SURGICAL APPROACHES TO THE UPPER EXTREMITY

– SURGICAL PRINCIPLES AND TECHNIQUES > CHAPTER 1 – SURGICAL

APPROACHES TO THE UPPER EXTREMITY

understanding of the surgical exposure, however, can minimize tissue

injury and expedite the procedure. Proper exposure protects the

important neurovascular structures by providing direct observation or

enabling total avoidance. The surgical exposures described in this

chapter allow excellent exposure of the upper extremities.

upper extremity are done under tourniquet control, a cut vessel

requires immediate coagulation or ligation. Otherwise, it retracts,

goes into spasm, and may later start bleeding. Never purposely cut a

cutaneous nerve. Every severed nerve forms a neuroma, and every neuroma

can become exquisitely tender. Always strive for a cosmetically

acceptable scar using, if possible, subcuticular sutures with

Steri-strips.

necessary. Infection, arthritis, or posterior dislocation of this joint

may necessitate an open procedure.

-

If resecting the medial clavicle, remove 1.5 cm of bone, staying medial to the costoclavicular ligament.

-

For a posterior dislocation, release of

the sternocleidomastoid muscle origin superiorly may improve the

exposure. Be very careful of the vital structures posterior to the SC

joint (i.e., right innominate artery, left common carotid artery,

subclavian vein, and lung tissue).

-

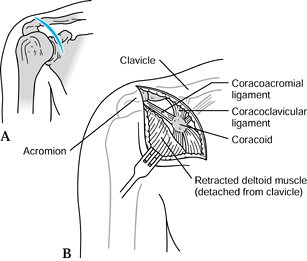

Make a 6–7 cm, anterior to posterior

saber incision just medial to the AC joint. Incise the trapezius and

deltoid fascia, and elevate off the clavicle as needed. -

Cut the capsule perpendicular to the

joint and reflect it anteriorly and posteriorly to expose the joint. It

is important to reattach this capsule to close the space created if the

distal clavicle has been resected. -

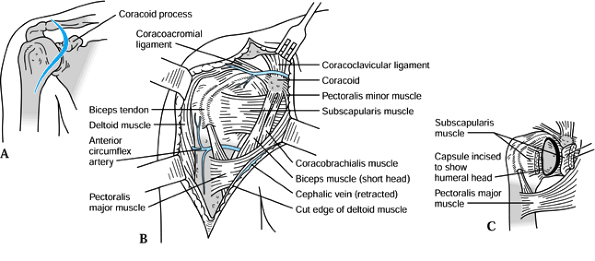

If repair or reconstruction of the

coracoclavicular ligaments is required, extend the exposure inferiorly

to expose the coracoid process. This is best done by splitting the

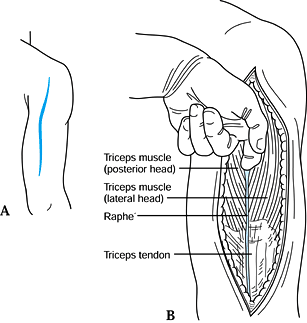

deltoid or utilizing the deltopectoral interval (Fig. 1.1). Figure 1.1. Exposure of the acromioclavicular joint and coracoid process.

Figure 1.1. Exposure of the acromioclavicular joint and coracoid process.

used to treat recurrent anterior shoulder dislocations, fractures of

the proximal humerus, rotator cuff repairs or reconstructions, and

anterior shoulder arthrotomies and arthroplasties (Fig. 1.2).

|

|

Figure 1.2. Henry’s anterior approach.

|

-

Position the patient in a semi-sitting

position (40° off the horizontal) with a rolled towel under the

ipsilateral scapula. The shoulder should be freely mobile. A Mayo

stand, padded with a pillow, next to the operating room table

facilitates resting the shoulder in abduction and external rotation.

Drape the arm free. Overwrap the stockinet on the hand and forearm to

facilitate control of the arm. -

Locate the deltopectoral groove. In an

obese patient, this groove is located by internal and external rotation

of the shoulder. Start the incision at the clavicle just medial to the

coracoid, and extend it distally along the deltopectoral groove to the

deltoid insertion for approximately 15 cm. -

Develop skin flaps to expose the deep

fascia. Open the fascia over the deltopectoral groove with blunt

scissors, looking for the cephalic vein. This vein serves as an

important landmark for identifying the avascular interval between the

deltoid and pectoralis major muscles. Bluntly develop this interval,

and retract the deltoid laterally and the pectoralis major medially.

