HIP Dislocations, Femoral Head Fractures, and Acetabular Fractures

fracture, is a major injury. The forces needed to cause hip dislocation

are considerable, and, in addition to the disruption noted on

roentgenography, soft-tissue injury is significant. Occasionally, small

osseous or cartilaginous fragments remain in the hip joint. The injury

is most frequently caused by an automobile or automobile-pedestrian

accident, so significant injury elsewhere in the body is likely. A

fracture or fracture-dislocation at the hip can easily be missed when

associated with an ipsilateral extremity injury. Such an injury

emphasizes the rule: always visualize the joint above and the joint

below the diaphyseal fracture. Because injuries about the pelvis can be

missed in a seriously traumatized patient, most authorities advocate a

routine pelvic roentgenogram for all patients involved in severe blunt

trauma. The condition is viewed as an orthopaedic emergency. In

general, the sooner the reduction is achieved, the better is the end

result (1,2).

-

Anterior dislocations

-

Obturator

-

Iliac

-

Pubic

-

Associated femoral head fractures (see V)

-

-

Posterior dislocations

-

Without fracture

-

With posterior wall fracture (see IV)

-

With femoral head fracture (see V)

-

-

This injury usually occurs in an automobile accident, in a severe fall, or from a blow to the back while squatting. The mechanism of injury

is forced abduction. The neck of the femur or trochanter impinges on

the rim of the acetabulum and levers the femoral head out through a

tear in the anterior capsule. If in relative extension, an iliac or

pubic dislocation occurs; if the hip is in flexion, an obturator

dislocation occurs. In many instances, there is an associated impaction

or shear fracture of the femoral head as the head passes superiorly

over the anteroinferior rim of the acetabulum. These injuries are

associated with poor long-term results (3,4). -

On examination with an obturator dislocation, the hip is abducted, externally rotated, and flexed, but in the iliac or pubic dislocation,

the hip may be extended. The femoral head can usually be palpated near

the anterior iliac spine in an iliac dislocation or in the groin in a

pubic dislocation. In all patients, carefully assess the circulatory

and neurologic status before attempting a reduction. The diagnosis is

readily apparent on roentgenogram, which shows the femoral head out of

the acetabulum in an inferior and medial position. -

Treatment (2,3).

Early closed reduction is the treatment of choice, but open reduction

may be necessary. Reduction is optimally attempted under spinal or

general anesthesia, which ensures complete muscle relaxation. In the

multiply injured patient, reduction may be attempted in the emergency

department with sedation or pharmacologic paralysis after the airway is

controlled. Initiate strong but gentle traction along the axis of the

femur while an assistant applies stabilization of the pelvis by

pressure on the anterior iliac crests. For the obturator dislocation, the

P.308

traction is continued while the hip is gently flexed, and the reduction

is accomplished usually by gentle internal rotation. A final maneuver

of adduction completes the reduction but should not be attempted until

the head has cleared the rim of the acetabulum with traction in the

flexed position. For the iliac or pubic dislocation,

the head should be pulled distal to the acetabulum. The hip is gently

flexed and internally rotated. No adduction is necessary. If the hip

does not reduce easily, forceful attempts are not indicated. Failure to

obtain easy reduction with the above maneuvers usually indicates that

traction is increasing the tension on the iliopsoas or closing a rent

in the anterior capsule, producing a “buttonhole” effect. Forced

maneuvers only increase the damage. Because the closed reduction may

fail, the patient is initially prepared for an open procedure. The open

reduction can be accomplished through a muscle-splitting incision,

using the lower portion of the standard anterior Smith-Peterson

approach. The structures preventing the reduction are released. The

postreduction treatment is the same as for a posterior dislocation of

the hip, except it is important to avoid excessive abduction and

external rotation. -

Prognosis and complications.

Excellent reviews of hip dislocations have been published; anterior

dislocations occur in approximately 13% of some 1,000 hip dislocations.

