RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS OF THE FOOT

Women are affected more frequently than men, with a peak onset noted in

the third to fifth decade. Rheumatoid arthritis affects both small and

large joints in the upper and lower extremities. Although its onset is

typically insidious, an acute presentation is not uncommon. Chronic

inflammatory changes of rheumatoid arthritis can cause significant

disability of the foot. Initial involvement of the feet is noted in 16%

of patients with acute manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis; however,

the incidence of chronic foot deformities in patients with longstanding

rheumatoid arthritis may approach 90% (65,89).

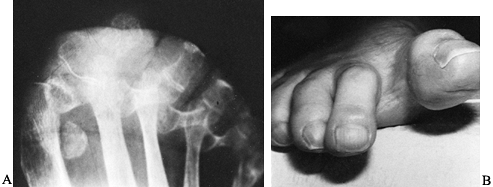

In chronic rheumatoid arthritis, symmetric involvement is frequently

reported, although early involvement may be asymmetric. Because of

chronic inflammatory synovitis, the metatarsophalangeal joints become

distended. This eventually leads to the loss of integrity of both the

collateral ligaments of the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints and the

supporting capsular structures, which sets the stage for progressive

deformity due to loss of stability.

characterized by erosion of the metatarsal heads with cystic

degeneration. As a patient continues to ambulate in the presence of

incompetent ligamentous and capsular structures, subluxation and

eventual dislocation can occur at the MTP joints (17).

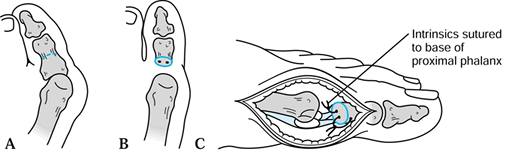

In the presence of an active synovitis, the intrinsic muscles are

overpowered by the extrinsic flexor and extensor muscles, and clawing

of the interphalangeal (IP) joints and dislocation of the MTP joints

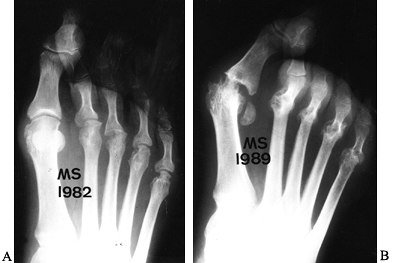

can occur (Fig. 117.1). This clawing leads to a

distal displacement of the plantar fat pad and the formation of

intractable plantar keratoses beneath prominent metatarsal heads (Fig. 117.2).

Marked rigidity of the foot due to ankylosis of the ankle, hindfoot, or

midfoot makes the foot less supple, which compounds forefoot symptoms.

|

|

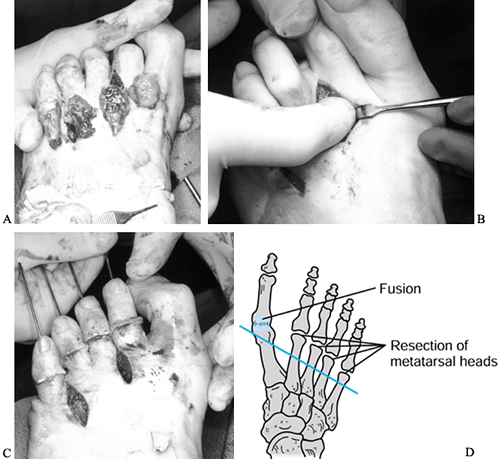

Figure 117.1. A: Rheumatoid arthritis with dislocated third metatarsophalangeal joint and chondrolysis of remaining lesser MTP joints. B: Seven years later, severe hallux valgus with dislocation of the second, third, fourth, and fifth MTP joints has occurred.

|

|

|

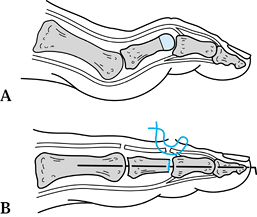

Figure 117.2. A: Normal anatomy of the lesser toe. B:

Pathophysiology of lesser toe deformity in rheumatoid arthritis. (From Coughlin M. The Rheumatoid Foot. Pathophysiology and Treatment of Arthritic Manifestations. Postgrad Med 1984;75:207, with permission.) |

that the forefoot had the greatest propensity for involvement with

longstanding rheumatoid arthritis. Michelson et al. (65)

observed that within the first 3 years following the onset of

rheumatoid arthritis, two thirds of patients developed MTP synovitis.

McGarvey and Johnson (63) and Spiegel and Spiegel (84) reported that approximately two thirds of patients with

chronic rheumatoid arthritis develop subluxation and dislocation of the

lesser MTP joints. Hammer-toe or claw-toe deformities of the lesser

toes vary in frequency from 40% to 80% (63,65,89,93).

As progressive clawing of the lesser toes develops, little stability is

afforded to the great toe, and gradual lateral migration occurs either

beneath or above the second and third toes. This is associated with

progressive articular destruction and resorption of subchondral bone,

which destabilizes the great toe MTP joint. With progressive deformity,

active weight bearing on the first ray lessens and a greater proportion

of weight is borne beneath the lesser metatarsal heads (Fig. 117.3).

|

|

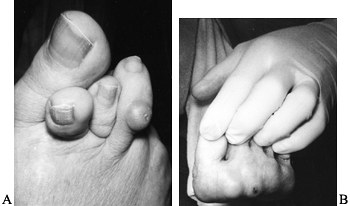

Figure 117.3. A: A typical rheumatoid foot showing severe hallux valgus and overlapping and clawed lesser toes. B:

The plantar surface of a foot, demonstrating prominent metatarsal heads, distal migration of the metatarsal fat pad, and an intractable plantar keratosis beneath the second metatarsal head. C: Postoperative appearance after the first metatarsophalangeal joint fusion and a resection arthroplasty of the lesser MTP joints with hammer-toe repairs. D: Postoperative photograph of the plantar aspect of the foot, demonstrating improved position of the foot and toes with resolution of the intractable plantar keratoses. |

forefoot was involved 10 times more frequently than the hindfoot in

patients with chronic rheumatoid arthritis. Vidigal et al. (93)

noted that two thirds of patients with chronic rheumatoid arthritis

developed mid tarsal involvement, associated with flattening of the

longitudinal arch in approximately 50% of patients. Often a valgus

deformity of the hindfoot occurs in association with this, leading to a

shuffling, flat-footed gait, and with the passage of time, the foot

changes to a passive weight-bearing platform for ambulation.

Chondrolysis associated with chronic synovitis eventually may lead to

tarsometatarsal joint involvement. Likewise, the

first

metatarsocuneiform joint may develop hypermobility with resultant

impaired gait. Transfer metatarsalgia may occur in association with

this first-ray hypermobility. Vainio (89)

noted that 59% of men and 72% of women with chronic rheumatoid

arthritis developed either midtarsal or hindfoot arthritis. Typically,

hindfoot degeneration occurs much later with chronic rheumatoid

arthritis. Spiegel and Spiegel (84) reported

that in patients with rheumatoid arthritis of a duration less than 5

years, only 8% developed arthritis of the hindfoot; however, of those

with a duration greater than 5 years, 25% developed symptomatic

hindfoot arthritis. Gold and Bassett (32) reported that

the talonavicular joint is typically the first hindfoot joint to become involved, and Michelson et al. (65)

reported that degenerative subtalar changes varied in incidence from

32% to 42%. As with the forefoot, the underlying pathophysiology is the

destruction of the capsule and ligaments supporting the joints combined

with concomitant progressive arthritis. Because the function of the

subtalar joint is directly associated with transverse tarsal joint

function, overall instability and deformity of these joints may lead to

altered gait and function with a progressive pes planovalgus deformity.