The vein can be ligated or retracted with the deltoid. -

In the proximal wound, incise the

clavipectoral fascia arising over the coracoacromial ligament, and

identify and coagulate the underlying acromial branch of the

thoracoacromial artery. The anterior circumflex vessels lie in the

middle of the wound, just superior to the pectoralis major muscle; they

may need to be isolated, clamped, and coagulated. -

Retracting the coracobrachialis and short

head of the biceps medially with a broad retractor protects the

axillary neurovascular bundle. Detachment of the anterior deltoid

muscle from the clavicle should be avoided if at all possible, because

it usually weakens the anterior deltoid. If detachment is necessary,

carefully elevate a flap of tendon superiorly and inferiorly off the

clavicle for resuturing the deltoid, or detach the deltoid by removing

a small wafer of bone and reattaching it with drill holes later. For

extensive proximal humerus procedures, detach the deltoid insertion off

its tubercle distally and reflect the deltoid superiorly. This provides

excellent exposure. Repair of the deltoid is simplified by suturing it

to the origin of the brachialis with interrupted figure-eight sutures. -

If better exposure of the rotator cuff is

necessary, resection of the coracoacromial ligament and an anterior

acromioplasty as described by Neer (7)

facilitates exposure. The anterior joint capsule can be exposed by

releasing the subscapularis tendon. This is facilitated by passing a

curved hemostat from distal to proximal in the interval between the

tendon and the anterior joint capsule, exiting between the

subscapularis and the supraspinatus. Because the tendon and capsule

blend together near the humeral insertion of the tendon, cut it 2.5 cm

medial to its humeral insertion. After the tendon is released, tag it

with a nonabsorbable suture to ensure easy identification when it is

reattached. -

If exposure of the axillary neurovascular

structures is necessary, incise and reflect medially the humeral

insertion of the pectoralis major. Identify the loose fascia overlying

the short head of the biceps and coracobrachialis. Incise this fascia

medially over the coracobrachialis muscle 3.5 cm distal to the coracoid

to avoid cutting its innervation from the musculocutaneous nerve.

Develop the interval medial to the biceps and coracobrachialis muscles,

and reflect these muscles laterally to expose the neurovascular bundle. -

Wider exposure is possible if the muscle

origins from the coracoid are transected. If more proximal exposure is

needed, it may be necessary to transect the origin of the pectoralis

minor muscle. A more comprehensive exposure for total shoulder

arthroplasties is described in the article by Neer et al. (9).

In such cases, release the origins of the coracobrachialis and the

short head of the biceps from the tip of the coracoid, leaving a cuff

on the tip of the coracoid for repair. Leave the pectoralis minor

intact. Retraction medially must be gentle to avoid injury to the

musculocutaneous nerve.

is useful for exposing the anterior shoulder for recurrent shoulder

dislocations if a more cosmetically acceptable scar is desired (4). The exposure, however, may be restricted in a patient with well-developed musculature.

|

|

Figure 1.3. Leslie and Ryan’s axillary exposure.

|

-

With the patient’s arm at his side,

identify the superior aspect of the anterior axillary fold. From this

point, make an incision 7 cm inferiorly into the axilla. Because the

skin and subcutaneous tissue are quite mobile in this area, extensive

undermining above the deep fascia is possible for exposure of the

deltopectoral groove. -

The rest of the surgical exposure is as described previously

P.6

in the section on Henry’s Anterior Approach.

Exposure can be facilitated by extending the skin incision proximally

to the tip of the coracoid. This approach is identical to Henry’s

anterior approach, with the exception of the limited skin incision.

-

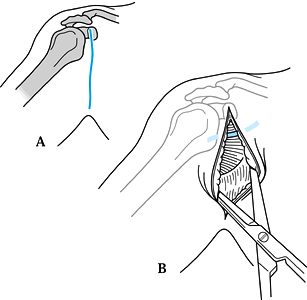

Start the incision over the

acromioclavicular joint, and extend it 8 cm inferiorly along the

anterior deltoid, just lateral to the deltopectoral groove. -

After mobilizing skin flaps, identify the

clavicular attachment of the deltoid. Detach only as much of the

deltoid as necessary for exposure, using the technique as described

under Henry’s Anterior Approach. -

Incise the underlying subacromial bursa

to expose the rotator cuff. Internal and external rotation of the

shoulder help to further visualize the anterior and posterior portions

of the cuff.

|

|

Figure 1.4. Lateral deltoid splitting exposure.

|

-

Make a transverse incision approximately

6 cm long, starting 2.5 cm inferior to the lateral tip of the acromion.

This gives a more cosmetic scar than a vertical incision. -

Undermine the skin flaps, and bluntly

incise the deltoid muscle parallel to its fibers from the tip of the

acromion superiorly to 4 cm inferiorly. Branches of the axillary nerve

course transversely, approximately 5 cm inferior to the tip of the

acromion; avoid cutting them. -

Expose the subacromial bursa in the floor

of this exposure. Incise the bursa and expose the underlying rotator

cuff. Rotation and abduction of the shoulder exposes most of the

rotator cuff in the operative field. Additional exposure of the rotator

cuff is facilitated by detaching the lateral one third of the deltoid

from the acromion and performing an anterior acromioplasty. Refer to

Henry’s Anterior Approach for a complete description.

