DISLOCATIONS AND LIGAMENTOUS INJURIES OF THE DIGITS

III – THE HAND > Trauma > CHAPTER 39 – DISLOCATIONS AND

LIGAMENTOUS INJURIES OF THE DIGITS

and mobility, the hand allows us to manipulate our environment. The

thumb’s mobile carpometacarpal joint and stable metacarpophalangeal

(MP) and interphalangeal (IP) joints allow both precision pinch and

power movements, including grasp. The stable carpometacarpal joints of

the index and long fingers provide for stability along the central

longitudinal axis of the hand, whereas the relatively mobile ring and

little carpometacarpal joints provide mobility to allow cupping or

flattening of the hand. The hingelike MP and especially the IP joints

allow the ability to grasp objects of varying size.

forces, dislocations and ligamentous injuries of the digital joints are

quite common (396,397). Proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint injuries are probably the most common joint injuries in the hand (68,128).

Fortunately, in the acute phase, most digital dislocations and ligament

injuries can be treated by closed or nonoperative means. This chapter

discusses these topics by joint. The fingers are covered as one, except

where a specific injury to a specific joint in a specific finger

requires individual attention. The joints of the thumb are addressed

separately. A general treatment algorithm is provided at the beginning

of each section.

similar in that their stability is provided by a series of ligaments.

The major stabilizers of these joints include the volar plate and the

collateral ligaments. The volar plate is a fibrocartilaginous structure

firmly attached to bone distally, with a filmy proximal recess. On the

sides of each joint are the collateral ligaments, which blend palmarly

with the accessory collateral ligaments. The shape of these collateral

ligaments varies from a slightly fanlike shape at the proximal IP level

to very fan-shaped at the MP joint.

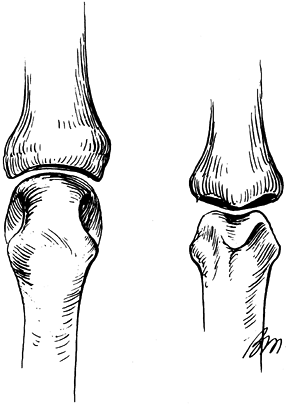

similar in configuration. The PIP joint is a hinge or ginglymus joint,

consisting of a convex bicondylar proximal phalangeal head articulating

with the biconcave middle phalangeal base. It allows approximately 100°

to 110° of flexion. A centrally located proximal phalangeal notch

articulates with a corresponding middle phalangeal median ridge (Fig. 39.1).

Dorsally, the central slip attaches to a tubercle on the base of the

middle phalanx. Palmarly, the volar plate forms the floor of the joint.

The volar plate has a thickened distal fibrocartilagenous portion that

is thicker along its lateral edges. The volar plate attaches along the

volar base of the middle phalanx, blending with the volar periosteum of

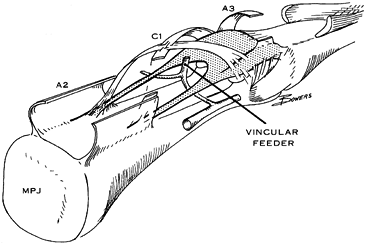

the middle phalanx centrally and the collateral ligaments laterally (Fig. 39.2) (12,14,15,20,28,38,76,77,82,95,137). The proximal portion of the volar plate tapers along its lateral edges to form two check-rein ligaments (Fig. 39.3) (12,14,15,82).

Laterally, the collateral ligaments consist of a thicker dorsal

cordlike collateral ligament proper, and a thinner volar accessory

component (76,91,137).

The collateral ligaments arise from a concavity along the lateral

aspect of the proximal phalangeal head. The ligaments pass obliquely

and palmarly to attach distally into a volar lateral tubercle on the

base of the middle phalanx and along the distal lateral margin of the

volar plate. The volar plate provides resistance to hyperextension

injuries of the PIP joint. Resistance to lateral stresses are provided

mostly by the collateral ligaments and secondarily, if at all, by the

volar plate (68,114). Some stability is also afforded by the surrounding tendon and retinacular system (15,82,124).

Disruption of at least two portions of the volar plate and two

collateral ligaments must occur for displacement of the PIP joint (30).

|

|

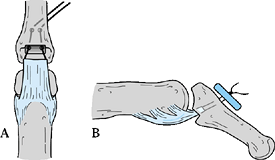

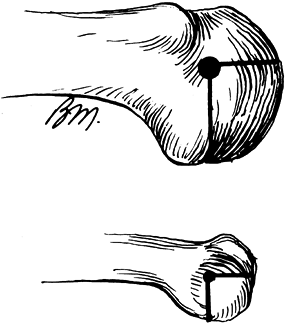

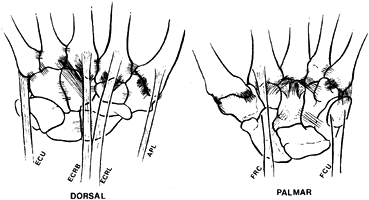

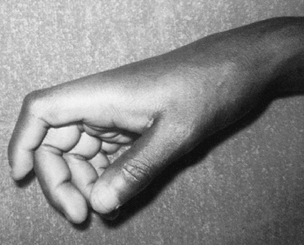

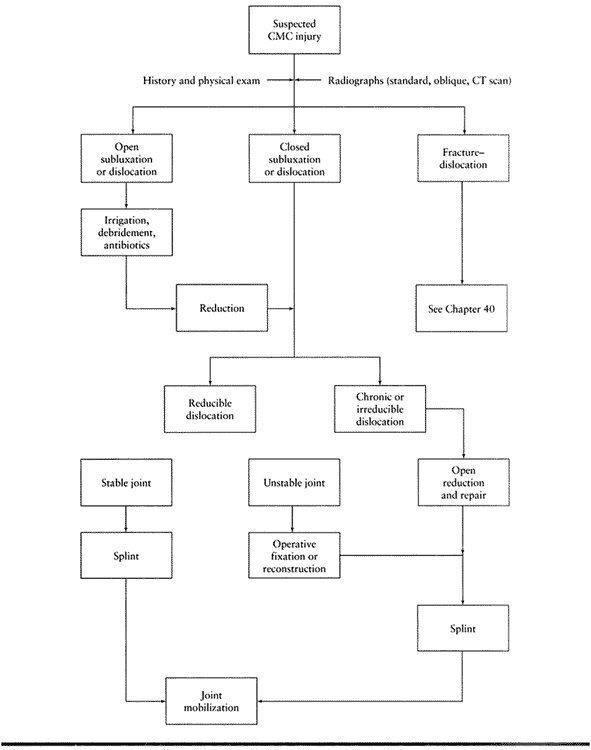

Figure 39.1. The fit of the articular surfaces of the metacarpophalangeal joint (left) and proximal interphalangeal joint (right). (From Green DP, Butler TE. Fractures and Dislocations in the Hand. In: Rockwood CA, Green DP, Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, eds. Fractures in Adults, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1996:677, with permission.)

|

|

|

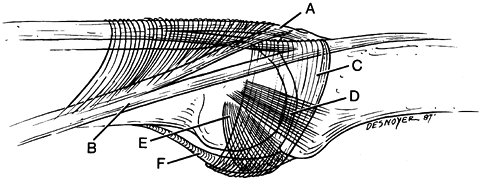

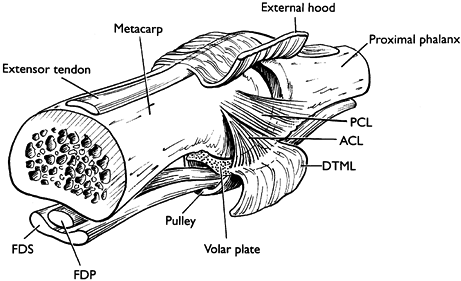

Figure 39.2.

Basic anatomy of the proximal interphalangeal joint. A, central extensor slip; B, intrinsic lateral band; C, transverse retinacular ligament; D, dorsal cord portion collateral ligament; E, accessory collateral ligament; F, volar plate. (From Vicar AJ. Proximal Interphalangeal Joint Dislocations without a Fracture. Hand Clin 1988;4:5, with permission.) |

|

|

Figure 39.3. The proximal portion of the volar plate tapers along its lateral edges to form two check-rein ligaments. (From Bowers WH, ed. The Interphalangeal Joints. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1987, with permission.)

|

the stability provided by the collateral ligaments and volar plate, has

some dynamic stability provided by the insertions of the flexor

digitorum profundus and the terminal

tendon of the extensor mechanism on the base of the distal phalanx.

consisting of a relatively ovoid metacarpal head articulating with an

elliptical cavity at the base of the proximal phalanx. The metacarpal

head is narrower dorsally than palmarly in the sagittal plane, and it

has a proportionately larger anteroposterior diameter than that of the

phalangeal head (Fig. 39.4). Joint motion is

primarily in the sagittal (flexion–extension) plane, but both coronal

(abduction–adduction) plane and small circumduction movements also

occur (217).

|

|

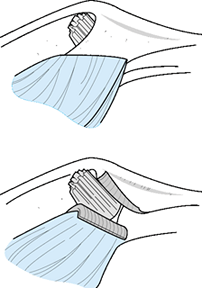

Figure 39.4. Comparison of the metacarpal head (top),

which is narrower dorsally than volarly in the sagittal plane and has a proportionately larger AP diameter than that of the phalangeal head (bottom). (From Green DP, Butler TE. Fractures and Dislocations in the Hand. In: Rockwood CA, Green DP, Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, eds. Fractures in Adults, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1996:677, with permission.) |

the base of the proximal phalanx. Volarly, the joint capsule blends

with the volar plate, which consists of a thick fibrocartilagenous

distal portion and a thin membranous proximal portion. The volar plate

is more securely attached to the proximal phalanx than to the

metacarpal neck. The volar plate is also continuous medially and

laterally with the deep transverse metacarpal ligament (Fig. 39.5) (162,167,172,173,192,217).

Dorsally, the MP joint capsule is thin, and it is reinforced by a loose

insertion of the common extensor tendon. The collateral ligaments

extend from the metacarpal head to the base of the proximal phalanx,

and they also insert into the volar plate. In addition, the metacarpal

origin of the collateral ligament is more dorsal than its counterpart

at the PIP joint (207). These factors dictate that the collateral ligaments of the MP joint are at their longest or most taut in full flexion (Fig. 39.6),

while those of the PIP are most taut at only a few degrees of flexion.

