CHAPTER 35 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 35 – Elbow Arthroscopy for the Arthritic Elbow

Scott P. Steinmann, MD

The indications for and thus the number of procedures that can be performed by arthroscopy of the elbow joint have increased recently. Initially used for loose body removal or examination of a painful joint, arthroscopy is performed to treat many of the pathologic changes encountered with osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, and posttraumatic conditions. [11] [12]

Elbow arthroscopy is technically challenging because of the small working space and the exclusive anatomy of the multiple articulations that make up the elbow. Potential advantages include improved articular visualization, decreased postoperative pain, and faster postoperative recovery. The immediacy of the major neurovascular structures is the greatest concern of most orthopedic surgeons.

The goal of this chapter is to introduce the common findings of arthritic conditions of the elbow while providing the technical steps and pearls for treatment of the unique aspects of these conditions.

Posttraumatic arthritis, osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis may affect the elbow joint. Pain is the most common complaint; however, patients may also complain of stiffness, weakness, instability, or cosmetic deformity.[7] A subjective description of the amount of motion loss and pain is an important part of the history. It is imperative to elucidate a history of trauma from patients. The most common injury that may cause posttraumatic arthritis is a comminuted intraarticular distal humerus fracture resulting in articular incongruity.[7] Posttraumatic contractures solely due to capsular fibrosis are secondary to hemarthrosis from various traumatic causes. The patient should be asked whether he or she had physical therapy, whether it was painful or relatively benign, and whether splints had been used for short- or long-term sessions.

Osteoarthritis involving the elbow is most commonly seen in men with a history of heavy labor using the arm, weight lifters, and throwing athletes.[7] They commonly present in the third to eighth decades. Patients typically complain of pain at extremes of motion with loss of terminal extension more than loss of flexion. Patients with osteoarthritis primarily do not have pain in the mid-arc of motion. Rheumatoid arthritis affects the elbow less commonly than other joints but can be quite debilitating when it does occur. Both elbows are commonly involved. Patients initially present with pain and swelling due to synovitis and effusion. Rheumatoid arthritis predominantly involves the ulnohumeral articulation. More severe involvement with loss of bone stock and failure of the soft tissues around the elbow joint may cause instability, which may increase articular destruction as a result of subluxation or malalignment.

On examination, patients will have pain at the endpoints of motion. A flexion contracture of 30 degrees is common along with loss of flexion. Crepitus may also be present. It is important to record the passive and active ranges of motion. This aids in quantifying the functional deficits while determining the success of treatment. Although difficult, it may be useful to differentiate between a “soft” and “hard” endpoint as this may lead the examiner to determine the cause of stiffness. A complete neurovascular examination should always be performed. The physical examination findings are then correlated with the radiographic findings.

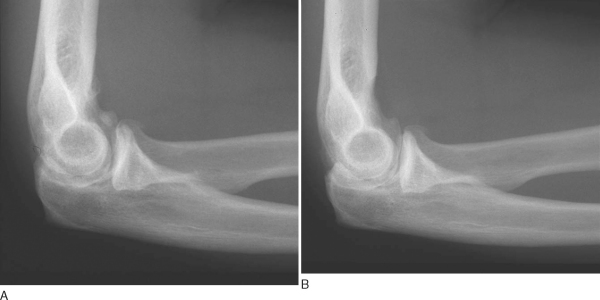

Anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique views of the elbow should be obtained. On radiographic examination, osteophytes may be seen on the olecranon and coronoid processes and also in the olecranon and coronoid fossae. Most patients have loose bodies as a result of progressive degenerative arthritis. The presence of a loose body on an elbow radiograph is in most instances the sign of underlying degenerative arthritis.

Computed tomography, particularly three-dimensional reformatting, may be helpful for visualizing impinging osteophytes and malunions.

Surgery in an elbow with arthritis is indicated for patients with functional loss of motion and pain accompanied by osteophyte formation, loose bodies, and capsular contraction.

We prefer to use general anesthesia. This allows full muscle relaxation and permits the patient to be placed in either a prone or a lateral decubitus position, which might not be tolerated by an awake patient. Regional anesthetic blocks can be administered for elbow arthroscopy, but when these blocks are used, the patient should be in the supine position for comfort.

