Brachial Plexus Birth Palsy

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Brachial Plexus Birth Palsy

Brachial Plexus Birth Palsy

Paul D. Sponseller MD

Description

-

Brachial plexus palsy results from stretch during birth that is caused by downward or upward traction on the arm.

-

Secondarily, the muscles and bones of the

upper extremity become contracted or deformed over time because of the

resultant muscle imbalance. -

Although the injury occurs at birth, in mild cases it may not be detected until the baby tries to use the extremity (1–3).

-

Classification (3):

-

Type I (Erb palsy): Injury to roots 4–6 of the cervical spine

-

Type II (whole-brachial plexus palsy): C4–T1 involved; also known as “Erb-Duchenne-Klumpke” palsy

-

Type III (Klumpke palsy): C8–T1 involved

-

-

Synonyms: Birth palsy; Obstetric palsy; Erb palsy; Klumpke palsy

General Prevention

-

Sometimes obstetricians will advise a

caesarean section if a baby seems extremely large or cephalopelvic

disproportion is present. -

Not all cases can be anticipated or prevented.

Epidemiology

Incidence

-

Currently, the incidence is 0.8 per 1,000 live births (2).

-

This figure is a decline from the rate in 1900, when it was reported twice as often.

-

The change most likely results from improved obstetric care.

-

-

Erb palsy is ~4 times as common as Klumpke palsy.

-

No recognized difference exists in incidence between boys and girls.

Risk Factors

-

Fetal malposition

-

Shoulder dystocia

-

Cephalopelvic disproportion

-

High birth weight:

-

Maternal diabetes

-

-

Use of forceps in delivery

Pathophysiology

-

Pathologic findings vary from stretch to disruption of the nerves of the brachial plexus (3).

-

The injury may occur at the cervical

foramen as the nerves exit the spinal canal (poorer prognosis), or

farther down in the neck and shoulder. -

Secondary muscle atrophy and contracture ensues.

Etiology

-

Erb palsy results from downward traction on the shoulder or arm or lateral traction against the neck.

-

Klumpke palsy is secondary to upward traction on the arm.

-

Both occur because of the force needed in a difficult extraction.

Associated Conditions

-

High birth weight

-

Gestational diabetes

Signs and Symptoms

-

Decreased active use of the extremity

-

Arm held in internal rotation (2)

-

Loss of full active or passive external rotation

-

Inability to abduct (raise) the shoulder

-

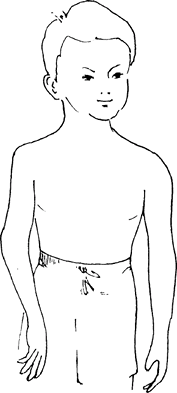

Atrophy of the involved muscles (late) (Fig. 1)

-

Elbow flexion contracture

-

Possible Horner syndrome in Klumpke palsy

-

The condition is not painful.

-

A loss of sensation may be noted with complete plexus injuries.

History

-

Decreased infant arm movements sometimes are noted from birth.

-

In other cases, more subtle decreases in shoulder movement or presence of arm contracture may not be noted until later.

Physical Exam

-

Physical examination is the primary means of diagnosis.

-

Palpate for tenderness over the clavicle, proximal humerus, and ribs.

-

Test sensation by responses to light touch or pinch.

-

Test the function of all muscles in the shoulder, elbow, and hand by stimulation and observation.

-

-

In patients with Erb palsy, the shoulder is internally rotated and lacks external rotation and abduction.

-

In Klumpke palsy, loss of finger and interosseous function occurs.

Tests

Imaging

-

Plain radiographs often are indicated at

birth to rule out other injuries that may cause decreased movement of

the infant’s arm (clavicle fracture, proximal humerus fracture); such

injuries may coexist with brachial plexus birth palsy. -

At the time of late reconstruction in a

child >4 years old who has residual shoulder imbalance, plain

radiographs and CT scans are indicated to assess the shape of the

glenohumeral joint.

Diagnostic Procedures/Surgery

-

An electromyogram should be obtained if no clinical return of deltoid or biceps function occurs by 3–6 months of age.

-

Lack of reinnervation may be a relative indication for surgery.

-

-

Cervical myelography may be helpful for diagnosing the level of injury.

-

Meningoceles seen at the root levels in

the cervical spinal cord indicate that roots were avulsed from the

cord, and the prognosis is poor. -

A finding of meningoceles indicates that different strategies may be needed at surgery.

-

Differential Diagnosis

-

Clavicle fracture:

-

Usually painful to palpation

-

Some shoulder motion may be elicited.

