The Deep Tendon or Muscle Stretch Reflexes

passively stretched, its fibers resist the stretch by contracting.

Reflexes elicited by application of a stretch stimulus to either

tendons or periosteum, or occasionally to bones, joints, fascia, or

aponeurotic structures are usually referred to as muscle stretch or

deep tendon reflexes. The reflex is caused by sudden muscle stretch,

brought about by percussion of its tendon. Occasionally, the tendon is

stretched by percussing a structure to which it is attached, as in the

jaw jerk. Because of their critical roles in maintaining an erect

posture, the extensor muscles of the legs, quadriceps and calf muscles,

have better developed stretch reflexes than the flexors.

superficial or cutaneous reflexes, which are quite different. The term

deep tendon reflex (DTR) was introduced in 1875, and since at least

1885 some authorities have criticized it. The term DTR is in much wider

use than muscle stretch reflex, and for both pragmatic and

anti-pedantic reasons, the DTR abbreviation will be used in this text.

tools and poor technique. These reflexes are best tested using a

high-quality rubber percussion hammer. To properly obtain a reflex, a

crisp blow must be delivered to quickly stretch the tendon. A heavy,

high-quality reflex hammer is immensely helpful for this task. Proper

technique is much more difficult to describe than to demonstrate. The

hammer strike should be quick, direct, crisp, and forceful, but no

greater than necessary. The most effective blow is delivered quickly

with a flick of the wrist, holding the handle of the hammer near its

end and letting it spin through loosely held fingertips. Putting the

index finger on top of the handle and using primarily elbow motion,

common faults, make it much harder to achieve adequate velocity at the

hammer head. Another common mistake is “pecking”: striking the tendon

with a timid, decelerating blow, pulling back at the last instant.

positioned. It may help relaxation to divert the patient’s attention

with light conversation. Sometimes, as in the ankle reflex, positioning

includes passively stretching the muscle slightly. An adequate stimulus

must be delivered to the proper spot. Reinforcement methods are

necessary if the reflex is not obtainable in the usual way. The part of

the body to be tested should be in an optimal position for the

response, usually about midway in the range of motion of the muscle to

be tested. In order to compare the reflexes on the two sides of the

body, the position of the extremities should be symmetric. During the

reflex examination, the patient should keep the head straight, since

looking to one side may alter reflex tone, especially in the arms

(tonic neck reflex). The DTRs may be influenced to some degree by

voluntary mental effort. Merely by concentrating some individuals are

able to somehow alter reflex excitability. Mentally induced reflex

asymmetry is possible and may be clinically relevant in some cases.

|

TABLE 28.1 The Commonly Elicited Deep Tendon (Muscle Stretch) Reflexes

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Placing one hand over the muscle is often useful, especially when

responses are sluggish. A reflex quadriceps contraction can sometimes

be felt even when insufficient to produce visible contraction or knee

movement. The activity of a reflex is judged by the speed and vigor of

the response, the range of movement, and the duration of the

contraction. An absent reflex often makes a dull, thudding sound when

the tendon is struck.

brachioradialis, knee (quadriceps), and ankle (Achilles) tendon

reflexes. Table 28.1 summarizes the reflex

levels. Reflexes may be graded as absent, sluggish or diminished,

normal, exaggerated, and markedly hyperactive. For the purposes of

clinical note taking, most neurologists grade the DTRs numerically, as

follows: 0 = absent; 1 + (or +) = present but diminished; 2+ (or + +) =

normal; 3+ (or + + +) = increased but not necessarily to a pathologic

degree; and 4+ (or + + + +) = markedly hyperactive, pathologic, often

with extra beats or accompanying sustained clonus. The “+” after the

number is more traditional than informative, and is sometimes omitted.