Early reduction is necessary if a satisfactory result is to be

obtained, and although the end result is frequently excellent in the

child, traumatic arthrosis and, occasionally, avascular necrosis make

the prognosis guarded in the adult. Recurrent dislocation is rare in an

adult (1,2,3).

-

The mechanism of injury

is usually a force applied against the flexed knee with the hip in

flexion, as occurs most commonly when the knee strikes the dashboard of

an automobile during a head-on impact. If the hip is in neutral or

adduction at the time of impact, a simple dislocation is likely, but if

the hip is in slight abduction, an associated fracture of the posterior

or posterosuperior acetabulum can result. As the degree of hip flexion

increases, it is more probable that a simple dislocation is produced. -

Physical examination

reveals that the leg is shortened, internally rotated, and adducted. A

careful physical examination should be carried out before reduction

including sensory exam and muscle group motor strength grading. Sciatic

nerve injury is associated with 10% to 13% of these injuries (5).

Associated bony or ligamentous injury to the ipsilateral knee, femoral

head, or femoral shaft is not uncommon. When associated with a femoral

shaft fracture, a dislocation may go unrecognized because the classic

position of flexion, internal rotation, and adduction is not apparent.

In this situation, the diagnosis is confirmed by a single

anteroposterior roentgenogram of the pelvis as part of the initial

trauma roentgenographic series. This single examination does not allow

adequate assessment of any associated acetabular fracture (6,7,8),

however, so more roentgenograms are needed for treatment planning

before carrying out a reduction if an acetabular fracture is

identified. The patient, not the x-ray beam, is moved to obtain the

following films: the anteroposterior obturator oblique and the iliac

oblique views (6,9).

This is best accomplished by keeping the patient on a backboard and

using foam blocks to support the oblique position of the board (Fig. 22-1).

If necessary, computed tomography (CT) scanning can also be performed;

optimally, this is done after the closed reduction of the hip joint to

reestablish femoral head circulation. Although some authors question

its routine use after uneventful closed reduction, others report a 50%

incidence of bony fragments being identified with CT (9,10,11,12). -

Treatment

-

Posterior dislocation without fracture.

This dislocation is reduced as soon as possible and always within 8 to

12 hours when possible. Reduction is accomplished with the Allis

maneuver under spinal or general anesthesia to overcome the significant

muscle spasm. The essential step in a reduction is traction in the line

of the deformity, followed by gentle flexion of the hip to 90 degrees

while an assistant stabilizes the pelvis with pressure on the iliac

spine. With continued traction, the hip then is gently rotated into

internal

P.309

and

external rotation, which usually brings about a prompt restoration of

position. Because considerable traction is required, even with good

muscle relaxation, the alternative method of Stimson may be attempted.

The patient is placed prone with the hip flexed over the end of the

table, and an assistant fixes the pelvis by extending the opposite leg.

