Sprengel Deformity

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Sprengel Deformity

Sprengel Deformity

Paul D. Sponseller MD

Description

-

Sprengel deformity:

-

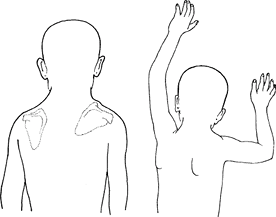

Congenital elevation of the scapula (Fig. 1)

-

Small scapula with restricted ROM

-

Often, congenital anomalies coexist.

-

-

This condition:

-

Is present from birth

-

May be discovered at birth or after the child starts to use the arms

-

Usually is diagnosed within the 1st few years of life

-

-

Surgery is best performed in patients 2–8

years old, although satisfactory results have been reported as late as

14 years of age. -

Synonyms: Undescended scapula; Congenital high scapula

Epidemiology

Incidence

Rare

Prevalence

-

<1 per 10,000 (1)

-

More common in girls than in boys, with a ratio of 3:1 (1)

Risk Factors

-

Myelomeningocele

-

Congenital cervical fusion

Genetics

-

It is almost always a sporadic condition.

-

Only a small number of familial cases have been reported (1) in which the pattern was autosomal dominant.

Fig. 1. Sprengel Deformity is an Elevated, Downward-Rotated Scapula. This Produces Limitation of Abduction (right).

Fig. 1. Sprengel Deformity is an Elevated, Downward-Rotated Scapula. This Produces Limitation of Abduction (right).

Etiology

-

The normal scapula:

-

Appears in the 5th week of embryonic life, located in the neck, opposite the C5–T1 segments

-

Migrates distally to its position in the thoracic region

-

-

Therefore, Sprengel deformity is a failure of descent of the scapula.

-

Its cause is unknown.

-

It may be secondary to defective formation or later contracture of musculature.

-

1 theory is that abnormally located “blebs” of cerebrospinal fluid interfere with scapular descent (1,2).

-

Associated Conditions

-

Klippel-Feil (cervical fusions) syndrome

-

Myelomeningocele

-

Congenital scoliosis

-

Syringomyelia

-

Renal malformations

-

Limb malformations may each occur sporadically with this condition, or Sprengel deformity may occur in isolation.

Signs and Symptoms

-

Most commonly unilateral, but may be bilateral

-

The scapula:

-

Small and elevated

-

Rotated so the glenoid faces more

downward than normal, placing the inferomedial pole closer to the spine

and the superomedial pole farther from it -

The superomedial pole is prominent in the base of the neck.

-

-

The angle of the neck on affected side may appear more blunted than that on the opposite side.

-

Variation occurs in the degrees of severity, from obvious to barely noticeable deformity.

-

Abduction of the arm is limited because the glenoid is turned downward and because the motion of the scapula is decreased.

-

Causes the patient to tilt the trunk when reaching upward; this motion often is the 1st to bring the diagnosis to light.

-

Physical Exam

-

Note the prominence of the scapula in the angle of the neck from anterior and posterior aspects.

-

Palpate the superomedial aspect of the scapula to check for a bony connection (omovertebral bar) to the spine.

-

Measure the ROM, especially abduction (raising up to side).

-

Check neck ROM.

-

Perform the spine-bending test to look for scoliosis.

-

If the patient has congenital cervical fusions, test the hearing because an increased risk of hearing abnormalities is possible.

Tests

Lab

Test results are normal.

Imaging

-

Radiography:

-

On the cervical spine, look for associated congenital anomalies.

-

On the thoracolumbar spine, rule out scoliosis.

-

-

In addition, ultrasound of the kidneys, ureter, and bladder is indicated because of the high incidence of associated anomalies.

Pathological Findings

-

Scapula:

-

Smaller than normal

-

May be attached at its upper portion to

the spinous processes of the lower cervical or upper thoracic spine by

a bar of bone or cartilage known as an omovertebral bar -

Upper portion is curved abnormally forward.

-

The muscles that normally attach the scapula are hypoplastic.

-

-

Multiple other congenital malformations of other systems may be associated, in random fashion.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Congenital cervicothoracic scoliosis may

distort the trunk and ribs, thus giving an appearance similar to that

of Sprengel deformity. -

Birth palsy of the upper portion of the

brachial plexus may cause an inability to abduct the extremity, so use

of the arm resembles that of a patient with Sprengel deformity. -

Injury to the axillary nerve, such as

after a shoulder dislocation, produces deltoid-muscle weakness, with

inability to abduct the shoulder. -

Injury to the long thoracic nerve produces winging of the scapula.

-

Fascioscapulohumeral dystrophy produces bilateral shoulder weakness.

P.421

General Measures

-

Stretching and strengthening are recommended initially, but it is doubtful whether they make any major improvement.

-

During these early years, the patient

should be observed to determine the degrees of visibility of the

deformity and its impact on the function of the arm. -

Problems in these areas are indications for surgery.

Activity

-

Parents or physicians should not restrict activity.

-

Often, these children are surprisingly functional.

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

-

Physical therapy is useful in nonoperative cases to improve the range of abduction.

-

Active and passive stretching exercises, to be maintained by the parents

-

-

The family can assess whether the results over the first 2–4 years of the patient’s life are satisfactory.

Surgery

-

For patients who are unwilling to accept

the degree of deformity or limitation of abduction that Sprengel

deformity produces, surgical relocation of the scapula is the only

option. -

Several techniques are used to accomplish

this goal, all of which involve detaching the muscles from their

origins or insertions (2,3). -

Results:

-

Noticeable improvement, but not restoration of appearance or function to normal

-

Improved range of abduction

-

The incision on the back may tend to spread and become wider than incisions in other areas.

-

Prognosis

-

The deformity usually is static and does not improve or worsen with time.

-

No evidence indicates that it causes

arthritis of the shoulder, although the affected side may be weaker

than the contralateral side.

Complications

-

The results of surgery usually are good, but complications include:

-

Brachial plexus stretch

-

Weaknesses of the shoulder muscles

-

Incomplete correction

-

A wide incision scar

-

Patient Monitoring

-

The family should bring the child in for several visits, ~6–12 months apart, when trying to decide about surgery.

-

The best age for surgery is when the

patient is 2–8 years old, although it has been successfully done on

both older and younger patients.

References

1. Tsirikos AI, McMaster MJ. Congenital anomalies of the ribs and chest wall associated with congenital deformities of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg 2005;87A:2523–2536.

2. Cavendish ME. Congenital elevation of the scapula. J Bone Joint Surg 1972;54B:395–408.

3. Woodward JW. Congenital elevation of the scapula: Correction by release and transplantation of muscle origins. J Bone Joint Surg 1961;43A:219–228.

Codes

ICD9-CM

755.52 Sprengel deformity

Patient Teaching

-

Parents should be:

-

Shown the normal and abnormal positions of the clavicle

-

Told that stretching results in slight improvement, and surgery results in a good deal more

-

Informed about the length of the surgical incision

-

FAQ

Q: Is surgery mandatory for Sprengel deformity?

A: It is not mandatory if the appearance of the shoulder and the degree of abduction are acceptable to the patient.