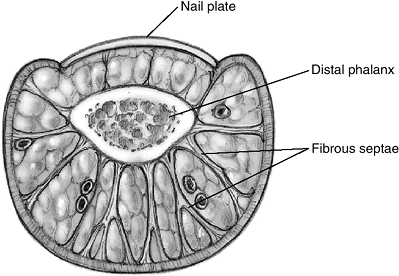

The distal pulp of digits is covered by thick skin that

is tethered to the osseous phalanx by multiple fibrous tissue septae.

This three-dimensional space is filled with fat, and contains numerous

vessels and nerves and their specialized end organs. These septae

stabilize the pulp for pinching and grasping, and form compartments

that may prevent adequate drainage unless incised (Figure 5-1).

is tethered to the osseous phalanx by multiple fibrous tissue septae.

This three-dimensional space is filled with fat, and contains numerous

vessels and nerves and their specialized end organs. These septae

stabilize the pulp for pinching and grasping, and form compartments

that may prevent adequate drainage unless incised (Figure 5-1).

Clinical Appearance and Diagnosis

-

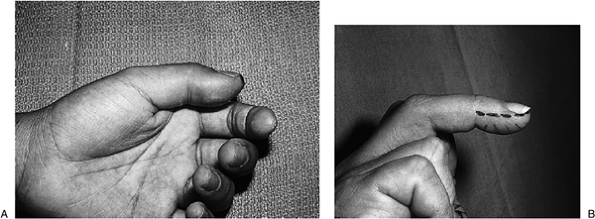

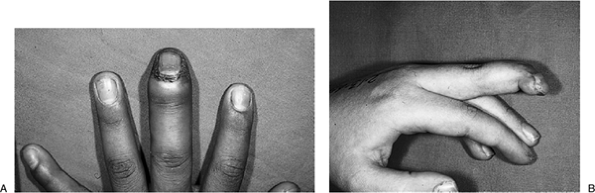

The felon presents as a swollen, red,

painful, and tender terminal phalanx that may or may not have a history

of a penetrating injury (Figure 5-2). -

Spontaneous drainage or pointing of the abscess may occur (Figure 5-3). This indicates a late and neglected infection, and diagnosis and treatment should have been started in a more timely fashion.

-

The felon may also migrate to the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint and to the adjacent flexor sheath in untreated cases.

Treatment

-

Treatment is aimed at decompression of the abscess, which is often under tension.

-

Surgical drainage is indicated if there

is evidence of a purulent collection under pressure. This may occur

within 2 to 3 days of the onset of the condition.P.79P.80 Figure 5-1 The anatomy of the terminal phalanx.

Figure 5-1 The anatomy of the terminal phalanx.![]() Figure 5-2 (A) Clinical appearance (swelling) of a felon in the thumb. The pulp was firm and tender to palpation. (B)

Figure 5-2 (A) Clinical appearance (swelling) of a felon in the thumb. The pulp was firm and tender to palpation. (B)

Felon of the left middle finger. Note the swelling in the pulp and the

proposed midlateral incision of the noncontact side of the digit. -

The aim of surgery is to produce immediate and continuous drainage of the abscess.

-

The usual organism is Staphylococcus aureus, although opportunistic gram-negative and mixed organisms may be encountered in the immuno-compromised patient.

-

This requires an appropriate incision and division of the fibrous septae to promote drainage.

-

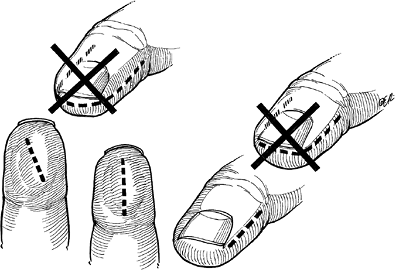

Appropriate and inappropriate incisions for drainage of the felon are depicted in Figure 5-4.