It is important to remember this when testing for collateral ligament

stability or when determining

the

tension appropriate for a repaired ligament, both during the repair and

after surgery. Additionally, the sagittal bands and intrinsic muscle

tendons provide secondary support to the MP joints (124).

|

|

Figure 39.5.

Basic anatomy of the proximal interphalangeal joint. A, central extensor slip; B, intrinsic lateral band; C, transverse retinacular ligament; D, dorsal cord portion collateral ligament; E, accessory collateral ligament; F, volar plate. (From Vicar AJ. Proximal Interphalangeal Joint Dislocations without a Fracture. Hand Clin 1988;4:5, with permission.) |

|

|

Figure 39.6.

The collateral ligaments of the metacarpophalangeal joint are taut with the joint in flexion and lax with the joint in extension. |

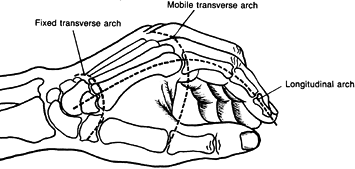

a fixed, stable central unit that comprises the index and long CMC

joints and the relatively mobile radial (thumb) and ulnar units (ring

and little). Together they form the fixed transverse metacarpal arch of

the hand (Fig. 39.7). The index and long finger

metacarpals articulate with the trapezoid and capitate with strong CMC

ligaments, providing relatively little motion (242,244,263,271).

Stability of these joints is provided by tight joint articulations,

thick dorsal capsular ligaments, volar ligaments, interosseous

ligaments, and by some support of the transverse carpal ligament.

Additionally, insertions of the flexor carpi radialis and extensor

carpi radialis longus into the base of the index metacarpal, and of the

extensor carpi radialis brevis into the base of the long metacarpal

provide some dynamic stability to the these joints (Fig. 39.8).

|

|

Figure 39.7. The carpometacarpal joints of the index through little fingers form the fixed transverse arch of the hand.

|

|

|

Figure 39.8. The carpometacarpal joints with supporting ligaments and tendon insertions. (From Gunther SF. The Carpometacarpal Joints. Orthop Clin North Am 1984;15:25, with permission.)

|

relatively mobile, providing approximately 10° to 30° of flexion and

extension, respectively, as well as a few degrees of supination (212,244).

They articulate with two separate hamate facets. A slightly convex

fifth metacarpal base articulates with a slightly concave ulnar hamate

facet, whereas a somewhat flatter fourth metacarpal articulates with

the radial hamate facet. Stability to these joints is provided by the

carpometacarpal and interosseous ligaments. Additionally, the

hypothenar muscles and insertions of the extensor carpi ulnaris and

flexor carpi ulnaris via the pisometacarpal ligament (a continuation of

the

flexor carpi ulnaris insertion) provide some dynamic stability to these joints.

of external forces. These forces can be direct (crush, burns,

lacerations) and/or indirect forces (rotational, bending, axial

loading). With indirect forces, the direction of the deforming force

determines the type of joint injury, while the amount of force dictates

whether the injury is a subluxation or a dislocation. For instance,

dorsal PIP joint dislocations are often accompanied by a longitudinal

compressive force; the magnitude of compression affects the complexity

of the injury. When greater longitudinal compressive forces are

combined with a hyperextension deforming force, dorsal PIP

fracture–dislocations are produced. The mechanism of injury for a

particular joint disorder is further discussed with each specific

injury.

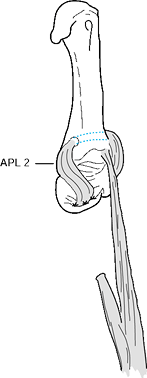

frequently accentuate the deformity. For instance, insertion of the

abductor pollicis longus on the base of the thumb metacarpal, and of

the adductor pollicis on the metacarpal shaft, will accentuate a thumb

CMC joint dislocation or fracture–dislocation.

direct forces or excessive indirect forces, can produce open wounds or

neurovascular injuries. These injuries will ultimately affect the

course of treatment. The treatment of an open dislocation with

neurovascular compromise is different from that of a simple closed

injury.

ligament injuries is to restore functional, pain-free, and stable joint

motion. To accomplish this goal requires an early, accurate evaluation

and diagnosis of the injury and adequate treatment. The goal of

treatment for injuries seen late is usually to provide pain relief.

extension, flexion, lateral deviation force) and timing of the injury

(acute versus chronic). Examine for active joint range of motion,

neurovascular status, flexor and extensor tendon function, areas of

localized tenderness, and, finally, passive joint stability.

and simple can be treated by nonoperative means. Digital block or nerve

block anesthesia can be helpful in evaluating joint stability or

reducing dislocations, but this is often unnecessary. Determine and

record the neurologic status prior to an anesthetic or treatment of the

injury.

examination, but good radiographs in at least two orthogonal planes

(perpendicular to one another) are necessary. With a digital injury,

radiographs of the digit (not of the hand) before and after treatment

are needed to accurately assess any associated fractures, as well as

the efficacy of treatment.

If used, anesthesia (usually a digital block or intraarticular

injection) is helpful to reap the maximum benefit from a stress view.

Similarly, stress views of the injured joint under fluoroscopy, when

compared to the uninjured joint in the opposite hand, can be helpful in

detecting ligament injuries (Fig. 39.9B).

|

|

Figure 39.9. A:

AP radiograph with lateral stress applied to the proximal interphalangeal joint. Lateral deviation of more than 20° is indicative of a complete collateral ligament injury. B: Fluoroscopic stress view of the thumb MP joint showing lateral subluxation of the proximal phalanx. |

evaluating particular joint injuries. An oblique view (Brewerton view)

of the metacarpal heads may be helpful in detecting small metacarpal

head fractures (171,185,189,206).

The Brewerton view is taken as an anteroposterior (AP) view of the hand

with MP joints of the hand flexed approximately 65° and the x-ray beam

tilted 15° from an ulnar to radial direction (185). Evaluation of the thumb CMC joint requires a true AP view and a lateral view of the joint (Robert view) (403).

The AP radiograph is taken with the hand fully pronated and with the

dorsum of the thumb lying flat on the x-ray plate. The x-ray beam is

then centered over the thumb CMC joint. The lateral radiograph of the

joint is taken with the radial side of the thumb lying on the x-ray

plate (thumbnail lying perpendicular to the plate) and the x-ray beam

centered over the joint. Evaluation of the finger CMC joints will

frequently require oblique views of the hand. Occasionally, due to the

difficulty in evaluating these joints, tomography or computed

tomography (CT) may be needed.

stability (full active range of motion) and passive stability

(passively applied medial–lateral and anterior–posterior stress). If

the injury is amenable to closed treatment, use

a

cast dressing that immobilizes the hand and wrist as well as all the

fingers and, if necessary, the thumb. Take care when using a digital

splint, as an acutely injured digit can be further harmed by

immediately taping it to a digital splint. After surgical intervention,

a similar cast dressing is applied.

changed within 5 days. Begin an appropriate active motion program,

modifying for the specific injury. The same is recommended for many

postoperative cases. The goal is to provide joint stability and

adequate protection against reinjury or disruption of the repair while

gaining maximal motion to prevent tendon adherence or joint stiffness.

interphalangeal, metacarpophalangeal, and carpometacarpal joints can be

classified similarly. Classification can be based on the status of the

skin (closed versus open), the duration of injury (acute versus

chronic), the degree of joint displacement (subluxation versus

dislocation), the status of the joint surface (dislocation versus

fracture–dislocation), and the ability to reduce the joint dislocation

(simple versus complex).

joint soft tissue supporting structures, but some contact remains

between the articular surfaces. With dislocations, there is a loss of

contact between the joint surfaces. Joint dislocations and subluxations

can be further subclassified based on the direction of displacement of

the distal portion of the injured digit relative to the proximal

portion, that is, dorsal, lateral, or palmar (volar) dislocations.

open injuries are common (Table 39.1).

Assess these structures and obtain true AP and lateral radiographs of

the digit and particularly of the DIP joint. Open dislocations require

adequate debridement and antibiotics.

|

|

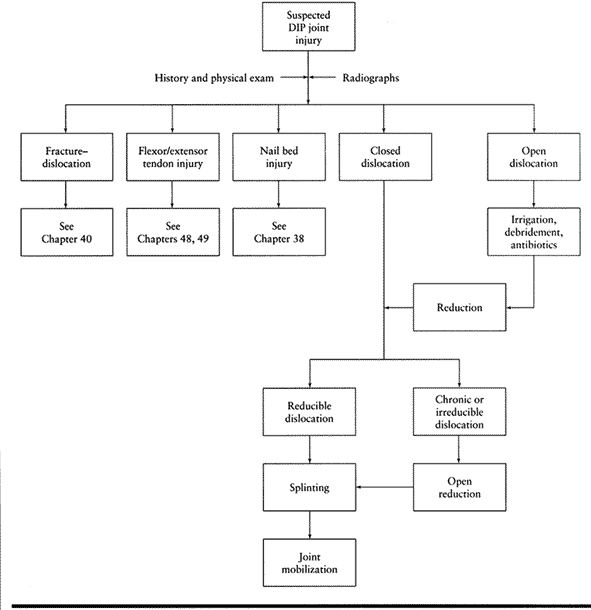

Table 39.1. Algorithm for Assessment of Distal Interphalangeal (DIP) Joint Injuries

|

The more common injuries occur secondary to a hyperextension force

(dorsal dislocation, dorsal lip fracture or fracture–dislocation),

forced extension against resistance (flexor profundus tendon avulsion

injury), flexion injury (extensor tendon avulsion injury), hyperflexion

force

(palmar dislocation), and lateral deviation force (collateral ligament

injury). The addition of a longitudinal compression force usually adds

some form of an intraarticular fracture.

These injuries are usually produced by a longitudinal compression and

hyperextension of the joint. Occasionally, a lateral, and even less

commonly a palmar, dislocation can occur. Look for flexor (jersey

finger) (Chapter 48) or extensor tendon (mallet finger) (Chapter 49)

avulsion injuries, which are common. Simultaneous dislocation of the

distal and proximal interphalangeal joints has been described and

should be detectable by careful clinical examination and adequate

radiographs of the injured digit (5,6,9,32,45,47,50,52,54,57,73,75,99,117,139,142).