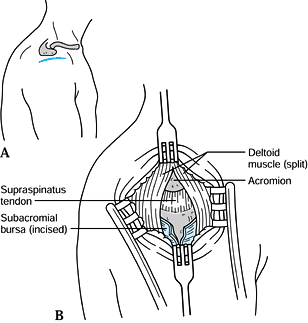

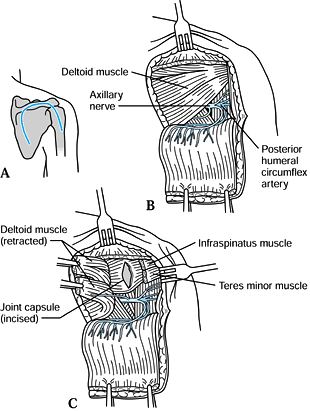

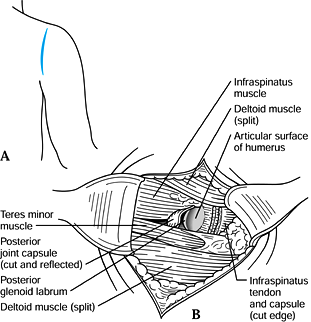

necessary for posterior shoulder instability, dislocation, glenoid

osteotomy, or soft tissue tumor. Two posterior surgical exposures may

be used. The posterior inverted U approach described by Abbott and

Lucas (1) detaches the deltoid from the scapular spine, and the other exposure splits the deltoid parallel to its fibers.

|

|

Figure 1.5. Abbott and Lucas inverted U approach.

|

-

Begin the incision parallel to the medial

border of the posterior deltoid muscle and extend 5 cm superiorly to

the spine of the scapula. Continue along the subcutaneous border of the

spine to the acromion laterally. -

Extend the incision inferiorly 7.5 cm to

the humeral head along the posterior and middle deltoid interval. By

blunt dissection, medially expose the posterior border of the deltoid,

and laterally expose the interval between the posterior and middle

deltoid fibers. -

Free the deltoid origin by subperiosteal

dissection from the scapular spine and reflect the skin and muscle flap

inferiorly, exposing the infraspinatus and the teres minor muscles and

the quadrangular space. -

The capsule can now be exposed by

splitting the interval between the infraspinatus and the teres minor

muscle medial to the conjoined tendon (sometimes this interval is

difficult to find initially). Better exposure can be gained by

detaching 1 cm of the infraspinatus tendon insertion and reflecting it

superiorly. The suprascapular nerve innervates this muscle below the

scapular spine, so be careful with its retraction.

|

|

Figure 1.6. Posterior exposure.

|

-

Locate the posterior glenohumeral joint

by rotating the shoulder. The “soft spot” superior to the posterior

axillary line helps to identify the joint. Start a vertical incision

superiorly at the spine of the scapula and extend it inferiorly 6–7 cm,

parallel to the posterior axillary line. Undermine the skin flaps

medially and laterally. -

Bluntly split the deltoid parallel to its

fibers to expose the infraspinatus and teres minor portions of the

rotator cuff. The axillary nerve passes through the quadrangular space

beneath the teres minor to innervate the deltoid. In the posterior

deltoid, therefore, this nerve is located more inferiorly than in the

lateral deltoid. -

Develop the muscle interval between the

infraspinatus and the teres minor. This interval is located medial to

the conjoined insertions at the humeral neck. Avoid dissecting into the

infraspinatus muscle to protect its innervation from the suprascapular

nerve. -

Detach part of the infraspinatus tendon

off of the joint capsule, leaving a stump of tendon for later

reattachment. Retraction of the infraspinatus superiorly and the teres

minor inferiorly exposes the posterior joint capsule. Greater exposure

can be obtained by detaching more of the infraspinatus or part of the

teres minor. Avoid excessive retraction of the teres minor to prevent

traction injury to the axillary nerve.

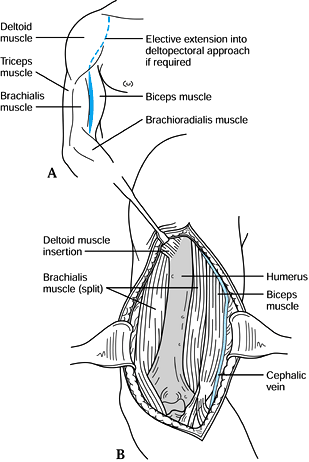

-

Identify the interval between the biceps and the brachialis by grasping and moving the mobile biceps muscle medially (Fig. 1.7).

Incise the skin just lateral to the border of the biceps 8 cm proximal

to the elbow flexion crease, and continue distally, crossing the elbow

flexion crease if needed. This exposure is extensile and can be carried

to the shoulder as needed using the deltopectoral interval. Figure 1.7. Henry’s anterolateral exposure.

Figure 1.7. Henry’s anterolateral exposure. -

While protecting the cephalic vein,

retract the biceps medially to expose the brachialis covering the

distal anterior one half of the humerus. The shaft of the humerus is

exposed by blunt dissection through the brachialis muscle in an oblique

direction from proximal lateral to distal anterior. Do not sever the

cutaneous branches of the musculocutaneous nerve crossing over the

brachialis muscle distally. The radial nerve can be identified, if

necessary, by splitting the brachialis muscle 1 cm distal and

posterolateral to the deltoid insertion. Otherwise, the radial nerve is

protected by the brachialis muscle reflected laterally. -

Wider exposure of the humerus can be

achieved by flexing the elbow, which relaxes these muscles. If more

proximal exposure is needed, refer to Henry’s anterior shoulder

approach described previously. If more distal exposure is required,

refer to Henry’s anterior elbow exposure described later in this

chapter. -

In nonunions, full exposure of the radial

nerve may be necessary before safe exposure of the bone is possible. In

this case, undermine the skin anteriorly and posteriorly over the

distal arm. Identify the interval between the brachialis and

brachioradialis. This interval can be difficult to find. The fibers of

the two muscles have slightly different degrees of coarseness and

different directions, which the surgeon can detect visually. Split

bluntly into the most distal portion of this interval; a Metzenbaum

scissors is useful. Approximately 1–2.5 cm deep into the interval,

identify the radial nerve and follow it proximally into the spiral

groove or until you are proximal to the fracture and the nerve is freed

from all scar tissue and callus.