Likewise, posterior tibial tendon dysfunction can lead to a progressive

unilateral flat-foot deformity (25,45).

With the development of a severe hindfoot deformity, an Achilles tendon

contracture may develop. Thus, at the time of corrective surgery,

lengthening of the Achilles tendon may be necessary.

noted that 63% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis of less than 10

years’ duration developed ankle synovitis. Benson and Johnson (7) and others (73,89,93)

have reported the ankle joint to be involved with a frequency of 4% to

16%. Clearly, hindfoot involvement occurs much more frequently than

involvement of the ankle joint (Fig. 117.4). Wagner (94)

reported on 8,000 clinic visits to Rancho Los Amigos Hospital by

patients with arthritis; in this group, 90 ankle arthrodeses were

performed. Only three ankle arthrodeses were performed for patients

with rheumatoid arthritis. Thus, a very small percentage of patients

had rheumatoid arthritis of the ankle and progressed to surgery.

|

|

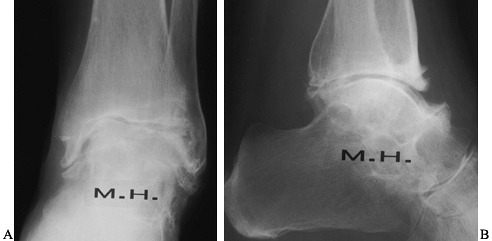

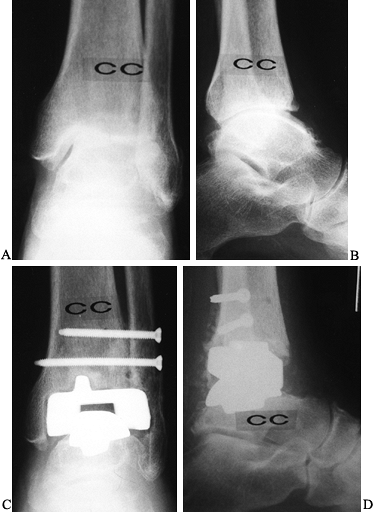

Figure 117.4. Anteroposterior (AP) (A) and lateral (B) radiographs demonstrating ankle arthritis and spontaneous subtalar fusion in a patient with longstanding rheumatoid arthritis.

|

inflammatory arthritis are ill-defined metatarsalgia and forefoot pain.

These complaints are often associated with synovitis and concomitant

intra-articular effusions that impair ambulation. Although ill-defined

metatarsalgia may be misdiagnosed as an interdigital neuroma (90),

in time chronic synovitis may make a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis

more obvious. In the presence of forefoot problems, as time passes

synovitis usually develops. Findings include nonspecific forefoot

edema, swelling, tenderness to palpation, and impaired ambulation. In

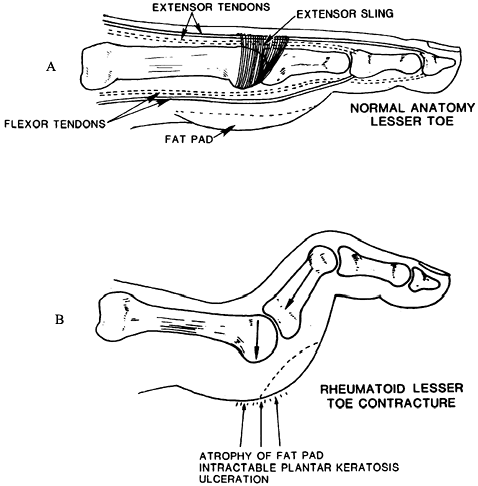

time, a hallux valgus deformity, subluxation or dislocation of the

lesser MTP joints, and fixed hammer-toe or claw-toe deformities may

develop (Fig. 117.5). Note any hindfoot

deformities and especially posterior tibial tendon dysfunction, pes

planovalgus, and Achilles tendon contracture.

|

|

Figure 117.5. A:

Dorsal view of a foot with longstanding rheumatoid arthritis, with hallux valgus and subluxation of the lesser toes and hammer-toe deformities. B: Severe intractable plantar keratoses associated with dislocation of the lesser metatarsophalangeal joints. |

typical of synovial inflammatory diseases associated with hyperemia,

periarticular osteoporosis, and soft-tissue swelling. In time, marginal

cortical erosions may develop

that

then progress to central erosions, joint-space narrowing, and eventual

joint subluxation and dislocation as destruction of the articular

cartilage develops. Rheumatoid arthritis tends to involve the first,

fourth, and fifth metatarsal joints early on (32),

specifically the medial aspect of the first, second, third, and fourth

metatarsals and the lateral aspect of the fifth metatarsal. The IP

joints of the toes are typically not involved except for the hallux.

Hindfoot and midfoot deformities include midfoot collapse, pes planus,

and subtalar sclerosis. Look for involvement of the knee and hip

joints, because in general, involvement of these joints requires total

joint arthroplasty before reconstructive foot surgery (20).

|

maintaining a good gait pattern and independent ambulation, or

restoring adequate gait by minimizing inflammation, reducing pain, and

supporting inflamed joints. In the presence of fixed deformity,

surgical correction may be necessary, with arthrodeses and occasional

excisional arthroplasty being the preferred treatments.

swollen and inflamed joints of an acute rheumatoid flare-up.

Application of a cast may be necessary. Roomy footwear, padding, and

prefabricated or custom longitudinal arch supports may be efficacious.

An important aspect of nonsurgical care involves proper shoes and the

modification of shoes. A metatarsal pad placed proximal to an area of

plantar keratoses may diminish tenderness and relieve discomfort

associated with increased pressure. Many patients with early rheumatoid

foot deformities can be adequately treated with a soft-soled and

broad-toed shoe (85). An in-depth shoe with a

custom-molded, a viscoelastic, or a soft insole may help to accommodate

progressive deformities. Working with a pedorthist with skill in the

use of specialized orthopaedic appliances helps to maintain function

and prevent deformities. Orthotic devices help redistribute plantar

weight-bearing forces, which may decrease discomfort associated with

pressure areas, and support unstable joints. Shoes with low heels,

increased depth, and soft leather uppers may be used to accommodate

hammer-toe and claw-toe deformities. A soft-soled rocker-bottom shoe is

helpful in the treatment of not only metatarsalgia but hindfoot

deformities.

how to look for potential breakdown areas in their skin. Patients with

hindfoot and midfoot discomfort with minimal or no deformity can be

adequately treated with a custom arch support or a polypropylene ankle

or foot orthosis. As deformities increase, custom bracing may alleviate

discomfort and provide support. A molded leather ankle lacer with steel

stays can be used inside a shoe and provides significant hindfoot and

ankle support. With progressive deformity or deformity associated with

unrelenting

pain

refractory to conservative treatment, surgical intervention for

forefoot, midfoot, or hindfoot dysfunction may be indicated.