Placement of the patient in the lateral decubitus position allows excellent access to the elbow joint (

Fig. 35-1

). The arm is placed in a padded arm holder that is attached to the side of the table. A low-profile elbow arm holder specifically designed for this purpose usually functions best.

|

|

|

|

Figure 35-1 |

A nonsterile tourniquet is then placed on the arm at the level of the arm holder, and the arm is firmly secured to the arm holder. This facilitates the arthroscopy by keeping the arm stable, just as a knee holder maintains stability during knee arthroscopy. The elbow should be positioned slightly higher than the shoulder. This allows 360-degree exposure of the elbow joint, eliminating the potential for impingement of the arthroscope or other instruments against the side of the body (

Fig. 35-2

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 35-2 |

Surgical Landmarks, Incisions, and Portals

All portal sites are marked before surgery, when the elbow is not distended or edematous and palpation of osseous landmarks is more precise (

Fig. 35-3

). Surface landmarks that should be marked with a pen on all patients are the lateral epicondyle, medial epicondyle, radial head, capitellum, and olecranon. The ulnar nerve is then palpated to be sure of its location and to check that it does not subluxate from the cubital tunnel. The location of the ulnar nerve is then marked.

|

|

|

|

Figure 35-3 |

An 18-gauge needle is placed through the planned anterolateral portal. The elbow is then distended with 20 to 30 mL of saline solution. When the joint is distended, the major neurovascular structures are positioned farther away from the starting portal site, and entry into the joint is easier and potentially safer. Attempting to enter a nondistended elbow joint accurately with a trocar is considerably difficult.

Initial portal entry can be performed safely from either the medial or the lateral side, depending on the preference of the operating surgeon. All portals are made with a No. 11 blade, which is drawn across the skin to ensure that only the skin, and not the underlying soft tissue, is divided. The neurovascular structure that is at greatest risk of injury from a lateral portal is the radial nerve. There are two techniques to reduce the risk of injury to that nerve. The first is to establish an anterolateral portal as soon as the joint is distended, before fluid extravasation makes it difficult to see and to feel the anatomic landmarks. The anterolateral portal should be established just anterior to the sulcus between the capitellum and the radial head. The other technique is to establish an anteromedial portal first. This portal is a safe distance away from the median and ulnar nerves. Then, under direct visualization with the arthroscope inside the joint, an anterolateral portal is established by placing a spinal needle into the joint and next placing a trocar and cannula. This can be a safe technique in experienced hands, but simply observing from inside of the joint, as is done with this technique, does not guarantee that the spinal needle and trocar are not being passed through the radial nerve.

Once the arthroscope (4-mm, 30-degree) has been placed into the joint, visualization is maintained by pressure distention of the capsule or mechanical retraction. Both methods work, but pressure distention leads to fluid extravasation during the course of a long arthroscopic procedure. The retractors can be simple lever retractors such as Howarth elevator or large Steinmann pins. They are placed into the elbow joint through an accessory portal, which is typically 2 to 3 cm proximal to the arthroscopic viewing portal. With the capsule and overlying soft tissue held away from the bone with the retractors, adequate visualization can be achieved with a high-flow, low-pressure system.

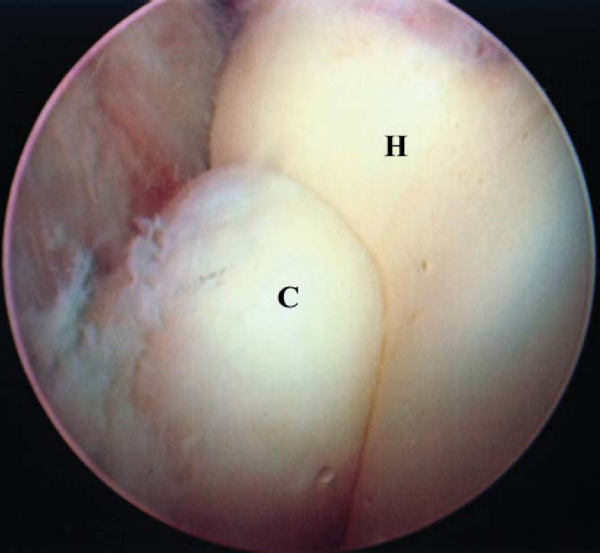

Direct Lateral or Midlateral Portal

The direct lateral or midlateral portal is located at the center of the triangle bounded by the olecranon, lateral epicondyle, and radial head. It is difficult to visualize the anterior aspect of the joint from this portal; however, it provides the best view of the posterior aspect of the capitellum, radial head, and radioulnar articulation. This is helpful, especially when one is examining a patient with osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum. Because of the shallow nature of this portal and the limited space in which to work, it can be helpful to use a 2.7-mm arthroscope.