The same traction maneuvers described earlier are completed, but the

pull is toward the floor with pressure behind the flexed knee. Although

considerable traction is necessary, under no circumstances should rough

or sudden manipulative movement be attempted. Postreduction stability

should be confirmed on physical examination and by a roentgenogram

obtained in the operating room to be sure there are no fractures around

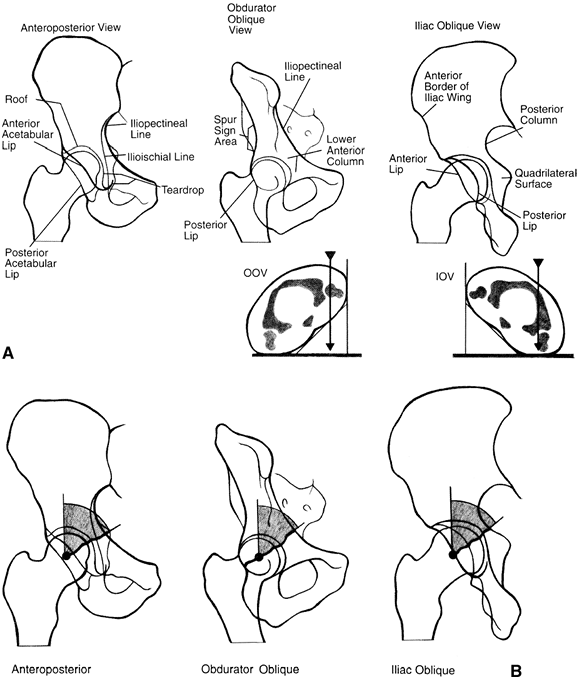

the femoral head or neck. Figure 22-1. Radiographic assessment of acetabular fractures. A: The anteroposterior, obturator oblique, and iliac views are essential for the definition of the fracture. B:

Figure 22-1. Radiographic assessment of acetabular fractures. A: The anteroposterior, obturator oblique, and iliac views are essential for the definition of the fracture. B:

The “roof arc” measurement is made between a vertical line and the

angle of the fracture. Angles greater than 40 degrees on all three

views indicate a fracture which may be treated nonoperatively. (From

Hansen ST, Swiontkowski MF. Orthopaedic trauma protocols. New York: Raven, 1993:249.)P.310-

Postreduction treatment.

Isometric exercises for the hip musculature are instituted as soon as

pain subsides sufficiently. Continuous passive motion (CPM) may be

useful to maintain joint motion but is not essential. There is no

consensus in the literature as to the length of time the patient should

be restricted from weight bearing. The authors favor bed rest until the

patient is pain free and has established near-normal abduction and

extension muscle power. The patient then is allowed to move around,

using crutches for protective weight bearing until it is determined

that he or she can ambulate without pain or an antalgic limp; this

generally takes 3 to 6 weeks. At that time, full weight bearing is

permitted. -

Prognosis and complications

-

Sciatic nerve injuries are discussed in IV.2.c and e.

-

Avascular necrosis of the femoral head

is the most feared delayed complication from a simple posterior

dislocation of the hip. It occurs late, but various authors have noted

an average time of 17 to 24 months from injury to time of diagnosis.

Rates of approximately 6% to 27% are variously reported, and figures

show an incidence of 15.5% for early closed reductions, increasing to

48% if reduction is delayed. There were no good results if reduction

was delayed more than 48 hours. In Epstein’s classic study of 426

cases, better results were obtained with open reduction and internal

fixation in patients who had associated fractures (see Selected Historical Readings).

The overall rate of avascular necrosis was 13.4% with a higher rate of

18% in patients with associated fractures. For fracture-dislocations

treated by open means, the avascular necrosis rate was only 5.5%.

Treatment of avascular necrosis is discussed in Chap. 23, I.I.2. -

Epstein also reported an overall rate of traumatic osteoarthritis

of 23% following posterior hip dislocations, with a rate of 35% in

dislocations treated by closed means and a rate of 17% in those treated

by open means. In another series, after 12 to 14 years of follow-up,

16% of patients had posttraumatic arthritis, and arthritis developed in

an additional 8% as a result of avascular necrosis (2). Similar results have been reported from other centers (1,2).

-

-

-

Posterior dislocation with associated acetabular fracture

-

As previously noted, the dislocation is reduced as soon as possible considering the patient’s other injuries.

If the patient needs to undergo a lengthy trauma evaluation, then an

attempt can be made in the emergency department to reduce the hip with

sedation. In the patient who has been intubated for airway control,

chemical paralysis totally eliminates muscle spasm. If reduction

attempts fail, then the urgency for hip reduction must be transmitted

to the trauma team leader so the patient can be brought to the

operating room earlier in the evaluation phase. An alternative to

standard closed reduction maneuvers involves inserting a 5-mm Schanz

pin into the ipsilateral proximal femur at the level of the lesser

trochanter. This allows more focused lateral and distal traction by a

second assistant to accompany the reduction maneuver. If this maneuver

fails, then open reduction is preferred via a posterior approach. A

posterior wall fracture is internally fixed with lag screws and a

neutralization plate after joint lavage. If a more complex acetabular

fracture is present, then an experienced acetabular and pelvic surgeon

should be consulted (13). If the basic

posterior acetabular anatomy appears intact and the joint debridement

is complete, then a CT scan should be obtained to check on the adequacy

of debridement and to evaluate for associated fractures (4,11). -

Postoperative treatment.