-

Perform a closed reduction, with or without digital block anesthesia, using longitudinal traction on the distal phalanx.

-

Place direct pressure on the dorsal base of the distal phalanx, displacing it distally and palmarly.

-

Postreduction radiographs should confirm congruous reduction of the joint.

-

After joint reduction, assess joint

stability and flexor and extensor tendon function. If joint instability

is present after joint reduction, splint the joint for 2 to 3 weeks in

10° to 20° of flexion (for dorsal dislocations). -

With a palmar dislocation, dorsal lip

fracture–dislocation, or terminal extensor tendon avulsion (mallet

finger) injury, avoid splinting the DIP joint in hyperextension. This

prevents dorsal skin wound problems. Splint, generally, for 6 weeks or

more to promote healing (see Chapter 49). Fracture–dislocations of the joint can occur (46,51). -

If the flexor digitorum profundus is avulsed with the volar fragment, reattach the tendon.

-

Open dislocations of the DIP joint are

frequent and require irrigation, debridement, and antibiotics. Repair

any associated nail bed injuries or nail plate avulsions. -

When the dislocation is chronic (greater

than 3 weeks) or irreducible, perform an open reduction. Irreducible

DIP joint dislocations may be secondary to interposed volar plate,

flexor tendon, fracture fragment, or a sesamoid bone (32,44,53,58,67,70,98,103,107,108,112,118,122,123,130,133,150). Remove the interposed structure to reduce the joint.

-

Make a straight dorsal midline,

transverse, or H-shaped incision and split the extensor tendon

longitudinally in the midline. Alternatively, divide the tendon

transversely and repair it at the time of closure. -

If the volar plate is interposed between the joint surfaces, incise as much of it as necessary to displace it palmarly.

-

Release the collateral ligaments

subperiosteally at their insertion into the middle phalanx and continue

the dissection until the joint can be reduced. Test the joint for

stability. -

If the joint is grossly unstable,

transfix the joint with smooth 0.035–0.045 Kirschner (K-) wire(s) for 3

weeks. If the joint is fairly stable, immobilize it in a splint for a

few days for comfort. -

Then apply a dorsal-block splint and allow active flexion. Remove the splint after 3 weeks.

-

If the joint surface damage is extensive, perform a primary arthrodesis (see Chapter 72).

will usually occur from a failure in diagnosis, from a delay in

treatment, or from undertreatment. Failure to recognize a concomitant

injury to soft tissues (e.g., flexor or extensor tendons) will result

in a deformity (e.g., jersey finger or mallet finger) (186).

Unrecognized dislocations generally require an open reduction and pin

fixation, instead of a closed reduction. Delayed reduction of the joint

may also result in significant articular damage, necessitating an

arthrodesis. Redislocation of a dorsal DIP joint dislocation can occur

if hyperextension is not prevented for at least 3 weeks.

injuries of the DIP joint are partial tears or sprains at the DIP joint

level and thus can be treated nonoperatively. Temporary splinting for a

few days for comfort should be followed by an early, vigorous active

motion program.

subluxations are frequently associated with an injury to the volar

plate, collateral ligament, extensor tendon (central slip), and joint

articular surface (Table 39.2). Assess these

structures and take true AP and lateral radiographs of the digit,

particularly of the PIP joint. Stress views to assess collateral

ligament injuries may be helpful. Open dislocations require adequate

debridement and antibiotics.

|

|

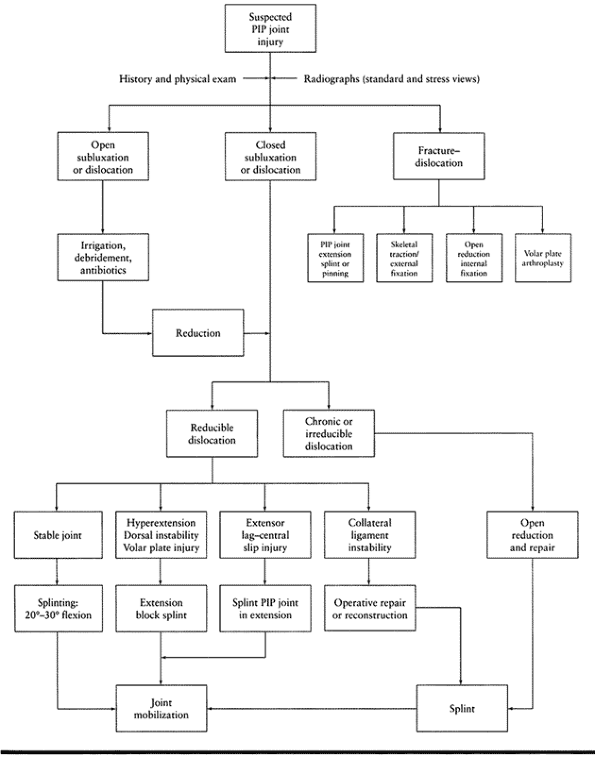

Table 39.2. Algorithm for Assessment of Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) Joint Injuries

|

ranging from a simple hyperextension injury, as seen in sporting

injuries, to a severely comminuted fracture. The more common injuries

occur secondary to a hyperextension force (dorsal subluxation or

dislocation,

volar

plate rupture), longitudinal compression and hyperextension force

(dorsal fracture–dislocation), lateral deviation force (collateral

ligament injuries), and combined rotatory and longitudinal compression

force (rotatory dislocations).

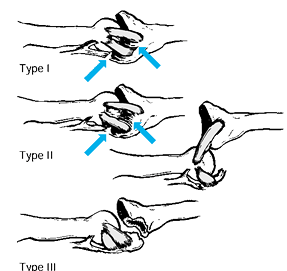

However, generally three types can be categorized depending on the

degree of hyperextension force applied to the joint and any associated

fractures (28,38).

-

Type I is a hyperextension injury to the joint with subluxation but not dislocation.

-

Type II is a dorsal dislocation.

-

Type III is a shear fracture of the volar base of the middle phalanx, producing a fracture–dislocation (Fig. 39.10).

Type I injuries are associated with avulsion of the volar plate, and a

partial horizontal split occurs between the volar and dorsal portions

of the collateral ligaments. Type II injuries are associated with a

complete avulsion injury of the volar plate and a greater longitudinal

tear of the collateral ligaments (12,18,28,38).![]() Figure 39.10. Three types of dorsal PIP joint hyperextension injury (see text for description of injuries).

Figure 39.10. Three types of dorsal PIP joint hyperextension injury (see text for description of injuries).

reduced by closed means. A digital block is often unnecessary. The

volar plate, by necessity, is ruptured, usually from the middle

phalanx, but the collateral ligaments rarely are ruptured completely

from their attachments (10,12).

Perform reduction with longitudinal traction and direct pressure on the

dorsal base of the middle phalanx, displacing it distally and palmarly.

Confirm congruous reduction of the joint with postreduction

radiographs. Assess both active and passive stability of the joint

after reduction. With type I and II dorsal dislocations, the joint is

usually stable after reduction (56,126).

Type III injuries are discussed in the following section. Use a resting

splint with the finger flexed to 20° to 30° for 7–10 days. Do not

splint the digit in flexion for an extended period of time, and begin

early active motion with protection against hyperextension.

Alternatively, use an orthoplast figure-eight splint, preventing joint

hyperextension (79). Protect the injured digit,

especially during sporting activities, by taping it to the adjacent

uninjured digit. Reassure the patient that persistent swelling and slow

resolution of stiffness is to be expected.

and require open reduction. An attempt at gentle closed reduction under

adequate anesthesia is permissible but is best done in the operating

room; if it is unsuccessful, the joint then can be approached

surgically.

-

Make a straight or slightly curvilinear dorsal longitudinal incision.

-

Divide the central slip of the extensor

mechanism in the midline but do not dissect distal to the base of the

middle phalanx, as the attachments of the central slip to the middle

phalanx and triangular ligament must remain intact. -

If the volar plate is interposed, split

the interval between it and each accessory collateral ligament.

Mobilize the volar plate and perform a trial reduction of the joint. -

If this fails, release the origins of the

collateral ligaments from the proximal phalanx by sharp subperiosteal

dissection. This should allow reduction if the joint is hyperextended

and the volar plate is pushed palmarward. -

After reduction, test the joint for

instability. If instability is present, transfix the joint with smooth

0.035–0.045 K-wire for 3 weeks. -

If the joint is fairly stable, close the

extensor split and the skin separately with nonabsorbable sutures. Take

postreduction radiographs to confirm congruous reduction of the joint. -

Immobilize the hand in a cast dressing

with the PIP joints flexed no more than 10°. After 5–7 days, begin

active flexion for an additional 2–4 weeks, using a dorsal

extension-block splint to prevent hyperextension of the joint.

the volar plate (also referred to as a pseudoboutonnieére deformity) (90,91).

A significant contracture can be treated with dynamic splinting, serial

casting, or, eventually, surgical release of the contracture (25,38,80,88,140).

joint hyperextension is not prevented for at least 3 weeks, either

redislocation of the joint or a chronic swan-neck deformity may occur (104).

A true lateral radiograph will help guard against persistent

subluxation. With a chronic swan-neck deformity, painful snapping of

the lateral bands over the phalangeal heads or inability to initiate

joint flexion may occur. Treatment includes primary reattachment of the

volar plate or sublimis tenodesis (see the section below on volar plate ruptures) (1,7,12,22,38,72,78,91,109,110,132,136,144,195).

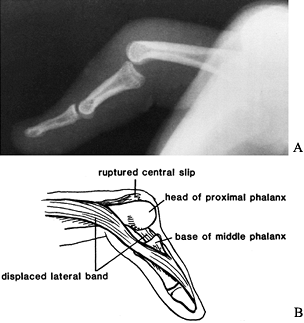

The injury results in volar displacement of the middle phalanx relative

to the proximal phalanx. There is a disruption of the extensor

mechanism (central slip), creating a boutonnieére injury. One proximal

phalangeal condyle may herniate between the central slip and the

lateral band, producing a rotatory or irreducible PIP joint dislocation

(see Rotatory Dislocations). There may be an injury to a collateral

ligament and the volar plate (Fig. 39.11) (33,37).

|

|

Figure 39.11. A: Lateral radiograph of volar proximal interphalangeal dislocation. B: Diagram showing how the boutonnieére develops as the head of the proximal phalanx herniates through the extensor mechanism.

|

-

Reduce a palmar PIP joint dislocation with gentle traction on the middle phalanx with the MP and PIP joints flexed (134,146).