Signs are sometimes used to indicate subtle asymmetry, but generally a

grade of 2 means the same as 2+. Another level, trace (or +/-), is

frequently added to refer to a reflex, most often an ankle jerk, that

appears absent to routine testing but can be elicited with

reinforcement. Some add a grade of 5 + for the patient with extreme

spasticity and clonus. In the 0 to 4 scale, level 1 + DTRs are still

normal but somewhat sluggish and difficult to elicit, hypoactive but in

the examiner’s opinion not pathologic. Grade 3+ reflexes are “fast

normal,” quicker than 2+, sometimes very quick, but not accompanied by

any other signs of upper motor neuron pathology such as increased tone,

upgoing toes, or sustained clonus. Normality of the superficial

reflexes, normal lower-extremity tone, and downgoing toes are

reassuring evidence of fast normal rather than pathologically quick

reflexes. Some use 3+ to indicate the presence of spread or unsustained

clonus, with all other normal reflexes, even very fast ones, labeled as

2+. Grade 4+ reflexes are unequivocally pathological. The speed of the

response is very fast, the threshold low, the reflexogenic zone wide,

and there are accompanying signs of corticospinal tract dysfunction.

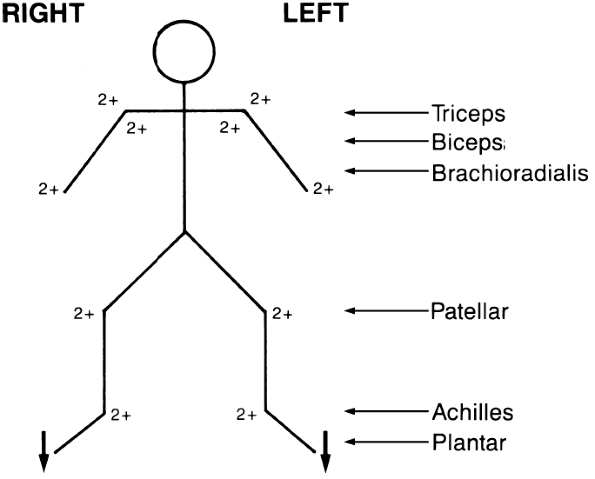

Other scales are in use, but not widely. Reflexes may be charted in

several ways, for example, as shown in Table 28.2, or as in Figure 28.1.

muscles that have not been directly stretched, even in normal patients.

The response may involve adjacent or even contralateral muscles, and

the contraction of one muscle may be accompanied by contraction of

other muscles. This is referred to as spread, or irradiation, of

reflexes. It is normal for percussion of the brachioradialis tendon to

also cause slight finger flexion. In the presence of spasticity and

hyperreflexia, contraction of the biceps or brachioradialis may be

accompanied by pronounced flexion of the fingers and adduction of the

thumb. Extension of the knee may be accompanied by adduction of the

hip, or there may be bilateral knee extension. Judging how much spread

is still within normal limits can be difficult. Under some

circumstances, the expected response to percussion of a tendon is

absent, but muscles innervated by adjacent spinal cord segments

contract instead (e.g., inverted brachioradialis reflex). On other

occasions, a reflex is absent and percussion of the tendon causes an

inverted or

paradoxical

contraction, e.g., elbow flexion on attempted elicitation of the

triceps reflex (see Inverted and Perverted Reflexes further on).

|

TABLE 28.2 Method of Recording the Commonly Tested Deep Tendon (Muscle Stretch) Reflexes

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

even apparently absent, although there is no other evidence of nervous

system disease. Under such circumstances, reinforcement techniques are

often useful. Reflex reinforcement probably involves supraspinal,

fusimotor, and longloop mechanisms. A reflex can be reinforced or

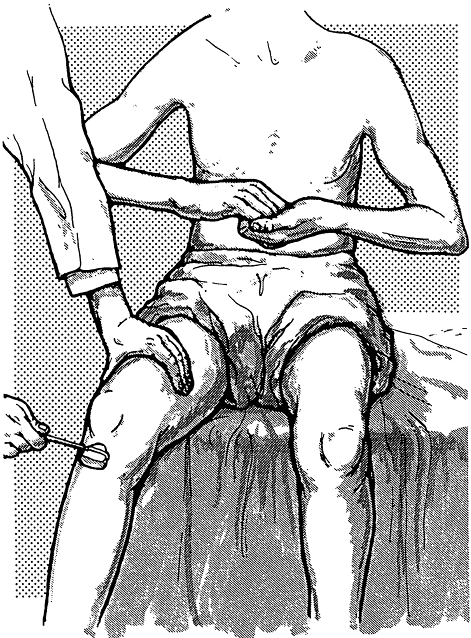

brought out using several methods. In the Jendrassik maneuver, the

patient attempts to pull the hands apart with the fingers flexed and

hooked together, palms facing, as the tendon is percussed (Figure 28.2).