to maintain or attain a plantigrade foot. The clinical course of a

patient’s rheumatoid arthritis determines the treatment program. Direct

treatment toward correction of deformity, restoration of function, and

pain relief. Pharmacologic treatment is an essential part of

controlling the disease process, and involvement of a rheumatologist

for medical management is most important. Rheumatologists often

prescribe salicylates, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, gold

salts, antimalarials, and immunosuppressive agents for the treatment of

inflammatory arthritis, with the goals being reduction of inflammation

and relief of pain. An occasional intra-articular corticosteroid

injection may be helpful, but oral steroid therapy is employed less

commonly because of the deleterious side effects associated with

chronic use (24). I recommend that methotrexate

be discontinued 1 week before and 1 week after surgery to avoid the

diminished wound-healing capacity often associated with it. See Chapter 99

for more details on medical management. Cover patients who had previous

total joint arthroplasty with perioperative antibiotics at the time of

foot and ankle surgery.

forefoot and hindfoot deformities associated with rheumatoid arthritis.

Stretching exercises for contracted Achilles tendon, manipulation of

ankle and hindfoot joints to maintain or restore range of motion,

muscle-strengthening exercises to assist in maintaining ambulatory

capacity, and the use of ambulatory aids such as crutches, walkers, and

canes may help in maintaining ambulation. With upper extremity

involvement, platform crutches or canes may be necessary. Reduced

ambulation during acute flare-ups, and stretching and exercises for

involved joints are important elements of a physical therapy regimen to

help maintain function in the patient with progressive rheumatoid

arthritis.

throughout the progression of the rheumatoid disease process, surgical

intervention depends on the progression of the disease process and its

severity. Individualize the timing of specific surgical procedures for

each patient. Although sometimes conservative management provides

relief of pain, making surgical intervention unnecessary, a synovectomy

may be indicated to slow the progression of the inflammatory process.

With increasing deformity, the ultimate goal is to prevent the loss of

capacity to ambulate that may occur with progression of the arthritis.

Surgical intervention may be interspersed with long periods of

conservative care. In general, proximal joint surgery (total hip and

knee arthroplasty) should precede foot and ankle surgery. Hindfoot

surgery typically precedes forefoot surgery (22).

The rationale for hindfoot surgery preceding forefoot surgery is that

with a progressive pes planus deformity, a recurrent forefoot deformity

may occur. I prefer to operate on one foot at a time, because the

magnitude of surgery may diminish ambulatory capacity in the

postoperative period.

the treatment of painful joints early in the disease process, before

significant deformity has occurred (2,11,23,24,74,90).

This procedure is contraindicated in the presence of MTP joint

subluxation or dislocation, or with the formation of intractable

plantar keratoses; in these cases, it achieves limited gains. Excision

of hypertrophic synovial tissue may slow or arrest the degenerative

process, decrease distention of MTP joints, and reduce the soft-tissue

deformation that would lead in time to subluxation and dislocation.

Success of surgery depends on the length of remission, but a patient

should be informed that a synovectomy may provide only temporary

relief. Nonetheless, it helps to maintain function of the lesser MTP

joints and toes.

-

Center a dorsal longitudinal incision

over the involved MTP joint. With multiple joint synovectomies, use a

second and/or fourth interspace incision to expose adjacent joints. -

Using the extensor tendon as a guide,

carry the dissection down through the extensor hood and incise the

capsule, exposing the MTP joint. -

Resect proliferative synovial tissue on

the medial and dorsolateral aspects, taking care to remove any synovium

beneath the collateral ligaments. Carry the resection as far in the

plantar direction as possible. -

Close the joint capsule with absorbable sutures, and approximate the skin with interrupted sutures.

-

Carry out a synovectomy of the first MTP

joint through a dorsal longitudinal incision centered over it, using a

technique similar to that described for the lesser MTP joints.

and change it weekly for 6 weeks. Initiate active and passive MTP

range-of-motion exercises 3 weeks after surgery.

have reported good pain relief following synovectomy. Major

complications include injury to the dorsal cutaneous nerve of the

lesser toes. Take care to avoid injury to adjacent sensory nerves. In

time, recurrence of synovial hypertrophy may lead to symptoms and

require further surgery.

hammer-toe and claw-toe deformities that occur in association with MTP

subluxation and dislocation. Whereas a mild deformity may be treated

with passive manipulation and intramedullary Kirschner wire (K-wire)

fixation (closed osteoclasis) (14,23,49,60,70), more severe deformities need a proximal phalangeal condylectomy to achieve realignment with bony decompression (22,23,43,49,95).

-

Center an elliptical incision over the dorsal proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint of the lesser toe (Fig. 117.6). Excise the dorsal callus, extensor tendon, and joint capsule, exposing the PIP joint.

Figure 117.6. Hammer-toe repair. A: Resection of the distal condyle of the proximal phalanx. B: Use of an intramedullary K-wire to stabilize the arthroplasty site.

Figure 117.6. Hammer-toe repair. A: Resection of the distal condyle of the proximal phalanx. B: Use of an intramedullary K-wire to stabilize the arthroplasty site. -

Sever the collateral ligaments on the

medial and lateral aspects, allowing the condyles to be delivered into

the wound. Take care to avoid injury to the adjacent neurovascular

bundles. -

Resect the condyles of the proximal

phalanx in the supracondylar region, and smooth them with a rongeur. As

the toe is brought into correct alignment, if there appears to be any

remaining tension at the PIP joint, resect more bone. You may resect

the articular surface of the base of the middle phalanx with a rongeur

to achieve arthrodesis, but this is optional. -

To stabilize the arthroplasty, introduce

a 0.045 K-wire at the PIP joint, and drive it distally to exit the tip

of the toe. With the toe aligned, drive the pin in a retrograde

fashion, stabilizing the repair. -

If MTP joint arthroplasty is also done,

advance the pin into the metatarsal shaft, stabilizing the arthroplasty

site. Although the use of an intramedullary K-wire to stabilize the PIP

arthroplasty site is a matter of preference, internal fixation appears

to improve the cosmetic result by achieving and maintaining alignment

postoperatively (33,52,59,95).

days. Remove sutures and K-wires 3 weeks after surgery, and support the

toes with a gauze-and-tape dressing for 3 more weeks. Discontinue

dressings 6 weeks after surgery. Avoid constrictive shoe wear for at

least 3 months following surgery.

patients with rheumatoid arthritis have been reported, the goal of

treatment is to achieve and maintain adequate alignment of the lesser

toes. The major complication following surgery is recurrence of

deformity, which in time may lead to hyperextension of the MTP joint.