Wrist extension may relax the extensor mechanism. In general, full

passive extension of the joint is obtainable and postreduction

radiographs should confirm congruous reduction of the joint. -

After reduction, test active PIP joint

extension to determine the status of the central slip. With disruption

of the central slip, the PIP joint should be splinted in extension for

4–6 weeks, either with smooth K-wire transfixing the joint or simply

with an external splint. -

The DIP and MP joints should be permitted

to move so that the extensor mechanism is less likely to become

adherent. If the dislocation is irreducible or chronic (34,106,110,111), surgery is necessary.

-

Make a straight dorsal or slightly curvilinear incision.

-

Mobilize the lateral bands so that the head of the proximal phalanx is no longer caught between them.

-

Reduce the joint, and transfix it in extension with smooth 0.035–0.045 K-wire.

-

Reattach the central slip to the base of

the middle phalanx with nonabsorbable sutures to remaining periosteum,

through bone holes, or with miniature suture anchors. Repair the

interval between each lateral band and the central slip with

nonabsorbable sutures. Postreduction radiographs should confirm

congruous reduction of the joint. -

Remove the pin after 6 weeks, having allowed active motion at the MP and DIP joints during that time.

joint dislocation tend to be poor, emphasizing the need for early

recognition of the injury (28,34,38,41,106,110,146).

If any or too early PIP flexion is allowed during the immobilization

period, a boutonnieére deformity will result. Treatment of the

boutonnieére deformity varies depending on the duration of the

deformity (35,89).

complex volar-lateral dislocation, is an uncommon injury in which the

middle phalanx is displaced laterally and palmarly (8,21,24,30,36,39,59,61,63,65,69,93,98,100,102,106,110,111,122,127,135,143). The injury occurs secondary to a combined rotatory and compressive force applied to

the PIP joint. Clinically, the PIP joint is swollen and tender. The

digit may be deviated and flexed. In contrast to the palmar PIP joint

dislocation, for which passive extension is possible after reduction,

there is resistance to active and passive flexion and especially to

passive extension.

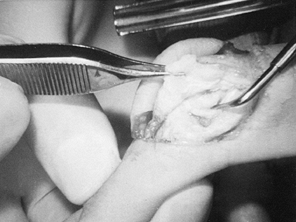

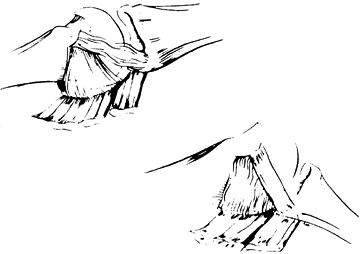

ligament is ruptured and the condyle of the proximal phalanx usually

penetrates through a longitudinal rent between the lateral band and the

central slip (Fig. 39.12). The lateral band is looped through the joint around the condyle, preventing reduction.

|

|

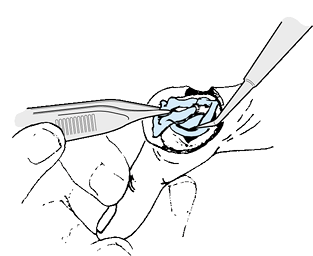

Figure 39.12. A longitudinal rent in the extensor mechanism produced by the condyle of the proximal phalanx (above probe) splits the central slip (held by forceps) from the lateral band (below probe). The band then loops around the condyle and through the joint, preventing reduction.

|

be improved by closed reduction, but there will be a persistent

subluxation and widening of the joint space on the side of injury (Fig. 39.13).

Due to the rotatory nature of the injury, on a true lateral radiograph

of the digit, one phalanx may appear slightly rotated relative to the

other. This persistent subluxation of the joint usually must be treated

surgically. Attempt closed reduction following digital block

anesthesia, with gentle longitudinal traction and finger rotation (20,28,38,134).

Flex the MP and PIP joints to relax the lateral bands, and extend the

wrist to relax the extensor mechanism. Confirm congruous reduction with

radiographs and test for active motion and active and passive

stability. With incomplete active PIP joint extension, splint the joint

in full extension for 3–6 weeks.

|

|

Figure 39.13. AP radiograph showing persistent subluxation or widening on one side of the PIP joint.

|

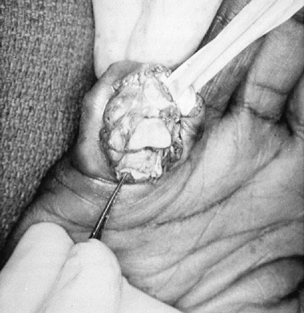

-

Make a mid-axial or dorsal curvilinear

incision angled toward the injured side of the PIP joint. The condyle

protruding between the central slip and the lateral band will be seen

at once (Fig. 39.14).![]() Figure 39.14. Clinical photograph corresponding to Figure 39.12.

Figure 39.14. Clinical photograph corresponding to Figure 39.12. -

Remove the lateral band from the joint with a blunt instrument. The joint will promptly reduce.

-

Repair the collateral ligament if

disruption of the collateral ligament results in persistent joint

instability or subluxation. If the lateral band is not badly damaged,

repair the longitudinal rent in the interval between the lateral band

and the central slip. If the lateral band is severely damaged, excise

it. -

The remaining intact central slip and lateral band are sufficient to provide full extension of the finger (100). Intraoperative postreduction radiographs should confirm congruous reduction of the joint.

-

After 5–7 days of immobilization in a

cast dressing, start active motion, with the finger strapped to the

adjacent finger to protect against reinjury. Protect the finger for 4–6

weeks.

dislocations are usually due to failure to diagnose the dislocation,

causing a delay in treatment that results in a fixed flexion deformity (146).

Incomplete joint reduction results from incomplete removal of the

lateral band. Joint instability results from inadequate collateral

ligament repair. Failure to adequately reduce the joint will result in

a fixed flexion deformity. Late treatment consists of volar plate and

collateral ligament release, excision of the lateral band, and

reduction of the joint (106).

most difficult fracture–dislocation to treat in the hand. As the middle

phalanx displaces proximally and dorsally, the head of the proximal

phalanx is driven into the palmar lip of the base of the middle

phalanx. A comminuted depressed fracture usually results and can

involve 70% or more of the articular surface. These injuries can be

divided into stable and unstable fracture–dislocations (28,38).

In stable fracture–dislocations, the volar lip fracture usually

involves less than 40% of the articular surface. The dorsal portions of

the collateral ligaments remain attached to the middle phalanx. With

unstable fracture–dislocations the volar lip fracture involves more

than 40% of the articular surface. The collateral ligaments usually

remain attached to the volar lip fracture. Dorsal joint subluxation,

which is difficult to reduce and to maintain by closed means, tends to

occur with PIP joint extension.

Dorsal subluxation associated with volar lip middle phalangeal

fractures can occasionally be reduced with PIP joint flexion. Always

try this technique first, since it yields the best results if

applicable (Fig. 39.15). The key to its

usefulness is restoration of the joint alignment, not reduction of the

fracture. If the fracture reduces also, this is a bonus.

|

|

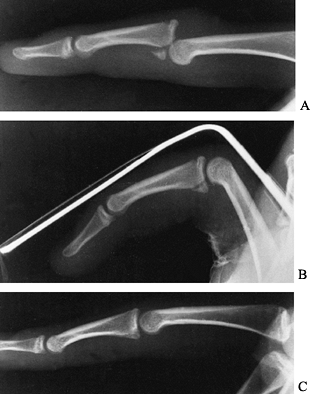

Figure 39.15. Fracture–dislocation of the PIP joint. B:

Joint reduced by flexion of the finger to 60° or more. The fracture reduction (anatomic here) is a bonus but is not necessary for a good result. C: Healed fracture–dislocation with good joint congruity. |

-

Use a padded hand-based aluminum splint

or combine an aluminum splint with a short arm cast. With the latter

technique, a padded aluminum splint loop is taped to a short arm cast

over the top of the finger being tested (Fig. 39.16).![]() Figure 39.16. Extension-block splint.

Figure 39.16. Extension-block splint. -

Fashion the splint so that the PIP joint

is flexed approximately 10° to 15° short of the unstable, dorsally

subluxed position, which is generally between 30° to 40° of PIP joint

flexion. -

A true lateral radiograph of the digit will confirm that the joint subluxation is corrected.

-

Adjust the splint weekly by reducing the

degree of PIP joint flexion by 25%, or approximately 10°. Take

radiographs weekly to ensure that dorsal joint subluxation has not

recurred. -

If joint alignment cannot be restored by

closed means, extension-block splinting should be abandoned and an

alternative procedure used. These measures include extension-block

pinning (135,138), skeletal tractionor dynamic skeletal traction (2,3,17,22,55,97,105,115,119,121), dynamic hinged external fixation (48,49,66,74), open reduction and internal fixation (33,40,60,61,81,86,91,128,141,144,147,148 and 149), and vo-lar plate arthroplasty (11,29,31,60,61,87).

-

Place a smooth K-wire in the proximal

phalangeal head and shaft from a distal to proximal direction at an

angle, with the PIP joint partially flexed, which places it dorsal to

the middle phalanx, and with the dorsal fracture–subluxation reduced. -

The wire prevents dorsal subluxation of the middle phalanx as seen on a lateral radiograph.

