CHAPTER 40 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 40 – Open Treatment of Lateral and Medial Epicondylitis

Robert J. Goitz, MD

Elbow injuries in the athlete are common entities. Most of these injuries are secondary to repetitive or overuse activities. The sports-related variety of lateral epicondylitis is usually associated with racket sports. It occurs four to five times more frequently in men than in women and more frequently in the dominant arm. In this group of patients, abnormal stresses are placed across the wrist extensor origin and are thought to lead to pathologic changes within the muscle and tendon. Most commonly, the pathologic change associated with lateral epicondylitis arises in the region of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB). The pain is thought to originate from tendon degeneration and incomplete healing.

Numerous studies have reported 75% to 90% cure rates with a sufficient trial of nonoperative therapy. Initial treatment of lateral epicondylitis begins with activity modification. Patients are instructed to avoid lifting with the wrist extended and to lift objects with the elbow in flexion as close to the body as possible with the hand in supination or neutral position to avoid applying stresses to the wrist extensor muscles. Patients who actively participate in racket sports should consider rackets with better shock absorption and consult with their instructor on optimal mechanics to minimize persistent problems. Conservative treatment also includes physical therapy focusing initially on stretching and progressive light strengthening of the forearm wrist extensors. Orthotics, such as the counterforce brace (tennis elbow strap), and nighttime wrist extension splinting have proved to be supportive, especially in controlling pain. If a combination of physical therapy and bracing is unsuccessful, a local cortisone injection may be attempted. However, if nonoperative treatment for a period of 6 to 12 months fails, operative treatment is indicated for persistent pain and disability.

Many techniques have been described for release of the ECRB, including open, percutaneous, and arthroscopic approaches. Recent research has shown no significant difference in outcomes between open release and arthroscopic release. The authors prefer open excision of the pathologic portion of the ECRB tendon, stimulation of bleeding bone, and repair of the defect, given the reproducibility of the postoperative results and relative straightforwardness of the procedure.

History and Physical Examination

Evaluation of the athlete with lateral elbow pain begins with a thorough history. The history focuses on types of racket sports as well as any recent changes in equipment. A history of repetitive activity or overuse can often be elicited.

Athletes typically present with lateral elbow pain and decreased grip strength. The pain may extend into the dorsal forearm. Symptoms are exacerbated by activities involving wrist extension against gravity. During the physical examination, pain is elicited with palpation over the lateral epicondyle or slightly distal and anterior to the epicondyle. Pain is exacerbated with resisted wrist extension and long finger extension because of the ECRB origin from the base of the middle finger metacarpal.

| • | Standard radiographs of elbow (anteroposterior, lateral, oblique) |

Evaluate for calcifications, osteochondral defect, exostosis, and degenerative changes of the radiocapitellar joint.

The best candidate for operative intervention has had 6 to 12 months of conservative treatment, including bracing, physical therapy, and cortisone injections. Other causes of lateral elbow pain, such as radial tunnel syndrome, should be excluded. Results after surgical intervention reveal that 85% to 90% of patients who undergo débridement of the ECRB and repair technique return to full activity without pain.

Several surgical techniques have been described for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Surgical treatment ranges from resection of the epicondyle to percutaneous or open division of the common extensor origin to tendon lengthening techniques. The most common technique involves identification and excision of the abnormal ECRB origin with creation of a vascular bone bed to promote healing.

The authors prefer open excision of the pathologic portion of the ECRB tendon, stimulation of bleeding bone, and repair of the defect for initial surgical management. Retrospective results have revealed high success rates, with 80% to 90% of patients having good and excellent results.

On the basis of the surgeon’s and anesthesiologist’s preferences, the procedure can be performed under regional axillary block, Bier block, or local with sedation. However, tourniquet pain may become difficult for the patient to tolerate if the procedure takes more than 10 or 15 minutes. The patient is positioned supine on the operating room table with the arm on a standard hand table. A nonsterile tourniquet is placed around the upper arm.