-

Incisions that extend on both sides of

the pulp (fish-mouth incisions) are to be avoided. They result in

unsuitable scars, may result in vascular or neurological compromise of

the resultant flap, and in general alter the shape and function of the

pulp. -

The preferred surgical incision is a

lateral midaxial incision that begins distal to the DIP joint flexion

crease and continues distally at a level adjacent to the free edge of

the nail plate.P.81 Figure 5-3 A felon that was neglected and drained spontaneously (or pointed).

Figure 5-3 A felon that was neglected and drained spontaneously (or pointed).-

This incision maintains the architectural

integrity of the pulp, while at the same time providing adequate

exposure and drainage.

-

-

Oblique or longitudinal volar incisions

may be used if the abscess is pointing in that direction (volar), but

should be relatively short and should avoid injuring the underlying

digital nerves.-

This volar incision may be most suitable when the abscess has spontaneously drained in that direction.

-

These incisions should not cross the flexion crease.

-

-

The incisions are placed on the non-contact side of the digit.

-

In the index, middle, and ring fingers,

the incisions are on the ulnar side and in the thumb and little finger

they are on the radial side.

-

Drains, Antibiotic Therapy and Splints

-

A small drain is inserted into the wound to keep it open and promote drainage.

![]() Figure 5-4 Inappropriate (marked with an X) and appropriate incisions for drainage of the felon.

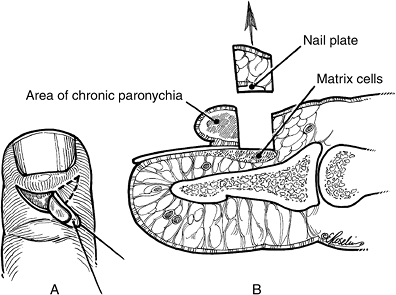

Figure 5-4 Inappropriate (marked with an X) and appropriate incisions for drainage of the felon. Figure 5-5

Figure 5-5

The anatomy of the distal phalanx showing the finger nail components,

nail plate, matrix, and eponychium, with an artist’s depiction of a

lateral fold infection called a paronychia.-

An alternative to this drain is to place a small catheter in the wound for irrigation and drainage.

-

-

Antibiotic therapy, along with rest (a plaster splint is effective) and elevation of the extremity, is instituted.

-

Prompt drainage, suitable incisions, and

antibiotic therapy usually result in a satisfactory outcome that will

preserve the function of the pulp and avoid a disabling scar. These

actions also tend to prevent the spread of the infection to bone or to

the flexor tendon sheath.

Acute Paronychia

Pertinent Anatomy

A paronychia is an infection of the lateral soft tissue

fold surrounding the nail plate. The interface between the nail plate

and the overlying skin is a unique anatomic arrangement that allows for

growth of the nail plate from matrix cells (Figure 5-5).

This interface or seal however may be penetrated by foreign bodies that

introduce bacteria into an otherwise sterile interface. Over-vigorous

manicures and nail biting may be associated with these infections.

fold surrounding the nail plate. The interface between the nail plate

and the overlying skin is a unique anatomic arrangement that allows for

growth of the nail plate from matrix cells (Figure 5-5).

This interface or seal however may be penetrated by foreign bodies that

introduce bacteria into an otherwise sterile interface. Over-vigorous

manicures and nail biting may be associated with these infections.

Clinical Appearance and Diagnosis

-

The initial infection usually involves half or less of the eponychia fold, and in such instances is called an eponychia.

-

A neglected infection may involve the entire fold, and is called a run-around infection (Figure 5-6A).

-

These neglected lesions may spread to the

insertion of the adjacent extensor tendon. This can result in a mallet

finger deformity and can deform the fingernail secondary to injury to

the germinal nail matrix (Figure 5-6B). -

Staphylococcus aureus is the usual organism involved, but Streptococcus and oral anaerobes may be seen in infections caused by nail biting.

P.82

|

|

Figure 5-6 (A) The “run-around” form of paronychia. (B) The end result of delayed treatment of a severe paronychium with chronic mallet finger and nail deformity.

|

Treatment

-

Early cases (before fluctuance and an abscess have developed) may be treated by warm water soaks, splinting, and cephalosporins.