-

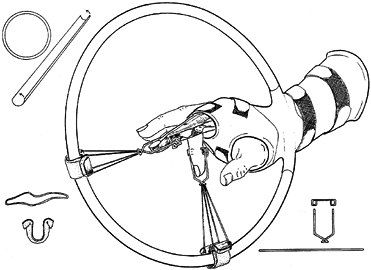

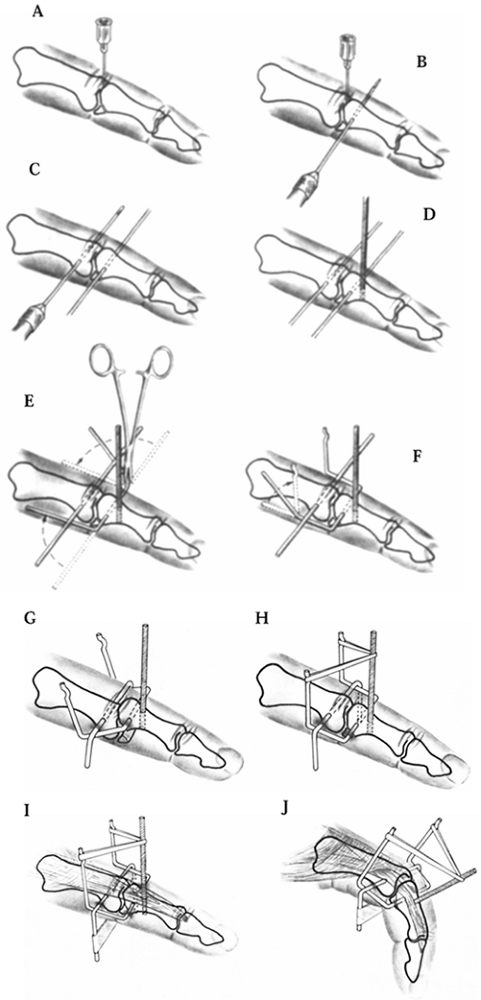

Use a small needle to identify the joint line (Fig. 39.17A).

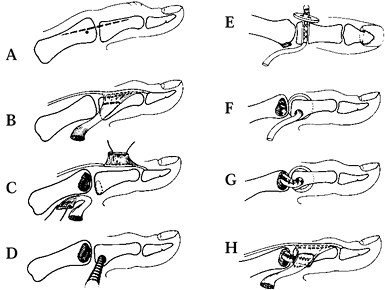

Figure 39.17.

Figure 39.17.

Force-couple splint. See text for a description of each step in the

technique. Agee JM. Unstable Fracture Dislocation of the Proximal

Interphalangeal Joint: Treatment with the Force Couple Splint. Clin Orthop 1987;214:101. -

Insert smooth K-wires transversely into the middle phalangeal base (Fig. 39.17B) and into the center of the proximal phalangeal head (Fig. 39.17C), parallel to the PIP joint articular surface.

-

Place a threaded K-wire in a dorsal to volar direction in the proximal half of the middle phalanx (Fig. 39.17D) and through the dorsal and volar cortices, being careful not to penetrate the flexor tendon.

-

On both sides of the finger, bend the distal K-wire proximally at 90° and pass it proximal and palmar to the proximal wire (Fig. 39.17E).

Make a second 90° bend in the distal wire, 5–10 mm proximal to the

proximal wire, and direct the wire dorsally or vertically (Fig. 39.17F). Bend a hook into the ends of the K-wire to retain a rubber band. -

On both sides of the finger, bend the proximal K-wire at 90° in a palmar direction (Fig. 39.17G). Bend the proximal wire outside of the distal wire.

-

Connect the vertically oriented, threaded

K-wire and the vertical arms of the distal K-wire with a rubber band,

producing linkage, or a force couple (Fig. 39.17H). -

Place adhesive tape around the ends of the proximal K-wire to prevent the two ends of the wire from spreading apart (Fig. 39.17I).

-

The force couple allows joint range of

motion and is used to palmarly displace the middle phalanx and dorsally

displace the proximal phalanx and thereby reduce dorsal subluxation of

the PIP joint fracture–dislocation (2,3) (Fig. 39.17J).

-

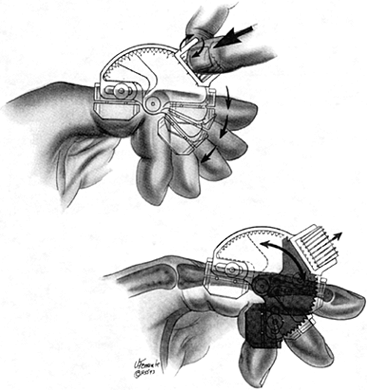

Place a transosseous wire horizontally

into the distal head of the middle phalanx and bend the wire distally

on both sides of the finger at 90° angles. -

Place a loop into the ends of the wire

and connect with rubber bands, the ends of the wire to a sliding

U-shaped thermoplastic component. -

The U-shaped component is looped over a circular 3- or 6-inch-diameter hand/forearm outrigger hoop splint.

-

The rubber band provides traction across the PIP joint. Use of the outrigger splint allows active finger flexion and extension (119,121) (Fig. 39.18).

![]() Figure 39.18.

Figure 39.18.

Outrigger splint. From Schenk RR. The Dynamic Traction Method.

Combining Movement and Traction for Intra-Articular Fractures of the

Phalanges. Hand Clinic 1994;10:187.

-

Under fluoroscopic guidance or open

visualization, place a K-wire horizontally into the proximal phalangeal

head center axis of rotation. -

Place the centering hole of a hinged

external fixator [e.g., the Compass PIP Hinge (Smith and Nephew

Richards, Memphis, TN)] over the central axis pin (Fig. 39.19). Figure 39.19. Placement of the hinged external fixator. From Jones BF, Stern PJ. Interphalangeal Joint Arthrodesis. Hand Clinic 1994;10:267.

Figure 39.19. Placement of the hinged external fixator. From Jones BF, Stern PJ. Interphalangeal Joint Arthrodesis. Hand Clinic 1994;10:267. -

Place smooth K-wires initially through

the proximal and then through the distal pin blocks in the mid-axial

line of the digit. Hold the middle phalanx reduced during K-wire

placement in the distal pin block. -

Apply joint distraction or passive joint motion, as needed, using a built-in distraction screw or worm gear mechanism (Fig. 39.20).

![]() Figure 39.20. Application of joint distraction. From Jones BF, Stern PJ. Interphalangeal Joint Arthrodesis. Hand Clinic 1994;10:267.

Figure 39.20. Application of joint distraction. From Jones BF, Stern PJ. Interphalangeal Joint Arthrodesis. Hand Clinic 1994;10:267.

of the palmar lip fracture is a demanding and often frustrating

technique. If the fragment is sufficiently large and the fracture

fairly fresh, however, internal fixation may provide reasonably good

joint motion. Methods of fixation include K-wires, screw fixation, and

intraosseous wiring.

is an alternative that can be used for acute as well as chronic

injuries. Advancement of the volar plate attempts to restore the

impacted volar articular surface.

-

Make a palmar zigzag incision over the PIP joint.

-

Elevate the flexor sheath from the distal edge of the A2 to the proximal edge of the A4 pulley, protecting the digital arteries and nerves at all times.

-

Retract the flexor tendons without damaging the vincula.

-

Mobilize the volar plate and accessory

collateral ligaments with the attached palmar lip fragment from the

middle phalanx, leaving it attached proximally. -

Excise the remaining collateral ligaments

connecting the proximal and middle phalanges (especially in chronic

cases), and then open the joint by hyperextending it (like a shotgun) (Fig. 39.21). Figure 39.21. PIP joint exposed by opening like a shotgun. From the bottom:

Figure 39.21. PIP joint exposed by opening like a shotgun. From the bottom:

Fracture fragment with attached volar plate, head of proximal phalanx,

base of middle phalanx with defect from compression fracture. -

Debride small or loose fragments. If the

fragment attached to the volar plate is large, fix it with fine smooth

K-wire(s), screws, or an interosseous wire to the middle phalanx, being

careful to establish a smooth articular surface and a congruous joint

reduction. -

Confirm congruous reduction of the joint with postreduction radiographs.

-

More commonly, the volar plate fragment

cannot be used. Dissect it free subperiosteally from the volar plate,

retaining all possible length of the plate. Mobilize the volar plate as

much as possible, leaving its proximal attachment intact, by freeing

any restraining bands in the recess. -

Create a transverse trough in the middle

phalangeal defect at the dorsalmost part of the cancellous defect, near

the palmar margin of the remaining dorsal articular cartilage. The

trough must be perpendicular to the long axis of the middle phalanx.

Place drill holes at the lateral margins of the trough. -

Reduce the PIP joint, and pull the volar plate into the trough with the joint flexed no more than 30° (Fig. 39.22). Tie the suture over a protected button dorsally.

![]() Figure 39.22. A:

Figure 39.22. A:

View from palmar side of volar plate arthroplasty as sutures lead the

distal edge of the volar plate into the trough at the base of the

middle phalanx. B: Lateral view of volar plate arthroplasty, secured with the joint flexed. -

Confirm congruous reduction of the joint

with intraoperative postreduction radiographs. Suture any remaining

collateral ligament to the lateral margin of the volar plate. -

Transfix the joint with a smooth 0.035–0.045 K-wire with the joint in 20° to 30° of flexion.

-

Immobilize the hand in a cast dressing.

Remove the wire at 2 weeks, and encourage active flexion with use of an

extension-block splint. Begin active extension at 4 weeks and extension

splinting at 5 weeks if full extension is lacking. Motion may continue

to improve for several months.

usually due to failure to treat the initial injury adequately or

secondary to loss of reduction of the joint. Persistent joint

dislocation can occur with closed treatment when the joint hinges

instead of reducing congruously, or redislocation occurs with too rapid

mobilization of the joint into extension. Redislocation can also result

from inadequate reduction at surgery, or from failure of the pullout

suture or of internal fixation. Angulation of the joint can occur

secondary to asymmetrical impaction of the volar lip fragment or with

oblique placement of the volar plate bone trough. Flexion contracture

occurs with prolonged immobilization. Posttraumatic arthritis results

from articular damage.

release, repeat open reduction and internal fixation, opening-wedge

osteotomy and bone grafting, volar plate arthroplasty, and joint

arthrodesis (27,28,31,38,64,140,146,149).

Clinically, tenderness occurs over the site of injury, and joint laxity

to lateral stress may be present. Most PIP joint collateral ligament

injuries are incomplete and need only to be protected by strapping to

an adjacent digit for 3–6 weeks (41,96).

However, lateral dislocations of the PIP joint can result in complete,

but uncommon, rupture of a collateral ligament and at least a portion

of the volar plate (28,38). Angulation greater than 20° with lateral stress testing indicates a complete collateral ligament injury (34,68,95) (Fig. 39.9A).

controversial. After closed reduction, assess stability of the joint by

active motion and confirm joint congruency on radiographs. Acutely, use

a temporary splint for comfort, followed by strapping to an adjacent

digit for 3–4 weeks, encouraging full active motion. Repair of the

collateral ligament has been described (4,13,16,41,60,61 and 62,91,94,113,116),

but joint stiffness is a problem. The index radial collateral ligament

is probably the only ligament that needs early surgery (41,62,94).

