Nonacute Elbow, Wrist, and Hand Conditions

-

History. As

with any medical problem, the history of events leading up to the

patient’s visit to the physician with an upper extremity problem is

critical. The history should contain family history, social history,

personal medical history unrelated to the musculoskeletal system,

infectious disease history, and risk behavior history. Some additional

key facts to record include the following:-

Handedness. Is the patient right- or left-handed?

-

Work-relatedness.

If the patient believes a problem is related to work or a series of

events, it is the physician’s job to document the patient’s beliefs.

The physician can do this by “quoting” the patient exactly. It is not the physician’s job or duty to question the veracity of a patient’s complaint. -

Mechanism of onset.

Record the details of the incident or accident as completely as

possible. This is particularly relevant for motor vehicle accidents.

Record details such as whether the patient was in the car, whether the

air bags were deployed, whether the steering wheel was bent

(particularly if the injured person was the driver), and the amount of

damage done to the car. -

Date of most recent tetanus booster. This is important with any direct trauma. Do not assume that another first examiner has resolved this issue.

-

-

Physical examination

-

General. At first glance, the upper extremity is a mirror of the lower. But, several key differences are obvious:

-

The shoulder has more freedom of motion and is consequently less stable than the hip.

-

The “patella” of the elbow is fused to the ulna as the olecranon.

However, it performs a similar function to the patella in that it

increases the “lever arm” for the attached muscle (triceps in the arm,

quadriceps in the leg). -

The elbow and wrist

participate equally in guiding forearm rotation (supination and

pronation). A similar motion is not available in the lower extremity. -

The wrist has more motion and less bony stability than the ankle.

-

The fingers are longer in proportion to the palm than the toes in relationship to the midfoot.

-

The thumb is longer and is opposable to the digits.

-

-

Region specifics

-

Elbow

-

The elbow joint moves in a hinge manner

at its articulation between the humerus and ulna. Thus, the

ulnar-humeral articulation is uniaxial. In addition to its critical

role in forearm rotation, the radius can transmit load to the humerus

in “high-strength” situations. This issue is even more important if the

elbow ligaments are injured. In general, the elbow gains minimal

stability from muscle support and is reliant upon ligament support to

guide joint motion. -

Examination of this joint should document

the active and passive arc of flexion and extension. Varus (lateral

ligament loading) and valgus (medial ligament loading) should be

assessed. -

Standard radiographs include anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views.

-

-

Forearm

-

Rotation of the forearm is guided by bone

support at the proximal and distal radioulnar joints (PRUJ and DRUJ,

respectively). Additional stability and guidance for this motion is

provided by the interosseous membrane. -

Examination should record the active and

passive arc of supination and pronation. Crepitance or pain at the PRUJ

or DRUJ should be noted. Pain or swelling in the mid-forearm should be

assessed. -

Standard radiographs include AP and lateral views.

-

-

Wrist

-

The wrist moves in a multiaxial manner.

The carpus is divided into a proximal (scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum)

and distal (hamate, capitate, trapezoid, trapezium) row. Some of the

key intercarpal articulations have more easily described relationships

(the scaphoid moves relative to the lunate in flexion and extension).

However, taken as a whole, the wrist is multiaxial and its motion is

highly dependent on ligament function. There is no direct attachment of

an extrinsic (forearm based) muscle or tendon to the bones of the

proximal wrist. Thus, these bones (scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum)

are 100% dependent on ligament integrity for function. -

Examination

should record passive and active arcs of flexion, extension, radial

deviation, and ulnar deviation. Obvious pain or crepitance should be

recorded as specifically as possible. -

Standard radiographs

include posteroanterior (PA) or AP and lateral views. If the scaphoid

is the focus of attention, AP and lateral views of the scaphoid should

be specifically requested. These are oblique to the normal PA and

lateral views of the wrist.

-

-

Hand

-

The hand

contains uniaxial (interphalangeal), multiaxial-stabilized (metacarpal

phalangeal), and multiaxial-unstabilized (first and fifth

carpometacarpal) articulations. Thus, these joints have varying degrees

of ligamentous or muscle stability requirements. For example, the

proximal interphalangeal joint of the index finger is dependent on

ligament support. Whereas, the index finger’s metacarpophalangeal joint

can be partially stabilized by hand intrinsic muscle support. -

Examination

should record active and passive arcs of flexion and extension for all

joints. Thumb examination should additionally include ability to abduct

(palmar and radial), adduct, retropulse (extend), and oppose. Joint

stability should be tested and any masses or tenderness noted. -

Standard radiographs

include PA and lateral views. Note: To obtain a lateral view of a

finger, the adjacent digits need to be moved aside. Similar to the

scaphoid, “normal” thumb views are oblique to the hand. -

Note: Always examine the opposite or unaffected side. This is particularly important when assessing stability.

