CHAPTER 43 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 43 – Arthroscopic Meniscectomy

Christopher Kaeding, MD

Tears of the meniscus have been known to cause pain and mechanical symptoms of the knee. Historically, open meniscectomy has been shown to lead to the development of progressive radiographic signs (Fairbank changes) of osteoarthritis in the meniscus-deficient compartment. With the advent of arthroscopy, partial, subtotal, or total meniscectomy can be performed with minimal incisions and on an outpatient basis. In fact, arthroscopic meniscectomy is the most commonly performed orthopedic procedure in the United States. Despite the minimally invasive nature of arthroscopy and its faster recovery, radiographic changes can still be seen with partial meniscectomies because of the increased articular contact pressures. The goal of arthroscopic meniscectomy today is to remove as little meniscal tissue as possible to achieve a pain-free, stable meniscus.

Patients typically recall an acute sudden twisting mechanism that caused the onset of pain. Degenerative tears may be more subacute in nature and subtle in onset with underlying arthritic or baseline pain that has now become localized and sharp. A detailed history of previous knee pain, previous surgeries in the knee, and other injuries (ligament injury, fracture) should be elicited.

A thorough knee examination is crucial because meniscal tears are commonly associated with other injuries, such as anterior cruciate ligament injuries and tibial plateau fractures. A detailed knee examination has been consistently shown to be reliable in diagnosis of a meniscal tear.

Specific findings for meniscal tears may include the following:

Baseline plain radiography is of limited importance for diagnosis of meniscal disorders but is necessary to rule out other pathologic processes, such as stress fracture, avascular necrosis, tumor, and arthritis, that may mimic meniscal signs and symptoms. Standard radiographs include a 45-degree flexed posteroanterior view, weight-bearing anteroposterior view, lateral view, and Merchant view.

Magnetic resonance imaging is not a substitute for a good examination, but it can be a useful tool to confirm the diagnosis or to differentiate pathologic changes in difficult cases. Meniscal tears on magnetic resonance imaging are described as abnormal meniscal signal that extends to the articular surface of the meniscus (grade 3 meniscal signal). Numerous studies have shown that the accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging is 95% or greater for meniscal tears.

Arthroscopic evaluation has aided in the classification of meniscal tears. Meniscal tears can be classified by vascular zone or tear patterns. Both classifications are often used in determining whether a tear is favorable for repair.

Arnoczky and Warren[2] reported on the vascularity of the meniscus, which is divided into three zones: red-red (peripheral 25% to 33%), red-white, and white-white (central 33%). Healing has been found to be more favorable in the vascular zones (i.e., red-red and red-white).

Meniscal tears are commonly described by tear pattern. Examples of common tear patterns are illustrated in

Figure 43-1

.

|

|

|

|

Figure 43-1 |

Indications and Contraindications

Meniscectomy is indicated for any symptomatic meniscal tear that is abnormally mobile or not conducive to repair and has failed conservative measures.

Contraindications are active septic arthritis and significant medical comorbidities.

Multiple manufacturers have produced meniscal baskets, biters, graspers, scissors, and arthroscopic shavers. Common instruments needed for arthroscopic meniscectomy are illustrated in

Figure 43-2

. These include the following:

| • | Meniscal biters or baskets: straight, up-going, 90-degree right and left, backbiting | |

| • | Meniscal scissors | |

| • | Meniscal grasper | |

| • | Arthroscopic shaver: 3.5- to 4.5-mm full radius |

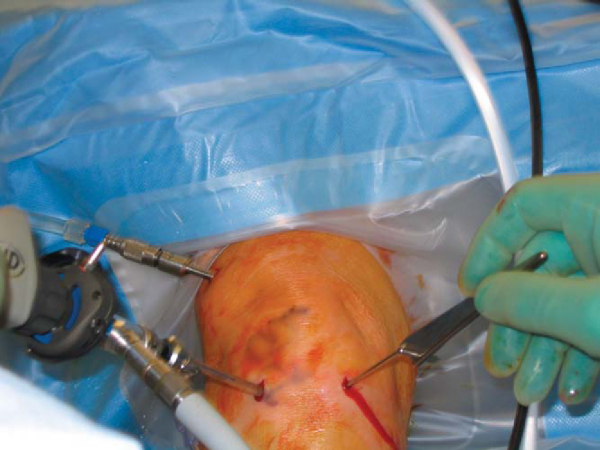

The operative leg is marked in the holding area, and preoperative antibiotics are administered 30 minutes before the case is begun. The procedure can be performed under general, regional, spinal, or, in some cases, local anesthesia. The patient is positioned supine with all bone prominences well padded; a tourniquet is placed high on the operative thigh, and the leg is positioned in a standard leg holder. The nonoperative leg is placed in the lithotomy position, well padded. The foot of the table is then flexed down, allowing full flexion of the operative leg. The leg is prepared and draped in a standard fashion (