The effect is very brief, lasting only 1 to 6 seconds, and is maximal

for only 300 milliseconds. The Jendrassik maneuver is obviously only

useful for lower-extremity reflexes. Other techniques include having

the patient clench one or both fists, firmly grasp the arm of the

chair, side of the bed, or the arm of the examiner. Reinforcement may

also be carried out by having the patient look at the ceiling, grit the

teeth, cough, squeeze the knees together, take a deep breath, count,

read aloud, or repeat verses at the time

the

reflex is being tested. A sudden loud noise, a painful stimulus

elsewhere on the body—such as the pulling of a hair or a bright light

flashed in the eyes—may also be a means of reinforcement.

|

|

FIGURE 28.1 • Alternate method of recording the commonly tested muscle stretch reflexes. For grading, see text and Table 28.2.

|

|

|

FIGURE 28.2 • Method of reinforcing the patellar reflex.

|

reflex reinforcement. A slight increase in tension of the muscle being

tested may reinforce the reflex response. A simple and effective method

to reinforce a knee or ankle jerk is to have the patient maintain a

slight, steady contraction of the muscle whose tendon is being tested

(e.g., slight plantar flexion by pushing the ball of the foot against

the floor or the examiner’s hand to reinforce the ankle jerk). The

patient may tense the quadriceps by extending the knee slightly against

resistance as the knee jerk is being elicited. Reinforcement may

increase the amplitude of a sluggish reflex or bring out a latent

reflex not otherwise obtainable. Reflexes that are normal on

reinforcement, even though not present without reinforcement, may be

considered normal. Slight muscle contraction due to inability to relax

may be one reason for the slightly hyperactive reflexes often seen in

patients who are tense or anxious.

Under most circumstances, weakness accompanied by hyporeflexia is of

lower motor neuron origin, and weakness accompanied by hyperreflexia of

upper motor neuron origin. The presence of pathologic reflexes and

abnormalities of associated movements are also helpful in the

differential diagnosis (Table 28.3).