-

P.284 -

-

-

Developmental birth conditions

-

Radial agenesis.

Absence of the radius can be full or complete. Occasionally, this

longitudinal deficiency is accompanied by thumb agenesis. An even more

rare condition is presence of the radius and absence of the ulna. In

either event, stability of the wrist is compromised. The deformity is

often characterized with a “club hand.” The absence of the radius would

then be termed a radial club hand. Full assessment of this condition

requires complete assessment of the child to include renal,

cardiovascular, neural, and other musculoskeletal regions (shoulder,

elbow, and hand). If the child has associated anomalies, correction of

the deformity at the forearm carpal articulation may actually

compromise function. Thus, any direct treatment must consider the whole

forearm and carpal articulation. -

Syndactyly

-

This is the most common congenital hand condition (1 in 2,000 live births). The cause is not known. It is divided into simple (soft-tissue joining of two or more digits with no associated bone or joint anomaly) and complex

(joining of two or more digits to include soft tissue and bones or

joints) categories. Further subdivision is possible based on the length

of the syndactyly. Complete syndactyly involves the whole length of the finger, whereas incomplete

syndactyly does not. Simple syndactyly differences are often completely

correctable. The complex differences, however, can occur in combination

with other congenital differences (Apert syndrome). -

In general, surgical correction of this

difference should be performed as soon as is anesthetically feasible.

Correction of a multiple finger difference is done in stages.

Limitations of correction are often related to digital blood supply;

usually, full-thickness skin grafts are required at surgery.

-

-

Polydactyly

-

This difference is classified into preaxial duplication

(involvement of the thumb), central duplication (index, middle, or ring

involvement), and postaxial duplication (small finger involvement). Postaxial duplication

has a clear genetic component and is seen in as many as 1 in 300 live

births. Correction of this difference usually involves excision. The

degree of duplication and joint involvement determines the complexity

of the procedure. -

Treatment methods

for thumb duplication generally focus on excision of an unstable

duplicate thumb. Duplication of the thumb has been characterized to

occur in at least seven different patterns. The outcome of thumb

reconstruction depends on the ability to create a thumb of appropriate

length, rotation, stability, and mobility and to integrate the thumb

into the child’s daily routine. It is on this basis that earlier

correction is generally recommended.

-

-

Madelung’s deformity.

First described by Malgaigne in 1855 and later by Madelung in 1878,

this difference of growth related to the distal epiphysis of the radius

is believed to be congenital in nature, although it is usually not

noted before adolescence. It is a rare, genetic condition transmitted

in an autosomal dominant pattern. Because of incomplete growth of the

radius, the clinical presentation may be prominence of the ulnar head

(distal ulna). Alternatively, abnormal forearm rotation may be the

presenting complaint. At present, pain may not be a component. The

method of surgical correction (shortening of the ulna versus

lengthening of the radius) is less important than the goal of obtaining

and preserving stable, painless forearm rotation with full and

unrestricted use of the wrist. -

Brachial plexus

-

The brachial plexus comprises a

coalescence of cervical and upper thoracic spine nerve roots. It

traverses the space between neural foramina and the infraclavicular

region where it again separates into individual nerves. Birth injuries

relating to the brachial plexus are thought to represent an avulsion or

stretch of the upper (Erb’s), lower (Klumpke’s),

or both aspects (combined) of the brachial plexus. These injuries occur

generally in the process of vaginal delivery of the child. -

Critical to the examination

of any child with a presumed brachial plexus lesion is verification of

normal shoulder bony anatomy. The physician should document this by way

of physical examination and shoulder radiographs confirming the

shoulder (glenohumeral joint) is located. -

Occasionally a child with nothing more than a fractured clavicle (birth related)

will be mistaken to have a brachial plexus injury. Thus, it is

important to include the clavicle in the physical examination of the

infant. Generally speaking, a single AP chest radiograph suffices to

detect such a fracture in the neonate. -

Management of brachial plexus injuries at birth should include the following:

-

Documentation of glenohumeral joint status (located)

-

Documentation of passive mobility of all upper extremity joints, including cervical spine mobility

-

Documentation of observed active motion in shoulder, upper arm, elbow, forearm, wrist, and hand

-

Initiation of twice-daily active-assisted “whole-arm” mobilization program to be completed by the care team or parents

-

Plan for follow-up examination on a

frequent interval to verify understanding and completion of passive and

active-assisted exercises and available joint motion (both passive and

active—looking for change or improvement)

-

-

The prognosis

for many brachial plexus injuries is for complete or near complete

recovery. Children whose function remains compromised are evaluated and

occasionally operated upon within the first 6 to 18 months of age. The

treating physician who cannot document substantial improvement early

(less than 6 months of age) should arrange further evaluation by an

upper extremity specialist.