Recurrent deformity may be due to a lack of initial correction or to

true recurrence. Other complications include prolonged swelling, which

usually subsides in time; molding of the toe to the shape of the

adjacent toes; and, on occasion, a painful arthroplasty site, for which

injection with corticosteroids often gives lasting relief.

rheumatoid arthritis associated with hallux valgus, metatarsalgia, and

subluxation/dislocation of the lesser MTP joints. The choices of

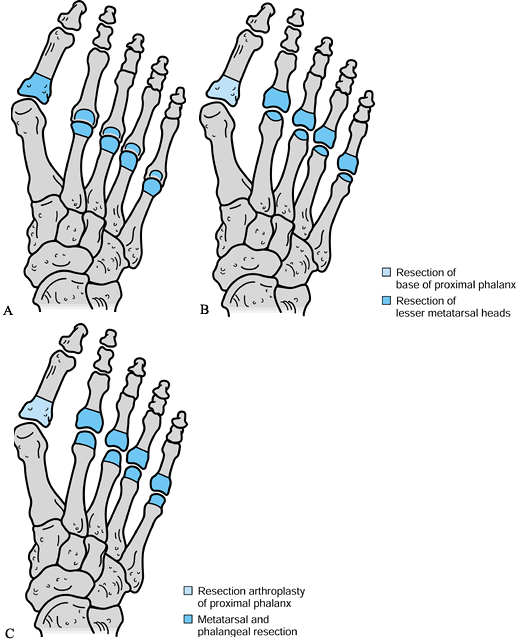

techniques include a Hoffman procedure (metatarsal head excision) (Fig. 117.7A) (38), a Fowler procedure (resection of the base of the proximal phalanx with beveling of the plantar metatarsal surface) (Fig. 117.7B) (30), and a Clayton procedure (partial proximal phalangectomy combined with metatarsal head resection) (Fig. 117.7C) (13,14 and 15).

The choice of operative incisions depends on your preference. A

transverse plantar incision, an elliptical plantar incision with

resection of redundant skin and soft tissue, a transverse dorsal

incision, and multiple longitudinal dorsal incisions are all

alternatives (Fig. 117.8). I prefer three

longitudinal dorsal incisions, with the medial incision centered over

the first MTP joint and the two lateral incisions located over the

second and fourth intermetatarsal spaces.

|

|

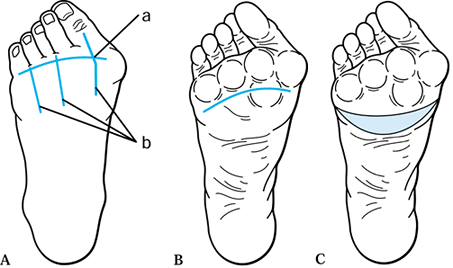

Figure 117.7. Alternatives for forefoot arthroplasty. A: Hoffman procedure. B: Fowler procedure. C: Clayton procedure.

|

|

|

Figure 117.8. Operative incisions. A: (a) Transverse dorsal incision. (b) Longitudinal dorsal incisions. B: Transverse plantar incision. C: Elliptical plantar incision.

|

and a decision must be made as to whether an entire forefoot

arthroplasty should be performed. If one or two joints are involved, an

arthroplasty may be performed on only these joints. However, alert the

patient that the disease process will likely progress in time,

eventually involving the other MTP joints. Rarely is the first MTP

joint spared when the other lesser metatarsal joints are involved. When

the entire forefoot is involved except for the fifth MTP joint, perform

an arthroplasty of the fifth MTP joint as well. Whereas Thomas (85)

recommended surgical resection for a single involved MTP joint, he

recommended that an entire forefoot arthroplasty be performed if three

joints were involved. Marmor (62) and others (9,52,66,72)

recommended that an entire forefoot arthroplasty be performed when two

MTP joints required resection. I support this procedure because it

frequently eliminates the need for later additional surgery with

further involvement of the remaining MTP joints.

-

With the skin flaps slightly undermined, dissect obliquely to each side to expose the adjacent MTP joints.

-

Identify the extensor tendons, but leave them intact except in the presence of significant contracture.

-

Identify the bases of the proximal

phalanges by tracing the insertion of the long extensor tendon. Take

care to protect the neurovascular bundles. -

With sharp dissection, incise the capsule

and expose the metatarsal neck and head circumferentially. Plantar

flexion of the phalanx often delivers the metatarsal head dorsally. -

Resect redundant synovium.

-

With a bone-cutting rongeur, transect the

metatarsal in the metaphyseal region. The amount of bone resection

depends on the shortening that has occurred with the dislocation. -

Grasp and remove the metatarsal head.

Removal of the entire metatarsal head in one piece avoids leaving

remnants of bone, which may later lead to recurrent callosities. -

Bevel the plantar aspect of the metatarsal shaft to reduce any prominence. Resect any synovial cysts or bursa as well.

-

I prefer to preserve the concave surface

of the proximal phalanx (avoiding a partial proximal phalangectomy),

because I believe the base of the proximal phalanx affords significant

stability to the pseudoarticulation at the MTP joint. With

decompression of the MTP joint, I have found that in time the fat pad

routinely realigns, thereby eliminating the need for resection of the

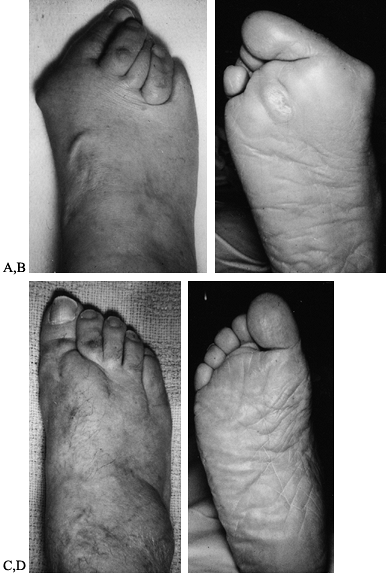

plantar skin (Fig. 117.9A). It is important

that the excisional arthroplasty of the lesser MTP joints achieve

decompression of the MTP joint; usually a space of 1 cm between the

resected metatarsal surface and the base of the proximal phalanx is

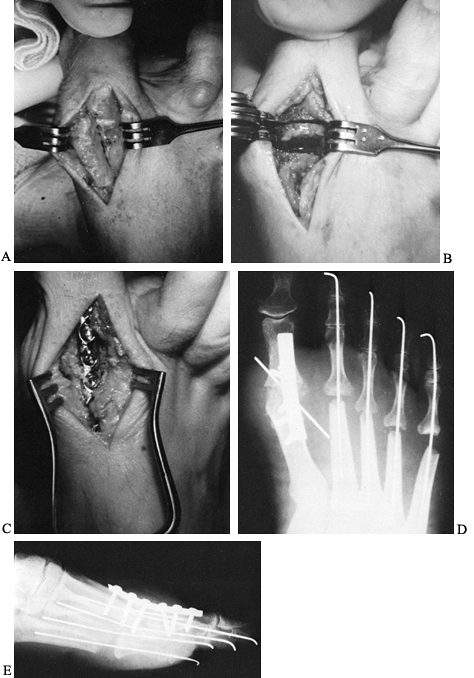

sufficient.![]() Figure 117.9. Metatarsal head resection. A: Excision of the four lesser metatarsal heads through two longitudinal intermetatarsal incisions. B: Introduction of the index fingertip into the resection site. C: Stabilization of the digits with intramedullary K-wires. D: Second and third metatarsals of equal length, and fourth and fifth metatarsals progressively slightly shorter.