-

-

Proximal humeral physeal fracture:

-

Same findings as clavicle fracture, with

tenderness over the proximal humerus; the abnormality may not show on

radiographs because the proximal humerus is not ossified at birth. -

Ultrasound or MRI studies may be diagnostic, as are plain films 7–10 days later.

-

-

Septic arthritis of the shoulder:

-

May cause pseudoparalysis

-

Fever in the newborn may not be pronounced.

Fig.

Fig.

1. The most typical deformity after infantile brachial plexus palsy is

an internally rotated arm that does not abduct fully or flex at the

elbow. This deformity results from damage to the C5–C6 roots.

-

P.43

General Measures

-

Parents should stretch the infant’s arm several times a day as directed by the occupational therapist (1–3).

-

The patient should be referred to a specialized pediatric orthopaedic surgeon for monitoring and decision-making.

-

Observation and passive ROM are indicated for the newborn; ~80% of patients recover spontaneously by 1 year of age (4).

-

Splinting is not necessary, but continued follow-up is needed.

-

Surgery is indicated for the remaining

20% of patients, with grafting of the injured nerves (if no

meningoceles are present and the elapsed time is not >1–2 years) or

with tendon transfers to improve muscle balance (2–5).

Activity

-

No restrictions

-

Encourage passive ROM.

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

-

An occupational therapist is helpful in teaching the parents how to stretch and what contractures to watch for.

-

Splinting is not needed, but stretching and passive ROM are encouraged.

Surgery

-

Nerve repair/reconstruction:

-

May be performed with an operative

microscope with direct repair or grafting of the injured nerves if the

patient’s function does not return in ~6 months. -

The exact timing is controversial.

-

-

Tendon transfers may be performed later to restore external rotation to the shoulder.

-

Release of the tight internal rotators also may be indicated.

-

Humeral osteotomy is another way to restore an externally rotated position.

-

Several muscle transfers are available to restore elbow flexion, most notably the latissimus transfer.

-

Transfers for finger and wrist function are least commonly needed.

Disposition

Issues for Referral

It is important to refer the baby with brachial birth

palsy to an orthopaedic surgeon with an interest in this condition

because it is a specialized field.

palsy to an orthopaedic surgeon with an interest in this condition

because it is a specialized field.

Prognosis

-

80% of patients with brachial plexus birth palsy recover spontaneously.

-

Surgery may help many of the remainder.

Complications

-

Contracture of shoulder, elbow, or wrist

-

Affected extremity smaller in length and girth

-

Sensory loss

-

Shoulder dislocation

Patient Monitoring

The patient should be seen approximately every 2–3

months to look for return of function and to plan for appropriate

diagnostic testing.

months to look for return of function and to plan for appropriate

diagnostic testing.

References

1. Boome

RS, Kaye JC. Obstetric traction injuries of the brachial plexus.

Natural history, indications for surgical repair and results. J Bone Joint Surg 1988;70B:571–576.

RS, Kaye JC. Obstetric traction injuries of the brachial plexus.

Natural history, indications for surgical repair and results. J Bone Joint Surg 1988;70B:571–576.

2. Waters

PM, Bae DS. Effect of tendon transfers and extra-articular soft-tissue

balancing on glenohumeral development in brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg 2005;87A:320–325.

PM, Bae DS. Effect of tendon transfers and extra-articular soft-tissue

balancing on glenohumeral development in brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg 2005;87A:320–325.

3. Waters PM. Update on management of pediatric brachial plexus palsy. J Pediatr Orthop 2005;25:116–126.

4. Smith NC, Rowan P, Benson LJ, et al. Neonatal brachial plexus palsy. Outcome of absent biceps function at three months of age. J Bone Joint Surg 2004;86A:2163–2170.

5. Hoffer MM, Wickenden R, Roper B. Brachial plexus birth palsies. Results of tendon transfers to the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg 1978;60:691–695.

Codes

ICD9-CM

767.6 Brachial plexus birth palsy

Patient Teaching

-

The prognosis should be outlined to the parents, so they can plan ahead.

-

The possibility of contractures should be explained, so the parents will be motivated to continue the stretching exercises.

Activity

No activity restrictions

Prevention

-

Management of gestational diabetes

-

Caesarean delivery if cephalopelvic disproportion is clinically significant.

FAQ

Q: Why is immediate surgical repair of the brachial plexus not indicated at birth?

A:

Because most lesions are stretch lesions (neurapraxias) that will

improve spontaneously. Surgery on these nerves may disrupt intact

channels.

Because most lesions are stretch lesions (neurapraxias) that will

improve spontaneously. Surgery on these nerves may disrupt intact

channels.

Q: What is the latest age at which nerve repair may be performed?

A: It should not be performed much after the age of 12–18 months because reinnervation may not succeed.