P.286 -

P.285 -

-

Delayed presentation of developmental differences

-

Cerebral palsy

-

Patients with cerebral palsy constitute

the largest group of pediatric patients with neuromuscular disorders.

The frequency varies from 0.6 to 5.9 patients per 1,000 live births.

Difficulties related to this problem persist into adulthood. However,

unlike many neuromuscular disorders, this condition does not progress.

Relative progression of the disorder may occur in relation to growth,

weight gain, or onset of degenerative change. However, any real

progression should cause review of the original diagnosis. Generally,

the problem relates to prenatal, natal, or early postnatal brain

injury. The injury can express itself in a wide pattern, ranging from

single limb to whole body involvement. Two clinical types of injury are

seen:-

Spastic type—represents an injury to pyramidal tracts in the brain. Exaggerated muscle stretch reflex and increased tone are seen.

-

Athetoid type—probably a lesion in the basal ganglia. Continuous motion of the affected part is present; this type is more rare.

-

-

Diagnosis is

the first component of treatment. In cases with lesser involvement,

diagnosis may not be obvious until the child fails to reach normal

motor milestones or has difficulty with coordinated tasks. In some

cases, the diagnosis is suspected because of early “under-use” of a

part. For example, a child does not have a strong hand preference

before 18 months of age. -

Treatment of

cerebral palsy should always focus on functional improvement. Surgery

generally has a cosmetic benefit, but the initial goal should be to

improve a specific function. Intelligence and sensory awareness of the

child are the two biggest determinants for functional improvement after

surgery. Improvements of arm function are possible by improvement in

the position of the shoulder, elbow, forearm, wrist, hand, and thumb.

Three of the more successful surgeries are release of an internal

rotation/adduction spastic contracture involving the shoulder,

release/rebalancing of a flexed and pronated spastic wrist/forearm, and

release/rebalancing of a thumb into palm deformity.

-

-

-

Nerve. Nerve

tissue is responsible for communication in two directions between the

brain and the external environment (peripheral). Like the brain, nerve

function is highly dependent on oxygen. Although depolarization of a

single axon is energy independent, repolarization of the axon is

dependent on adenosine triphosphate to run the Na+/K+ pump to “recharge” the axon potential. Thus, although local loss of O2 will not cause death of the peripheral axon cell body, local loss of O2 will affect the ability of the axon to conduct information. This change in conduction is generally transient, depending on O2 availability. However, frequent episodes of

P.287

reduced O2

can produce permanent change in function. Common sites for nerve

dysfunction to occur in the arm are the carpal canal (median nerve),

the cubital tunnel (ulnar nerve), and the arcade of Froshe (posterior

interosseous branch of the radial nerve).-

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS)

-

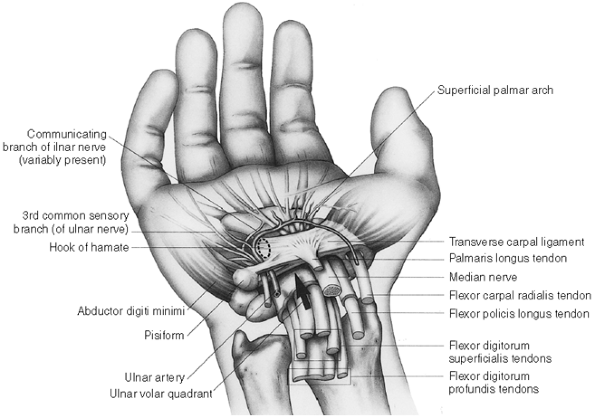

Fig. 20-1

depicts the carpal tunnel as seen from end on. The carpal tunnel is

seen to be formed by the three bony borders of the carpus (trapezium,

lunate, hook of hamate) and the transverse carpal ligament. As such, it

is a defined space with a fixed volume. Changes in the fixed volume can

occur as a result of actual changes in the bony outline resulting from

late effects of trauma or arthritis. Also, relative change in volume

available can be the result of mass effect occurring from tendon or

muscle swelling or synovitis, presence of an anomalous muscle, or

presence of an actual mass (e.g., lipoma). The patient with reduction

in available volume is less able to tolerate or accommodate increases

in pressure within the carpal canal. Thus, in patients with reduced

carpal canal volume, provocative maneuvers such as Tinel’s (tapping or

percussion of a nerve in a specific location), Phalen’s (flexion of the

wrist causing indirect nerve pressurization), or Durkin’s compression

test (manual pressure by examiner upon the median nerve) are more

likely to be positive. -

Presenting complaint is most commonly pain in the median nerve distribution. Pain is often exacerbated at night or by specific activities (1).