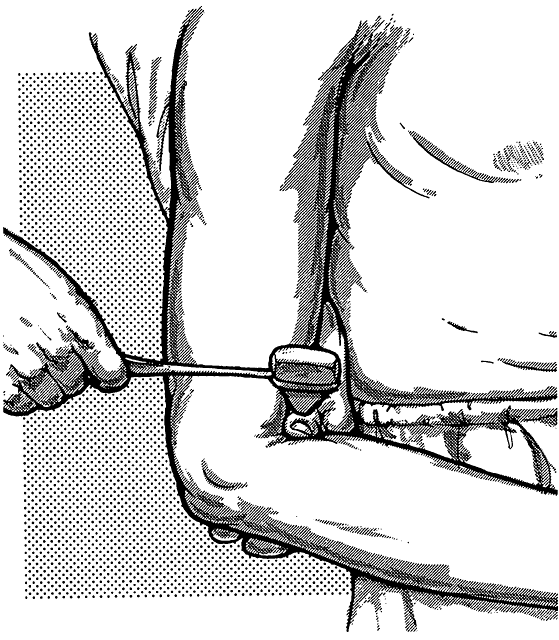

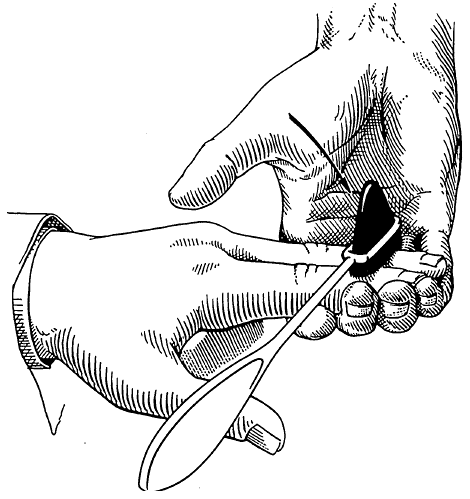

and midway between flexion and extension, the examiner places the

palmar surface of her extended thumb or finger on the patient’s biceps

tendon, and then strikes the extensor surface with the reflex hammer (Figure 28.3).

Pressure on the tendon should be light; too much pressure exerted with

the thumb or finger against the tendon makes the reflex much harder to

obtain. The hands may lie in the patient’s lap, or the examiner

may

hold the patient’s arm with the elbow resting in her hand. The major

response is a contraction of the biceps muscle with flexion of the

elbow. Since the biceps is also a supinator, there is often a certain

amount of supination. If the reflex is exaggerated, the reflexogenic

zone is increased and the reflex may even be obtained by tapping the

clavicle; there may be abnormal spread with accompanying flexion of the

wrist and fingers and adduction of the thumb.

|

TABLE 28.3 Reflex Patterns with Different Neurologic Disorders

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

FIGURE 28.3 • Method of obtaining the biceps reflex.

|

|

|

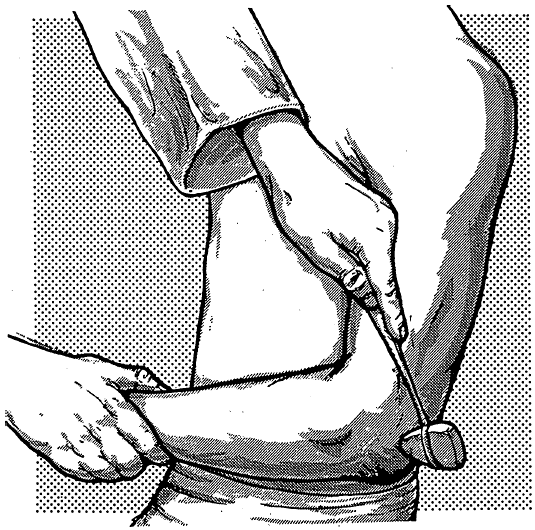

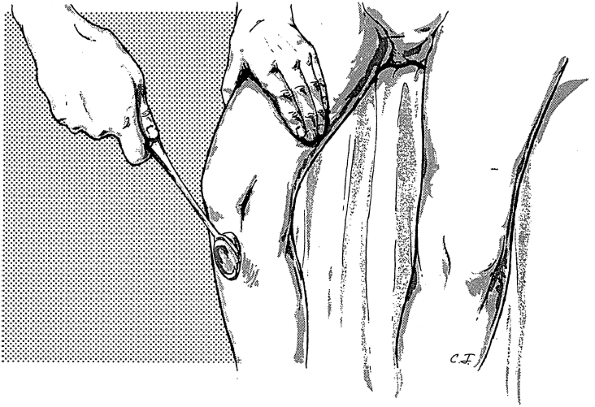

FIGURE 28.4 • Method of obtaining the triceps reflex.

|

just above its insertion on the olecranon process of the ulna. The arm

is placed midway between flexion and extension, and may be rested in

the patient’s lap, on her thigh or hip, or on the examiner’s hand (Figure 28.4).