Surgical Landmarks and Incisions

| • | Lateral epicondyle | |

| • | Radial head | |

| • | Olecranon |

| • | Centered slightly anterior to lateral epicondyle | |

| • | Extend 1 cm above the lateral epicondyle to 2 or 3 cm distally toward the radial head |

Specific Steps (

Box 40-1

)

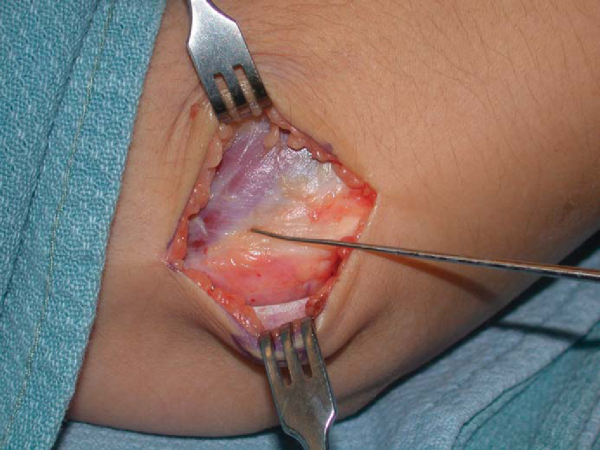

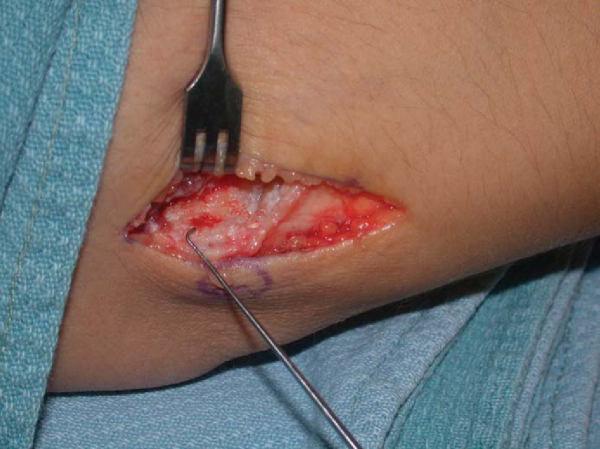

The skin incision is marked slightly anterior to the lateral epicondyle (

Fig. 40-1

) in a curvilinear pattern. Important landmarks to be outlined are the lateral epicondyle, radial head, and olecranon. Thick skin flaps are developed sharply down to the fascial layer. Typically, no significant cutaneous nerves are present in this area because it is a watershed region between the posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve and the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve (

Fig. 40-2

).

| Surgical Steps | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 40-2 |

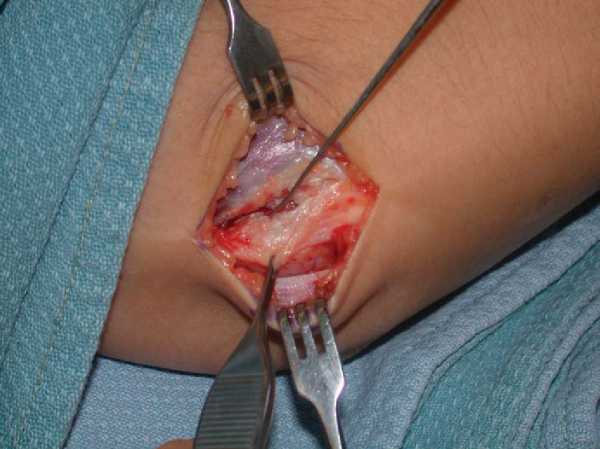

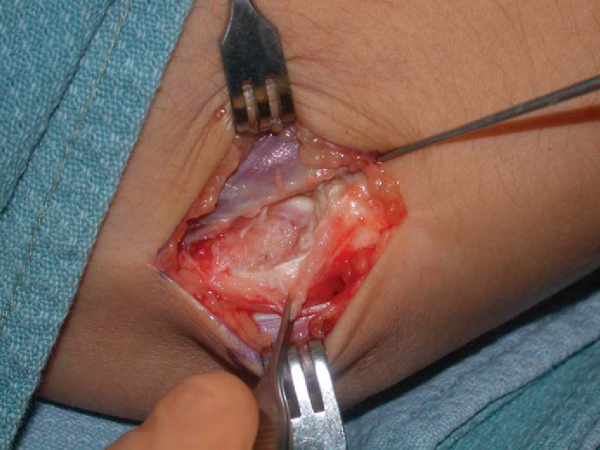

The ECRB is identified by locating the interval between the muscle and tendon at the lateral epicondyle. The tendinous edge marks the overlapping extensor digitorum communis and underlying ECRB (