As the syndrome advances, numbness occurs in the distribution of the

median nerve. Weakness of the thenar muscles with associated wasting is

a late stage event. -

Laboratory testing.

Radiographs to check for degenerative joint disease (DJD) or old

fractures are occasionally of benefit. The most widely accepted

diagnostic method is electrodiagnostic testing [electromyogram/nerve

conduction velocity (EMG/NCV)]. This test can document slowing of nerve

P.288

conduction

and early muscle denervation. The EMG is most specific if the symptoms

have been present for at least 1 month. Given the association of

hypothyroidism and rheumatologic discorders, testing of the thyroid

stimulating hormone (TSH) and rheumatoid factor (RF) should be strongly

considered. Finally, carpal tunnel syndrome is very common in

pregnancy, and symptoms frequently resolve after delivery. Figure 20-1.

Figure 20-1.

The carpal tunnel is bounded by bone on three sides and by the ligament

(transverse carpal) on one side. Guyon’s canal overlies the ulnar side

of the carpal tunnel. The median nerve lies in the radial volar

quadrant of the carpal canal. Generally, it is immediately below or

slightly radial to the palmaris longus. -

Treatment of

CTS focuses on relief of pain. Initial therapy can include medication

to relieve pain and swelling [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

(NSAIDs)], splint support, and exercises to increase mobility. No test

or study has shown definite value for NSAIDs in management of CTS,

except as they are related to relief of pain. An injection of

corticosteroid into the carpal tunnel may be effective. There is some

benefit from vitamin B6 and C oral therapy. -

Surgery for

relief of CTS symptoms is generally successful, with patient

satisfaction exceeding 95% and complications less than 1%. The surgery

can be completed by a variety of methods (open surgery versus

percutaneous or arthroscopic-assisted release) without a clear benefit

to one method versus another, as long as complete longitudinal division

of the transverse carpal ligament is achieved along the ulnar half (1,2,3,4). Return to unrestricted activity after CTS surgery requires 4 to 8 weeks.

-

-

Cubital tunnel syndrome

-

The cubital tunnel

is formed by the bony borders of the medial epicondyle and medial ulna

and overlying soft-tissue constraints including the entrance between

the ulnar and humeral head of the bipennate flexor carpi ulnaris. It is

a defined space with a fixed volume. Changes in the fixed volume can

occur as a result of actual changes in the bony outline as a result of

late effects of trauma or arthritis (osteoarthritis or rheumatoid

arthritis). Relative change in volume available can be the result of

mass effect occurring from tendon and muscle swelling or synovitis.

Laxity of the soft-tissue–supporting structures can allow the ulnar

nerve to migrate out of the cubital tunnel and over the medial

epicondyle during flexion. This motion is often referred to as

subluxation of the ulnar nerve and produces a “Tinel-like” distal

sensory disturbance. -

Presenting complaint is most commonly pain in the distribution of the ulnar nerve distribution (5).

Pain is often exacerbated at night or by specific activities. As the

syndrome advances, numbness occurs in the distribution nerve. Weakness

or atrophy of the hypothenar muscles is a late stage event. -

Laboratory testing

(thyroid function tests and rheumatoid factor) and radiographs (DJD,

old fractures) are occasionally of benefit. The most widely accepted

diagnostic test method is electrodiagnostic testing (EMG/NCV). This

test can document slowing of nerve conduction and early muscle

denervation. Again, the EMG is most sensitive if symptoms have been

present for at least 1 month. -

Treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome focuses on relief of pain (6).

Initial therapy can include medication (NSAIDs) to relieve pain and

swelling, provision of antielbow flexion splint support or pad, and

exercises to increase mobility. No test or study has shown definite

value for NSAIDs in management of cubital tunnel syndrome, except as

related to relief of pain. -

Surgery for

relief of cubital tunnel symptoms is substantially less successful than

surgery for relief of CTS. The surgery can be completed by a variety of

methods (small versus large surgical exposure) without a clear benefit

to one method versus another as long as the point of observed nerve

compression is released (7). The patient returns to unrestricted activity 12 to 24 weeks after surgery.