-

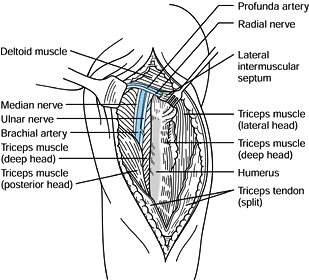

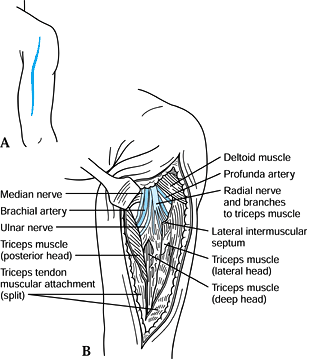

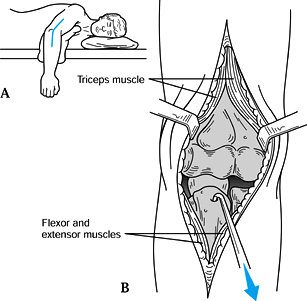

To perform Henry’s posterior exposure (Fig. 1.8, Fig. 1.9),

place the patient prone on the operating table with the upper extremity

on an arm board or on a padded gynecologic knee support. The lateral

decubitus position with the arm supported on bolsters also works well.

Identify the long head of the triceps, which is mobile and

posteromedial. Using this as a landmark, make an incision (Fig. 1.8)

3 cm inferior to the acromion, extending distally along the lateral

edge of this muscle to the olecranon if necessary. Develop the skin and

subcutaneous flaps to expose the long and lateral heads of the triceps.![]() Figure 1.8. Henry’s posterior exposure (posterior and lateral heads of triceps exposure).

Figure 1.8. Henry’s posterior exposure (posterior and lateral heads of triceps exposure). Figure 1.9. Henry’s posterior exposure (deep head of triceps exposure).

Figure 1.9. Henry’s posterior exposure (deep head of triceps exposure). -

Digitally develop the proximal interval

between these two heads of the triceps. Lift the seam from the

underlying tissue and split it distally. The distal one half of this

seam requires sharp dissection along the septum between the long and

the lateral heads. Splitting the seam (Fig. 1.9) exposes the deep head of the triceps, with the neurovascular bundles located proximally. -

Notice the relation of the radial nerve

and its branches to the three heads of the triceps. While protecting

the median nerve, ulnar nerve, and brachial artery medially, and the

radial nerve and profunda artery laterally, the deep head of the

triceps can be safely split to expose the posterior shaft of the

humerus (Fig. 1.10). Confirm that branches of

the radial nerve are identified and protected before splitting the deep

head. The radial nerve may be further visualized distally by splitting

the lateral

P.9

intermuscular

septum. To expose the radial nerve more proximally requires incising

the tendinous insertion of the teres major and latissimus dorsi.![]() Figure 1.10. Henry’s posterior humeral shaft exposure.

Figure 1.10. Henry’s posterior humeral shaft exposure.

|

|

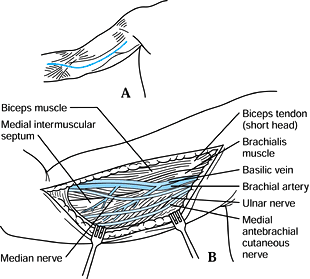

Figure 1.11. Medial exposure.

|

-

Identify the medial border of the mobile

biceps muscle. Start the incision proximally from the anterior axillary

fold to the level of the elbow flexion crease distally, following the

border of the biceps. If more distal exposure is needed, refer to the

anteromedial elbow exposure. Protect the branches of the medial

antecubital cutaneous nerve in the subcutaneous tissue. -

Starting proximally, incise the deep

fascia to expose the brachial artery, the basilic vein, and the median

and ulnar nerves. The artery, vein, and median nerve course distally,

staying anterior to the medial intermuscular septum to enter the

antecubital fossa. The ulnar nerve penetrates the intermuscular septum

at the midpoint of the upper arm, entering the posterior compartment of

the upper arm. To expose the ulnar nerve distally, incise this septum.

|

|

Figure 1.12. Lateral exposure.