The response is contraction of the triceps muscle with extension of the

elbow. The most common error in eliciting the triceps jerk is simply

too timorous a blow.

with the forearm in semiflexion and semipronation causes flexion of the

elbow, with variable supination (Figure 28.5). The supination is

more marked with the forearm extended and pronated, but there is less

flexion. The principal muscle involved is the brachioradialis. The

tendon can be percussed not only at its insertion on the lateral aspect

of the base of the styloid process of the radius, but also at about the

junction of the middle and distal thirds of the forearm or at its

tendon of origin above the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. The most

common error is hitting the muscle belly rather than the tendon. The

muscle becomes tendinous at about midforearm. A local contraction can

be elicited from any muscle by directly striking the muscle belly. The

point in eliciting a DTR is to lengthen the muscle by stretching its

tendon. An idiomuscular contraction can be obtained by striking the

brachioradialis muscle belly in the proximal third of the forearm; this

is not a DTR. If the reflex is exaggerated, there is associated flexion

of the wrist and fingers, with adduction of the forearm. When the

afferent limb of the reflex is impaired, there may be a twitch of the

flexors of the hand and fingers without flexion and supination of the

elbow; this is termed inversion of the reflex.

|

|

FIGURE 28.5 • Method of obtaining the brachioradialis reflex.

|

|

|

FIGURE 28.6 • Method of obtaining the finger flexor reflex.

|

is in supination, resting on a table or a solid surface, with the

fingers slightly flexed. The examiner places her fingers against the

patient’s fingers, and taps the backs of her own fingers lightly with

the reflex hammer (Figure 28.6). The response

is flexion of the patient’s fingers and the distal phalanx of the

thumb. The reflex may be reinforced by having the patient flex her

fingers slightly as the blow is delivered. An alternate technique is

for the patient to hold the hand in the air, palm down, the examiner

touching fingers with palm up, with the blow delivered in an upward

direction from below.

femoris muscle, with resulting extension of the knee, in response to

percussion of the patellar tendon. A firm tap on the tendon draws the

patella down, stretching the quadriceps, provoking reflex contraction.

If the reflex is brisk, the contraction is strong and the amplitude of

the movement is large. If the examiner places one hand over the muscle,

and with the other hand taps the patellar tendon just below the

patella, she can palpate the contraction as well as observe the

rapidity and range of response. Palpation helps in judging the latency

between the time of the stimulus and the resulting response. The knee

jerk can be elicited in various ways.

The

patient may sit in a chair with the knees slightly extended and the

heels resting on the floor, or sit on an examination table with the

legs dangling (Figure 28.7).

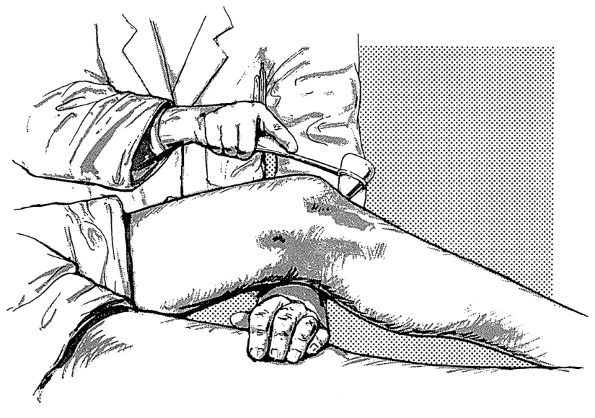

If the patient is lying in bed, the examiner should partially flex the

knee by placing one hand beneath it and then tap the tendon (Figure 28.8).

|

|

FIGURE 28.7 • Method of obtaining the patellar (quadriceps) reflex with the patient seated.

|

accompanied by adduction of the hip, which on occasion is bilateral, or

there may be bilateral knee extension. If the reflex is exaggerated,

the response may be obtained not only by tapping the tendon in the

usual spot, but also just above the patella (suprapatellar or

epipatellar reflex); the tendon can be tapped directly, or, with the

patient recumbent, the examiner can place her index finger on the upper

border of the patella and tap the finger to push down the patella.

