Fractures of the Pelvis

Approximately two thirds of pelvic fractures are complicated by other

fractures and injuries to soft tissues. The fatality rate from pelvic

hemorrhage with current management techniques ranges from 5% to 20% (4,5).

Pelvic fractures generally are the result of direct trauma or of

transmission of forces through the lower extremity. The importance of

these fractures lies more in the associated soft-tissue injury and

hemorrhage than in the fracture per se (1,5,6).

-

Types

-

Type A: stable

-

Type B: rotationally unstable, but vertically and posteriorly stable

-

Type C: rotationally and vertically unstable

-

-

Subtypes, which have important influences on treatment, are presented in Table 21-1 and illustrated in Figs. 21-1, 21-2, and 21-3.

-

Fractures of the acetabulum are discussed in Chap. 22.

-

Note for historical purposes that a Malgaigne fracture is a vertical fracture or dislocation of the posterior sacroiliac joint complex involving one side of the pelvis.

-

Pelvic fractures are suspected because of pain, crepitus, or tenderness over the symphysis pubis, anterior iliac spines, iliac crest, or sacrum,

but a good roentgenographic examination is essential for diagnosis.

Patients with these injuries are often unconscious or intubated, so the

examination for stability is helpful. The iliac wings are grasped and

force-directed to the midline; instability can be detected with this

maneuver. Gentle handling of the patient minimizes further bleeding and

shock. -

Specific studies.

Patients with all but minimal trauma should have an indwelling urinary

catheter for the dual purposes of measuring urine output while the

associated shock is being treated and investigating possible bladder

trauma. If there is blood at the penile meatus, then a retrograde

urethrogram should be performed before passage of the catheter (1,2,6).

This prevents completion of a partial urethral tear. Intravenous

pyelography (IVP) and cystography document renal function, bladder

anatomy, and help delineate the size of any pelvic or retroperitoneal

hematoma. When the initial urinalysis reveals less than 20 red blood

cells per high powered field rbc/hpf, an IVP is generally not necessary

(8). Despite the difficulties involved, a

pelvic (in women) and rectal examination should be done to check for

fresh blood and open wounds, perineal sensation in a conscious patient,

a displaced unstable prostate, and sphincter tone. These fractures

frequently are associated with neurologic damage, so a careful

neurologic evaluation should be done in all patients.

-

Symptoms and signs.

At presentation, approximately 20% of patients are in shock. Severe

backache can help differentiate the pain of retroperitoneal bleeding

from the pain of intraabdominal bleeding. -

Treatment.

Pneumatic antishock garments (MAST trousers) help reduce the pelvic

volume by compression of the iliac wings. MAST trousers are not useful

as

P.300

a routine transfer aid for patients with blunt trauma (9).

These garments are useful in transport of patients where there is a

high degree of suspicion of a pelvic fracture, but should be removed as

soon as resuscitation is underway because they are associated with

compartment syndrome in the legs (10). Most

causes of hemorrhage are adequately handled by rapid replacement and

maintenance of blood volume, followed by reduction (when appropriate)

and stabilization of the fractures as described in VI.

Adequate blood replacement is the first priority, and its effectiveness

is monitored by the patient’s pulse, blood pressure, central venous

pressure, urine output, and so on, as described in Chap. 1.

Blood loss of 2500 mL is common, and blood replacement is usually

necessary even without evidence of an open hemorrhage. Diagnostic

peritoneal lavage is a useful test to rule out intraabdominal injury at

the site of hemorrhage (6). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan and abdominal ultrasound are effective (first) screening tests for this condition (2,5).

The surgeon must follow the patient’s platelet count and coagulation

studies after 4 units of blood have been given because disseminated

intravascular coagulation can result from dilution of these components.

The use of angiography and embolization of distal arterial bleeding

points with blood clot, Gelfoam, or coils has been proven to be useful (1,2).

Because only 10% of patients have identifiable arterial bleeding, the

authors prefer to stabilize the pelvis first with internal or external

fixation (1,2,5,11,1213). Anterior external fixation with one or two pins in each iliac wing is an effective means of stabilizing the pelvis

P.301P.302

when the traumatic pattern allows its use (11,14,15).