Historically, traction has been used postoperatively, but this is no

longer recommended. With stable internal fixation, early motion is

advised starting with CPM. Flexion is generally limited to 60 degrees

for the first 6 weeks postoperatively for large posterior wall

fractures (13). Weight bearing is limited and crutches are used for 12 weeks (6,7,8,9). -

Sciatic nerve injury.

Direct contusion, partial laceration by bone fragments, a traction

injury, or occasionally an iatrogenic injury resulting from

malplacement of retractors during open reduction can cause this injury.

Nerve injury should be evaluated early by a careful motor and sensory

examination before reduction. If the nerve function is normal before

reduction and is abnormal after reduction, then this may represent

sciatic nerve entrapment in a fracture line. Emergent open reduction

and nerve exploration are indicated (6,7,8,9).

The peroneal portion of the sciatic nerve is most commonly injured

because it lies against the bone in the sciatic notch. When the entire

distal sciatic nerve function is abnormal, the tibial portion of

function returns nearly 100% of the time. The peroneal portion of

function is regained in 60% to 70% of cases: The more dense the motor

injury, the less likely is the return of good function (5).

The postinjury foot drop is generally easily managed by a plastic

ankle-foot orthotic. Tendon transfers at a later date remain an option. -

Prognosis and complications. Late traumatic arthritis and femoral head avascular necrosis can result in 20% to 30% of cases (6,7,8,9,13).

Of all acetabular fractures, the posterior wall injury, despite its

being the simplest pattern, has the worst prognosis with regard to

these complications (14,15,16).

Total hip arthroplasty is the most acceptable reconstruction option

when these complications occur; long-term results in this situation are

not as predictable as with total hip arthroplasty for arthritis (2,15).

Rarely total hip arthroplasty is indicated as the initial surgical

therapy in elderly patients with complex fracture patterns (17).

Most patients who sustain these injuries are younger than 50 years of

age, so loosening of the components over the patient’s lifetime is a

real concern (16).

P.311 -

-

-

Diagnosis.

Fractures of the femoral head generally occur with an associated hip

dislocation. They are seen as abrasion or indentation fractures of the

superior aspect of the head in association with an anterior dislocation

or as shear fractures of the inferior aspect of the head in association

with a posterior dislocation. Comminuted head fractures occasionally

occur with severe trauma. Femoral neck or acetabular fractures may be

involved. The diagnosis is established by roentgenograms and CT scan. -

Treatment

-

Emergent.

Early treatment must focus on reducing the hip dislocation and

diagnosing the fracture pattern. Diagnosis, made by clinical

examination, is confirmed by the admission anteroposterior pelvic

roentgenogram. Great care should be given in evaluating the

roentgenograms before reducing the hip because nondisplaced associated

femoral neck fractures may be displaced with the reduction maneuver. If

these are noted, the reduction should be performed in the operating

room under fluoroscopy so that, if the femoral neck fracture appears

unstable with the reduction maneuver, the surgeon can proceed with an

open reduction. If the closed reduction is successful, a repeat

roentgenogram is obtained to confirm the reduction and a CT scan should

be obtained for treatment planning. -

Definitive.