Figure 117.9. Metatarsal head resection. A: Excision of the four lesser metatarsal heads through two longitudinal intermetatarsal incisions. B: Introduction of the index fingertip into the resection site. C: Stabilization of the digits with intramedullary K-wires. D: Second and third metatarsals of equal length, and fourth and fifth metatarsals progressively slightly shorter. -

With longitudinal tension on the toe,

insert the tip of your index finger into the resection arthroplasty

site and gauge the adequate amount of resection (Fig. 117.9B).

There should be room for the tip of your finger to be placed

comfortably in this interval. It is important to resect the metatarsal

heads and metaphysis symmetrically. I prefer that the first and second

metatarsals be of equal length, with the third, fourth, and fifth

metatarsals being progressively shortened from medial to lateral. This

helps to avoid an abnormally long metatarsal with consequent

development of intractable plantar keratoses. -

Following metatarsal head resection, correct hammer-toe deformities with a closed osteoclasis or an open hammer-toe repair (see Chapter 113). Introduce an 0.045 K-wire at the PIP joint and drive it in a distal direction to exit the tip of the toe (Fig. 117.9C). Advance it proximally into the metatarsal diaphyses and metaphyses.

-

Embed the K-wire in the proximal

metatarsal base to give stability to the arthroplasty site. Bend the

pin at the tip of the toe to prevent proximal migration. -

Approximate the arthroplasty sites with the skin closure (Fig. 117.9D).

Change it weekly for approximately 6 weeks. Remove K-wires and sutures

3 weeks after surgery. Allow the patient to ambulate in a wooden-soled

postoperative shoe. Immediately after surgery, observe the circulatory

status of the toes. With severe deformities, vascular compromise may

develop, necessitating removal of the K-wires.

showed 89% good and excellent results at final follow-up. Of 1,874

cases reported in many series using various surgical techniques, an

overall satisfaction rate of 81% has been reported (4,5,9,13,16,26,30,35,44,54,55,59,60,62,63,66,68,79,80,91,92,95).

|

|

Figure 117.10. A: Preoperative radiograph demonstrating hallux valgus and dislocation of lesser metatarsophalangeal joints. B,C: Radiographs taken after MTP fusion and lesser MTP joint forefoot arthroplasty.

|

Metatarsal head excision (Hoffman procedure) has achieved the highest

published success rate—89% good and excellent results (748 of 843

cases) (4,5,9,24,28,33,37,38,43,44,49,66,80,85,91,92,95). I prefer metatarsal head resection to achieve decompression of the MTP joint.

arthroplasty is recurrence of intractable plantar keratoses or recurrent pain due to inadequate resection. Clayton (13,14)

reported a 10% reoperation rate resulting from inadequate resection of

the lesser metatarsal heads. Thus, adequate decompression at the MTP

joint is extremely important to avoid recurrent deformity. While

chronic swelling of the forefoot postoperatively is a frequent

complaint, it usually subsides with time. On the other hand, isolated

resection of one or two metatarsal heads should be avoided, as

intractable plantar keratoses often develop beneath the remaining

metatarsal heads. I believe that revision surgery for the rheumatoid

forefoot becomes necessary most frequently for the following reasons:

(a) irregular lesser metatarsal head resection, (b) limited surgery

with resection of only one or two metatarsal heads, (c) bony regrowth

in the area of the lesser metatarsal head resection, and (d) recurrent

deformity following development of hindfoot or ankle joint problems.

special attention to the resection of the metatarsal heads in a line in

which the first and second metatarsals are of equal length and the

third, fourth, and fifth are progressively shorter, to help avoid

recurrent plantar keratoses. Likewise, meticulous debridement in the

area of the metatarsal head resection is necessary because complete

removal of all bone fragments will minimize bony regrowth. All four

lesser metatarsal heads should be resected: Avoid limited surgery in

which only one or two metatarsal heads are resected. Likewise, in the

presence of hindfoot or ankle joint dysfunction, treat these problems

first. Reserve surgery to correct rheumatoid forefoot deformities for

patients with significant pain and disability, because this is truly a

salvage procedure, and after surgery the lesser toes will have little

active function.

resection arthroplasty for the rheumatoid forefoot frequently fails. McGarvey and Johnson (63)

reported a 67% level of dissatisfaction after Keller arthroplasty

combined with lesser MTP forefoot arthroplasty. They noted recurrent

hallux valgus in 53% and forefoot instability in 27%, and only one

third of their patients reported satisfactory results. They concluded

that first-MTP-joint arthrodesis was preferable to resection

arthroplasty. Later, van der Heijden et al. (91)

reported that 71% of resection arthroplasties of the first MTP joint

were unsatisfactory. Likewise, silastic implant arthroplasty of the

first MTP joint has been recommended as an alternative treatment (23,41).

However, silastic implants have been fraught with both long- and

short-term complications, including implant fracture, synovitis,

recurrent osteolysis, and recurrent pain (81). First-MTP-joint arthrodesis is recommended for the stability that it affords the first ray (17,26,53,57,58,60,67,95).

A resection arthroplasty of the lesser MTP joints affords little

lateral stability to the hallux, allowing lateral displacement. With an

arthrodesis, the first ray bears increased pressure, and a permanently

stable construct is created. Henry and Waugh (36) observed improved weight-bearing function of the great toe following first-MTP arthrodesis, and Watson (95) concluded that arthrodesis was the treatment of choice for correction of a forefoot deformity (Fig. 117.11).

|

|

Figure 117.11. Arthrodesis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. A dorsal incision exposing the MTP joint of the hallux (A). Resection of the MTP articular surfaces (B). A small dorsal compression plate fixing the arthrodesis site (C). AP (D) and lateral (E)

radiographs demonstrating compression-plate fixation of the first MTP joint arthroplasty. The excisional arthroplasty of the lesser MTP joints has been stabilized with K-wires. |

stability of the great toe determine the ultimate level of patient

satisfaction. Fitzgerald (29) noted a high

correlation between degenerative IP joint arthritis and the magnitude

of MTP valgus, and he recommended arthrodesis for 20° of valgus or

more. Recommendations for valgus alignment vary from 15° to 30°, and

whereas a straight position (minimal valgus or slight varus) may lead

to pain along the medial border of the hallux as it strikes the toe

box, excessive valgus is often poorly tolerated as well. I usually

recommend arthrodesis in 15° to 20° of valgus because it tends to

attain a more acceptable first-ray alignment in relationship to the

lesser metatarsals. Recommendations for dorsiflexion (in relationship

to the plantar surface of the foot) vary from 10° to 30°, with 20°

being the average recommendation. Women desiring to wear higher-heeled

shoes may desire increased dorsiflexion. Minimal dorsiflexion (less

than 10°) may leave the patient with a complaint of pressure at the tip

of the toe with ambulation, and dorsiflexion greater than 40° may lead

to increased pressure beneath the first metatarsal head. In measuring

the dorsiflexion at the fusion site, take into account the average

plantar inclination of the first metatarsal, which is 15°. Combined

with dorsiflexion of the phalanx of 5° to 15°, this translates into 20°

to 30° of dorsal angulation at the arthrodesis site.

the toe in neutral rotation when arthrodesed. Excessive pronation may

lead to pressure on the medial border of the toenail, causing an

ingrown toenail.

second is not a contraindication for MTP arthrodesis. Harrison and

Harvey (34) and others (54,58,64,67) have reported significant reduction in the 1–2 intermetatarsal angle following fusion. Mann and Katcherian (58) and Humbert et al. (39)

have noted an average decrease in the 1–2 intermetatarsal angle of

approximately 6° following arthrodesis. Thus, a first metatarsal

osteotomy is rarely indicated after MTP fusion.