-

If an abscess is identified, it must be

drained by one of several methods, including elevation of the

eponychial fold to drain the purulent material, followed by insertion

of a small drain; or an oblique incision in the eponychial fold

centered over the site of maximum involvement. In more chronic cases, a

margin of the nail plate is removed, followed by a drain insertion.

Chronic Paronychia

Clinical Appearance and Diagnosis

-

The term chronic paronychia is used to describe nonbacterial infection of the eponychial fold caused, most commonly, by a Candida albicans

infection. Other organisms such as tuberculosis, syphilis, atypical

mycobacteria, gram-negative rods, and cocci have also been identified,

however. -

It is most often associated with chronic

maceration, and occurs in patients such as dishwashers, homemakers,

bartenders, and others that have their hands in water that contain

irritants. -

Some have concluded that this condition is a type of hand dermatitis and not onychomycosis.

Treatment

-

Treatment is difficult and not always successful.

-

Nonsurgical treatment includes topical corticosteroids and systemic antifungal agents.

-

Treatment that removes the patient from constant exposure to water may be as important as medications.

-

In patients who do not respond to conservative treatment, surgical marsupialization with or without plate removal may be effective.

-

A crescent of skin that is 3 to 4 mm wide

is excised proximal and parallel to the eponychium, which includes

skin, fat, and nail plate—but not the nail matrix (Figure 5-7).

Herpes Simplex (Herpetic Whitlow)

Clinical Appearance and Diagnosis

-

This condition represents an important differential diagnosis of both pyogenic paronychia and felon.

-

It is an infection caused by the herpes simplex virus (types 1 or 2) and is usually seen in medical and dental personnel.

-

The affected digit is swollen, painful, and red.

-

The infection may involve more than one digit and is often less tender than a bacterial lesion.

-

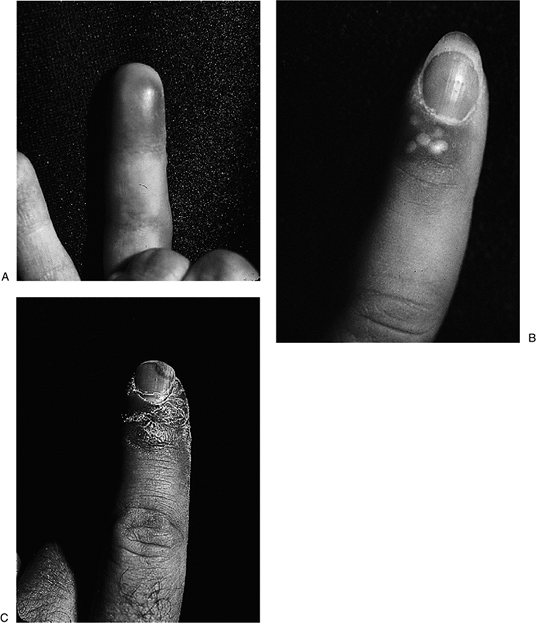

Figure 5-8 shows the typical appearance of the herpes simplex lesion in the digit.

-

Small vesicles may appear early on, and the fluid in them is clear and not purulent.

-

These lesions then involute and desquamate, and the cycle resolves in 3 to 4 weeks.

-

The diagnosis is usually made by taking a history and performing an examination.

-

|

|

Figure 5-7 Marsupialization technique for surgical management of chronic paronychia.

|

P.83

|

|

Figure 5-8 The clinical appearance of a herpes simplex infection in the digit. (A) The erythematous phase. (B) The pustular phase. (C) The desquamation phase. (Courtesy of Dean S. Louis, University of Michigan.)

|

Treatment

-

Surgery is not necessary and is contraindicated

since bacterial infections may contaminate the incision site. Systemic

dissemination with a secondary viral encephalitis can also occur.