-

-

PIN compression/other

-

The PIN (posterior interosseous) branch of the radial nerve travels through a defined space with a fixed volume. The tightest region of this

P.289

space is formed by a fascial connection at the proximal margin of the

two heads of the supinator muscle in the proximal forearm (arcade of

Froshe). Changes in the fixed volume can occur as a result of actual

changes in the bony outline that result from late effects of trauma or

arthritis. Relative change in volume available can be the result of

mass effect occurring from tendon and muscle swelling or synovitis,

presence of an anomalous muscle, or presence of an actual mass (e.g.,

lipoma). The most common cause of nerve irritation in this region is

believed to be the result of thickening of the facial margin in

response to time (age) and stress. -

Presenting complaint

is most commonly pain in the general region of the supinator muscle.

Pain is often exacerbated at night or by specific activities. As the

syndrome advances, numbness does not occur. Weakness of the PIN

innervated muscles with associated wasting is a late stage event. -

The most widely accepted diagnostic test

method is electrodiagnostic testing (EMG/NCV). PIN compression with

this test is of substantially less benefit when compared with other

nerve compression syndromes. Nonetheless, it shows muscle denervation

in some cases. -

Treatment of

PIN syndrome focuses on relief of pain. Initial therapy can include

medication to relieve pain or swelling (NSAIDs) and exercises to

increase mobility. Splints may exacerbate the problem if placed over

the nerve. Wrist splints to reduce load on wrist extensors (the wrist

extensors cross over the supinator) are occasionally helpful. As with

the other nerve compression syndromes, no test or study has shown

definite value for NSAIDs in management of PIN syndrome. -

Surgery for

relief of PIN symptoms is substantially less successful than surgery

for relief of CTS. A variety of surgical approaches have been

described. The arcade of Froshe is identified and released. Return to

unrestricted activity after surgery requires 12 to 24 weeks.

-

-

Other. Nerve

compression can essentially occur wherever a nerve exits or enters a

fascial plane/transition zone. The foregoing are the most common sites.

Knowledge of extremity anatomy will aid the student in assessing other

sites of suspected nerve entrapment.

-

-

Muscle and tendon.

Muscles and tendons work together to generate and transmit force. The

effect of load transfer depends on stable points of origin and

insertion. Thus, at least three locations of function failure are apparent: (1) bone–muscle origin, (8) muscle–tendon junction, and (9) tendon–bone insertion. An example of each is provided.-

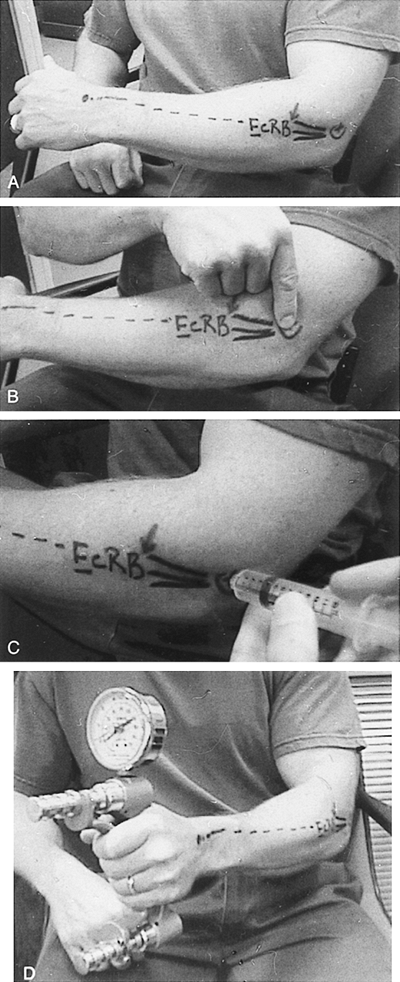

Bone–muscle origin interface failure: lateral epicondylitis (Fig. 20-2)

-

Failure of the muscle origin

of forearm extensors (lateral) or flexors (medial) is a common

condition. The condition is uncommon in youths or persons of advanced

age. It is occasionally seen in conjunction with working activities.

Most often, the condition begins after a period of repetitive stress. -

Presenting complaint

is usually pain focused at the muscle origin. Resisted use of the

muscle aggravates the condition. The pain usually subsides with rest.

Swelling is rarely present; no mass is seen with this condition. Range

of motion may be uncomfortable; but a full active or active-assisted

range of motion should be possible. -

Laboratory testing

is of no particular value. Screening roentgenograms may be obtained but

are generally normal for age. An injection test may be of confirmatory

benefit (9). This is performed as outlined in Fig. 20-2.

