Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Paul D. Sponseller MD

Description

-

DDH covers a spectrum of varying degrees

of superolateral displacement of the femur and deformation of the

acetabulum, developing mostly in utero or, rarely, in infancy. -

It usually is discovered on routine screening in early childhood.

-

It occasionally is discovered in teens

with a limp or pain, in which case it probably represents a mildly

subluxed hip that could not be detected on physical examination. -

Classification by spectrum of severity (1):

-

A subluxable hip is reduced but can be subluxated with pressure and goes back to the reduced position.

-

A dislocatable hip can be fully dislocated and reduced.

-

-

A dislocated hip rests in a dislocated position and reduces only with manual effort.

-

Synonyms: DDH; Congenital dislocation of the hip (old term); Hip dysplasia; Unstable hip

General Prevention

-

No effective preventive means exist.

-

Early detection is most important (2–5).

-

Patients with hip dysplasia should have their children examined carefully at birth (5).

Epidemiology

Females are affected 4 times as often as males because of increased ligamentous laxity (1).

Incidence

-

For all degrees of instability, 1 per 200 births (1,5)

-

For full dislocation, 1 per 1,000 births (1,5)

Risk Factors

-

Breech position

-

1st-born status

-

Female gender

-

Oligohydramnios

-

Family history

-

Ehlers-Danlos or Marfan syndromes

Genetics

Increased risk occurs in persons with a positive family history, but no established Mendelian pattern.

Etiology

-

Dysplasia occurs because of unfavorable forces on the hip in utero (1).

-

Adduction of the limb, such as with oligohydramnios, directs the femoral head to the edge of the acetabulum.

-

Breech position increases hamstring tension and thus the force across the hip.

-

Ligamentous laxity, greater in females and in some families, also increases the risk.

-

The earlier in utero these factors develop, the more severe the dysplasia.

-

Postpartum factors, such as a

contralateral abduction contracture or swaddling of the limbs, prevent

some hips from stabilizing on their own.

Associated Conditions

-

Muscular torticollis

-

Foot deformities

-

Genetic syndromes (especially connective-tissue disorders and skeletal dysplasia)

Signs and Symptoms

-

No symptoms appear during the 1st few years of life (4).

-

Only careful physical examination for a

gentle clunk of the hip out of (Barlow sign) or into (Ortolani sign)

the acetabulum shows the problem. -

The affected hip may rest in slight adduction and may have a deeper proximal thigh crease, but these signs are not constant.

-

The abduction of the affected limb usually is <50° because of the changed center of rotation.

-

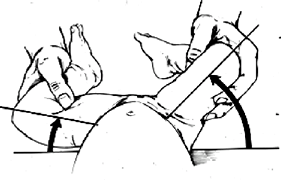

The parent may note this adduction limitation while changing the infant’s diapers (Fig. 1).

-

A click may be felt in the hip, but it is

a nonspecific sign because a click often is felt in normal hips and

comes from the meniscus of the knee, fascia lata, or a synovial fold. -

The clunk of instability usually is lost after ~6 months, when the dislocation becomes more fixed.

-

-

The child with a dysplastic hip may begin to walk on time or just a few months late.

-

After walking age, the thigh crease may become more pronounced, and the circumference may be decreased.

Fig. 1. Asymmetrical abduction of the hip is the most sensitive sign of DDH across all age groups.

Fig. 1. Asymmetrical abduction of the hip is the most sensitive sign of DDH across all age groups. -

A Trendelenburg limp may be noted (the pelvis drops when the patient stands on the dysplastic side).

-

If both sides are affected, increased lumbar lordosis may be present (4).

-

Pain develops only after cartilage degeneration starts at 18 years of age at the earliest, and often much later.

-

Associated conditions should raise the suspicion of hip dysplasia.

-

Physical Exam

-

Hip abduction is assessed.

-

Document Ortolani and Barlow tests on all newborns and repeat during well-baby checks.

-

Baby warm, quiet, and relaxed on parent’s lap

-

1 hip at a time

-

Gentle downward pressure on knee or thigh with adduction

-

Feel whether hip goes partially or fully out (Barlow test).

-

Abduct to feel it slide back in (Ortolani test).

-

Check for hip abduction (<60° is suspicious).

-

-

-

With the patient’s pelvis flat, note any

difference in the height of the 2 knees with the thighs together

(Galeazzi or Allis sign). -

Check gait in the older child.

Tests

Imaging

-

If abnormal examination or risk factors

exist, an ultrasound study is indicated in the first 6 months, before

cartilage ossifies; this procedure requires an ultrasonographer

experienced in hips (3,6). -

Arthrography shows the depth of reduction

with a 90% good outcome if <5 mm of space exists between the femoral

head and acetabulum. -

Plain radiographs are most useful after 5 months.

-

Both the shape of the acetabulum and its relation to the femur should be assessed.

-

The Shenton line should form a smooth arc from the neck of the femur to the superior ramus of the pubis.

-

The femoral epiphysis should be medial to the outer edge of the acetabulum.

-

-

MRI and CT have only limited roles in usual cases of DDH (Fig. 2).

![]() Fig.

Fig.

2. DDH was not diagnosed until age 5 in this patient. Note the

extensive proximal migration and dysplasia of both femur and acetabulum.