If the femoral head fracture is an indentation fracture associated with

an anterior dislocation, early CPM and mobilization with crutches

(partial weight bearing) are indicated. The prognosis regarding

degenerative joint disease is poor, however (3,4,18).-

If the femoral head fracture is a shear fracture associated with a posterior dislocation and is of small size (Pipkin type I, infrafoveal),

the treatment can involve a brief period of traction for comfort

followed by mobilization with a restriction of flexion to less than 60

degrees for 6 weeks. Indications for surgery include a restriction of

hip motion resulting from an incarcerated fragment and multiple

associated injuries. The fracture should be approached anteriorly for

best visualization (18). -

If the fracture is of larger size (Pipkin type II, suprafoveal),

the reduction should be anatomic or within 1 mm on the postreduction CT

to proceed with conservative treatment as outlined earlier. If it is

displaced,

P.312

open reduction and internal fixation with well-recessed (countersink) screws using an anterior approach is indicated (18). -

If the fracture is associated with a femoral neck fracture (Pipkin type III),

both fractures should be internally fixed via an anterior approach, and

early motion with CPM should be initiated. The prognosis for this

combination injury is not as favorable as with isolated femoral head

fractures because of the higher incidence of posttraumatic

osteonecrosis associated with the neck fracture. -

Femoral head fractures associated with acetabular fractures (Pipkin type IV)

should be managed in tandem with the acetabular fracture. Generally

this is accomplished operatively by an experienced pelvic surgeon (6,7,8).

-

-

-

Mechanism of injury.

These fractures result from a blow on the greater trochanter or with

axial loading of the thigh with the limb in an abducted position. -

Physical examination. These patients often have multiple injuries, so the management of the patient is the same as outlined in Chap. 1.

A careful examination of the sciatic nerve function must be conducted

with detailed sensory exam to light touch and motor grading of all

distal muscle groups. The muscles innervated by the femoral and

obturator nerves must also be examined because they can occasionally be

injured with complex anterior column fractures. The anteroposterior

pelvis admission trauma film and the two 45-degree pelvic oblique views

described by Judet (see Selected Historical Readings) (Fig. 22-1), as well as a CT scan of the pelvis (6,7,8,9),

are used to evaluate the fracture pattern. The scan is helpful in

determining the presence of intraarticular bone fragments, femoral head

fractures, and displacement in the weight-bearing region of the

acetabulum (12). Roof arc measurements are useful for treatment planning (Fig. 22-1). -

Treatment

-

Nonoperative. Traction was once the recommended definitive treatment for all acetabular fractures (19).

With modern techniques, nearly all significantly displaced acetabular

fractures can be fixed safely and effectively, even in elderly

individuals (20,13,6,7,8,9).

As definitive therapy, traction is not currently generally recommended,

with the exception of elderly patients with multiple medical

comorbidities. It is generally reserved for temporary treatment of

displaced transverse acetabular fractures in which the femoral head is

articulating on the ridge of the fracture edge on the lateral portion

of the joint. Traction prevents further cartilage injury and femoral

head indentation; however, it must be heavy (35–50 lb) and with a

distal femoral pin. Trochanteric pins to provide a lateral traction

vector should never be used if open reduction is an option at any time

in the patient’s management. If nonoperative management is selected,

then bed-to-chair mobilization for 6 to 8 weeks is the best option,

followed by gradual return to weight bearing. Total hip arthroplasty is

an effective salvage technique as long as the acetabular anatomy is not

too distorted (15,16). -

Operative. In

young patients, displacement of 2 to 3 mm in the major weight-bearing

portions of the acetabulum is an indication for open reduction (6,7,8,9).

Numerous surgical approaches to reduction are available, including the

Kocher-Langenbach posterolateral approach, the ilioinguinal, the

extended iliofemoral, and combined approaches. These procedures should

be undertaken by experienced acetabular surgeons because the techniques

for reduction and fixation are numerous and require much special

equipment; inferior results are documented by surgeons who are

inexperienced (13). Postoperatively, CPM is

occasionally used; patients are mobilized with 12 weeks of “touch down”

weight bearing with crutches. If posterior wall involvement is

significant, then flexion is restricted to 60 degrees for the first 6

weeks. Complications include infection (1%–2%), heterotopic

ossification (4%–6% functionally limiting), avascular necrosis (5%),

deep venous thrombosis (10%–20%), pulmonary embolus (1% fatal),

degenerative arthritis (20%–30%, generally associated with posterior

wall fractures), and sciatic nerve injury (2%–5%) (13,14,20,21,22,23). Occasionally, acute hip replacement is indicated in older patients with complex fractures.P.313Heterotopic ossification is most commonly associated