-

Make a radial mid-axial incision.

-

Divide the transverse retinacular ligament, reflect it, and retract the radial lateral band dorsally.

-

Identify and repair the torn collateral

ligament. The stump usually is still attached at the middle phalanx and

is repaired with nonabsorbable sutures. -

If no residual stump is present, roughen

the bone and drill parallel holes obliquely across the phalanx. Pass a

nonabsorbable suture, using a modified Bunnell suture technique,

through the torn edge of the ligament. Pass the two suture ends through

the holes in the bone and out through the skin. Tie the suture over a

protected button with the joint reduced and the ligament pulled taut.

Miniature suture anchors can be used instead of a transosseous pullout

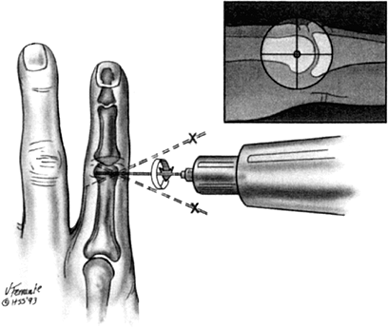

suture technique (Fig. 39.23). Figure 39.23. Miniature suture anchors can be used instead of a pullout suture technique to repair the collateral ligament.

Figure 39.23. Miniature suture anchors can be used instead of a pullout suture technique to repair the collateral ligament. -

Repair the accompanying partial tear of the volar plate as well.

-

Repair the retinacular ligament, close the skin, and confirm congruous reduction of the joint with radiographs.

-

Splint the digit in no more than 20° of

PIP joint flexion for 5–7 days and then start active motion with

adjacent finger-strapping for an additional 2–3 weeks.

sufficiently symptomatic to require reconstruction. Often, there are

degenerative changes in the joint, and ligament reconstruction cannot

be expected to alleviate symptoms due to arthritis. Once again, if

reconstruction of a chronic PIP collateral ligament rupture is

necessary, it is on the radial side of the index finger.

shortening or imbricating the remaining ligament or by augmenting the

repair, usually with a slip of the superficialis (78,91,104,113).

-

Make a surgical approach similar to that made for the acute collateral ligament injury.

-

Identify the ligament and dissect it

free. Imbricate it in its midportion, or shorten it and suture it with

a nonabsorbable suture at the proper length. -

If further reinforcement is needed,

separate the radial slip of the superficialis, leaving it attached

distally detaching it proximally. Pass the tendon through a drill hole

in the head of the proximal phalanx with a pullout suture and tie the

suture over a protected button on the ulnar side of the proximal

phalanx. -

Alternately, pass the superficialis

through two holes drilled on the radial aspect of the proximal

phalangeal head and suture the tendon to itself. Spread out the tendon

dorsally and suture its radial (now dorsal) edge to the remaining

fibers of the collateral ligament. -

Close the wound as previously described.

After 10 days of immobilization in no more than 20° of flexion,

encourage the patient to actively exercise with strapping to the

adjacent long finger for an additional 4–5 weeks.

dislocations usually occur from inadequate initial treatment, and they

are frequently an expected outcome of the injury, even with adequate

treatment. Pain, instability, loss of motion, and arthrosis can occur

from incomplete joint reduction, lateral translocation, or uneven

forces within the joint secondary to excessive scarring (146).

perfectly stable joint. Potential problems of ligament reconstruction

include joint stiffness or persistent laxity.

dorsal PIP joint dislocation or hyperextension injury (type 1 dorsal

PIP joint dislocation). The volar plate usually detaches distally from

the middle phalanx, with or without a piece of bone. If the volar plate

ruptures distally with a small fragment of bone (as seen on the lateral

radiograph), the joint is inevitably congruous. This injury must be

differentiated from the serious PIP joint fracture–dislocation. Treat

the minor volar plate fracture as any other volar plate injury, with

protection against hyperextension by either a temporary dorsal-block

digital splint or by strapping to an adjacent finger for 3 weeks.

Encourage full flexion.

deformity with dorsal subluxation of the lateral bands. Painful flexion

of the PIP joint can occur as the lateral bands sublux palmarly over

the proximal phalangeal condyles. Distinguish this swan-neck deformity

from the type of swan-neck deformity secondary to an extensor terminal

tendon disruption (mallet finger). With volar plate insufficiency, the

patient will be able to actively extend the DIP

joint

with the PIP joint held in full extension. Nonoperative treatment

includes use of a orthoplast or silver (double-ring) splint to help

prevent PIP joint hyperextension (Fig. 39.24). Symptomatic volar plate ruptures (Fig. 39.25)

can be helped by surgical correction. Options include late reattachment

or shortening of the volar plate, with or without some form of volar

reinforcement (1,7,12,22,72,78,91,104,109,132,136,144).

|

|

Figure 39.24.

Silver ring (or double-ring) splint used for swan-neck deformity to prevent hyperextension at the PIP joint. The splint can be padded if it irritates the dorsum of the digit. |

|

|

Figure 39.25. Chronic volar plate rupture in a basketball player; it subluxated each time he caught the ball.

|

-

Make a palmar zigzag incision and release the flexor sheath between the A2 and 4 pulleys.

-

Protect the digital vessels and nerves

while retracting the flexor tendons to expose the volar plate. If it

has been ruptured in midsubstance and repair is possible, suture the

edges directly. -

More often, it will be detached distally (Fig. 39.26A).

In that case, roughen the base of the middle phalanx and create a

transverse trough. Place a nonabsorbable suture in the distal end of

the volar plate with a modified Bunnell suture technique. Place drill

holes at the lateral margins of the trough in a distal but somewhat

lateral direction so that the extensor mechanism will not be injured or

trapped by the passing of the pullout suture. Pass the ends of the

suture from the volar plate through the drill holes, and tie them over

a protected button. To prevent tethering of the distal extensor

mechanism, flex the DIP joint 30° when passing the sutures dorsally. As

the suture is tied, flex the PIP joint. Apply gentle traction on the

suture so the distal end of the volar plate is pulled snugly into the

trough (Fig. 39.26B).![]() Figure 39.26. A: Volar plate rupture usually occurs distal from the base of the middle phalanx. B:

Figure 39.26. A: Volar plate rupture usually occurs distal from the base of the middle phalanx. B:

The distal margin of the volar plate is pulled snugly into a trough in

the middle phalanx and secured through drill holes in the bone. -

If there is not enough of the volar plate

left to advance or repair, a volar reinforcement procedure can be used.

With this technique, isolate either slip of the superficialis. Leave it

attached distally and detach it proximally under the A2 pulley. -

Place a drill hole transversely in the

neck of the proximal phalanx. Draw the proximal end of the detached

superficialis slip into the hole, using a pullout nonabsorbable suture,

and tie it over a protected button (Fig. 39.27).

P.1284

Take care to ensure that the superficialis slip is taut when the PIP joint is in 10° to 15° of flexion. Figure 39.27. One superficialis slip is fixed to the proximal phalanx, creating a tenodesis of the PIP joint.

Figure 39.27. One superficialis slip is fixed to the proximal phalanx, creating a tenodesis of the PIP joint. -

Temporarily fix the joint with a

0.035–0.045 smooth K-wire for 3 weeks, and then protect it with a

dorsal-block splint for an additional 4 weeks.

ruptures are the same as for dorsal PIP joint dislocations. Operative

repair for chronic volar plate ruptures, as for any ligament repairs or

reconstructions, can lead to some loss of motion and chronic

thickening. A flexion deformity is common.

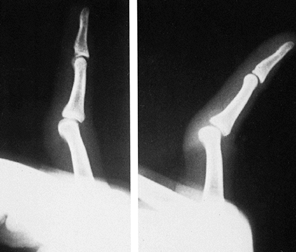

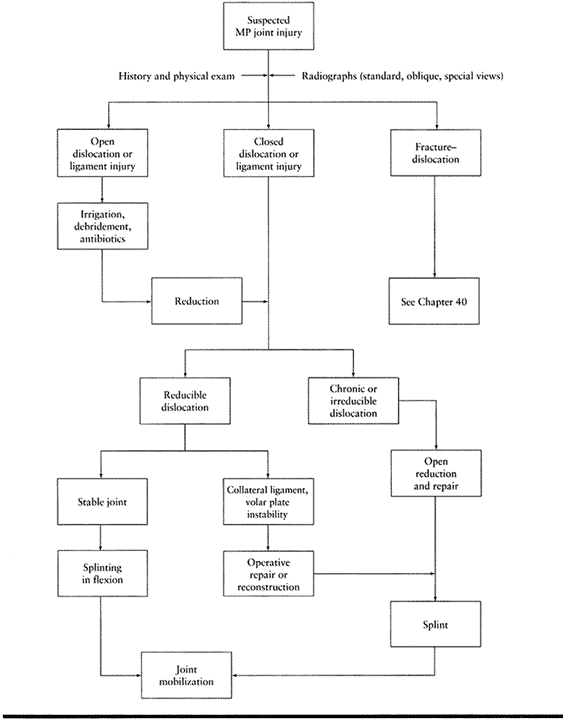

associated with an injury to the volar plate, collateral ligament, and

joint articular surface, which require adequate assessment and AP,

lateral, and oblique radiographs of the hand (Table 39.3).

A Brewerton view or oblique view of the metacarpal heads may be helpful

to identify small fractures (see the section above on General Principles of Treatment) (171,185,189,206). Open dislocations require adequate debridement and antibiotics.

|

|

Table 39.3. Algorithm for Assessment of Metacarpophalangeal (MP) Joint Injuries

|

joints are uncommon. Most of these occur with the fingers in some

extension when the collateral ligaments are more lax. This provides

some margin for protection so that complete ligament rupture is

unusual. The most common mechanism of injury is hyperextension or ulnar

deviation of the joint. The most commonly involved joint is the index

finger, followed by the thumb and little finger. Central digit

dislocations are usually associated with dislocation of either the

adjacent index or little finger (42,151,153,154,156,170,177,180,182,187,188,195,200,202,211,212,216).

dislocations or collateral ligament injuries. The dislocations are

based on the direction of the dislocation (dorsal versus volar) and

whether they are easily reducible (simple) or irreducible without

surgical intervention (complex).

membranous portion of the volar plate usually ruptures off the

metacarpal neck. Dorsal MP dislocations can be classified as simple

(subluxation) or complex dislocations (165,172,174).