Pyogenic Flexor Tenosynovitis

Pertinent Anatomy

The flexor tendons are enclosed in a double-walled

synovial sheath that extends from the region of the DIP joint to the

midpalm in the index, middle, and ring fingers; from the DIP joint to

the wrist in the little finger; and from the interphalangeal (IP) joint

to the wrist in the thumb. The most common arrangement of the synovial

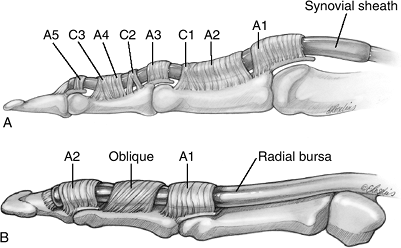

sheath of the digits is shown in Figure 5-9.

This sheath represents a closed space that, if infected, can produce

severe disability in the digit. Such infections require early diagnosis

and appropriate treatment. The relationship of the pulley system that

must be preserved during surgical drainage is depicted in Figure 5-10.

synovial sheath that extends from the region of the DIP joint to the

midpalm in the index, middle, and ring fingers; from the DIP joint to

the wrist in the little finger; and from the interphalangeal (IP) joint

to the wrist in the thumb. The most common arrangement of the synovial

sheath of the digits is shown in Figure 5-9.

This sheath represents a closed space that, if infected, can produce

severe disability in the digit. Such infections require early diagnosis

and appropriate treatment. The relationship of the pulley system that

must be preserved during surgical drainage is depicted in Figure 5-10.

Clinical Appearance and Diagnosis

-

Kanavel described four characteristic findings in pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis:

-

Flexed posture of the finger.

-

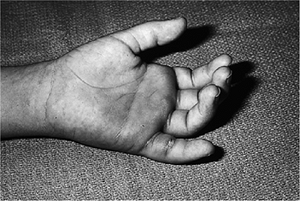

Swelling of the finger (Figure 5-11).

-

Tenderness along the course of the sheath.

-

Significant pain with passive extension of the flexed finger.

-

-

The most common organism is Staphylococcus aureus.

P.84

|

|

Figure 5-9

The most common arrangement of the synovial sheaths in the hand. This configuration gives anatomic support to the concept of the “horseshoe abscess,” which is a flexor sheath synovial infection that may communicate from thumb to little finger and vice versa through Parona’s space. See Figure 5-12 for depiction of Parona’s space. |

|

|

Figure 5-10 The digital pulley system. (A) The finger pulleys. (B) The thumb pulleys.

|

|

|

Figure 5-11

The clinical appearance of pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis in the little finger following an untreated laceration at the PIP flexion crease. Note the swelling and erythema in the finger and palm. |

Treatment

-

If seen early (within 24 to 48 hours), it

may be feasible to treat to the condition by hospitalization with

intravenous antibiotics, bed rest and elevation of the hand, and

immobilization with a splint—with the hand and wrist in the position of

function (wrist in moderate extension and the fingers slightly flexed).-

The patient should be evaluated twice

daily; if the condition is not resolved within 24 to 48 hours, surgical

drainage should be performed.

-

-

Most cases will be in the late category.

Surgical drainage is performed along with the modalities listed for

early conservative treatment. -

Open drainage through midaxial and palmar

incisions has been employed in the past for these infections, but when

compared to closed catheter irrigation, the former technique may be

associated with a higher incidence of complication and reoperation. -

The current trend for recommended treatment is for closed catheter irrigation.

-

Closed catheter irrigation consists of

insertion of a 16-gauge polyethylene catheter into the sheath just

proximal to the first annular pulley through a transverse, oblique, or

zigzag incision. -

The catheter is passed under the A1 pulley distally for about 2 cm (see Figure 5-10).

-

The catheter is sutured to the skin, and the wound is closed.

-

A second incision is made distally,

either on the noncontact side of the digit in the midaxial plane or

volarly distal to the A4 pulley. -

The sheath distal to the A4 pulley is excised, and a small drain is sutured in place to ensure that the distal wound stays open.