|

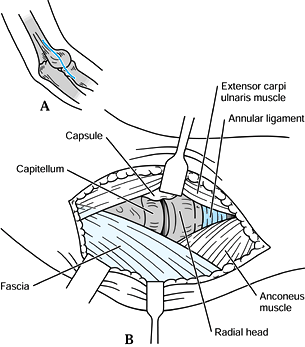

-

Pronate the forearm and flex the elbow

90° on an arm board. Identify the lateral epicondylar ridge and the

radial head by rotating the forearm. Make a gentle curvilinear incision

along the lateral epicondylar ridge 3–4 cm proximal to the joint line

and extending 3–4 cm distal to the joint along the interval between the

extensor

P.10

carpi ulnaris and the anconeus overlying the radial head. -

Proximally, reflect the triceps

posteriorly. Reflect the extensor carpi radialis longus and the

brachioradialis anteriorly. This dissection can be subperiosteal, or a

wafer of bone may be taken with the extensor carpi radialis longus

origin. -

The radial nerve passes anteriorly

between the brachialis and the brachioradialis and therefore is

protected with this proximal exposure. Distally, sharply incise the

interval between the extensor carpi ulnaris and anconeus to expose the

underlying joint capsule. Incise the joint capsule from the lateral

epicondyle to the annular ligament of the radial head. Do not extend

the incision distal to the annular ligament, because this can sever the

posterior interosseous nerve, which crosses anterolaterally across the

radial neck through the supinator muscle. Pronation of the forearm

helps to place this nerve anterior to the operative field. A smaller

incision may be used if only the radial head is to be exposed. Wider

exposure for synovectomy or other procedures is accomplished by

detaching the common exterior origin and the joint capsule from the

humerus.

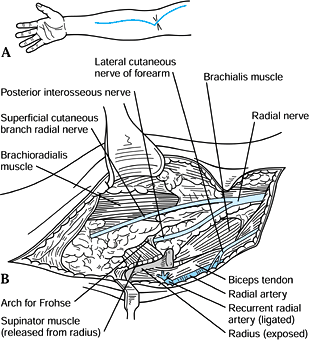

the radial nerve and the arch of Frohse, lesions of the proximal

radius, and the radial tuberosity for bicipital tendon ruptures (Fig. 1.13) (2).

|

|

Figure 1.13. Henry’s anterolateral exposure.

|

-

Position the arm with the elbow extended

and the forearm supinated. Start the incision along the lateral border

of the biceps proximally, cross the elbow flexion crease in a

curvilinear fashion, and extend the incision distally along the medial

border of the brachioradialis. The length of the incision depends on

the operative needs. If exposure of the anterior distal humerus is

needed, refer to Henry’s anterolateral humeral surgical exposure

described previously. -

Identify and preserve the lateral

cutaneous nerve of the forearm proximally in the interval between the

biceps and brachialis muscles. Identify the biceps tendon and the

lacertus fibrosis. -

For better exposure, incise the lacertus

fibrosis, flex the elbow, and pronate the forearm. Bluntly develop the

interval between the brachioradialis laterally and the pronator teres

medially to expose the radial artery. -

Identify and ligate the recurrent radial

vessels located by sliding a finger distally along the lateral edge of

the bicipital tendon. Do not cut the radial artery. -

After these vessels are ligated, the

brachioradialis can be retracted laterally to expose the radial nerve

exiting the upper arm between the brachialis and brachioradialis. The

superficial cutaneous radial nerves pass distally into the forearm

under the covering of the brachioradialis muscle. The posterior

interosseous nerve

P.11

penetrates the supinator muscle under the arch of Frohse. -

To expose the proximal radius, reflect

the origin of the supinator off the radius just lateral to the radial

tuberosity. A small bursa identifies this interval. Identification of

the radial tuberosity is facilitated by pronating and supinating the

forearm while palpating over the bicipital tendon. Do not incise

through the supinator muscle, because this action can cut a branch of

the posterior interosseous nerve.

|

|

Figure 1.14. Medial exposure.

|

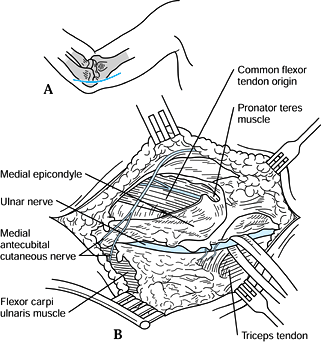

-

Place the elbow on an arm board with the

shoulder externally rotated and the elbow flexed 90°. Identify the

medial epicondyle. Start the incision approximately 4 cm proximal to

the epicondyle, and extend the incision 4 cm distally along the flexor

carpi ulnaris. -

Bluntly dissect the subcutaneous tissue and identify the branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves.

-

After these nerves are protected and the

deep fascia over the flexor-pronator muscles is exposed, palpate for

the ulnar nerve proximal to the ulnar groove. Expose this nerve by

incising its overlying fascia. -

If the nerve is to be transposed anteriorly, several principles apply:

-

The medial intermuscular septum must be incised to prevent proximal tethering of the transposed nerve.

-

The thick ligament over the ulnar groove must be incised.

-

The fascia over the flexor carpi ulnaris must be incised to prevent distal tethering of the nerve.

-

The ulnar muscular branches of the flexor carpi ulnaris may need to be exposed to facilitate the transfer.

-

Pass a 0.6 cm Penrose drain around the nerve for retraction.

-

Protect the accompanying small vessels to the ulnar nerve, if at all possible, to prevent ischemic damage to the nerve.

