Postoperative Treatment Adjuncts

postsurgical stiffness, continuous passive motion (CPM) is useful in

maintaining motion and preventing stiffness.

bleeding and edema occurring within minutes after surgery or trauma,

and since motion has been shown to negate these changes (4,9), this treatment should commence as soon as possible following surgery, ideally in the recovery room (2,4). However, this is not always practical.

motion obtained at the time of surgery following intraarticular

fracture fixation, contracture release, synovectomy, and excision of

heterotopic ossification. It may also be useful following the

replacement of arthritic joints that were stiff preoperatively or in

any setting in which swelling and motion restriction are anticipated.

presence of ligamentous insufficiency if the elbow is unstable or if

fracture fixation is not rigid or is tenuous. The most common

contraindication is poor-quality soft tissue and concern about wound

dehiscence.

-

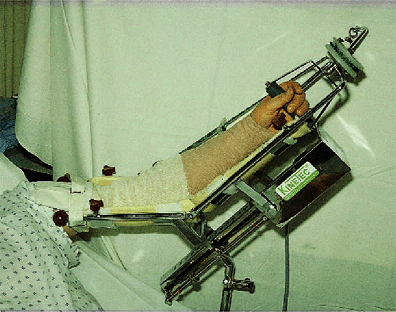

Access to an effectively designed device for inpatient and outpatient use (Figs. 9-1 and 9-2).

Figure 9-1. Bedside-based CPM machine.

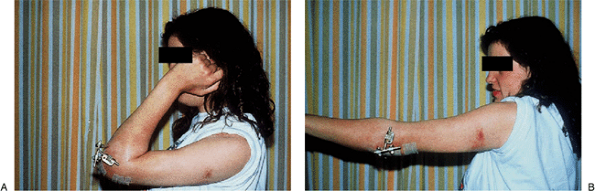

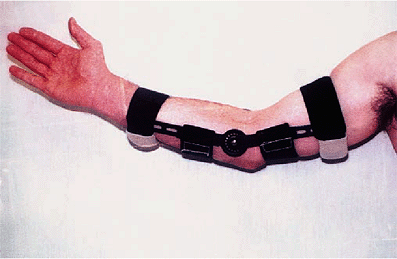

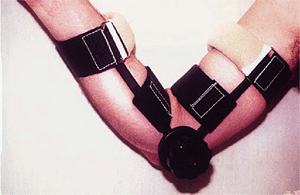

Figure 9-1. Bedside-based CPM machine.![]() Figure 9-2. A,B: Portable CPM unit.

Figure 9-2. A,B: Portable CPM unit. -

A nursing staff knowledgeable in the applications of CPM.

-

A compliant patient.

-

Physician understanding and commitment and communication with patient and nursing staff.

-

Until motion is started, it is preferable

to elevate the limb with the elbow in full extension and wrapped in a

compressive Jones dressing to minimize swelling. -

A drain is usually useful to prevent periarticular accumulation of blood.

-

Before starting CPM, all circumferential

wrapping (Jones, cling, etc.) should be removed and replaced with a

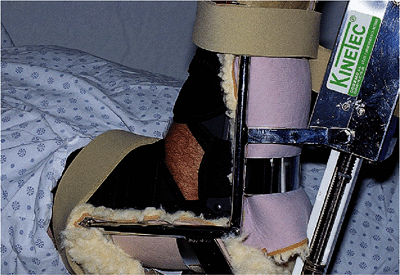

single elastic sleeve. Figure 9-3. Proper position with elbow and device flexion axis coincident. In this instance the elbow is also protected in a brace.

Figure 9-3. Proper position with elbow and device flexion axis coincident. In this instance the elbow is also protected in a brace. -

The arm is carefully positioned in the

CPM device and the elbow flexion axis, or brace hinge aligned with the

flexion axis of the device (Fig. 9-3). -

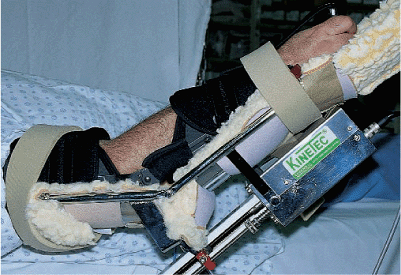

The hand and forearm are secured with well-padded supports (Fig. 9-4), especially if a brachial plexus block is being used.