In this situation, the hope is that a precise injection of lidocaine

with steroid into the area of extensor origin will eliminate or

significantly alleviate the pain. -

Treatment of

epicondylitis focuses on reducing the stress at the “inflamed”

interface. Theoretically, if the stress is low enough, the healing

process can succeed in healing the injured interface. Thus, use of

splints (Froimson barrel or forearm band) to reduce the load on the

injured muscle origin, massage to increase the blood supply for

healing, and stretching exercises to increase muscle excursion are all

measures that are likely to

P.290P.291

provide success. The value of injections versus oral NSAIDs, rest, and splint support has not been clarified.![]() Figure 20-2. A: The path of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) from lateral epicondyle to the base of the third metacarpal. B: The center of the epicondyle is the usual pain foci. C:

Figure 20-2. A: The path of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) from lateral epicondyle to the base of the third metacarpal. B: The center of the epicondyle is the usual pain foci. C:

Injection of lidocaine at the painful site. This should eliminate the

pain. The injection is into the muscle origin, below the fascia. D:

Postinjection strength testing usually reveals greater strength after

pain is eliminated (successful injection). (From Putnam MD, Cohen M.

Painful conditions around the elbow. Orthop Clin North Am 1999;30(1):109–118.)

-

-

Muscle–tendon pathway failure results in trigger finger, trigger thumb, and de Quervain’s tenosynovity.

-

The junction

between a specific muscle and its tendon is a potential site of

failure. However, failure or pain at this location is uncommon in the

upper extremity. Achilles tendinitis represents a condition occurring

in the lower extremity. A similar condition does not occur in the upper

extremity with any frequency. Problems along the tendon pathway,

however, do occur. -

Commonly referred to as trigger digits,

snapping of flexor tendon function caused by bunching of the flexor

synovium at the annular one (A1) pulley does occur. This condition is

seen more often in older patients, although a congenital version is

also common. The condition occurs more often in patients with diabetes.

Patients with active tenosynovitis (rheumatoid arthritis) may have a

condition that is often confused for tendon triggering. But, rheumatoid

arthritis and synovitis in other patients can be distinguished from

true trigger digit by the inability to obtain complete active flexion.

This is the result of too much synovium “blocking” the active flexion

of the digit (the excursion of the flexor tendon is blocked). In the

case of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, the problem is focused within the

first dorsal extensor compartment of the wrist. The pathophysiology is

the same, but this condition results in pain and crepitus along the

tendon rather than triggering. The problem and degree of discomfort

varies with time of day and activity. -

Clinical diagnosis

of trigger dysfunction is made based on pain or tenderness, crepitance,

and locking focused at the A1 pulley of a specific digit. -

Laboratory studies

are essentially within normal limits. Radiographic studies are not

generally useful. In the case of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, a special

clinical test (Finkelstein’s) is routinely performed. Finkelstein’s

test is positive if ulnar wrist deviation combined with thumb adduction

and flexion of the metacarpal phalangeal joint reproduces the patient’s

complaint of pain. -

Treatment of

trigger digit and de Quervain’s synovitis includes rest, stretching

exercises, steroid injection into the tendon sheath, and surgical

release of the tendon sheath (3,4,5,6,7,8,11).

If conservative care fails, response to supportive modalities is

variable. In up to 60% of patients, the condition resolves after

steroid injection (12). Surgical release of the sheath is thought to be 95% effective in those who fail to respond to lesser treatments (13).

-

-

Tendon–bone insertion failure results in mallet finger and biceps rupture.

-

Failure at

the distal point of muscle action can occur as a result of attrition or

age-related change, or excessive load. Occasionally, both methods are

involved. Patients are usually seen for diagnosis soon after the

failure occurs. Pain is usually less an issue than is weakness or

dysfunction. -

These conditions are diagnosed

based on findings observed on clinical examination. Laboratory studies

and roentgenographic findings are generally normal, the exception being

when the extensor tendon involved with a Mallet finger pulls off a

piece of the proximal aspect of the distal phalanx (thus, a “bony

Mallet”). Larger tendon ruptures can be further clarified using

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) if there are unclear physical findings. -

Treatment is

based on the ability to reposition the specific insertion and maintain

this in a resting position. For the terminal extensor–mallet finger, 6

weeks of a conservative extension splint treatment is generally

successful (8,10).

Conversely, distal biceps ruptures will not heal without surgery

because the tendon cannot be reliably positioned. However, because the

muscle is a supporting elbow flexor (not the only elbow flexor),

patients who do not require forceful supination (the biceps is the

prime supinator) may choose to forego repair (and tolerate the

functional limitations).