The anteromedial portal is placed 2 cm distal and 2 cm anterior to the medial epicondyle (

Fig. 35-4

). Instruments placed through this portal tend to penetrate the common flexor origin and the brachialis before entering the joint. Before any medial portals are placed, the ulnar nerve should be palpated and checked for any tendency to subluxate from the cubital tunnel. The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve is most at risk with this portal. The median nerve is farther away, an average of 7 mm from the portal.

|

|

|

|

Figure 35-4 |

Two portals are necessary to visualize the posterior aspect of the elbow joint. The fat pad normally occupies a large portion of the potential space. A second portal is usually established simultaneously with the first since débridement with an arthroscopic shaver will be needed immediately to obtain a visible working space. The location of the ulnar nerve is confirmed before the first portal is established. Unlike the anterior portals, where palpation of the median or radial nerve is not possible, posterior portals can be established safely, once the ulnar nerve is identified.

The posterolateral portal is excellent for initial viewing of the posterior aspect of the elbow. It is made level with the tip of the olecranon, with the elbow flexed 90 degrees, at the lateral joint line. The trocar should be aimed at the center of the olecranon fossa. The direct posterior portal is established to 3 cm proximal to the tip of the olecranon, at the proximal margin of the olecranon fossa. The triceps is thick at this point, and a knife blade will be needed to penetrate directly into the elbow joint. After this portal is made, a shaver or radiofrequency probe can be placed into the joint and débridement can be performed. Loose bodies and osteophytes on the entire olecranon fossa can be removed through this portal while the surgeon views through the posterolateral portal. The arthroscope and the shaver can be switched back and forth to complete the débridement. Because of the frequent switching between portals and the relative safety of the portal location, it is not necessary to use a cannula in the posterior aspect of the elbow joint. However, an outflow cannula should be maintained in the anterior aspect of the elbow joint to limit fluid extravasation.

A good location for an initial posterior retractor portal is 2 cm proximal to the directly posterior portal. A Howarth elevator or similar type of retractor can be used to elevate the joint capsule out of view while not interfering with the working instruments. This can help with visualization of the medial and lateral gutters and also the release of a tight posterior aspect of the capsule in a stiff elbow.

Arthroscopic débridement of an osteoarthritic elbow begins in the posterior aspect of the joint when the patient predominantly lacks flexion and in the anterior aspect of the joint when the patient predominantly lacks extension (

Box 35-1

). For greater flexion to be achieved at surgery, the posterior aspect of the capsule needs to be released. This is safest and easiest to perform early in the procedure, before any swelling or fluid extravasation has occurred. In particular, release of the posteromedial aspect of the capsule requires identification of the ulnar nerve so that the nerve will not be injured (

Fig. 35-5

). If the greatest limitation of motion is in extension, the procedure should begin in the anterior compartment.

The posterior compartment is visualized well from the posterolateral portal, and the directly posterior portal can be used as a working portal. Osteophytes develop both on the tip of the olecranon and along the medial and lateral sides of the ulna. It is important to check for osteophytes on the sides of the olecranon; often, they are overlooked, and only the one on the tip of the olecranon is addressed. In addition, the olecranon fossa should be checked for osteophytes along the rim on the posterior aspect of the humerus. These osteophytes often match arthritic osseous formation on the olecranon, and both sites of bone formation need to be excised to restore normal joint motion.

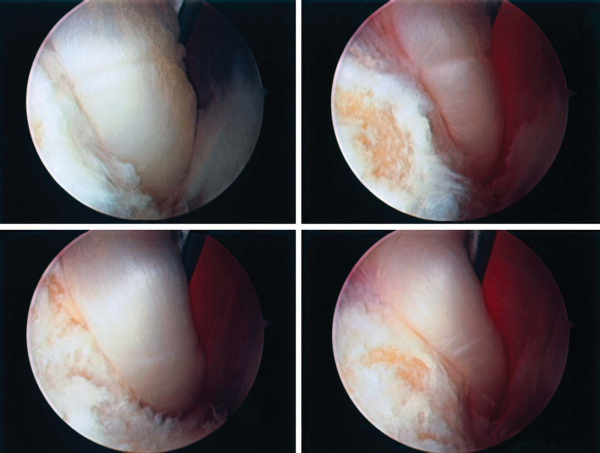

After initial joint inspection from an anterior portal and removal of obvious loose bodies, all work on bone is performed (