-

To expose the medial aspect of the elbow

joint, define the interval between the brachialis and pronator teres

anteriorly and protect the ulnar nerve posteriorly. Osteotomize the

medial epicondyle with its attached flexor pronator muscles and retract

it distally. Be careful not to retract it too vigorously, to prevent

median nerve injury. The joint capsule and medial collateral ligament

complex can be incised to expose the joint. The osteotomized bone may

be reattached with sutures or preferably with a 3–4 mm A-O cancellous

screw through a hole drilled before the osteotomy. During closure, do

not suture the deep fascia of the forearm, to prevent an iatrogenic

compartment syndrome.

-

|

|

Figure 1.15. Anteromedial exposure.

|

-

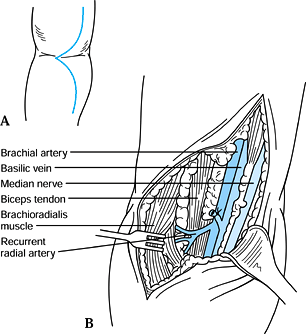

Place the arm with the elbow extended and

the forearm supinated. Start the incision proximally along the medial

border of the biceps, zigzag along the elbow flexion crease, and extend

it distally along the pronator teres. The length of the incision

depends on the operative needs. If more proximal exposure is needed,

refer to the medial humeral exposure. -

Identify the basilic vein and branches of

the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve in the subcutaneous tissue.

Incise the deep fascia proximally to expose the median nerve and

brachial artery. -

Trace these structures distally to the

level of the elbow flexion crease, where they dive under the lacertus

fibrosis. While protecting these structures, incise this fibrotic band. -

Bluntly develop the interval between the

brachioradialis and the pronator teres to expose the radial and ulnar

arteries and the median nerve. If more distal exposure of these nerves

is needed, refer to McConnell’s exposure of the median and ulnar nerves

of the forearm described later in this chapter.

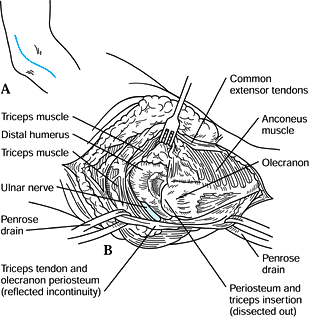

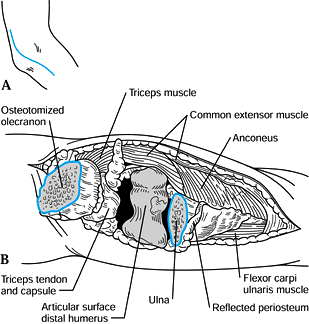

is useful for previous elbow dislocations, arthroplasty, and repair of

comminuted interarticular fracture of the distal humerus. It avoids an

olecranon osteotomy by preserving the continuity of the triceps

mechanism.

-

Position the patient in a supine position

with a rolled towel under the scapula. A sterile tourniquet may be

utilized. Make a posterior incision lateral to the olecranon 9 cm

proximal to the olecranon tip, extending it 9 cm distal to the tip. -

Create a triceps and ulnar periosteal

flap in continuity by incising the lateral border of the triceps and

extending it distally 6 cm along the ulnar shaft. -

By careful subperiosteal dissection,

reflect the triceps tendon and its periosteal attachment in continuity

toward the lateral side, preserving the ulnar collateral ligament. -

The radial head can be exposed by

including the anconeus in the subperiosteal dissection. The ulnar nerve

is protected by the soft tissues. Exposure and transfer is usually not

necessary unless it is at risk. Now the entire posterior elbow joint is

exposed (Fig. 1.16). Further exposure for arthroplasty can be obtained by releasing the joint capsule.![]() Figure 1.16. Posterolateral exposure.

Figure 1.16. Posterolateral exposure.

developed for the open reduction and internal fixation of

intraarticular fractures of the distal humerus. It has also proven

useful for reconstructive surgery, including complete posterior and

anterior release for arthrofibrosis of the elbow. It avoids olecranon

osteotomy with its potential complications and provides better exposure.

-

Position the patient in the lateral

decubitus position with the operated elbow supported on a well-padded

gynecologic knee support and flexed to 90°. Be certain that the forearm

is not obstructed, as further flexion to 110° is necessary for full

exposure of the articular surface. -

Make a longitudinal midline posterior

incision as long as necessary, staying slightly to one side of the

olecranon; full exposure requires an incision at least 20 cm in length.

Incise directly down to the deep fascia. Creation of flaps is not

necessary unless transfer of the ulnar nerve is planned. -

If transfer of the ulnar nerve is necessary, do it now, placing the nerve in a subcutaneous tunnel.

-

Split the triceps muscle in the midline,

beginning proximally and extending distally to the olecranon. Split the

joint capsule as well. -

Using a #15 blade, reflect the triceps

insertion, medially and laterally, off the olecranon in continuity with

the forearm muscles, maintaining the integrity of the retinaculum and

periosteum. Take the joint capsule in continuity with these flaps (Fig. 1.17). Figure 1.17. Chapman’s comprehensive posterior approach.