-

The wound is examined to ensure that its integrity is not compromised during elbow flexion.

|

|

Figure 9-4. The hand and forearm are secured and carefully padded if sensory changes exist due to the brachial plexus block.

|

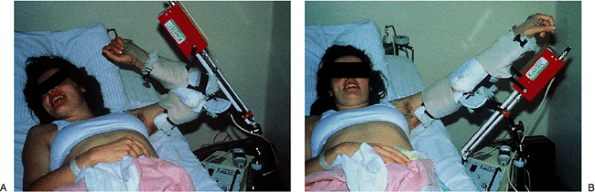

postoperative period. Once CPM is started, it is necessary that the

full range of motion be utilized (Fig. 9-5).

The tissues are being “squeezed” alternately in flexion and extension,

as CPM causes a sinusoidal oscillation in intraarticular pressure. This

not only rids the joint and tissue of excess blood and fluid, but

prevents further edema from accumulating (4).

In the first 24 hours, swelling can develop in minutes (as a result of

bleeding), so CPM should be applied early and be continuous. Only

bathroom privileges are allowed.

requires close supervision by someone skilled with its use, so it is

mandatory that the patient and family be involved and educated from the

beginning regarding the principles of use and how to monitor the limb.

Frequent checking and slight adjustments of position prevent

pressure-related problems. The arm tends to slip out of the machine, so

it must frequently be readjusted. If the full flexion arc cannot be

immediately attained, the physician must increase the adjustments as

rapidly as tolerated by the soft tissue.

amount of time required for swelling to develop increases also, so that

longer periods out of the machine are permitted.

CPM treatment at home should be used long enough to get the patient

through the period during which he or she will be unable to accomplish

the full range of motion independent of assistance. This can be several

days to several weeks, usually a month.

This permits a range from analgesia to anesthesia by varying the dose

of bupivocaine, a long-acting local anesthetic. In many cases, the dose

employed initially is sufficient to cause a complete or nearly complete

motor and sensory block. Motor blockade requires splinting of the wrist

to protect it. Moderate or complete anesthesia, as opposed to analgesia

with minimal anesthesia, requires careful attention to the status of

the limb overall, as the patient’s protective pain response is no

longer present and impending complications such as compartment syndrome

can be missed.

hospital, then removed. At that time the patient is generally able to

maintain the same range of motion with oral analgesics. The

goal is to have the patient leave the hospital capable of moving the elbow from about 10 to 135 degrees of motion actively.

|

|

Figure 9-5. A,B: The range of motion on CPM should be full. This permits the tissues to be squeezed alternately in flexion and extension.

|

|

|

Figure 9-6. A,B:

Typical range of motion seen at 3 weeks following a distraction interposition arthroplasty treated postoperatively using continuous passive motion. |

has also been used effectively if a brachial plexus block is

contraindicated, unsuccessful, or unavailable.

require a transfusion. Excessive wound or incision pressure at full

flexion is the greatest concern. The incision must be visible to the

surgeon in the early stages of CPM treatment. If wound compromise

occurs, CPM is discontinued. Excessive pressure from an improperly

applied or padded device is particularly possible in limbs rendered

arthritic by the brachial block. Hematomas are drained surgically.

basis for its utility, there is little clinical evidence that clearly

documents its effectiveness compared with a control population (3). Nonetheless, it is the authors’ opinion, shared by others, that this is a valuable modality in selected patients (1) (Fig. 9-6).

arthritic conditions is stiffness. The accepted principle to avoid this

after a fracture is rigid fixation. Early motion has also been used to

decrease this sequelae after fractures and injury at the elbow (see the

preceding section, “Continuous Passive Motion”). In spite of these

measures, because of limitations imposed by the injury or in executing

the ideal treatment, and due to the inherent biology and response to

injury, stiffness of the elbow is a common problem (7).

Unfortunately, aggressive physical therapy to address posttraumatic

stiffness is not always successful and, in fact, may contribute to

making the contracture worse.

response to insult. The goal of splint treatment is to stretch the soft

tissues, thus maintaining the length of the capsule and ligaments.