-

The patency and drainage of the construct is tested by the injection of sterile saline through the proximally placed catheter.

-

A variation on this technique is to bring

the distal end of the catheter out the distal wound and allow passage

of saline in the sheath by two to three openings made in the catheter

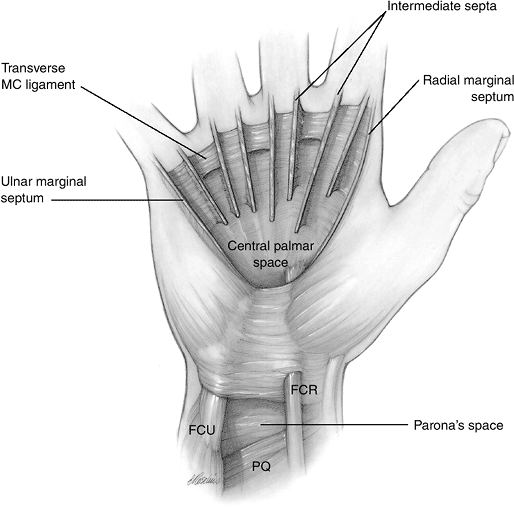

within the sheath.P.85![]() Figure 5-12 The palmar space and Parona’s space (see text for details).

Figure 5-12 The palmar space and Parona’s space (see text for details).-

The proximal portion of the catheter is brought out through the dressings, and attached to a sterile 50-mL syringe.

-

The distal wound is left exposed in the splint and dressings for visual verification of patency of the system.

-

-

The system is flushed with sterile saline

every 2 hours for 48 hours, and then the finger is inspected.

Comparable end results might be achieved without postoperative

irrigation. -

If the infection has abated, the catheter should be removed and gentle range of motion exercises should begin.

-

If there is some question about the status of the infection, the irrigation can be continued for another 24 hours.

-

General principles in this technique

include preservation of the annular pulleys during placement of the

catheter, and concomitant intravenous antibiotic therapy.

Central Palmar Space Infections

Pertinent Anatomy

I recommend that the following concept regarding the

palmar space, based on the work of Bojsen-Moeller and Schmidt, be

accepted as valid.

palmar space, based on the work of Bojsen-Moeller and Schmidt, be

accepted as valid.

-

The central palmar space is bounded radially and ulnarly by marginal septae that begin as an expansion of the sidewalls of the carpal canal.

-

The floor is formed by the palmar interosseous fascia, transverse metacarpal ligaments, and adductor fascia.

-

The roof is formed by the palmar aponeurosis.

-

The radial marginal septum extends

distally to the proximal phalanx of the index finger, and forms the

radial wall of the lumbrical canal. -

The ulnar margin septum is attached to the shaft of the small finger metacarpal.

-

Between these two marginal septae are

seven intermediate septae that divide the distal aspect of the central

palmar space into four canals for the flexor tendons and four canals to

accommodate the lumbrical muscle and neurovascular bundles. -

Thus, the historical

concepts of a thenar and midpalmar or, as later modified, an adductor

and deep palmar ulnar space should be abandoned in my opinion (Figure 5-12).

Clinical Appearance and Diagnosis

-

An infection of the central palmar space

may result from a penetrating injury to the space or an extension of an

infected digital synovial sheath. -

There may be swelling, redness, and

tenderness in the central aspect of the palm, and active and passive

movement of the fingers may be painful.

Treatment

-

Surgical drainage may be performed

through an incision in or parallel to the proximal palmar crease or

thenar crease to correspond to the site of maximum fluctuance. -

A drain is placed to promote continuous egress, and a splint is applied.

-

Elevation of the extremity, bed rest, and appropriate antibiotics complete the treatment regimen.

P.86

Special Situations

Several conditions may present as unique situations and may seem somewhat out of the ordinary.