Figure 1.17. Chapman’s comprehensive posterior approach. -

With meticulous subperiosteal dissection,

reflect the lateral triceps and the forearm muscle extensor origins in

continuity, laterally, staying on bone and including the joint capsule

until the tip of the lateral epicondyle is reached. Perform the same

maneuver medially, avoiding injury to the ulnar nerve, which in most

cases can be left undisturbed in its sulcus. Include the joint capsule

in this dissection, preserving its continuity with the overlying

musculocutaneous structures. -

For complete exposure, flex the elbow to

110° and distract the olecranon with a bone hook to expose the distal

third of the humerus and its entire articular surface. With further

release, it is possible to isolate and excise the anterior capsule if

needed.

fascia, using interrupted figure-eight sutures, allows early

mobilization of the elbow joint.

|

|

Figure 1.18. Posterior transolecranon exposure.

|

-

Place the patient supine with her arm

across her chest. The skin incision is the same as that previously

described for the posterolateral approach to the elbow. Incise the deep

fascia to expose the triceps tendon and proximal olecranon. Identify

and protect the ulnar nerve medially. -

Make a 1 cm linear incision through the

triceps tendon to expose the tip of the olecranon. Predrill and tap the

olecranon for two fixation screws. Expose the medial and lateral

borders of the proximal 3 cm of the olecranon, protecting the ulnar

nerve. Before cutting the olecranon with a small oscillating saw, score

the bone at the proposed osteotomy site to ensure proper alignment

during reattachment. Cut the bone 2 cm from its tip. Use either a

transverse osteotomy, as illustrated, or a chevron osteotomy, which may

help with a more accurate reattachment. Use an osteotome to cut the

subchondral bone. -

Reflect the triceps proximally with its

attached olecranon. Release the remaining medial and lateral

soft-tissue attachments as necessary to facilitate proper exposure of

the distal intra-articular humerus. -

Perform closure by realigning the

olecranon fragment and securing it with two cancellous lag screws and

washers. An alternative method is to add a tension band wire.

-

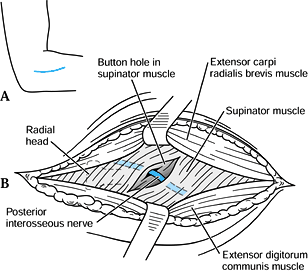

With the forearm pronated, palpate the

posterior border of the mobile wad to identify the interval between the

extensor carpi radialis brevis and the extensor digitorum communis (Fig. 1.19). Start an incision proximally, at the radiocapitellar joint line, and extend it 6 cm distally along this interval. Figure 1.19. Henry’s posterior interosseous nerve exposure.

Figure 1.19. Henry’s posterior interosseous nerve exposure. -

Develop skin flaps and incise the deep

fascia. Distally, the interval between these muscles is easily

separated and, once identified, can be split with scissors from distal

to proximal to expose the underlying supinator muscle. Avoid cutting

into the supinator muscle during this step. -

Bluntly dissect along the muscle fibers

of the supinator 3 cm distal to the radial head to expose the posterior

interosseous nerve. Rotation of the forearm at this time facilitates

locating this nerve. -

If exposure of the proximal radius is needed, incorporate this incision with the lateral exposure of the elbow (Fig. 1.12).

After the posterior interosseous nerve is safely identified, the

supinator muscle can be reflected from the ulna to expose the proximal

radius.

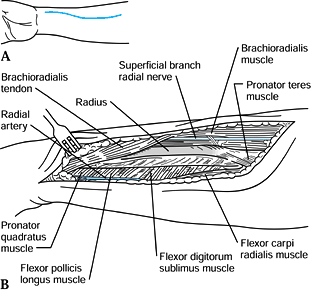

Henry’s anterolateral elbow exposure described previously and to

Thompson’s approach described later in this chapter. In its distal

third, the anterior radius is flat and can accommodate a plate better

than the convex posterior surface (Fig. 1.20).

|

|

Figure 1.20. Anterior exposure of the distal two thirds of radius.

|

-

With the forearm supinated, start a

curvilinear incision 4–5 cm distal to the elbow flexion crease along

the medial border of the brachioradialis muscle, and extend it

inferiorly toward the radial styloid. The length of the incision

depends on the exposure needed. -

Incise the deep fascia, and distally

develop the interval between the brachioradialis and the flexor carpi

radialis to expose the medial border of the radius. Protect the radial

artery, which runs in this interval, and ligate its branches if needed. -

The superficial cutaneous branch of the

radial nerve travels under the brachioradialis muscle in the proximal

two thirds of the forearm and must be identified and protected. Expose

the radius distally by reflecting the pronator quadratus and the flexor

pollicis longus subperiosteally. -

For more proximal exposure

subperiosteally, dissect the flexor digitorum sublimis and pronator

teres off the radius. Forearm pronation facilitates proximal exposure

of the pronator teres attachment.

-

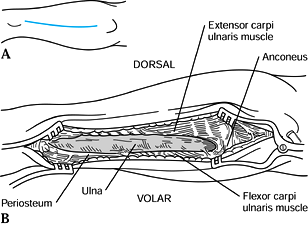

The ulnar shaft approach is facilitated by flexing the elbow and laying the arm across the patient’s chest (Fig. 1.21).

Identify the subcutaneous border of the ulna by palpation. Make a skin

incision just volar to this border. The length of the incision depends

on the surgical needs. Figure 1.21. Ulnar shaft exposure.