-

-

-

Joint.

Painless, stable joint function is maintained by a combination of

healthy cartilage, retained shape of the joint surface, ligamentous

integrity, and muscle/tendon strength. Change in any of these four

factors begins a process of increasing joint wear and dysfunction.

Aging alone causes changes in the surface of the joint that accelerate

wear. Most arthritic conditions of the arm

are a combination of load, genetics, and history. However, it is

occasionally possible to point to a single event many years earlier

that has gradually led to joint dysfunction. Processes such as

rheumatoid arthritis are usually the sole cause of dysfunction. Even in

these diseases, isolated or cumulative trauma can play a role.-

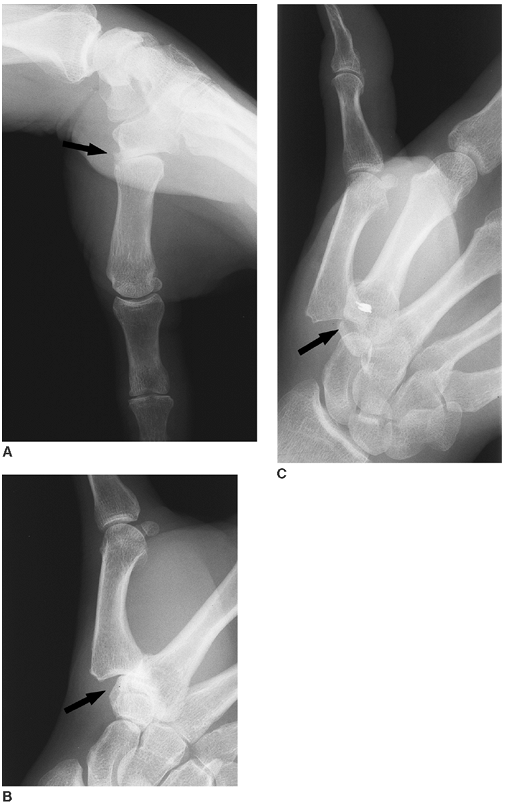

Thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) (Fig. 20-3),

wrist, and elbow DJD occur with decreasing frequency. Thumb CMC DJD may

be the most common site of arthritic presentation. In any of the upper

extremity sites, the most common presenting complaint is pain. To the

degree that a specific joint is unstable, incongruous, or both, motion

and stress aggravate symptoms. Certain activities and prior injury may

predispose to arthritis, but underlying genetics is likely the most

predominant cause. -

Diagnosis is

a combination of history, examination, laboratory study, and plain

radiographs. MRI or computed tomography (CT) methodology is rarely

useful. Most patients complain of pain after activity that is relieved

by rest. Oral NSAIDs are of some benefit. However, care must always be

taken with long-term administration of these medications, particularly

in elderly patients. -

Treatment begins with supportive splints and hot/cold modalities. Hand-based flexible splints are particularly helpful for thumb CMC.

-

At some point, many patients can no longer “tolerate” the pain. This is the time to consider surgery.

Unlike the lower extremity, upper extremity arthritic surgery can offer

patients reliable joint rebuilding procedures without resorting to

joint replacements. An example of such an excisional arthroplasty is

shown in Fig. 20-4. Such procedures report greater than 90% success rate relative to pain relief. -

In the event that first-stage arthritic procedures do not work, newer and increasingly durable total joint replacement options are becoming available for the elbow, wrist, and the proximal interphalangeal joints.

-

-

Bone.

Skeletal support is essential for function of the legs and arms. As

such, immediate change (fracture) or gradual change (e.g., avascular

necrosis, tumor) will alter the function of the arm or leg. Gradual

change is rarely as painful as acute or fracture change in bone

support. This may explain the late presentation for treatment of

patients whose slow change process has progressed to the point at which

curative or reconstructive treatment is no longer an option. Avascular

necrosis of bone is a condition in which presentation and diagnosis are

often delayed. As such, it is a good model to discuss the workup of

bone pain.-

Avascular necrosis, Kienböck’s (lunate) (Fig. 20-4), Presiser’s (scaphoid), and Panner’s (humeral capitellum)

are focal avascular lesions of bone seen in the upper extremity.

Genetics, overload, endocrine and systemic illness, and steroid use may

play contributory roles. Patients usually have pain in the focal area

and, on testing, it is usually possible to document a reduction in

motion. Age of presentation varies from adolescence to late adulthood.