Alternatively, wrapping the patient in a hospital sheet at the level of

the iliac rings or in a commercially available pelvic binder have been

proven to be effective simple methods of decreasing the pelvic volume (4).

If the pelvic injury involves the posterior wing with a sacral fracture

or unstable sacroiliac joint injury, the antishock clamp can be

lifesaving. It requires skill, familiarity with the device, and

fluoroscopic control (16). Spica casting can also be used if the necessary expertise or equipment is not available (17).

Distal femoral pins must be incorporated into the cast. If this does

not control the bleeding, then arteriography and embolization are

indicated (2).TABLE 21-1 Substances of Pelvic FracturesType A: Stable

A1 Fractures not involving ring; avulsion injuries

A1.1 Anterior superior spine

A1.2 Anterior inferior spine

A1.3 Ischial tuberosity

A2 Stable, minimal displacement

A2.1 Iliac wing fractures

A2.2 Isolated anterior ring injuries (four-pillar)

A2.3 Stable, undisplaced, or minimally displaced fractures of the pelvic ring

A3 Transverse fractures of sacrum and coccyx

A3.1 Undisplaced transverse sacral fractures

A3.2 Displaced transverse sacral fractures

A3.3 Coccygeal fractureType B: Rotationally unstable; vertically and posteriorly stable

B1 External rotation instability; open-book injury

B1.1 Unilateral injury

B1.2 Less than 2.5-cm displacement

B2 Internal rotation instability; lateral compression injury

B2.1 Ipsilateral anterior and posterior injury

B2.2 Contralateral anterior and posterior injury; bucket-handle fracture

B3 Bilateral rotationally unstable injuryType C: Rotationally, posteriorly, and vertically unstable

C1 Unilateral injury

C1.1 Fracture through ilium

C1.2 Sacroiliac dislocation or fracture-dislocation

C1.3 Sacral fracture

C2 Bilateral injury, with one side rotationally unstable and one side vertically unstable

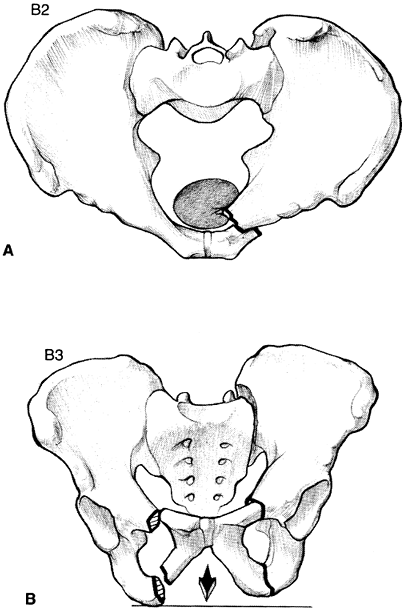

C3 Bilateral injury, with both sides completely unstableFrom Tile M. Pelvic ring fractures: should they be fixed? J Bone Joint Surg 1988;70B:I.  Figure 21-1. A: Type B1, stage 1 symphysis pubis disruption. B: Type B1, stage 2 symphysis pubis disruption. C: Type B1, stage 3 symphysis pubis disruption. (From Hansen ST, Swiontkowski MF. Orthopaedic trauma protocols. New York: Raven, 1993:228.)