Simple MP joint dislocations are easily treated by closed reduction.

Take care not to converta simple dislocation into a complex dislocation

(165,172,176,190,383).

With simple MP joint dislocations, the proximal phalanx is

hyperextended on the metacarpal head, but some contact remains between

the MP joint articular surfaces. The proximal edge of the volar plate

lies palmarward over the metacarpal head. Therefore, the base of the

proximal phalanx should be pushed distally and palmarly. If

hyperextension with traction is mistakenly used, the volar plate can

slip dorsally over the metacarpal head and prevent reduction.

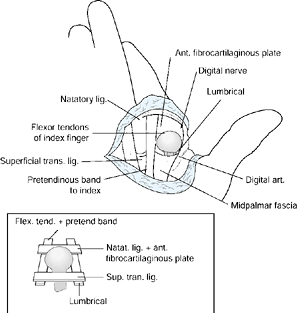

head and the base of the proximal phalanx makes this complex

dislocation irreducible (183). The lumbrical

medially and the flexor tendon laterally around the metacarpal neck

prevent reduction of the dislocation by longitudinal traction only (Fig. 39.28) (175).

With a complex dislocation of the little finger, the structures

preventing reduction include the abductor and flexor digiti minimi

ulnarly and the lumbrical and flexor tendon radially (154).

|

|

Figure 39.28.

The factors producing a complex dorsal MP joint dislocation (see text for details). (From Kaplan EB. Dorsal Dislocation of the Metacarpophalangeal Joint of the Index Finger. J Bone Joint Surg 1957;39A:1081, with permission.) |

the phalanx appearing parallel to the metacarpal with a tendency for

the digit to overlap its neighbor (Fig. 39.29).

On the palmar surface, the skin is puckered or dimpled.

Radiographically, the joint space is widened, the joint surfaces are

offset, and the sesamoid appears to lie within the joint (Fig. 39.30) (163,175,201,208).

|

|

Figure 39.29. Complex MP dislocation with the finger parallel to the metacarpal.

|

|

|

Figure 39.30. The phalanx is offset at the MP joint, lying parallel to the metacarpal in a complex dislocation.

|

-

Attempt a single effort at a closed

reduction under a good anesthetic in the operating room with the wrist

flexed to relax the flexor tendons. -

Apply pressure dorsally and distally to

the base of the proximal phalanx while attempting to slide the proximal

phalanx over the metacarpal head. -

Confirm reduction clinically and

radiographically. Assess active and passive joint stability, splint the

hand with the MP joints flexed for a few days for comfort, and start

early active motion with an extension-block splint. If a closed joint

reduction fails, perform an open reduction.

-

Make a straight or slightly curvilinear dorsal incision over the joint.

-

Longitudinally release the extensor

tendon or the sagittal band (usually on the ulnar side) and perform a

dorsal midline capsulotomy. -

Identify and carefully incise

longitudinally the volar plate in the midline; avoid damaging the

metacarpal head articular surface. Flex the wrist to relax the flexor

tendon and reduce the joint. -

If needed, push the separate halves of the volar plate over and around the metacarpal head.

-

After the joint is reduced, separately

repair the capsule, the extensor tendon or sagittal band, and the skin.

Intraoperative postreduction radiographs should confirm congruous

reduction of the joint. -

As with a closed reduction, splint the

hand with the MP joints flexed for a few days and then begin active

motion with an extension-block splint.

-

Make an incision that connects the

mid-axial line with the transverse mid-palmar crease. Take great care

to avoid injury of the digital artery and nerve (especially the

radial), which are pressed against the deep surface of the skin by the

metacarpal head. Retract the nerves and arteries gently. -

Incise the A1 pulley and retract the flexor tendons and lumbrical. The metacarpal head now dominates the field (Fig. 39.31A).

![]() Figure 39.31. A:

Figure 39.31. A:

When the skin is opened before reduction, the metacarpal head dominates

the field. The flexor tendons lie ulnarly, the lumbrical and digital

nerve radially, and the volar plate dorsally, blocking reduction. B: The volar plate (held by the forceps) has been extricated and the joint reduced. -

Carefully make a longitudinal incision

between the sides of the volar plate and the deep transverse metacarpal

ligament. Insert a sturdy but narrow-angled dental probe or skin hook

around the volar plate to extricate it from between the phalangeal base

and the metacarpal head. The joint will snap into the reduced position (Fig. 39.31B). -

Because the volar plate is still attached to the phalanx, no repair is needed.

-

Repair the skin incision and splint the

hand with the MP joints flexed for a few days. Then start active

motion, preventing MP joint hyperextension with a dorsal-block splint

for 3–4 weeks.

may result either from a delay in treatment or from overly aggressive

treatment. Damage to the articular surfaces can occur with repeated

attempts at a closed reduction or secondary to a forceful open

reduction. Traction and hyperextension of the digit can possibly

convert a simple MP joint dislocation into a complex dislocation.

occur with delayed reduction. A combined volar and dorsal approach and

collateral ligament release may be needed to openly reduce a

longstanding dislocation (165,173,174,178,186,198,213).

Injury to the neurovascular bundles can occur in the palmar approach

with an inappropriate skin incision. Redislocation can occur if

hyperextension is not prevented, and loss of joint motion can occur

with prolonged immobilization.

from the metacarpal proximally or the volar plate from the proximal phalanx, or collateral ligament avulsion, can occur (159,197,203,215).

Interposition of these structures between the metacarpal head and

proximal phalanx can occur, producing a complex dislocation (174). If an attempt at a closed reduction under adequate anesthesia is unsuccessful, an open reduction is warranted.

missed. Since the collateral ligaments of the MP joint are at their

longest or most taut in full flexion, testing for collateral ligament

stability must be performed with the joint flexed maximally. The

mechanism of injury usually consists of forced ulnar deviation of the

digits. The injury seems to occur mostly in the ulnar three fingers and

to the radial side (166,172).

Clinically, tenderness is present over the injured ligament, and stress

testing (passive radial/ulnar deviation) with the MP joint flexed

produces pain. Obtain radiographs, including oblique and Brewerton

views (171,185,189,206,213), to identify avulsion fractures. Stress views with the MP joint in full flexion may help confirm a ligament tear (213). Arthrography has been used to identify the location of the collateral ligament injury (164,181). The collateral ligament is avulsed off the metacarpal head most commonly but can also be torn distally or in midsubstance (195,196,213).

with the MP joints flexed 30° to 50° for 3 weeks, followed by taping

the finger to the adjacent digit for an additional 3 weeks (167,172,174). Surgery is advocated for gross instability of the joint (60,61,164,181,205,217),

an associated displaced avulsion fracture (displaced 2 or 3 mm), or a

displaced or rotated avulsion fracture involving 20% or more of the

articular surface (174). With persistent joint instability, late reconstruction has been advocated (164,166,178).

-

Make a longitudinal incision in the dorsum of the web space on the affected side of the digit.

-

Incise and retract the transverse fibers

of the extensor hood. Incise the joint capsule dorsal to the collateral

ligament parallel to its dorsal margin. Dissect and mobilize the

ligament. -

If there is an attached avulsion fracture

of adequate size attached to the ligament, reduce and fix the bone

fragment with one or two smooth 0.035 K-wires (Fig. 39.32). Figure 39.32. A: A displaced articular fracture usually is attached to the collateral ligament. B: K-wire fixation of the displaced fracture often must be done by placing the wire in the phalanx first.

Figure 39.32. A: A displaced articular fracture usually is attached to the collateral ligament. B: K-wire fixation of the displaced fracture often must be done by placing the wire in the phalanx first. -

Close the transverse fibers of the hood

and skin in layers and check for congruous reduction of the joint and

adequate alignment of the fracture fragment with radiographs. -

Immobilize the hand with the MP joints

flexed to 45° for 3 weeks and protected by taping the finger to the

adjacent digit for another 3 weeks.

minimally symptomatic. If they prove disabling, surgical treatment can

be difficult. The same approach as previously described is used.

Carefully tease out the collateral ligament, and mobilize it to its

maximum length. Repair the ligament to the phalanx by the pullout

suture technique. Perform closure as previously described.

ruptures are usually due to undertreatment of the injury. They include

residual pain, joint swelling, instability (index finger with pinch),

and deviated digit (abducted little finger) (166,179,186,213).

tightly (i.e., collateral ligament repair with the joint held in

extension) will result in a loss of joint motion.

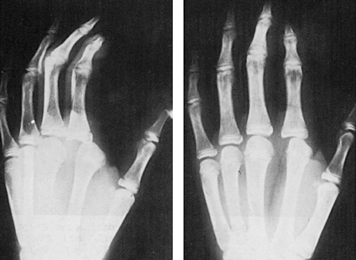

associated with intraarticular fractures, so adequate assessment of the

articular surfaces is needed with true AP, lateral, and oblique

pronated radiographs of the hand (Table 39.4).

Occasionally, tomography or a CT scan may be helpful to identify small

fractures. Open dislocations require adequate debridement and

antibiotics.

|

|

Table 39.4. Algorithm for Assessment of Carpometacarpal (CMC) Joint Injuries

|

are virtually synonymous and will be considered together. Due to the

inherent stability of the CMC joints, which are further strengthened by

strong surrounding ligaments, pure CMC joint dislocations are uncommon;

fracture–dislocations of the CMC joints are much more common.

Isolated dorsal CMC dislocations or fracture–dislocations generally

occur when a longitudinal compressive force is applied to the dorsal

aspect of the metacarpal head. This force produces a longitudinal

compressive and flexion moment to the metacarpal. Occasionally, volar

CMC dislocations can occur (218,224,228,257,265,267,277).

Multiple CMC dislocations or dislocations of the index and long CMC

joints generally occur when larger forces produce the injury. These

injuries are frequently associated with metacarpal shaft fractures and

soft-tissue injuries (219,222,227,230,231,235,237,238,242 and 243,245,246,247,248 and 249,251,252 and 253,254,257,264,268,269,273,274,275 and 276,278,279 and 280).

A 30° pronated lateral view, which places the fourth and fifth CMC

joints in profile, will help in diagnosing dislocations or

fracture–dislocations of these joints (221,232,233,250). Tomography or CT scan can be used to further delineate the injury or help diagnose occult fractures (250).

include a closed reduction, closed reduction and percutaneous K-wire

fixation, and open reduction internal fixation of the dislocation (229,236,239,244). Closed reduction is usually possible.