Fig. 43-3

). The tourniquet can be inflated per the surgeon’s preference.

|

|

|

|

Figure 43-3 |

Portals (

Fig. 43-4

)

|

|

|

|

Figure 43-4 |

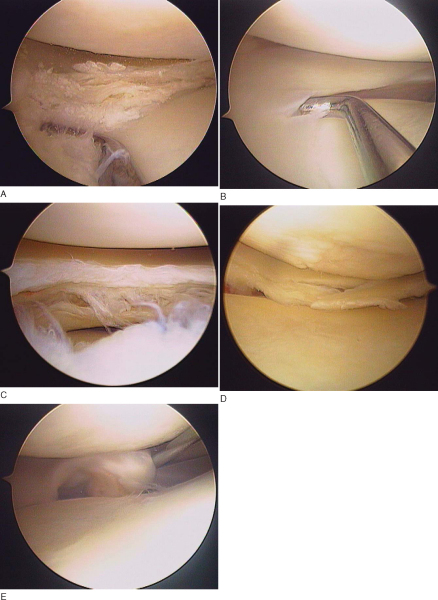

A thorough arthroscopic evaluation of the knee is performed. The meniscus should be visually inspected and probed to determine the zone of the tear, the pattern of the tear, the length of the tear, and whether it is stable or unstable. Flipped meniscal segments or bucket-handle tears should be reduced for meniscal evaluation.

At times, placement of the scope through the notch is necessary to determine the extent of the tear at its posterior horn or to visualize any flipped segment or loose piece posteriorly (

Fig. 43-5

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 43-5 |

Arthroscopic Meniscectomy (

Box 43-1

)

The goal is to saucerize the tear from the native meniscus. With use of the meniscal scissors or basket, gradually start to remove normal meniscal tissue and taper it toward the apex of the tear. It is important to move arthroscopic instruments in a controlled fashion to minimize iatrogenic cartilage damage. Care should be taken to keep the meniscal basket in contact with the meniscus at all times to allow consistency of meniscal tissue removal. To ensure a smooth transition, the anterior aspect of the tear may require resection with a 90-degree basket if the ipsilateral portal is used or a straight basket if the contralateral portal is used. An arthroscopic shaver can smooth any edges.

Bucket-handle tears that are irreparable because of tissue quality, deformation, or zone of injury should first be reduced to assess the length of the tear. Visualization of the extent of the posterior aspect of the tear may be improved by assessing the meniscus through the notch. Appropriate planning to truncate the posterior attachment without leaving an abrupt edge is needed. This may require rotation of the meniscal basket or scissors more centrally and posteriorly to make a proper transition to the tear. It is typically easier to remove most of the posterior attachment first, leaving just a few strands of tissue that can easily be torn by rotating the meniscus for removal. This will prevent the meniscus from becoming a loose body when the anterior aspect is removed. The anterior aspect of the tear can then be addressed through the ipsilateral or contralateral portal as discussed before. After the ipsilateral portal is enlarged with a hemostat, a grasper can be used to firmly grab the meniscus. Enlargement of the portal by several millimeters is often needed to ensure that the resected fragment is not dislodged from the grasper during extraction. Rotation of the meniscus should avulse the remaining strands of the posterior meniscus, and the meniscus can be removed en bloc through the portal. Care must be taken not to allow the resected fragment to become a loose body. A meniscal shaver can smooth any edges as necessary. Alternatively, for small bucket-handle tears, the anterior edge can be removed as detailed before, and the meniscal shaver can débride the meniscus to its posterior base.

Controversy still exists about how to properly approach a horizontal cleavage tear. Options include removal of the most unstable leaf (superior or inferior) and removal of both leaves of the tear. Cleavage tears often make a flap on one of the leaflets that causes pain and mechanical symptoms. Although horizontal cleavage tears typically extend to the peripheral margin, it is not necessary to remove all of the meniscal tissue to make a stable tear and smooth transition.

Our bias is to remove the most unstable leaf, retaining part of the meniscus for function. The approach is similar to removal of a bucket-handle tear. The majority of the posterior attachment is removed through the ipsilateral portal, then the anterior attachment is removed through the contralateral portal. Finally, by use of a basket or meniscal scissors, the peripheral attachment is resected, leaving some pericapsular meniscal tissue. The leaf is removed either en bloc with the grasper or piecemeal with a shaver. The arthroscopic shaver is used to smooth any edges, but care must be taken with the thinned meniscus as the shaver may aggressively remove the tissue that is to be preserved.