Horseshoe Abscess

-

This term is used to describe an

infection that may begin in the thumb or little finger flexor sheath

and that may infect the opposing digit. -

This occurs when sufficient pressure in

the respective sheath results in passage of the infected material into

Parona’s space in the wrist and then into the opposing tendon sheath.

(see Figure 5-9 and Figure 5-12) -

The treatment principles described for

flexor tenosynovitis are used, and drainage is required for both of the

digits involved and at the wrist (Parona’s space).

Collar Button Abscess

-

This term has been used to describe interdigital web-space infections.

-

The infections usually begin in the palm.

-

The palmar fascia attachments to the skin

provide resistance to superficial palmar spread, and the infection will

spread dorsally in the path of least resistance. Thus, the lesion

presents in the shape of a collar button or an hourglass. -

Patients present with painful swelling in the web space and distal palm.

-

Palmar and dorsal drainage is effective

treatment through appropriate incisions such as a zigzag palmar

incision and a longitudinal web incision dorsally.

Osteomyelitis

Although osteomyelitis may be seen in the hand by direct

extension from an adjacent soft tissue infection, it may also result

from direct penetration. It seldom occurs by the hematogenous route. Staphylococcus aureus and S. epidermidis are the usual organisms involved.

extension from an adjacent soft tissue infection, it may also result

from direct penetration. It seldom occurs by the hematogenous route. Staphylococcus aureus and S. epidermidis are the usual organisms involved.

Clinical Appearance and Diagnosis

-

Osteomyelitis should be suspected in any

longstanding or deep infection that is adjacent to bone, or in an

infection following a deep, penetrating wound. -

Chronic swelling and infections that fail to resolve with standard treatment may indicate osteomyelitis.

-

Elevation, increased thickness of the

periosteum, or an osteolytic lesion in the bone, seen on radiograph,

are signs of bone infection. -

A foreign body with an osteolytic halo is also suggestive of osteomyelitis.

-

C-reactive protein may be elevated.

-

A technetium bone scan may be diagnostic.

|

|

Figure 5-13

This neglected glass laceration resulted in a chronic infection of the middle finger involving soft tissues, bone, and joint. The problem could not be resolved with elevation, rest to the part, and antibiotics. An amputation was performed with resolution of the infection. |

Treatment

-

Drainage of the bone is indicated through drill holes in the cortex or a small window.

-

Necrotic bone (sequestrum) is removed if it is present.

-

The wound may be packed open, or the catheter irrigation method may be used.

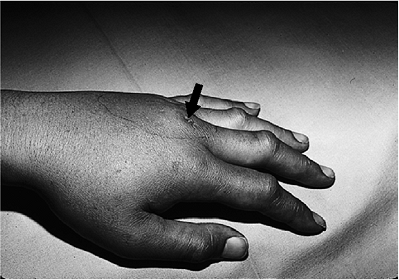

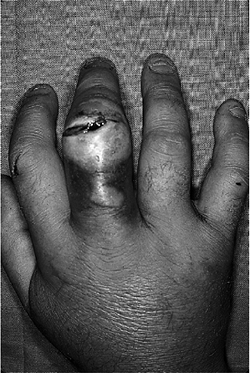

![]() Figure 5-14 Human bite wound. This policeman sustained a penetrating tooth wound (arrow)

Figure 5-14 Human bite wound. This policeman sustained a penetrating tooth wound (arrow)

to the MCP joint of the left middle finger, and shortly thereafter

noted pain and swelling in the hand. Incision and drainage was

required, along with hospitalization and intravenous antibiotics.P.87 Figure 5-15

Figure 5-15

This cat owner sustained multiple scratches and bites to the dorsum of

her hand that resulted in cellulitis, with swelling, redness, and pain.

The infection developed overnight. The organism was Pasteurella multocida, and the condition quickly resolved with intravenous penicillin. -

In some cases with severe bone and soft tissue involvement, amputation may be the best treatment (Figure 5-13).