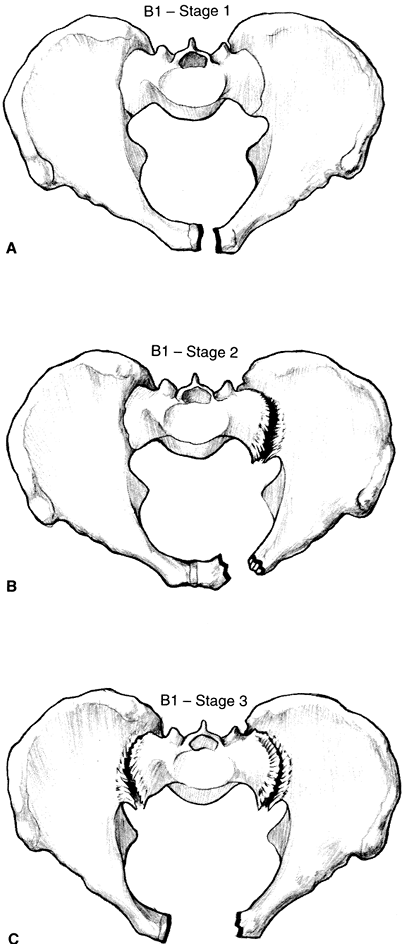

Figure 21-1. A: Type B1, stage 1 symphysis pubis disruption. B: Type B1, stage 2 symphysis pubis disruption. C: Type B1, stage 3 symphysis pubis disruption. (From Hansen ST, Swiontkowski MF. Orthopaedic trauma protocols. New York: Raven, 1993:228.)![]() Figure 21-2. A: Type B2 lateral compression injury (ipsilateral). B: Type B3 lateral compression injury (contralateral). (From Hansen ST, Swiontkowski MF. Orthopaedic trauma protocols. New York: Raven, 1993:228.)

Figure 21-2. A: Type B2 lateral compression injury (ipsilateral). B: Type B3 lateral compression injury (contralateral). (From Hansen ST, Swiontkowski MF. Orthopaedic trauma protocols. New York: Raven, 1993:228.)

-

An anteroposterior view of the pelvis

is made routinely in all patients who have suffered severe trauma or

who complain of pain in and around the pelvic region. After the

patient’s general condition has stabilized following a pelvic fracture,

special films are indicated, including a 60-degree caudad-directed

inlet view and a 40-degree cephalad-oriented tangential (or outlet)

view (7,12). The former helps visualize the posterior pelvic ring, and the latter is for the anterior ring. -

CT scans can be most useful in defining posterior ring fractures (1,2,13). Fifty percent of sacral fractures are missed on plain roentgenograms, but they are well visualized on CT scans.

-

Stable A type fractures

are treated symptomatically. Turn the patient by logrolling or begin

treatment on a Foster frame until the severe pain subsides. As soon as

the patient can move comfortably in bed, he or she can ambulate in a

walker and progress to walking with crutches. The fractures are through

cancellous bone that has good blood supply, and stability of the

P.303P.304

fracture

usually is present in 3 to 6 weeks, with excellent healing expected

within 2 months. Because of the dense plexus of nerves about the sacrum

and coccyx, injuries to this area may produce chronic pain, especially

if the patient is not encouraged to accept some discomfort and start an

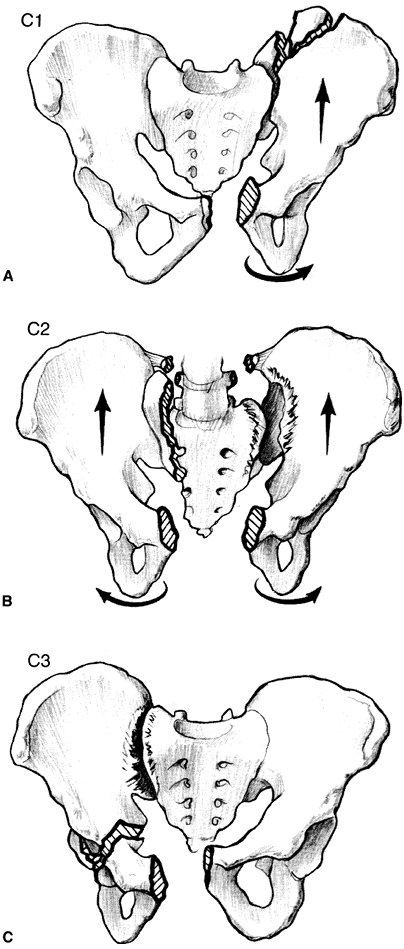

early active exercise program. Figure 21-3. A: Type C1 pelvic injury. B: Type C2 pelvic injury. C: Type C3 pelvic injury. (From Hansen ST, Swiontkowski MF. Orthopaedic trauma protocols. New York: Raven, 1993:229.)

Figure 21-3. A: Type C1 pelvic injury. B: Type C2 pelvic injury. C: Type C3 pelvic injury. (From Hansen ST, Swiontkowski MF. Orthopaedic trauma protocols. New York: Raven, 1993:229.) -

Type B fractures

(rotationally unstable, but vertically and posteriorly stable) must be

treated on an individual basis. Fracture displacements, associated

injuries, age of the patient, and functional demands should be taken

into account (1,5,13).