Meniscal cysts are common findings that typically indicate intraarticular disease. Meniscal tears commonly make a rent in the capsular tissue and a one-way valve occurs, allowing synovial fluid to collect extra-articularly. Lateral meniscal cysts are located off the lateral joint line associated with a midportion lateral meniscus tear. Posterior medial cysts (Baker cyst) commonly associated with a posterior medial meniscus tear dissect between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the semimembranosus. The meniscal cyst is often decompressed with treatment of the intraarticular meniscal tear. Commonly, with a lateral meniscal cyst, a spinal needle can be entered percutaneously at the lateral joint line level through the meniscal tear to aid in its decompression.

Patients are seen at 1 week postoperatively for wound check and suture removal. Subsequent followup is scheduled for 1 month postoperatively for evaluation of knee symptoms, range of motion, and strength.

Goals are to reduce pain, inflammation, and swelling and to restore motion and strength. This can typically be accomplished with a home exercise program. Formal physical therapy can assist older patients. A standard protocol consists of the following:

| • | Crutches for 24 to 72 hours, as needed | |

| • | Ice for 20 minutes, three to six times a day | |

| • | Immediate progression of unrestricted range-of-motion exercises (passive, active-assisted, and active), quadriceps exercises, straight-leg raises | |

| • | No impact activities for 4 weeks | |

| • | Return to play with no inflammation, full motion, and 80% of strength of contralateral extremity |

| • | Infection | |

| • | Deep venous thrombosis | |

| • | Arthrofibrosis | |

| • | Portal herniation or fistula | |

| • | Neuroma at portal site | |

| • | Retained meniscal fragment (loose body) | |

| • | Repeated tear of meniscus | |

| • | Continued pain in the compartment (chondral erosions) |

Results of studies of arthroscopic meniscectomy are shown in

Table 43-1

.

| Author | Medial or Lateral | Type of Tear | Followup (Years) | Results | Symptoms | Radiographic Changes | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chatain et al[7] (2003) | Both | Mix | 10 | 95% satisfied | 14% medial 20% lateral | 22% medial 38% lateral | Better prognosis with medial tears, age <35 years, vertical tear, no cartilage damage, intact peripheral rim |

| Hulet et al[10] (2004) | Lateral with cyst | Mix (57% horizontal cleavage) | 5 | 87% good– excellent | 9% | ||

| Pearse et al[15] (2003) | Both | Mix (degenerative) | 1 | 65% improvement | Preexisting severe OA | At 4 years, 32% with further surgery | |

| Bonneux and Vandekerckhove[5] (2002) | Lateral | Mix | 8 | 64.5% good– excellent | 93% | Amount or resection correlates with results | |

| Menetrey et al[14] (2002) | Medial | Mix | 3-7 | 90% NDM 20% DM |

NDM, DM | ||

| Andersson-Molina et al[1] (2002) | Both | Mix | 14 | 70% | 14% | 33% partial meniscectomy 72% total meniscectomy |

|

| Scheller et al[16] (2001) | Lateral | Mix | 10 | 77% | 78% | Results decrease over time | |

| Crevoisier et al[8] (2001) | Both | Degenerative, mix | 4 | 80% satisfied 55% satisfied |

Grade 0-2 OA Grade 3-4 OA |

Age >70 years | |

| Hoser et al[9] (2001) | Lateral | Mix | 10 | 58% good– excellent | 95% | 29% reoperation | |

| Hulet et al[11] (2001) | Medial | 95% vertical 5% complex |

12 | 95% very satisfied– satisfied | 16% | ||

| Kruger-Franke et al[12] (1999) | Medial | Mix | 7 | 96% | 33% | Women at greater risk of degenerative changes | |

| Barrett et al[3] (1998) | Lateral | Mix | 3 | 94%, 80% improvement | Grade 0-2 Grade 3-4 | 14% failure | |

| Schimmer et al[17] (1998) | Both | Mix | 4, 12 | 92%, 78% good– excellent | Worse at 5 years if cartilage damage | Underlying cartilage damage faired worse | |

| Burks et al[6] (1997) | 78% medial 19%lateral |

Mix | 14 | 88% good– excellent | No difference medial vs. lateral; ACL-deficient and female patients did worse | ||

| Matsusue and Thomson[13] (1996) | Medial | Mix | 7.8 | 83% good– excellent | Worse outcomes with grade 3-4 OA | ||

| Bonamo et al[4] (1992) | Both | Mix | 3 | 83% satisfied | Preexisting grade 3-4 | Worse outcomes with women, age >60 years, grade 4 changes |

|

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; DM, degenerative meniscus; NDM, nondegenerative meniscus; OA, osteoarthritis. |