Human Bite Wounds

These wounds are most often seen over the

metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint and are due to a fist blow to an

opponent’s mouth. The history of injury is not often forthcoming due to

embarrassment.

metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint and are due to a fist blow to an

opponent’s mouth. The history of injury is not often forthcoming due to

embarrassment.

Clinical Appearance and Diagnosis

-

These wounds are often small and may initially appear very benign.

-

The opponent’s tooth penetrates the MCP joint space and inoculates this closed space with a variety of organisms, including Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus viridans, and Eikenella corrodens.

-

Later on there is swelling, redness, and increasing pain (Figure 5-14).

-

A radiograph of the injured hand may reveal a fracture or a piece of the opponent’s tooth in the joint.

Treatment

-

These injuries should never be closed primarily.

-

They should be opened and debrided

extensively. This includes excision of the initial wound margins and

extension of the wound to allow proper exposure, inspection, and

irrigation of the joint involved. -

The wound is cultured prior to irrigation and debridement.

-

It is left open and the hand is dressed and splinted.

-

Appropriate antibiotics are started after cultures have been obtained.

-

Patients with bite wounds from humans may

not always keep their follow-up appointments, and serious consideration

should be given to hospitalization until the condition is resolved.

Animal Bites

Clinical Appearance and Diagnosis

-

Domestic animal bites or scratches may result in the rapid onset of cellulitis and lymphangitis.

-

The most commonly isolated organisms from dog and cat bites are Streptococcus viridans, Pasteurella multocida, S. aureus, and anaerobes.

-

Figure 5-15 represents a case of P. multocida (a small gram-negative coccus) cellulitis following a bite from the patient’s house cat.

-

The condition must be distinguished from cat scratch disease

or fever, which is usually associated with small red lesions on the

hand or wrist, lymphadenopathy, and a history of cat scratch. The

organism is Rochalimaea henselae, a gram-negative bacillus. -

A skin test may be confirmatory.

Treatment

-

Penicillin is the antibiotic of choice for animal bites.

-

The treatment for cat scratch disease is said to be controversial because it is a self-limiting disease.

-

Ciprofloxacin has been used.

Suggested Reading

Bojsen-Moeller F, Schmidt L. The palmar aponeurosis and the central spaces of the hand. J Anat 1974;117:55–68.

Cornwall

R, Bednar MS. Infections. In: Trumble TE, ed. Hand surgery update-3,

hand, elbow & shoulder. Rosemont, IL: American Society for Surgery

of the Hand, 2003:433–457.

R, Bednar MS. Infections. In: Trumble TE, ed. Hand surgery update-3,

hand, elbow & shoulder. Rosemont, IL: American Society for Surgery

of the Hand, 2003:433–457.

Jebson PJL, Louis DS, eds. Hand infections. Hand Clinics 1998;14(4):511–711.

Neviaser

RL. Acute infections. In: Green DP, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, eds.

Green’s operative hand surgery. 4th Ed. New York: Churchhill

Livingstone, 1999:1033–1047.

RL. Acute infections. In: Green DP, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, eds.

Green’s operative hand surgery. 4th Ed. New York: Churchhill

Livingstone, 1999:1033–1047.

Tosti

A, Piraccini BM, Ghetti E, Colombo MD. Topical steroids versus systemic

antifungals in the treatment of chronic paronychia: an open, randomized

double-blind study and double dummy study. J Am Acad Dermatol

2002;47:73–76.

A, Piraccini BM, Ghetti E, Colombo MD. Topical steroids versus systemic

antifungals in the treatment of chronic paronychia: an open, randomized

double-blind study and double dummy study. J Am Acad Dermatol

2002;47:73–76.

Wright

PE II. Hand infections. In: Canale ST, Dougherty K, Jones L, eds.

Campbell’s operative orthopedics. vol. IV, 10th Ed. Philadelphia:

Mosby, 2003:3809–3825.

PE II. Hand infections. In: Canale ST, Dougherty K, Jones L, eds.

Campbell’s operative orthopedics. vol. IV, 10th Ed. Philadelphia:

Mosby, 2003:3809–3825.