The

question then arises as to the best method of providing a force to

stretch the periarticular soft tissues: dynamic or static adjustable

splinting. The selection of one program over the other is dependent on

one’s philosophy and interpretation of the concepts and goals of splint

usage (8,9,10).

|

|

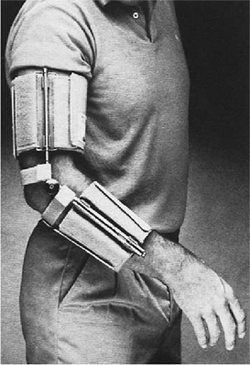

Figure 9-7. Commercially available dynamic splint. The tension and excursion may be adjusted by the patient.

|

treating impending or developing stiffness, probably because dynamic

splints are readily available (Fig. 9-7). The

rationale of dynamic splinting is based on considering the elbow

capsule as a viscoelastic tissue. The response of such a tissue to a

constant force is shown in Fig. 9-8. The response in

the soft tissue to a persistent force is a deformation, which is called creep (10).

However, the constant force may cause irritation of the soft tissue;

hence inflammation is commonly associated with dynamic splinting.

Nonetheless this type splinting remains a commonly employed option for

many (8).

|

|

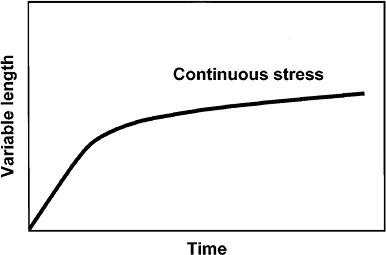

Figure 9-9. Tissue response to a single discrete force results in stress relaxation of the viscoelastic tissue over time.

|

|

|

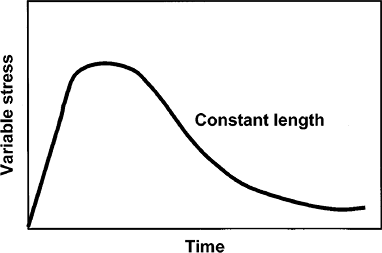

Figure 9-8.

Viscoelastic tissue response to a constant force resulting in gradual stretching of the tissue. However, the potential for inflammation is not demonstrated by this curve but is possible if the force is constantly present, which is the case in dynamic loading. |

applied to the elbow, which results in a discrete stress being imparted

to the tissue. However, since the splint position is not further

altered, the soft tissue is allowed to undergo a process called stress

relaxation that occurs over a period of time in response to the fixed

position (Fig. 9-9). It is felt that stress

relaxation lessens the likelihood of tissue irritation and of

inflammation. Thus the elbow is more amenable to this type of load

application and splint philosophy, since it is inflammation that breeds

additional swelling and scarring.

of a flexion or extension contracture that is amenable to stretch

deformation. Experimental data (6) and clinical experience suggest tissue is amenable to this type of therapy in three stages as follows (9):

I, onset to 3 months from injury, highly effective; II, 3 to 6 months,

moderately successful; III, 6 to 12 months, variably effective. A

stable articulation and articular surface is a prerequisite for splint

therapy to be effective in any of these stages.

not tolerate the constant forces from the splint. Excessive or

increasing swelling can also cause the development of neural symptoms

that require splint discontinuance or program alteration as follows:

sensory—alter the pressure points; motor—alter basic program or

discontinue.

With traditional humeral-based support, the soft tissue tends to “bunch

up” in the brace in flexion, and this tendency limits further flexion.

The hyperflexion brace is stabilized at the shoulder, and the elbow is

flexed through a mechanism applied to the wrist with an adjustable

strap.

|

|

Figure 9-10. A static adjustable splint currently used by the author in which the force is directly applied to the axis of rotation.

|

|

|

Figure 9-11. The same splint shown in Fig. 9-10 but reversed and being used in the flexion mode. Hence the splint is called the universal splint in our practice.

|

|

|

Figure 9-12.

To avoid soft-tissue impingement associated with straps supporting braces about the elbow, a hyperflexion splint that frees the elbow of any encumbrance is based at the shoulder and flexion across the elbow by way of the wrist. |

the elbow flexion axis. The brace should have broad surfaces for force

application at the wrist and forearm, and the support at the brachium

should not cause soft-tissue constriction. The precise use is described

later in a format designed to be individualized and given to the

patient.

static adjustable splint may be modified, depending on individual needs

and progress.

-

General goals.

To attain improved motion of the elbow, inflammation must be avoided.

This is done with the use of the anti-inflammatory agents, heat and ice

and education of the patient to the signs of inflammation. -

Cardinal signs of inflammation.