P.99

Pathological Findings

-

The acetabulum is flattened posterosuperiorly.

-

The femoral head is flattened anteriorly, and femoral anteversion is increased.

-

Cartilage erosion and arthritis develop after the 2nd decade.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Benign soft-tissue click from hip or knee fascia

-

Neuromuscular hip dysplasia from muscle imbalance in cerebral palsy or spina bifida

-

Congenital short femur and coxa vara, but with located hip

General Measures

-

The hip should be reduced within the 1st 6 weeks if the dislocation is recognized.

-

The earlier the diagnosis is made, the easier and safer the treatment will be.

-

Even up until age 6–8 years, reduction is worthwhile but requires surgery.

-

Treatment varies according to age.

-

Newborn:

-

Click and subluxation are followed with serial examinations.

-

Many patients improve within 1 week.

-

-

Newborn–6 months:

-

Full dislocation or persistent

instability is treated with an abduction brace, such as the Pavlik

harness, which flexes the hip beyond 90° (Fig. 3). -

Bracing should be done by an orthopaedist familiar with pediatrics.

-

The hip should reduce within 3 weeks, which should be confirmed with ultrasound or radiography.

-

A full-time brace is used until the hip

is clinically stable; then, a part-time brace is used until the hip is

radiographically normal. -

After 6 months: Closed versus open reduction

Fig. 3. Treatment of DDH with a Pavlik harness.

Fig. 3. Treatment of DDH with a Pavlik harness.

-

-

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

Minimal need exists for physical therapy because, with time, children regain strength and motion on their own.

Surgery

-

A medial or lateral approach to the hip joint is used to release the structures inside the joint that are blocking reduction.

-

Osteotomy of the pelvis or femur is done to realign the joint surface.

-

The approach depends on patient age.

-

6–24 months:

-

Many surgeons proceed with a period of skin traction first to stretch the soft tissues.

-

Closed or open reduction with the patient under anesthesia

-

After reduction, spica cast for 3–6 months

-

-

>24 months:

-

Open reduction, usually including a femoral osteotomy or iliac osteotomy

-

The results of surgical reduction decline with the increasing age of the child (7).

-

-

Prognosis

-

Untreated complete dislocation results in a permanent waddling (Trendelenburg) gait and pain by age 30–50 years at the latest (1,7).

-

Patients with subluxed, but not dislocated, hips may have pain earlier.

-

Hips that are successfully treated early may have normal function.

Complications

-

Redislocation (5%) (1–3)

-

Residual dysplasia (25%) (1–3)

-

AVN (10%) (1–3):

-

If the blood supply to the upper femur is disturbed by the process of reduction

-

It may be impossible to reverse this process fully.

-

Patient Monitoring

-

After treatment of a dysplastic hip, follow-up care is needed until the patient reaches maturity.

-

Even after successful hip reduction, a

10–25% chance exists of incomplete remodeling of the femur and

acetabulum that may require osteotomy (1–3,7)

References

1. Weinstein SL, Mubarak SJ, Wenger DR. Developmental hip dysplasia and dislocation: Part I. Instr Course Lect 2004;53:523–530.

2. Cady RB. DDH: definition, recognition, and prevention of late sequelae. Pediatr Ann 2006;35:92–101.

3. Harcke HT. Imaging methods used for children with hip dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005;434:71–77.

4. Ilfeld FW, Westin GW, Makin M. Missed or developmental dislocation of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986;203:276–281.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: recommendation statement. Pediatrics 2006;117:898–902.

6. Harcke HT, Kumar SJ. The role of ultrasound in the diagnosis and management of congenital dislocation and dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg 1991;73A:622–628.

7. Kim YH, Kim JS. Total hip arthroplasty in adult patients who had developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Arthroplasty 2005;20:1029–1036.

Codes

ICD9-CM

-

754.31 Congenital dislocation of the hip (unilateral)

-

754.32 Congenital dislocation of the hip (bilateral)

-

754.33 Congenital subluxation of the hip (unilateral)

-

754.34 Congenital subluxation of the hip (bilateral)

Patient Teaching

-

The monitoring of skin around casts and braces is important.

-

Infants in Pavlik harness should wear the device continuously until the hip is stable.

-

Older children are treated in a spica (body) cast, so walking is not possible.

-

Special car seats and wheelchairs are available.

FAQ

Q: Are all cases of developmental dysplasia detectable by physical examination?

A:

No. Physical screening tests are useful for detecting many cases in

infancy, but physical tests are neither completely sensitive nor

specific. On the other hand, the rarity of hip dysplasia means that

routine ultrasound or radiography are not indicated for all children.

No. Physical screening tests are useful for detecting many cases in

infancy, but physical tests are neither completely sensitive nor

specific. On the other hand, the rarity of hip dysplasia means that

routine ultrasound or radiography are not indicated for all children.

Q: Is double-diapering effective in treating DDH?

A:

Most experts believe that double diapering is not enough because the

diapers do not control the position of the hips accurately enough. It

may be a useful temporizing maneuver while awaiting the results of a

repeat ultrasound or obtaining a brace.

Most experts believe that double diapering is not enough because the

diapers do not control the position of the hips accurately enough. It

may be a useful temporizing maneuver while awaiting the results of a

repeat ultrasound or obtaining a brace.