Contraction of the quadriceps causes a brisk upward movement of the

tendon, together with extension of the leg (Figure 28.9). Marked exaggeration of the patellar reflex may be accompanied by patellar clonus.

|

|

FIGURE 28.8 • Method of obtaining the patellar (quadriceps) reflex with the patient recumbent.

|

|

|

FIGURE 28.9 • Method of obtaining the suprapatellar reflex.

|

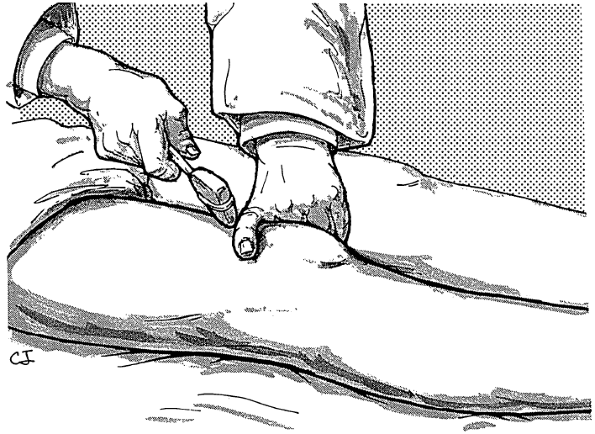

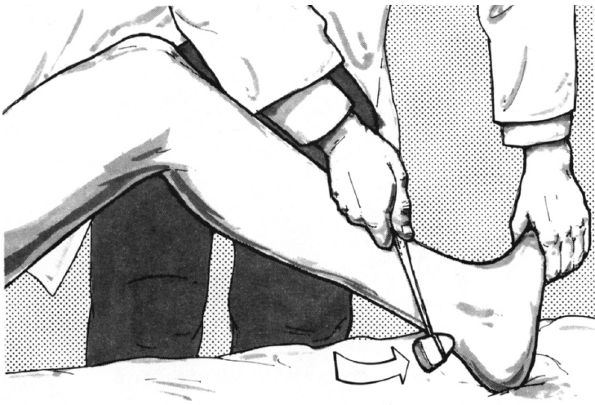

tendon just above its insertion on the calcaneus. The resulting

contraction of the posterior crural muscles, the gastrocnemius, soleus,

and plantaris, causes plantar flexion of the foot at the ankle. If the

patient is seated or lying in bed, the thigh should be held in moderate

abduction and external rotation and the knee flexed. If the patient is

supine, access to the tendon requires placing the legs into a frog-leg

position with the knees apart and the ankles close together. Some

prefer to have the patient cross the leg to be examined atop the other

shin or ankle (“figure four position,” as the legs form a 4). The

examiner should place one hand under the foot and pull upward slightly

to passively dorsiflex the ankle to about a right angle (Figure 28.10). The Achilles reflex is mediated by the tibial nerve (S1).

master. There are two critical variables: proper stretch and efficient

striking. Of the two, proper stretch is the more difficult to learn. If

the reflex is difficult to obtain, the patient may be asked to press

her foot lightly against the examiner’s hand in order to tense the

muscle and reinforce the reflex. Using a driving analogy and asking the

patient to imagine pressing on an accelerator enough to go “17 mph”

communicates the need for

a

low-level but precisely graded contraction, which is then easy to

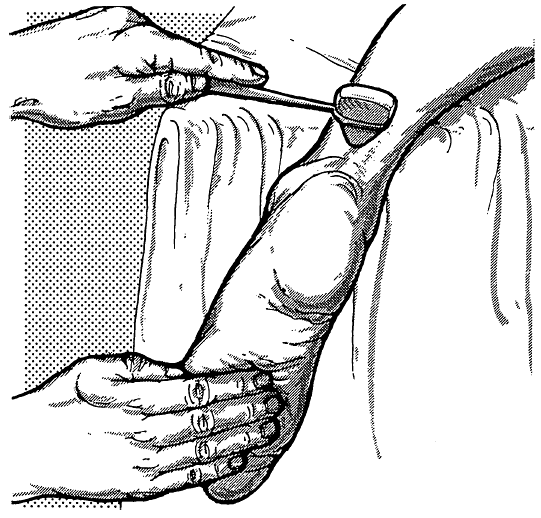

adjust up or down to the proper level. The reflex may also be elicited

by having the patient kneel on a chair or similar surface, with the

feet projecting at right angles; the Achilles tendons are percussed

while the patient is in this position (Figure 28.11).