Fig. 35-6

). A shaver or bur can be used to remove osteophytes from the radial and coronoid fossae of the humerus. Often, these osteophytes are neglected, and only the tip of the coronoid is excised (

Fig. 35-7

). The medial aspect of the coronoid should also be examined for osteophytes, which may be missed if they are not specifically sought. Use of motorized instruments without a suction device attached allows adequate tissue removal and reduces the risk of inadvertent neurovascular injury.

|

|

|

|

Figure 35-6 |

Once all osteophytes have been excised, the anterior aspect of the capsule can be removed. It helps initially to take the capsule off of the humerus. This tends also to increase the working space in the anterior compartment. While viewing from the lateral side, the surgeon excises the anterior aspect of the capsule with a shaver or punch. The median nerve is the closest important structure, but it is behind the brachialis muscle. After the capsule is excised to the midline of the joint, the viewing portal is changed to the medial side, and the shaver is placed through the lateral portal. Care must be taken when the capsule is excised just anterior to the radial head and the capitellum. The radial nerve is at great risk for injury at this location. Often, a small fat pad can be visualized in this area. The radial nerve lies just anterior to this fat pad.

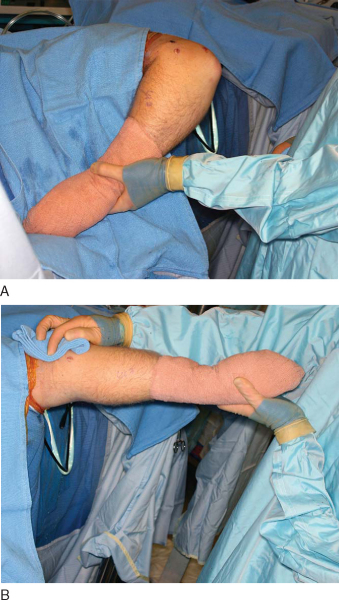

At the end of the procedure, the maximum range of motion of the elbow is evaluated and documented (

Fig. 35-8

). The elbow should then be placed in an extended position with a circumferential compressive dressing. The extended position limits the amount of swelling and accumulation of intraarticular fluid. The elbow should not be placed in flexion because this position allows the maximal amount of fluid to collect in the elbow joint. Patients are examined immediately after the surgical procedure, when they are awake in the recovery room, to confirm that the neurovascular status is stable postoperatively.

|

|

|

|

Figure 35-8 |

Elevation of the arm into a “Statue of Liberty” position overnight helps limit postoperative swelling. Motion can be delayed for 24 hours to allow edema to resolve. Continuous passive motion or splinting can then be started to help maintain the arc of motion achieved in the operating room. Continuous passive motion is often prescribed for patients who had the most restricted motion preoperatively. It is often not needed for those with a minimal loss of motion. However, there is little evidence to confirm that continuous passive motion restores motion better than splints alone or physical therapy. If continuous passive motion is used, it is typically applied for 23 hours a day, with breaks for cleaning and eating. The motion setting is started at the same maximum motion achieved in the operating room. We do not start with a gentle range of motion and “work up” to the range of motion restored in the operating room. Continuous passive motion can be used with an indwelling axillary block for paralysis and pain control for the first 24 hours, or intravenous narcotics can be used for pain control. We are not aware of any reports on the use of intraarticular catheters to deliver lidocaine or narcotics. Continuous passive motion is often used for the first 3 or 4 weeks after surgery.

Splinting is also an effective option, and it typically involves alternating periods of extension and flexion. Splinting is almost always used for patients who had the least amount of motion loss preoperatively. A static splint is thought to be the best type of splint. The patient is taught to alternate periods of flexion and extension, typically for an hour at each end of the range of motion achieved at surgery. The neurovascular status, in particular, the ulnar nerve, should be evaluated at regular intervals during postoperative rehabilitation, especially in patients in whom a significant amount of motion has been restored. An ulnar neuropathy has been noted after arthroscopic or open release in some patients who had 90 degrees or less of flexion preoperatively and in whom surgery restored substantially greater flexion. [2] [5] [15]