-

For an MTP arthrodesis, exsanguinate the foot and use a tourniquet.

-

Center a 5 cm dorsal longitudinal

incision over the first MTP joint and protect the adjacent

neurovascular bundles. They are often ill defined in the presence of

chronic soft-tissue inflammation or where previous surgery has been

performed. -

Deepen the dissection along the medial aspect of the extensor hallucis longus tendon to the MTP joint (Fig. 117.11A). Enhance the exposure with a self-retaining retractor.

-

Release the collateral ligaments and the

adductor hallucis. Release the medial and lateral capsules, and resect

the proliferative synovial tissue. -

Initially, soft-tissue release adequately

decompresses the joint. The amount of bony resection depends on the

shortening achieved with the lateral MTP joint arthroplasties. -

Use transverse osteotomies to resect the articular surfaces of the base of the proximal phalanx and the metatarsal head (Fig. 117.11B).

Make these cuts with a small oscillating saw or osteotome. The first

ray at the conclusion of surgery should not be significantly longer

than the adjacent second ray. Usually, if the lateral forefoot

arthroplasties have been performed before first-ray surgery,

appropriate postoperative length is achieved. Frequently, you must

resect additional bone to shorten the first ray. More bone is usually

removed from the distal metatarsal than from the proximal phalanx. -

Resect the medial eminence of the metatarsal.

-

The angle of the osteotomy of the

articular surface of the proximal phalanx and first metatarsal

determines the position of fusion. Valgus of 10° to 20° and

dorsiflexion of 15° to 25° are most common. Usually, women prefer more

MTP dorsiflexion than men. Determining the valgus position of the

arthrodesis site can be difficult. -

Once the MTP joint has been decompressed,

ascertain the flexibility of the metatarsocuneiform joint by

compressing the transverse metatarsal joint. With adequate flexibility,

fixation in 10° to 20° of valgus is appropriate (Fig. 117.11C, Fig. 117.11D and Fig. 117.11E).An alternative to preparing flat arthrodesis surfaces is

P.3109P.3110

to create curved, cup-shaped surfaces. I have designed cannulated reamers (18,19 and 20)

that prepare the phalangeal and metatarsal surfaces so that rotation,

valgus/varus, and dorsiflexion/plantar flexion can be varied

independently without changing other alignment factors. -

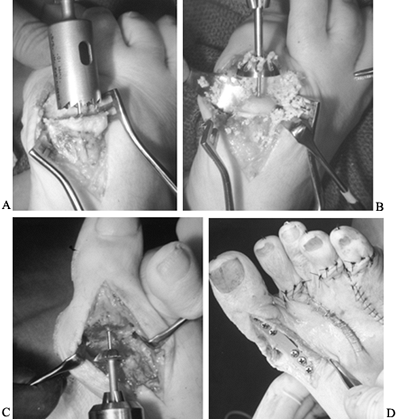

First, employ a barrel-shaped reamer to shape the metatarsal metaphysis into a cylinder (Fig. 117.12A), and then use a cup-shaped reamer to create a convex metatarsal surface (Fig. 117.12B). Ream the base of the phalanx to create a concentric concave surface (Fig. 117.12C).

Figure 117.12. Preparing the metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis site with power reamers. A: Shaping the metatarsal metaphysis into a cylinder. B: Creating a convex metatarsal surface. C: Reaming the base of the phalanx to create a concentric concave surface. D: Stabilizing the first MTP joint with a dorsal Vitallium plate. (From Coughlin M. Arthritis. In: Coughlin M, Mann R, eds. Surgery of the Foot and Ankle, 7th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1999, with permission.)

Figure 117.12. Preparing the metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis site with power reamers. A: Shaping the metatarsal metaphysis into a cylinder. B: Creating a convex metatarsal surface. C: Reaming the base of the phalanx to create a concentric concave surface. D: Stabilizing the first MTP joint with a dorsal Vitallium plate. (From Coughlin M. Arthritis. In: Coughlin M, Mann R, eds. Surgery of the Foot and Ankle, 7th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1999, with permission.) -

Fixation is possible with crossed

K-wires, compression screws, and multiple intramedullary Steinmann

pins. Application of a Vitallium mini-fragment plate dorsally gives

increased strength of fixation (Fig. 117.12D) (21).

In younger patients who do not have significant osteoporosis, fix the

arthrodesis site with a small Vitallium compression plate. Other

methods may be necessary in older patients with osteoporotic bone. -

Once the MTP joint has been placed in the

appropriate amount of valgus and dorsiflexion, stabilize the fusion

site with an 0.062 K-wire. Introduce it from a plantar/medial direction

and drive it proximally across the MTP joint. It may be used

temporarily during the plate application, or it may be left in place

for 3–4 weeks to augment fixation. -

Alternatively, replace the K-wire with a cross-compression screw. In using the dorsal six-hole mini-compression plate (Fig. 117.12D), bend it to 10° to 20° of dorsiflexion and fix it dorsally with six bicortical screws.

-

Take biplanar radiographs to ensure that the IP joint has not been violated.

-

Approximate the wound with interrupted subcutaneous and skin sutures.

and change it weekly. Permit the patient to ambulate in a wooden-soled

postoperative shoe, initially bearing weight on the heel and the outer

aspect of the foot. A below-knee walking cast is an alternative.

Discontinue dressings or casting 8–12 weeks after surgery, when there

is radiographic evidence of successful arthrodesis.

arthroplasty or in the presence of significant osteoporosis,

intramedullary fixation may be necessary to stabilize an arthrodesis

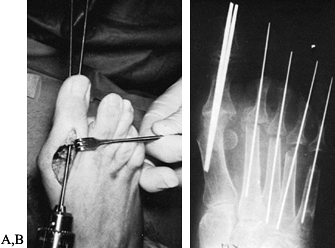

site. Use two double-pointed, threaded 1/8-inch Steinmann pins for fixation (Fig. 117.13).

|

|

Figure 117.13. Intramedullary fixation of first-MTP-joint arthrodesis. A: Introduction of double-pointed threaded Steinmann pins. B: Radiograph showing the pins stabilizing the MTP joint.

|

-

Attach a drill to the distal end of the

pin, and pull this pin, under power, farther distally until its

proximal tip is flush with the prepared phalangeal surface. Use a pin

cutter to remove 4 inches of the distal aspect of the pin so that it

will not interfere when a second pin is drilled distally. -

Center a second double-pointed, threaded

Steinmann pin just to the medial side of the first pin, and drive it in

a similar fashion across the IP joint and out the tip of the toe. -

Attach the drill to the distal end of the

second pin, and pull this pin distally until its proximal point is

flush with the prepared phalangeal surface. -

Position the toe in the desired amount of

rotation, valgus, and dorsiflexion. With axial compression pressure on

the phalanx across the joint, drive the longest pin in a retrograde

fashion across the MTP joint and into the metatarsal shaft. After it

penetrates the proximal metatarsal plantar medial cortex, further

advancement is not necessary. Use a pin cutter to sever the pin,

leaving 1/8 to ¼ inch extending beyond the tip of the toe for ease of removal after successful fusion occurs (Fig. 117.13B). -

Attach the power drill to the first pin that was placed, and drive it proximally in a similar manner.