This method is particularly useful for comparing reflex activity on the

two sides. Another method for supine examination is to strike the ball

(sole) of the foot, or strike the examiner’s hand placed flat against

the sole. This plantar stretch reflex is considered equivalent to the

ankle jerk for clinical purposes. Although the Achilles reflex, when

carefully elicited, should be present in normal individuals, it tends

to diminish with age and its bilateral absence in elderly individuals

is not necessarily of clinical significance.

|

|

FIGURE 28.10 • Method of obtaining the Achilles (triceps surae) reflex with the patient recumbent.

|

|

|

FIGURE 28.11 • Method of obtaining the Achilles (triceps surae) reflex with the patient kneeling.

|

under most circumstances, and using good technique, these are

elicitable in every normal person. One or more of these reflexes may be

absent in occasional individuals with no other evidence of disease of

the nervous system. They are present even in the majority of premature

infants. The activity of a DTR is judged by the latency, speed, vigor,

and duration of contraction, and the range of movement. Of these, the

latent period between the time the stimulus is applied and the time the

response occurs is most important for clinical evaluation of disease

states.

hypoactive, the response varies from diminished or sluggish to complete

absence of the reflex. Hyperactive reflexes are characterized by

varying degrees of decreased latency, increased speed and vigor of

response, increased range of movement, decrease in threshold, extension

of the reflexogenic zone, and prolongation of the muscular contraction.

Table 28.3 summarizes the patterns of reflex responses seen with lesions at various sites.

Clearly hyperactive or hypoactive reflexes speak for themselves. But a

reflex that is normal in absolute terms may be judged abnormal in

comparison to the patient’s other reflexes. The reflexes should be

compared on the two sides of the body, the arms to the legs, and the

knees to the ankles. The DTRs are normally symmetric, and reflexes

otherwise normal may be abnormal if different from expected. For

example, a 1 + biceps jerk in a patient with suspected cervical

radiculopathy, while “normal,” may be judged abnormal if the

opposite

biceps jerk is 2+. The DTRs are usually comparable in the upper and

lower extremities. Slight differences are permissible but a pronounced

difference may be significant (e.g., in thoracic myelopathy the DTRs in

the legs may be much brisker than in the arms, even though not clearly

pathologic). A proximal to distal gradient may also be significant.

Symmetric 1+ ankle jerks when all of the other reflexes are 2+ may

signal mild peripheral neuropathy. When asymmetry is the main finding,

it is sometimes difficult to tell whether one side is increased or the

other side decreased.

|

|

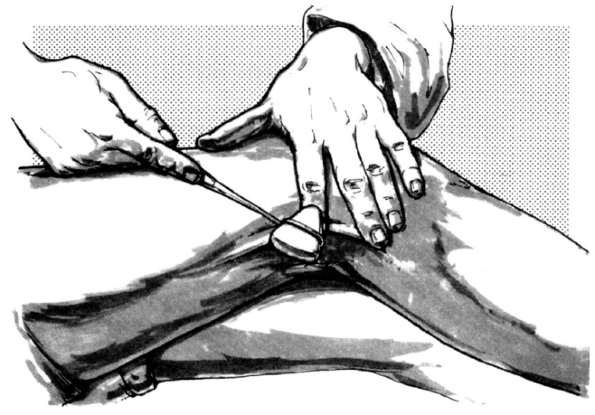

FIGURE 28.12 • Method of obtaining the biceps femoris reflex.

|

response and/or a diminution in the range of response. An increase in

stimulus intensity may be necessary to elicit the reflex, or repeated

blows may be necessary, for a single stimulus may be subliminal. A DTR

is absent if it is not obtained even with reinforcement. A depressed or

absent reflex results from dysfunction of some component of the reflex

arc. Interference with the afferent limb may be caused by lesions

involving the sensory nerve, posterior root, dorsal root ganglion, or

intramedullary pathways between the dorsal root entry zone and the

anterior horn (e.g., syringomyelia). Abnormalities of the motor unit

and final common pathway that make up the efferent limb of the reflex

arc occur in many conditions, but particularly with radiculopathy and

peripheral nerve lesions. In neurogenic processes, DTRs are lost out of

proportion to atrophy and weakness. With a peripheral nerve lesion, a

reflex may not return until much of the motor function has recovered.