Complications of elbow arthroscopy include compartment syndrome, septic arthritis, and nerve injury. In a report of 473 elbow arthroscopies performed by experienced elbow arthroscopists, four types of minor complications, including infection, nerve injury, prolonged drainage, and contracture, were identified in 50 cases.[5] The most common complication was persistent portal drainage, and the most serious was deep infection. Neurologic complications were limited to transient nerve palsies; there were no permanent nerve injuries. Savoie and Field[10] reported a 3% prevalence of neurologic complications in a review of the results of 465 arthroscopy procedures presented in the literature. The rate of permanent neurologic injury appears to be higher in the elbow than in the knee or shoulder, and the risk of nerve injury at the elbow is higher in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or in those undergoing a capsular release.[5] Substantial injury involving the radial, median, and ulnar nerves has been reported during elbow arthroscopy. [4] [8] [14] The use of retractors for greater visualization and to facilitate exposure is probably the most important factor in preventing nerve injury.[5] In some cases, arthroscopic identification of nerves allows safe capsulectomy. This is particularly true with regard to the ulnar nerve.

| PEARLS AND PITFALLS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Few reports of arthroscopic débridement for treatment of osteoarthritis of the elbow are available (

Table 35-1

). The current literature has shown satisfactory results with increases in range of motion and improvement of pain. These studies suggest that arthroscopic débridement of the arthritic elbow is a reasonable option in the arthritic patient.

| Author | Results |

|---|---|

| Cohen et al[3] (2000) | 26 patients with excellent pain relief, no major complications |

| Savoie et al[11] (1999) | 24 patients; all had decrease in pain, 81-degree increase in arc of motion |

| Phillips and Strasburger[9] (1998) | Satisfactory results in 25 patients with an increase of 41 degrees in total arc of motion |

| Kim and Shin[6] (2000) | 30 patients with 92% improvement in the range of motion, from a mean of 81 degrees preoperatively to a mean of 121 degrees postoperatively |

| Adams and Steinmann[1] (2007) | 41 patients with 81% good–excellent results; postoperative range of motion, 8.4 to 131.6 degrees |

1.

Adams JE, Wolff LH III, Merten SM, Steinmann SP: Osteoarthritis of the elbow: results of arthroscopic osteophyte resection and capsulectomy. Podium Presentation, Twenty-Third Annual Open Meeting of the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons, February 17, 2007, San Diego, California.

2.

Aldridge 3rd JM, Atkins TA, Gunneson EE, Urbaniak JR: Anterior release of the elbow for extension loss.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004; 86:1955-1960.

3.

Cohen AP, Redden JF, Stanley D: Treatment of osteoarthritis of the elbow: a comparison of open and arthroscopic débridement.

Arthroscopy 2000; 16:701-706.

4.

Hahn M, Grossman JA: Ulnar nerve laceration as a result of elbow arthroscopy.

J Hand Surg Br 1998; 23:109.

5.

Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW: Complications of elbow arthroscopy.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83:25-34.

6.

Kim SJ, Shin SJ: Arthroscopic treatment for limitation of motion of the elbow.

Clin Orthop 2000; 375:140-148.

7.

O’Driscoll SW: Elbow arthritis.

J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1993; 1:106-116.

8.

Papilion JD, Neff RS, Shall LM: Compression neuropathy of the radial nerve as a complication of elbow arthroscopy: a case report and review of the literature.

Arthroscopy 1998; 4:284-286.

9.

Phillips BB, Strasburger S: Arthroscopic treatment of arthrofibrosis of the elbow joint.

Arthroscopy 1998; 14:38-44.

10.

Savoie F, Field LD: Complications of elbow arthroscopy.

In: Savoie F, Field LD, ed. Arthroscopy of the Elbow,

New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:151-156.

11.

Savoie F, Nunley PD, Field LD: Arthroscopic management of the arthritic elbow: indications, technique, and results.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999; 8:214-219.

12.

Steinmann SP: Elbow arthroscopy.

J Am Soc Surg Hand 2003; 3:199-207.

13.

Steinmann SP, King G, Savoie F: Arthroscopic treatment of the arthritic elbow.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87:2113-2121.

14.

Thomas MA, Fast A, Shapiro D: Radial nerve damage as a complication of elbow arthroscopy.

Clin Orthop 1987; 215:130-131.

15.

Wright TW, Glowczewskie Jr F, Cowin D, Wheeler DL: Ulnar nerve excursion and strain at the elbow and wrist associated with upper extremity motion.

J Hand Surg Am 2001; 26:655-662.