Fig. 40-3

). Sharply incise the fascia between the extensor carpi radialis longus and extensor digitorum communis aponeurosis. Expose the ECRB origin below the extensor digitorum communis. The ECRB is often friable and amorphic, lacking the longitudinal fibers of the normal adjacent tendon.

|

|

|

|

Figure 40-3 |

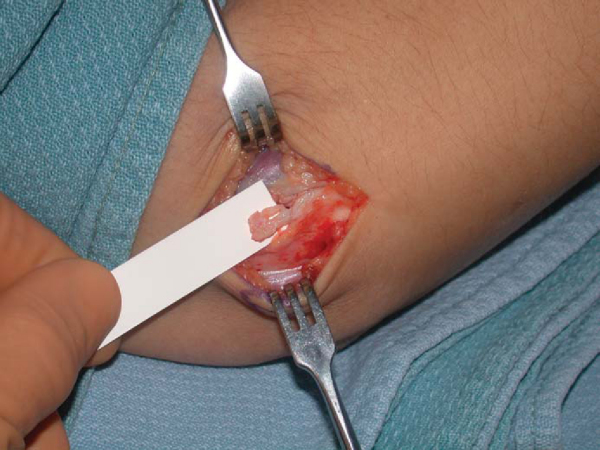

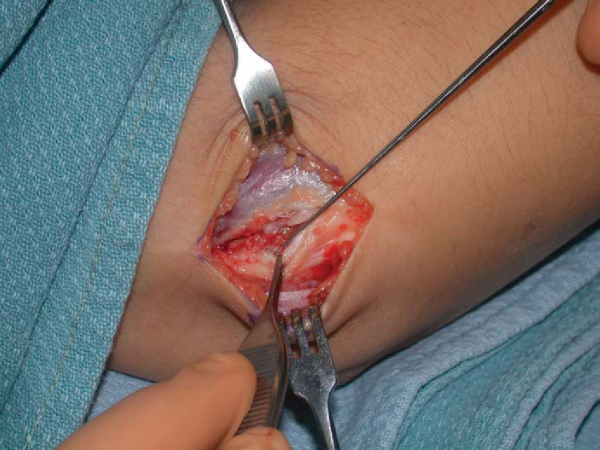

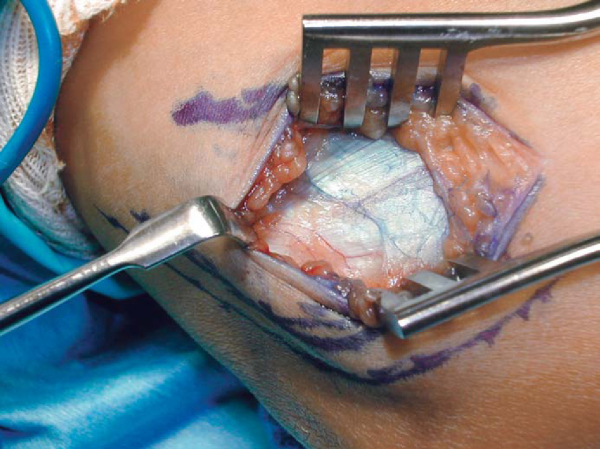

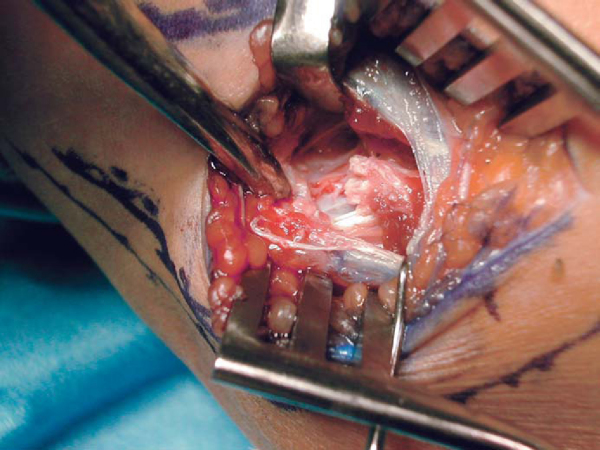

The degenerated tendon is identified and then sharply débrided (Figs. 40-4 to 40-6 [4] [5] [6]). To avoid injury to the lateral collateral ligament, stay anterior to the epicondyle. The lateral collateral ligament originates on the distal portion of the epicondyle. Once the tendon is adequately débrided, a rongeur or curet is used to decorticate the lateral epicondyle and enhance blood supply to the tendon (