with extended posterior (the extended iliofemoral) and combined

approaches (21). All of these complications

occur more often when surgeons are inexperienced. Effective prophylaxis

includes indomethacin, 25 mg t.i.d for 6 weeks, and low-dose

irradiation (800–1,000 R) in the first week postoperatively (13,22). The use and relative benefits of radiation therapy and indomethacin remain controversial.

-

should be dealt with by internal fixation; then the acetabular injury

should be treated as outlined previously (6,7,8,9). Attempts at treating both injuries by traction have not been satisfactory.

Classic balanced traction with a half or a full ring Thomas splint is

not only cumbersome but also restricts the use of the hip in the muscle

rehabilitation program. A hip exerciser such as that described by Fry

should be considered. These techniques must be learned because they are

occasionally needed in treating problems associated with severe

preexisting systemic disease or local skin problems.

-

Immediate reduction is essential. Delaying reduction for more than 24 hours increases the incidence of avascular necrosis.

-

Weight bearing should be prohibited for 3 months

(a spica cast is recommended for children younger than 8 years of age),

at which time it usually is possible to determine the degree of

avascular necrosis, although a 3-year follow-up period is necessary to

assess this complication fully. Institution of prompt treatment and

protected weight bearing as for Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease probably is

indicated. Recurrent dislocation can occur in children who are not

immobilized. -

When reduction is achieved rapidly with no gross associated trauma, the results are usually satisfactory,

especially in patients younger than 6 years old. The incidence of

avascular necrosis, however, has been reported to be approximately 5%

to 10%.

pelvic radiograph and physical examination. Leg is shortened and

internally rotated for posterior dislocation and flexed and externally

rotated for anterior dislocation. Judet views and CT scan are obtained

after redcuction.

pelvis radiograph and physical examination these nearly always

accompany a hip dislocation, 90% of which are posterior dislocations

of hip (see previous discussion) followed by CT scan to assess size and

reduction of fragment. If reduction is anatomic, limited weight bearing

with crutches for 6 weeks

Surgical approach of ilioinguinal, Kocher-Langenbach or extended

approach based on fracture pattern and experience of surgeon; fixation

with lag screws and reconstruction plates; limited weight bearing for

12 weeks

SS, Moulton A, Srikrishnamurthy K. An analysis of the late effects of

traumatic posterior dislocation of the hip without fractures. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1983;65:150–152.

JM. Fractures of the acetabulum: accuracy of reduction and clinical

results in patients managed operatively within three weeks after the

injury. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1996;78:1632–1645.

Pierre RK, Oliver T, Somoygi J, et al. Computerized tomography in the

evaluation and classification of fractures of the acetabulum. Clin Orthop 1984;188:234–237.

FA, Bone LB, Border JR. Open reduction and internal fixation of

acetabular fractures: heterotopic ossification and other complications

of treatment. J Orthop Trauma 1991;5:439–445.

BR, Willson Carr SE, Gruson KI, et al. Computed tomographic assessment

of fractures of the posterior wall of the acetabulum after operative

treatment. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2003;85:512–522.

MF, Thorpe M, Seiler JG, et al. Operative management of displaced

femoral head fractures: case matched comparison of anterior versus

posterior approaches for Pipkin I and Pipkin II fractures. J Orthop Trauma 1992;6:437–442.

N, Matta JM, Bernstein L. Heterotopic ossification following operative

treatment of acetabular fracture. An analysis of risk factors. Clin Orthop 1994;305:96–105.

LX, Rush PT, Fuller SB, et al. Greenfield filter prophylaxis of

pulmonary embolism in patients undergoing surgery for acetabular

fracture. J Orthop Trauma 1992;6:139–145.