-

With adequate analgesia, apply

longitudinal traction to the involved digit(s). Apply pressure over the

dorsal base of the dislocated metacarpal in a distal and volar

direction, then extend the metacarpal to help reduce the dislocated

joint. Occasionally, closed reduction will fail because of interposed

soft tissues or chondral fragments. -

If the reduction is successful,

immobilize the hand with the wrist extended, the MP joints flexed, and

the IP joints extended for 3–4 weeks. -

The CMC joint(s) must be frequently

evaluated for redislocation. Because of the possibility of

redislocation, closed reduction with percutaneous pinning is preferable

(227,228 and 229,235,236,238,247,259,271). -

Transfix the metacarpal to the

appropriate carpal or an adjacent stable metacarpal. Small associated

fractures with some articular incongruity are unimportant (270).

substantial intraarticular fracture is present and remains

significantly displaced after a closed reduction, do an open reduction.

Chronic dislocations usually require open reduction and internal

fixation. Extensive dissection with excision of scar tissue may be

necessary to achieve reduction. If symptomatic posttraumatic arthrosis

is present, a resection or resection–interposition arthroplasty is

useful, and an arthrodesis remains an option (220,221,223,225,226,229,234,236,241,245,246,254,255,258,260).

-

Make a dorsal longitudinal or oblique incision over the affected joint. Protect the dorsal sensory nerve branches and veins.

-

Retract the extensor tendons and

visualize the injured joint. Retract the ruptured ligaments and debride

any small loose fragments about the joint. Gently reduce the joint. -

Reduce any intraarticular fractures and

transfix them with one or two smooth 0.035–0.045 K-wires. If no

fracture is present, reduce the dislocation and secure it with a

0.035–0.045 smooth wire placed obliquely from the metacarpal across the

joint into the appropriate carpal bone or to an adjacent stable

metacarpal. -

Ligament repair is unnecessary, although capsular closure can be performed. Confirm reduction of the joint with radiographs.

-

Close the skin and splint the hand for

3–4 weeks, allowing full finger motion after the first few days. Remove

the pins at 6 weeks.

-

Use the same approach as described for an open reduction of an acute dislocation.

-

Incise and reflect the scarred ligaments

by subperiosteal dissection. Perform an open reduction of the joint if

the joint surfaces are preserved. Confirm proper position with

radiographs. -

If arthrosis is present, resect the

proximal 1 cm of the base of the metacarpal. A tendon anchovy or a

portion of the joint capsule may be interposed in the area of the

resected metacarpal. Repair the dorsal ligaments and close the skin.

Use K-wire fixation if the joint is unstable. Splint the hand for 3–4

weeks, but permit early finger motion.

take care to preserve the transverse metacarpal arch by fusing the

fourth and fifth metacarpals in some flexion.

Undertreatment may result in a redislocation of the CMC joint following

closed reduction alone or secondary to premature removal of fixation

wires.

protecting them is imperative. Improper pinning of metacarpals to

adjacent metacarpals can lead to a “pancake” hand from flattening of

the transverse metacarpal arch. Posttraumatic arthritis can occur with

poor surgical alignment of the carpometacarpal or intermetacarpal

joints.

different from that of the other digits. Like the finger MP joint, the

thumb MP joint is a condyloid joint allowing for flexion–extension and

abduction–adduction. The amount of thumb MP joint flexion varies

widely, ranging from 5° to 115° (356). Variable amounts of MP joint hyperextension can also occur, ranging up to 45° (average 8°) (285). The amount of MP joint abduction–adduction is less in the thumb than in the fingers (0° to 20°, average 10°) (296).

A slight difference in the shape between the proximal phalangeal

condyles produces a slight amount of pronation of the thumb with MP

flexion (285,308,373).

supported by strong collateral and accessory collateral ligaments as

well as a volar plate. The adductor pollicis inserts into the ulnar

sesamoid located within the volar plate, as well as the proximal

phalanx. The abductor pollicis brevis and flexor pollicis brevis insert

into the radial sesamoid, also located within the volar plate.

Additionally, the adductor and abductor pollicis brevis tendons have an

insertion or expansion into the extensor aponeurosis (328,370,371,376).

Further support to the MP joint is provided by extensor pollicis longus

and brevis tendons associated with the dorsal MP joint capsule and the

flexor pollicis longus tendon, overlying the volar plate and sesamoids,

volarly. Stability is therefore provided by both static and dynamic

restraints.

The longitudinal axes of each joint surface are oriented perpendicular

to one another, allowing flexion–extension, abduction–adduction, and

some pronation–supination (389,390,395).

An elongated volar lip of the thumb metacarpal provides an attachment

site for the volar metacarpal ligament to the tubercle of the

trapezium. Although it has a relatively loose capsular support,

thickenings in the joint capsule help provide joint stability. Four

ligaments have been frequently cited as the main stabilizers of the CMC

joint: the volar or anterior oblique (palmar trapeziometacarpal)

ligament, the dorsal (posterior) oblique ligament, the dorsoradial

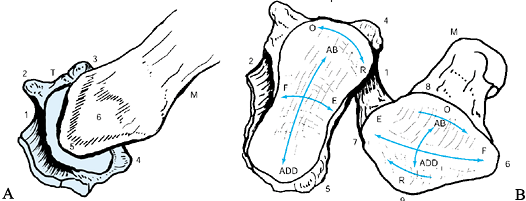

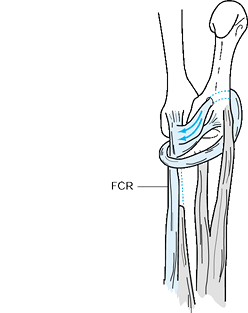

ligament, and the intermetacarpal ligament (386,387,389,392,399,402,404,406,408,409,411). Tubercles on both the metacarpal and trapezium serve as attachment sites for these ligaments (Fig. 39.33).

|

|

Figure 39.33. A: Trapeziometacarpal joint seen from the volar side. T, trapezium; M, base of first metacarpal; 1, FCR tunnel; 2, radiovolar tubercle and ridge; 3, dorsoradial tubercle; 4, dorsoulnar tubercle; 5, volar metacarpal beak; 6, volar tubercle. B: Articular facets of the trapezium (T) and first metacarpal (M). 1, dorsal ligament; 2, FCR tunnel; 3, volar radial tubercle; 4, dorsoradial tubercle; 5, dorsoulnar tubercle; 6, volar metacarpal beak; 7, dorsal beak; 8, radial or lateral tubercle; 8, ulnar or medial tubercle. (From Zancolli EA, Cozzi EP. Atlas of Surgical Anatomy of the Hand. New York: Churchill-Livingstone, 1992, with permission.)

|

to those of the MP joint of the fingers. Thumb MP joint injuries are

frequently associated with collateral ligament and volar plate

injuries, as well as an occasional intraarticular fracture.

ligament injuries, and volar plate ruptures. The dislocations are based

on the direction of dislocation of the phalanx (dorsal versus volar)

and whether they are easily reducible (simple versus complex).

The dislocation results in a complete tear of the volar plate

proximally and usually of a portion of the collateral ligaments (377). Dorsal subluxation of the MP joint can occur with less severe hyperextension injuries (324). Volar MP dislocations are not as common (313,322,344,348,349,383).

Clinically and radiographically, hyperextension of the MP joint is

noted. Widening of the joint space is suggestive of soft-tissue

interposition. Interposition of the sesamoids between the metacarpal

head and the base of the proximal phalanx is highly suggestive of a

complex MP joint dislocation.

-

Perform closed reduction of the

dislocated joint under adequate analgesia with the wrist and IP joint

flexed to relax the flexor tendon. -

Avoid longitudinal traction and

hyperextension of the thumb MP joint, and push the base of the proximal

phalanx distally and palmarly. -

Confirm congruous reduction of the joint

on radiographs and test for active and passive joint stability. Test

for collateral ligament stability and treat accordingly (see sections

below on collateral ligament ruptures). -

Occasionally, dorsal dislocations may

prove to be irreducible because of interposition of the volar plate or

other structures (e.g., sesamoid, flexor pollicis longus) between the

base of the proximal phalanx and the head of the metacarpal (296,301,310,312,323,329,341,343,354). When this situation is present, do an open reduction. Volar (323,341), dorsal (160,301), and lateral (354) approaches to the MP joint have been advocated.

-

Make a chevron-shaped incision on the

radial aspect of the joint, bringing the apex of the incision somewhat

palmarly. Take care to not injure the digital nerves, especially the

radial. -

Partially release the proximal flexor tendon pulley and retract the flexor pollicis longus.

-

Make a longitudinal incision between the

radial collateral ligament and the edge of the volar plate. Place a

stiff-angled probe or a skin hook behind the volar plate, extricate it

from the joint, and allow the joint to reduce. -

Repair the ligament, if needed, either directly or using pullout suture technique.

-

Close the skin. Confirm congruous

reduction of the joint with radiographs. After initial immobilization

for comfort for a few days, begin motion using an extension-block

splint for 3–4 weeks.

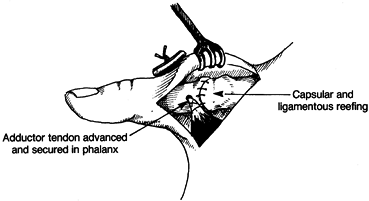

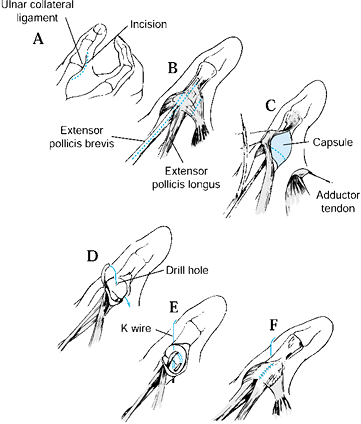

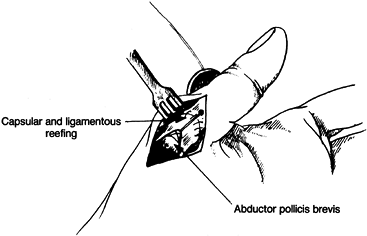

referred to as gamekeeper’s thumb and skier’s thumb, are common

injuries (289,295,296,304,305,325,343,345,346,351,368,371,385).