In open-book fractures, disruption of the anterior sacroiliac joints

and sacrospinous ligaments occurs if the displacement is more than 2.5

cm. These may be reduced and stabilized by external fixation or plate

fixation across the symphysis (11,12).

The authors generally prefer plate fixation because of the problems

with patient comfort, pin tract infection, and loosening and loss of

reduction with external fixation (5,14,18).

Minimally displaced B1, B2, and B3 injuries may be treated

conservatively with bed to wheelchair mobilization for 6 to 8 weeks,

followed by crutch ambulation with weight bearing to tolerance on the

side of the pelvis where the posterior ring is uninjured or more

stable. Internal fixation is used for more widely displaced and

unstable injuries (2,12,13). Traction is not recommended because of patient morbidity and the inability to improve fracture displacements. -

Type C minimally displaced isolated injuries, especially those involving the ilium, may be treated conservatively as in B.

However, patients need to be followed up closely roentgenographically

and, if fracture displacement is increasing, reduction and fixation is

indicated. Some centers utilize simulated weight-bearing radiographs as

a method for detecting fracture instability. Improved results with

internal fixation over traction treatment have been documented (12).

If seen early on, then fractures of the sacrum and sacroiliac joints

can be managed with closed reduction and percutaneous lag screw

fixation (2,13).

Because of the complexity of reduction and fixation techniques as well

as the potential for high morbidity resulting from adjacent

neurovascular structures, patients with type C injuries should be

referred to an experienced pelvic and acetabular surgeon.

-

Complications from associated injuries (e.g., of the bladder, cranium, chest)

-

Persistent symptoms from sacroiliac joint instability, including pain and leg length inequality

-

Chronic pain patterns from injuries around the coccyx and sacrum and sacroiliac joint (19,15), including dyspareunia

-

Persistent neurologic deficit from nerve root injury with L5, S1, and distal sacral root injuries most common; erectile dysfunction is common in males

-

Pulmonary and fat emboli

-

Infection from bacterial seeding of the large hematomas or from open pelvic fractures (20). Injuries to the large bowel are not uncommon.

hemorrhage, limited weight bearing (6–8 weeks) for lateral compression

fractures that do not have significant deformity, non–weight bearing

for other nondisplaced patterns for 8 to 12 weeks, follow-up

radiographs to check for late instability

Ongoing hemorrhage (external fixation or posterior pelvic clamp),

displaced posterior pelvic injury, symphysis widening more than 2.5 cm,

unacceptable pelvic deformity

Symphysis plating, posterior iliosacral screws. Open reduction and

iliosacral screw placement is safest; consider percutaneous iliosacral

screws in thin patient with minimal deformity. Occasionally, anterior

sacroiliac joint fixation is performed if posterior skin is not safe or

if the injury is associated with an ipsilateral acetabular fracture.

GS, Leit ME, Gruen RJ, et al. The acute management of neurodynamically

unstable multiple trauma patients with pelvic ring fractures. J Trauma 1994;36:706–713.

TA, Fleisher GR, Mahboubi S, et al. Hematuria and clinical findings as

indications for intravenous pyelography in pediatric blunt renal

trauma. Pediatrics 1988;82:216–222.

ML Jr, Kreger PI, Simonian PT, et al. Early results of percutaneous

iliosacral screws placed with the patient in the supine position. J Orthop Trauma 1995;9:207–214.

JV, Trenhaile SW, Miranda M, et al. Vertical shear injuries: is there a

relationship between residual displacement and functional outcome? J Trauma 1999;46:1024–1030.

J, Hirvensalo E, Bostman O, et al. Failure of reduction with an

external fixator in the management of injuries of the pelvic ring

long-term evaluation of 110 patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1999;81:955–962.

CE, Bosse MJ, McCarthy ML, et al. Effect of trauma and pelvis fracture

on female genitourinary, sexual and reproductive function. J Orthop Trauma 1997;11:73–81.

DJ, Olson SA, Matta JM. Diagnosis and management of closed internal

degloving injuries associated with pelvic and acetabular fractures: the

morel-lavallee lesion. J Trauma 1997;42:1048–1051.