-

Following placement, cut the pin with 1/8 inch protruding beyond the tip of the toe.

-

Carry out the subcutaneous and skin closures as previously described. Apply a compression dressing.

is solidly healed, remove the pins under a digital nerve block in an

office setting. Oral analgesics are helpful as well. Use a pin remover

or power drill to remove the Steinmann pins.

reported on MTP arthrodesis in 18 feet with an average 4-year

follow-up. Their results were classified as good or excellent in 16 of

18. Seventeen of 18 went on to successful arthrodesis. Degenerative

arthritis of the IP joint was noted radiographically but was not

believed to be clinically significant (Fig. 117.14). A 92% fusion rate (1,074 of 1,164) with the use of conical reamers has been reported (8,19,21,29,40,42,61,64,75,76,82,96,98). Coughlin and Abdo (21)

reported on 47 patients (58 feet) who were evaluated after

first-MTP-joint fusion. Twenty-eight patients had rheumatoid arthritis.

A 98% fusion rate was achieved. The average correction of the 1–2

intermetatarsal angle was to 9.5° and the hallux valgus angle was

corrected to 17.1°.

|

|

Figure 117.14. Degenerative arthritis of the interphalangeal joint associated with first-MTP-joint arthrodesis in minimal valgus.

|

nonunion and malunion. Unsuccessful arthrodesis does not necessarily

lead to a painful pseudoarthrosis, and McKeever (64) noted that a nonunion may still give an acceptable result (Fig. 117.15).

Results tend to vary depending on the method of internal fixation and

operative technique utilized. The highest rate of nonunion (23%) (31)

follows crossed K-wire fixation. Malunion in any plane—whether

rotation, varus/valgus, or dorsiflexion/plantar flexion—is poorly

tolerated. IP joint arthritis may develop following MTP fusion and has

been reported to vary from 6% to 60% (6,12,21,22,36,67,76). Coughlin and Abdo (21) reported a 10% incidence of progressive IP joint arthritis, but only 2% were symptomatic.

|

|

Figure 117.15. Nonunion following arthrodesis. A:

Dislocation of the first and second metatarsophalangeal joints with severe hallux valgus, associated with long-term rheumatoid arthritis. B: Attempted first-MTP-joint arthrodesis. C: Seven years after surgery, the result was successful: painless nonunion with marked improvement in alignment. (From Coughlin M. Arthritis. In: Coughlin M, Mann R, eds. Surgery of the Foot and Ankle, 7th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1999, with permission.) |

degenerative arthritis of the IP joint and bony insufficiency due to

previous excisional arthroplasty or severe osteoporosis. Arthrodesis in

these situations can be more difficult to achieve.

the compliance required for MTP arthrodesis or in the presence of

recurrent infection or atrophic skin, excisional arthroplasty may be a

simple and expeditious procedure. Resection of the base of the proximal

phalanx detaches both the intrinsic muscle insertions and the plantar

aponeurosis. Although this salvage procedure allows correction of the

deformity by decompression of the MTP joint, it shortens the toe and

impairs strength and control of the hallux. Preoperative counseling is

important to ensure that the patient is aware of these factors.

-

Deepen a longitudinal incision on the

dorsomedial aspect of the first MTP joint along the medial aspect of

the extensor hallucis longus tendon. Take care to protect the dorsal

and plantar neurovascular bundles. -

Incise the MTP joint capsule, and expose the base of the proximal phalanx.

-

Elevate the capsule off the medial eminence, and resect the medial eminence.

-

Dislocate the base of the proximal phalanx. With a power saw, resect approximately one third of the proximal

P.3114

phalanx (Fig. 117.16A). Excessive resection may lead to a weakened or flail toe or a cock-up deformity (22). Figure 117.16. An excisional arthroplasty of the hallux (Keller procedure). A: Removal of one third to one half of the proximal phalanx. B: Fixation holes in the base of the proximal phalanx for reattachment of the plantar plate. C: Reattachment of the plantar plate.

Figure 117.16. An excisional arthroplasty of the hallux (Keller procedure). A: Removal of one third to one half of the proximal phalanx. B: Fixation holes in the base of the proximal phalanx for reattachment of the plantar plate. C: Reattachment of the plantar plate. -

I prefer to reattach the plantar plate

and sesamoids to the base of the proximal phalanx. Place the drill

holes 2–3 mm distal to the osteotomized surface (Fig. 117.16B). Reattach the plantar plate to the remaining proximal phalanx with interrupted nonabsorbable sutures (Fig. 117.16C). -

Introduce an 0.062 intramedullary K-wire

at the MTP joint. Drive it distally through the tip of the toe, and

then advance it in a retrograde fashion into the metatarsal head to

stabilize the repair. Bend the pin at the tip of the toe to prevent

proximal migration. -

Reapproximate the capsule and the

subcutaneous tissues with several interrupted absorbable sutures.

Approximate the skin with an interrupted closure.

and change it weekly for approximately 6 weeks. Remove sutures and the

intramedullary K-wire 3 weeks after surgery.

metatarsalgia are major complaints following excisional arthroplasty.

Henry and Waugh (36) reported lateral

metatarsalgia following the Keller procedure and advocated MTP fusion.

You may note a recurrence of hallux valgus after excisional

arthroplasty, especially with progression of the inflammatory process (Fig. 117.17A). A cock-up or claw-toe deformity of the hallux, with detachment of the intrinsic muscle insertion on the base of the

proximal phalanx, has also been reported as a postoperative result of excisional arthroplasty (Fig. 117.17B) (22).

|

|

Figure 117.17. A: A postoperative recurrence of valgus deformity following a Keller procedure in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. B: A cock-up deformity following a Keller procedure.

|

|

|

Figure 117.18. A: Cystic changes of the inferior aspect of the talus associated with hindfoot rheumatoid arthritis. B:

Isolated talonavicular arthritis may be one of the earliest findings with rheumatoid arthritis. (From Coughlin M. Arthritis. In: Coughlin M, Mann R, eds. Surgery of the Foot and Ankle, 7th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1999, with permission.) |

are midfoot and hindfoot pain, swelling, flattening of the longitudinal

arch, and progressive valgus of the hindfoot. Again, conservative care

includes proper footwear, rest to relieve swollen and inflamed joints

from the stresses of weight bearing, padding, and longitudinal arch

supports. When progressive deformity occurs or unrelenting pain is

refractory to conservative treatment, surgery of the hindfoot may be

necessary.

foot. Rheumatoid vasculitis, while uncommon, may present an increased

risk to wound healing. Recognition of the degree of involvement of

other joints necessitates planning various lower-extremity operations.

With isolated forefoot involvement, occasionally a repair of the

rheumatoid forefoot will precede total hip and knee arthroplasty to

improve ambulatory capacity after surgery. Therefore, if the hindfoot

is mobile and relatively uninvolved, forefoot reconstruction usually

proceeds first. When the midfoot and hindfoot are significantly

involved with rheumatoid arthritis, you may delay surgical intervention

so that total knee and total hip arthroplasty may be performed first.