Increased soreness, increased discomfort with use, swelling or,

commonly, a progressive loss of motion rather than improvement from day

to day. -

Treatment of inflammation.

Avoid the causative factor. Be less vigorous with static adjustable

splint, adhere to the heat/ice program, and take antiinflammatory

agents as prescribed. If it seems inadequate, the program may need to

be modified. Check with your doctor. -

Direction of improvement.

Often both increased elbow flexion and extension are being sought. In

general, the motion which is needed most is addressed at night as well

as during the day. The opposite motion is encouraged during the day. -

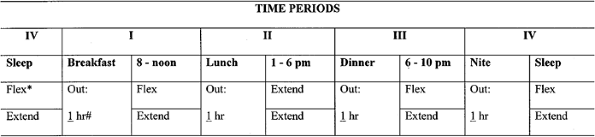

Typical splint program (20-hour program, 0 to 3 weeks from injury or surgery) (Fig. 9-13).

-

Morning. Upon

rising in the morning the splint is removed. Gently flex and extend the

elbow while taking a hot bath or shower for approximately 15 minutes.

Take antiinflammatory agent. -

Apply the splint in the opposite

direction as that which was used at night. Apply it to the point where

it is recognized that the elbow is being stressed but pain is not

extreme or intolerable. -

Noon. The

splint may be removed for 1 hour in the morning, 1 hour in the

afternoon, and 1 hour in the evening. Reapply the splint in the

opposite direction after these rest periods. Figure 9-13.

Figure 9-13.

Flexion and extention visual splint (20 hours and 3 weeks). The hours

are changed for the Phase II/6 hour program. *Circle direction of

splinting: extension or flexion; write in duration out of splint. A

sample of the “20-hour” daily program given to the patient at the time

of splint prescription. A visual prescription of the splint usage

program is provided to those undergoing splint therapy. -

Evening. Use

the elbow when out of the splint as able during these periods and in

the evening. While out of the splint if the elbow is sore or seems

inflamed, apply ice for 15 minutes before bedtime. If not inflamed but

stiff, apply heat for 15 minutes, gently working the joint in flexion

and extension. -

Night. Before

going to bed at night apply the splint in the direction needed most.

Application should be sufficient to be aware that the elbow is being

stressed and a person should be able to sleep comfortably for about 6

hours without being awakened by elbow pain.

P.169 -

that disappears when the splint is removed, it is acceptable to

continue the program but to alter it to minimize nerve symptoms. If the

numbness does not resolve or motor symptoms develop, discontinue the

splint and call your doctor.

-

Sleep in direction needed most.

-

In the morning, do a 15-minute warm-up.

Take antiinflammatory; use extremity as tolerated for 2 hours. Then

apply splint in opposite direction to that used during sleep. -

At noon, remove the splint for 2 hours. Reapply same splint used at night.

-

At dinnertime, remove the splint for 2 hours. Reapply in the evening in opposite direction to that used at night.

-

At night, apply ice if sore and inflamed.

Apply heat if stiff. Remove splint 1 hour before bedtime, then apply it

in the direction in which motion is needed most. -

Reassess after 3 weeks. Alter the program further as needed.

approximately 360 braces for patients with various expressions of stiff

elbow. We estimate an overall success rate of the

splinting

program as about 80%. That is, the splint was considered a beneficial

adjunct. It is not a panacea. It is this experience that has resulted

in the program that is currently employed. These splints are now

commercially available (Prosthetic Laboratories of Rochester, Inc.; 201

1st Ave. S.W.; Rochester, MN 55902). This experience has also led to

the further development of effective splints by Air Cast and other

commercial vendors.

explaining the rationale of brace management and specifically

discussing the program based on the specific goals of treatment.

SW, Kumar A, Salter RB. The effect of continuous passive motion on the

clearance of a hemarthrosis from a synovial joint: an experimental

investigation in the rabbit. Clin Orthop 1983;176:305–311.

LJ, Lennon R, Adams R, et al. The technique and efficacy of axillary

catheter analgesia as an adjunct to distraction elbow arthroplasty: a

prospective study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1993;2:182–189.

RE, Russell PS. Studies on wound healing, with special reference to the

phenomenon of contracture in experimental wounds in rabbits’ skin. Ann Surg 1956;144:961–981.