Fig. 40-7

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 40-6 |

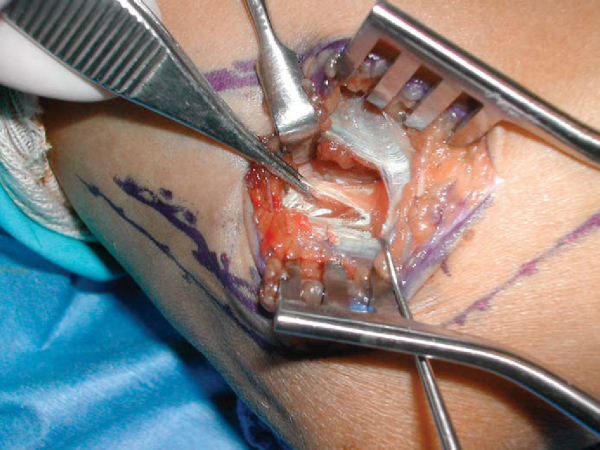

After adequate débridement, the capitellum may be partially visible (

Fig. 40-8

). Close the capsule to prevent fistula formation. A side-to-side repair of the extensor mechanism is achieved with interrupted 2-0 absorbable sutures.

The wound is copiously irrigated with antibiotic solution. The tourniquet is released, and adequate hemostasis is achieved. The subcutaneous tissues are closed with an absorbable suture, and the skin is closed with a 4-0 subcuticular stitch. The patient’s elbow is then placed into a soft dressing.

At 10 to 14 days postoperatively, the soft dressing is taken down and the wound is checked.

| • | 2 weeks: Active range-of-motion exercises are begun for the elbow, wrist, and forearm; progressive passive range of motion is instituted as necessary. | |

| • | 6 weeks: Gentle strengthening begins with light repetition. Gentle strokes are allowed for racket athletes. | |

| • | 3 months: Increased strengthening exercises are initiated. Return to competitive sports is permitted once strength has returned to 85% that of the contralateral upper extremity. |

| • | Elbow instability secondary to excessive resection of lateral collateral ligament | |

| • | Joint fistula formation |

The results of surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis are shown in

Table 40-1

.

| Author | Followup | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Nirschl and Pettrone[5] (1979) | 6 years | 85% complete relief of symptoms and no activity restrictions |

| Goldberg et al[3] (1988) | 4 years | 91% good and excellent results |

| Organ et al[6] (1997) | 64 months | 83% good to excellent results |

| Rosenberg and Henderson[7] (2002) | 2 years | 95% satisfactory results |

| Dunkow et al[2] (2004) | 12 months | 92% very pleased or satisfied (open technique) |

| 100% very pleased or satisfied (percutaneous technique) | ||

| Coleman and Matheson[1] (2005) | 9.8 years | 97% good to excellent results |

Medial epicondylitis is much less frequent than lateral epicondylitis. Medial epicondylitis is also associated with sports overuse activities. This disorder is an injury affecting many athletes at all levels, especially throwing athletes. Medial epicondylitis is also known as golfer’s elbow and pitcher’s elbow. The primary etiology of medial epicondylitis is an overuse syndrome of the flexor-pronator mass. The pronator teres and flexor carpi radialis are most commonly involved. The pathophysiologic process of medial epicondylitis represents a microtearing of the medial tendon and ligaments. Pain is the main presenting symptom; however, the athlete may also present with ulnar nerve symptoms of numbness and tingling in the small and ring fingers. The pain is localized to the medial aspect of the elbow. On occasion, pain may be distal to the medial epicondyle and radiate into the flexor-pronator mass. Activities that require pronation and flexion of the elbow and wrist exacerbate symptoms.