Sometimes there is persistent areflexia following lesions of the nerve

root or peripheral nerve, even after complete return of both motor and

sensory functions.

a decrease in reflex threshold; a decrease in the latency, the time

between tendon percussion and the reflex contraction; an exaggeration

of the power and range of movement; prolongation of the reflex

contraction; extension of the reflexogenic zone (or zone of

provocation); and spread of the reflex response. When the reflex

threshold is decreased, a minimal stimulus may evoke the reflex, and

reflexes that are not normally obtained may be elicited with ease. Very

hyperactive DTRs may sometimes be elicited with extremely slight

percussion. Another manifestation of decreased reflex threshold may be

a widening of the area from

which

the reflex may be elicited, and application of the stimulus to sites at

some distance from the usual one may evoke the response; the patellar

reflex may be elicited by tapping the tibia or dorsum of the foot, and

the biceps and other arm reflexes by tapping the clavicle or scapula.

There may also be abnormal spread of the response. One stimulus may

provoke repetitive responses and sometimes elicit sustained clonus.

corticospinal or pyramidal system. Spasticity and hyperreflexia are

likely related to involvement of a variety of structures in the

descending motor pathways at cortical, subcortical, midbrain, and

brainstem levels. Hyperreflexia results from a lowering of the reflex

threshold due to increased excitability of the lower motor neuron pool

related to dysfunction of some or all of these structures. A lesion at

any level of the corticospinal system or other related upper motor

neuron components, from the motor cortex to just above the segment of

origin of a reflex arc, will be accompanied by spasticity and

hyperreflexia. The characteristic posture in hemiplegia is flexion of

the upper extremities, with more marked weakness of the extensors; and

extension of the lower extremities, with more marked weakness of the

flexors. Consequently, the flexor reflexes are exaggerated to a greater

degree in the upper extremities, and the extensor reflexes in the

lower. The reflexes may be present in spinal cord lesions in spite of

the absence of sensation.

The reflexes vary in these conditions; they may be normal, or they may

be decreased owing to voluntary or involuntary tension of the

antagonistic muscle, but they are most frequently increased.

Hyperactivity may be marked, but it is an exaggeration not in the speed

of the response but in the excursion or range of response. The foot may

be kicked far into the air and held extended for a time after the

patellar tendon is tapped, but the contraction and relaxation takes

place at a normal rate. There is often a bilateral response with

extraneous and superfluous jerking of remote parts, including whole

body jerks, when a reflex is tested. There is no increase in the

reflexogenic zone in psychogenic lesions, and although there may be

irregular repeated jerky movements (spurious clonus), no true clonus is

present. Furthermore, there are no other signs of organic disease of

the corticospinal system.

and pendular: Eliciting the patellar reflex while the foot is hanging

free may elicit a series of to-and-fro pendular movements of the foot

and leg before the limb finally comes to rest.

results. In the presence of hyperreflexia, there may be spread to other

muscles, as in the crossed adductor response. Inverted or paradoxical

reflexes are contractions the opposite of those expected. With an

inverted triceps or patellar reflex there is elbow or knee flexion

instead of extension. Under these circumstances, the segmental reflex

is absent, but there is an underlying hyperreflexia lowering the

threshold for activation of the antagonist muscle, perhaps because of

transmitted vibration. Degenerative spine disease with

radiculomyelopathy is the usual mechanism. An inverted brachioradialis

(often referred to as an inverted radial periosteal) reflex does not

result in true inversion (i.e., elbow extension), but instead produces

a perverted response with finger flexion. When the brachioradialis

reflex is present this finger flexion is simply referred to as spread;

when the brachioradialis reflex is absent and the only response is

finger flexion, the reflex is commonly said to be inverted.