Figure 1.21. Ulnar shaft exposure. -

Incise the deep fascia, and distally

expose the ulnar shaft by incising the periosteum between the flexor

carpi ulnaris and the extensor carpi ulnaris. -

Subperiosteally, reflect the flexor carpi

ulnaris or extensor carpi ulnaris for volar or dorsal exposure,

respectively. To expose the shaft proximally, continue the

subperiosteal dissection between the flexor carpi ulnaris medially and

the anconeus laterally. -

Identify and protect the ulnar nerve if

the proximal ulna (olecranon) is exposed. In the distal exposure, the

ulnar nerve is safely protected if the flexor carpi ulnaris is

subperiosteally reflected.

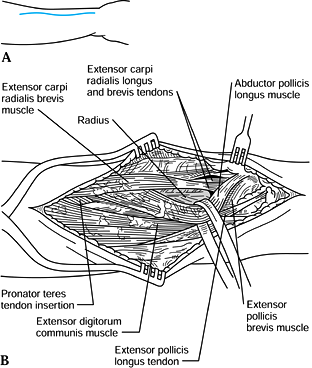

radius, refer to Henry’s exposure of the posterior interosseous nerve

described previously and to Thompson’s extended exposure described

later in this section (Fig. 1.22).

|

|

Figure 1.22. Posterior exposure of the distal two thirds of the radius.

|

-

With the forearm pronated, palpate for

the posterior border of the mobile wad to identify the interval between

the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the extensor digitorum communis.

Proximally start a curvilinear incision in this interval 5 cm distal to

the radiocapitellar joint, and extend it distally to the wrist joint

midway between the radial styloid and Lister’s tubercle. The length of

the incision depends on the surgical needs. -

Incise the deep fascia, and proximally

identify and develop the muscle interval between the extensor carpi

radialis brevis and the extensor digitorum communis to expose the

radial shaft. In the middle one third of this exposure, the abductor

pollicis longus and the extensor pollicis brevis cross the radial shaft

obliquely toward the distal radial border of the radius. These muscles

are left intact but mobilized so they can be retracted proximally and

distally as needed. -

To expose the distal radius, dissect

between the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the extensor pollicis

longus. The posterior interosseous nerve is not encountered with this

approach if the supinator muscle is not exposed and the radial shaft is

approached as described. For more proximal dissection, it is essential

to identify and protect the posterior interosseous nerve. -

In 1918, Thompson (10)

described extensions of this exposure, including exposure of the entire

radius and exposure of the posterior interosseous nerve if needed.

Follow the line of separation between the extensor digitorum communis

and the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscles up to the lateral

epicondyle of the humerus if needed. This fully exposes the supinator

muscle. Detaching the origins of these muscles from the lateral

epicondyle allows even wider exposure. By supinating the radius, the

junction of the supinator origin and the biceps tendon can be

visualized. -

Carefully dissect the supinator off the

radius, staying against bone. Expose only as much radius as necessary.

Avoid over-retraction, because a stretch injury to the posterior

interosseous nerve can result, particularly where it is tethered by the

motor branches to the extensor digitorum communis. To expose the

posterior interosseous nerve, identify it proximal to the supinator,

and trace it into the body of the supinator.

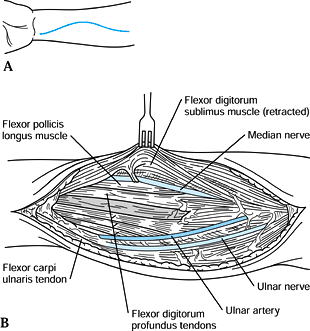

-

Place the forearm supinated on an arm

board. Proximally, start the incision near the medial epicondyle and

extend it distally in a lazy-S fashion to the radial border of the pisiform (2) (Fig. 1.23).

The length of the incision depends on the surgical needs. Protect the

medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves in the proximal forearm. Figure 1.23. McConnell’s median and ulnar nerve exposure.

Figure 1.23. McConnell’s median and ulnar nerve exposure. -

Distally, expose the ulnar artery and

nerve by incising the deep fascia along the radial border of the flexor

carpi ulnaris. Retracting the flexor carpi ulnaris ulnarly and the

flexor digitorum sublimis radially allows the ulnar artery and nerve to

be visualized and followed proximally. Flexion of the wrist helps to

relax these tendons. -

The artery and nerve run parallel until

the proximal one third of the forearm, where the artery courses toward

the antecubital fossa and the ulnar nerve continues under the flexor

carpi ulnaris to the ulnar groove. Protect the branches of the ulnar

nerve innervating the flexor carpi ulnaris and part of the flexor

digitorum profundus in the proximal forearm. -

Distally, identify the median nerve as

the flexor digitorum sublimis is reflected radially. Follow the median

nerve proximally as it lies between the sublimis and profundus muscles.

Halfway up the forearm, the median nerve is bound to the intermediate

tendinous portion of the sublimis muscle. Because the nerve is on the

radial side of this juncture, incising along its ulnar border further

exposes the nerve. -

To expose the median nerve more

proximally, identify and develop the interval between the pronator

teres and the flexor carpi radialis. Just inferior and deep to the

pronator teres lies the median nerve. Sometimes the arch of the

sublimis covers the nerve at this level, but dissecting through this

portion of the sublimis exposes the nerve.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.