Nonoperative treatment begins with activity modification. Some racket athletes may need to adjust their racket grip, often to a larger size. Athletes are encouraged to avoid constant activities that require pushing the hand with the forearm in pronation. Athletes are also educated in proper warm-up technique and conditioning. Anti-inflammatories, stretching, and counterforce bracing may also be helpful. Anti-inflammatory medication is administered for a period of 10 to 14 days. Local steroid injections are indicated in refractory cases of medial epicondylitis. The steroid is injected deep to the flexor-pronator mass to minimize subcutaneous atrophy and hypopigmentation. When the athlete does not respond to conservative treatment for a period of 6 to 12 months, operative intervention is discussed. Open surgical release of the flexor-pronator origin remains the mainstay of operative treatment.

History and Physical Examination

The diagnosis of medial epicondylitis requires a thorough history and physical examination. Athletes present with tenderness over the medial epicondyle and pain with resisted pronation or wrist flexion. On occasion, the pain may radiate into the forearm. Athletes usually will present with a full range of motion at the elbow; however, they should be monitored for development of a flexion contracture. The findings on neurovascular examination are usually normal.

It is important to differentiate between ulnar neuropathy (cubital tunnel syndrome), ulnar collateral ligament instability, and medial epicondylitis. Ulnar neuropathy usually presents with a Tinel sign or positive elbow flexion test result on physical examination, which produces numbness and tingling in the ring and small fingers. Ulnar collateral ligament instability is confirmed with a positive result of the valgus stress test at 30 degrees of elbow flexion.

Radiographs are usually normal but should be obtained to check for calcification of the flexor-pronator mass or evidence of previous injury to the medial epicondyle, such as an avulsion. Calcification may suggest a previous injury to the ulnar collateral ligament.

| • | Point tenderness at medial epicondyle | |

| • | Pain exacerbated with resisted wrist flexion and pronation | |

| • | Tinel sign and compression test at elbow | |

| • | Evaluate for ulnar nerve subluxation |

| • | Standard radiographs of elbow (anteroposterior, lateral, oblique) |

Evaluate for medial ulnohumeral osteophytes, medial collateral ligament calcification, and evidence of previous injury to the medial epicondyle, such as a malunited avulsion fracture.

| • | Cases that have failed nonoperative treatment for 6 to 12 months | |

| • | Exclusion of other pathologic causes of medial-sided elbow pain | |

| • | Temporary relief after steroid injection |

Surgical treatment of medial epicondylitis is not as well understood as that of lateral epicondylitis. Procedures for medial epicondylitis range from percutaneous epicondylar release to epicondylectomy. Most have agreed that standard surgical treatment of medial epicondylitis involves excision of the pathologic portion of the tendon and repair of the defect, similar to treatment of lateral epicondylitis.

| • | Regional axillary or Bier block anesthesia | |

| • | Patient supine on operating room table with upper arm on a hand table | |

| • | Nonsterile upper arm tourniquet |

Surgical Landmarks and Incisions

| • | Medial epicondyle | |

| • | Flexor-pronator mass | |

| • | Ulnar nerve |

| • | Gently curved 3- to 4-cm incision along medial epicondyle |

Specific Steps (

Box 40-2

)

The patient is placed supine on a standard operating room table with the arm on an arm board. A nonsterile tourniquet is placed on the upper arm. The arm is exsanguinated with an Esmarch band, and the tourniquet is inflated. A 3- to 4-cm oblique skin incision is made just anterior to the medial epicondyle, and the dissection is carried down through the subcutaneous tissue (

Fig. 40-9

).

| Surgical Steps | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Thick skin flaps are developed down to the flexor-pronator origin. Branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, which are typically 1 inch distal to the medial epicondyle, should be identified and protected during this part of the surgical exposure (

Fig. 40-10

).

The anterior skin flap is mobilized, and the flexor-pronator mass is identified. The ulnar nerve is identified and protected throughout the case. Once the common flexor origin is identified, the fascial interval between the flexor carpi radialis and pronator teres is sharply incised (

Fig. 40-11

).

The degenerative tissue on the undersurface of the flexor-pronator mass is identified and débrided (

Fig. 40-12

). Deep to the flexor-pronator mass lies the ulnar collateral ligament. Special attention should be given to protection of the medial collateral ligament during débridement. A rongeur or rasp is used to decorticate the medial epicondyle and create a vascular bed (

Fig. 40-13

).