Then align the hindfoot with respect to the overall axial alignment of

the lower extremity. If both forefoot and hindfoot are involved, the

hindfoot reconstruction should precede the forefoot reconstruction.

that are present help in decision making. When an isolated

talonavicular joint is involved (Fig. 117.18B),

arthrodesis of this joint may give good results. Early talonavicular

fusion may arrest the progression of insidious pes planus and eliminate

a later need for more extensive hindfoot correction (27,71). Involvement of the metatarsocunei form joint also may be treated with isolated arthrodesis of the Lisfranc joint.

relatively uninvolved, and when the valgus deformity of the hindfoot

can be passively corrected, subtalar fusion may be indicated. In this

situation, where valgus is usually not excessive, an in situ

fusion with an iliac crest graft can be performed without significant

alteration of the transverse tarsal joint. The development of a valgus

deformity of the hindfoot can occur because of various pathologic

conditions. It may be associated with erosion of the lateral subtalar

joint, hindfoot ligamentous laxity, or both. It may also be associated

with a valgus deformity of the ankle. When a unilateral valgus

deformity occurs suddenly, suspect a rupture of the posterior tibial

tendon. Whether a soft-tissue reconstruction or hindfoot arthrodesis is

preferable depends on the condition of other hindfoot joints and the

severity of the deformity. See Chapter 118 for a

discussion of the treatment of rupture of the posterior tibial tendon, and Chapter 115 for a description of hindfoot arthrodesis.

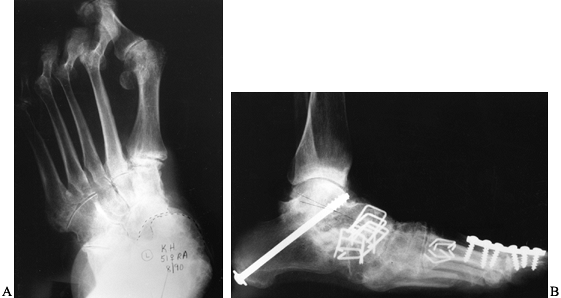

joint or with more severe and irreducible valgus of the hindfoot,

perform a triple arthrodesis, not only to stabilize the hindfoot but

also to correct the deformity (Fig. 117.19). In the patient with hindfoot involvement and a rigid forefoot (Fig. 117.20A), the objective is to obtain a plantigrade foot. Therefore, a triple arthrodesis is usually necessary (Fig. 117.20B) (1).

However, after completion of the subtalar component of this fusion, you

must pronate the forefoot or a plantigrade foot will not be obtained.

This correction is achieved at the transverse tarsal joint.

|

|

Figure 117.19. A,B: Triple arthrodeses performed for rheumatoid arthritis of the hindfoot.

|

|

|

Figure 117.20. A:

Preoperative radiograph demonstrating severe pes planovalgus deformity and forefoot deformity associated with rheumatoid arthritis. B: Radiograph following triple arthrodesis and forefoot arthroplasty with correction of deformity. (From Coughlin M. Arthritis. In: Coughlin M, Mann R, eds. Surgery of the Foot and Ankle, 7th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1999, with permission.) |

forefoot, a subtalar fusion may be feasible, but in all probability a

bone graft to realign the excessive valgus deformity will be necessary.

The objective is to obtain heel valgus of 5° at the completion of the

arthrodesis. Failure to perform a bone graft with a severe valgus

deformity may lead to a recurrence of valgus.

rheumatoid arthritis. When progressive hindfoot valgus has occurred,

hindfoot stabilization is often indicated. The choice between subtalar

and triple arthrodesis depends on several factors, including the

severity of joint involvement, the degree of joint deformity, and the

ankle involvement. Nonetheless, attention to the ankle joint is

necessary, since subtalar or triple arthrodesis with concurrent ankle

disease may eventually progress to a pantalar arthrodesis.

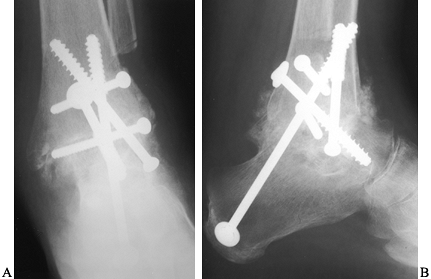

fusion is rarely indicated in rheumatoid arthritis. When significant

degeneration has occurred, surgical intervention may be necessary (Fig. 117.21). Whereas long-term evaluation of total ankle arthroplasty has revealed suboptimal results (47,69,88,99), newer uncemented components have yielded encouraging results (Fig. 117.22) (3,48).

Ankle arthrodesis also may be an alternative for the treatment of

end-stage ankle arthritis refractory to conservative care. On the rare

occasion that subtalar and ankle joints are involved, perform pantalar

arthrodesis. However, even with significant chondrolysis of the ankle

joint, surprisingly good function may be retained.

|

|

Figure 117.21. AP (A) and lateral (B)

radiographs demonstrating ankle arthrodesis in a rheumatoid patient following spontaneous subtalar arthrodesis at an early age. |

|

|

Figure 117.22. Rheumatoid arthritis of the ankle. A: AP radiograph. B: Lateral radiograph. C: Postoperative lateral radiograph after total ankle arthroplasty. D: Lateral radiograph.

|

The use of autogenous iliac crest graft depends on the deformity and

the fusion that is attempted. If correction is desired, bone grafting

may be necessary. Occasionally, a bone mill is used in the preparation

of bone. This graft is then placed in the realigned subtalar joint,

which is then stabilized with internal fixation.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.

A, Waugh W. The Use of Footprints in Assessing the Results of

Operations for Hallux Valgus. A Comparison of Keller Operation and

Arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1975;57:478.

J, Bourbonniere C, Laurin C. Metatarsophalangeal Fusion for Hallux

Valgus: Indications and Effect on the First Metatarsal Ray. Can Med Assoc J 1979;120:937.

M, Peabody T, Gronley J, Perry J. Valgus Deformities of the Feet and

Characteristics of Gait in Patients Who Have Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1991;73:237.

P, Benson G, Sones D. Resection of Proximal Phalanges and Metatarsal

Condyles for Deformities of the Forefoot due to Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin Orthop 1972;82:24.

M, Mann R. Arthrodesis of the First Metatarsophalangeal Joint Utilizing

a Dorsal Plate. Presented at the 7th Annual Summer Meeting of the

American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society, Boston, Mass., July 17,

1991.

S, Johnson K. Keller Arthroplasty in Combination with Resection

Arthroplasty of the Lesser Metatarsophalangeal Joints in Rheumatoid

Arthritis. Foot Ankle 1988;9:75.

C, Johnson K, Donnelly R. Surgical Treatment for Mild Deformities of

the Rheumatoid Forefoot by Partial Phalangectomy and Syndactylization. Foot Ankle 1993;14:325.

Loon P, Ariea R, Karthaus R, Steenaert B. Metatarsal Head Resection in

the Deformed, Symptomatic Rheumatoid Foot. A Comparison of Two Methods.

Acta Orthop Belg 1992;58:11.