The common flexor-pronator mass is repaired with an absorbable 2-0 suture (

Fig. 40-14

). The subcutaneous tissues are closed with 4-0 absorbable suture, and skin is closed with a 4-0 subcuticular suture. The patient is placed into a well-padded sterile dressing. A posterior splint may be used if the patient was particularly uncomfortable preoperatively.

| PEARLS AND PITFALLS | |||||||||

|

The dressings are removed 10 to 14 days postoperatively.

| • | Days 10-14: Gentle active range-of-motion exercises are begun for the elbow as well as for the wrist and hand, followed by progressive passive range of motion. A stretching program is resumed. | |

| • | 4-6 weeks: Strengthening program starts. | |

| • | 12 weeks: Return to play is permitted once strength is 85% that of the contralateral extremity. |

| • | Residual pain | |

| • | Valgus instability | |

| • | Unaddressed cubital tunnel syndrome | |

| • | Hypoesthesia along proximal forearm | |

| • | Medial antebrachial cutaneous neuroma |

The results of operative treatment of medial epicondylitis are shown in

Table 40-2

.

| Author | Followup | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Vangsness and Jobe[8] (1991) | 6 years | 97% good to excellent results |

| Wittenberg et al[9] (1992) | 4 years, 9 months | 82% good to excellent results |

| Gable and Morrey[3] (1995) | 7 years | 87% good to excellent results |

1.

Coleman B, Matheson J: Surgical treatment of resistant lateral epicondylitis: a long-term followup.

J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005; 87(suppl III):335-336.

2.

Dunkow PD, Jatti M, Muddu BN: A comparison of open and percutaneous techniques in the surgical treatment of tennis elbow.

J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004; 86:701-704.

3.

Gabel GT, Morrey BF: Operative treatment of medial epicondylitis: the influence of concomitant ulnar neuropathy at the elbow.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995; 77:1065-1069.

4.

Goldberg EJ, Abraham E, Siegel I: The surgical treatment of chronic lateral humeral epicondylitis by common extensor release.

Clin Orthop 1988; 233:208-212.

5.

Nirschl RP, Pettrone FA: Tennis elbow: the surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1979; 61:832-839.

6.

Organ SW, Nirschl RP, Kraushaar BS, et al: Salvage surgery for lateral tennis elbow.

Am J Sports Med 1997; 25:746-750.

7.

Rosenberg N, Henderson I: Surgical treatment of resistant lateral epicondylitis. Followup study of 19 patients after excision, release and repair of proximal common extensor tendon origin.

Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2002; 122:514-517.

8.

Vangsness C, Jobe FW: Surgical treatment of medial epicondylitis: results in 35 elbows.

J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991; 73:409-411.

9.

Wittenberg RH, Schaal S, Muhr G: Surgical treatment of persistent elbow epicondylitis.

Clin Orthop 1992; 278:73-80.

Barrington and Hage, 2003.

Barrington J, Hage WD: Lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow): nonoperative, open or arthroscopic treatment?.

Curr Opin Orthop 2003; 14:291-295.

Baumgard and Schwartz, 1982.

Baumgard SH, Schwartz DR: Percutaneous release of epicondylar muscles for humeral epicondylitis.

Am J Sports Med 1982; 10:233-236.

Ciccotti and Ramani, 2003.

Ciccotti MG, Ramani MN: Medial epicondylitis.

Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg 2003; 7:190-196.

Cohen and Romeo, 2001.

Cohen MS, Romeo AA: Lateral epicondylitis: open and arthroscopic treatment.

J Am Soc Surg Hand 2001; 1:172-176.

Jobe and Ciccotti, 1994.

Jobe FW, Ciccotti MG: Lateral and medial epicondylitis of the elbow.

J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1994; 2:1-8.

Kaminsky and Baker, 2003.

Kaminsky SB, Baker CL: Lateral epicondylitis of the elbow.

Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg 2003; 7:179-189.

Peart et al., 2004.

Peart RE, Strickler SS, Schweitzer KM: Lateral epicondylitis: a comparative study of open and arthroscopic lateral release.

Am J Orthop 2004; 33:565-567.