Plain radiographs may reveal a change in bone density. In more advanced

cases, the shape of the bone is altered. Change in shape is a precursor

to diffuse arthritis.-

Conservative treatment

starts with making a definite diagnosis. This is true for any

unexplained pain in bone. If the diagnosis confirms a focal change in

bone vascularity without change in bone shape, initial treatment may

focus on joint support. However, many patients, particularly those with

Kienböck disease, do not gain sufficient pain relief from splints, and

other joint “unloading” treatments are sought. -

Surgical treatments

for these processes can be broken down into treatments that reduce load

on the injured bone segment, debride the injured bone segment, or

replace/excise the injured bone segment. These treatments are likely to

relieve pain in more than 80% of patients; however, full functional

recovery rarely occurs. Figure 20-3. A and B: Loss of normal space between the metacarpal and trapezium typical of basilar joint thumb arthritis. C:

Figure 20-3. A and B: Loss of normal space between the metacarpal and trapezium typical of basilar joint thumb arthritis. C:

After trapezial resection and stabilization of the first to second

metacarpal, a new space for thumb carpometacarpal motion has been

“created.”![]() Figure 20-4. A: Posteroanterior (PA) wrist radiograph showing “collapse” of the lunate. B:

Figure 20-4. A: Posteroanterior (PA) wrist radiograph showing “collapse” of the lunate. B:

Magnetic resonance imaging study of the same wrist from the same point

in time showing essentially no vascular signal within the lunate

marrow. C: PA wrist radiograph showing the capitate “seated” in the lunate fossae after excision of the lunate.

-

-

-

Tumors. The

upper extremity is the site of a variety of tumors, many of which are

rare, some appearing almost exclusively on the hand and the arm, and

still others are common to all regions of the body. Although most

tumors of the upper extremity are benign, few present simple

therapeutic problems. The close anatomic relation of the tumor to the

nerves, vessels, and muscles in the upper extremity presents a great

challenge to the treating surgeon.-

Surgeons who treat hand and upper extremity tumors must be familiar with the wide range of possible diagnoses.

Tumors that look innocent may not be; every mass should be considered

potentially dangerous. This section focuses on primary malignant bony

tumors of the upper extremity: diagnosis, evaluation, pathology, and

treatment recommendations. -

Symptomatic tumors,

especially those that have increased in size, must be diagnosed and

then classified as to stage. The patient’s clinical and family history,

the physical characteristics of the lesion, and diagnostic images

provide information to determine whether the growth is aggressive and

should be “staged.” -

Diagnostic strategies

to accurately stage the lesion should be pursued before obtaining a

biopsy. Appropriate evaluation includes a detailed history and

proficient physical examination, imaging, and laboratory studies. The

history should determine the length of time a lesion has been present,

associated symptoms, and any incidence of family history. Physical

examination requires detailed evaluation of the entire limb and

testing, especially for sensibility, erythema, fluctuance, range of

motion, tenderness, and adenopathy. -

There are a few lesions that have significant associated blood chemistry changes.

These include the elevated sedimentation rate of Ewing’s sarcoma and

the serum protein changes in multiple myeloma. Serum alkaline

phosphatase is elevated in metabolic bone disease and in some

malignancies. A serum immunoelectrophoresis determines whether multiple

myeloma is present. -

Imaging

further aids in determining the location of the tumor and the presence

or absence of tumor metastasis. There are a variety of imaging

techniques that are useful tools.-

Plain films and tomography.

Radiographs are of great importance in the diagnosis of bone tumors.

Excellent technique is required to ensure good resolution of bone and

adequate soft tissue surrounding the lesion. Plain films are the

benchmark in predicting presence and location of bone involvement.

Tomography or CT affords improved resolution. -

MRI has

recently developed as one of the more important tools for diagnosing

bone tumors. It offers excellent delineation of soft-tissue contrast as

well as the ability to obtain images in axial, coronal, and sagittal

planes. Additionally, MRI can visualize nerve, tendon, and vessels and,

with advanced protocols, cartilage can also be evaluated.

-

-

Classification of lesions.

Correct treatment must always take into consideration the location and

size of the tumor, the histologic grade and clinical behavior, and the

potential for metastasis. If a lesion increases in size or becomes

symptomatic, or if the physical or radiographic appearance suggests an

aggressive lesion, appropriate staging studies including a tissue

diagnosis (biopsy) must be obtained. -

Specific tumors

-

Benign

-

Lipoma. This

common tumor occasionally presents in the hand or wrist as a firm mass

within a nerve or vascular passageway. As such, it may be associated

with carpal tunnel syndrome. Its nature may be suspected based on

clinical examination alone (mass). To understand its dimensions and

relationship to adjacent tissues, an MRI scan is usually obtained.

Excision (marginal) is the treatment of choice. -

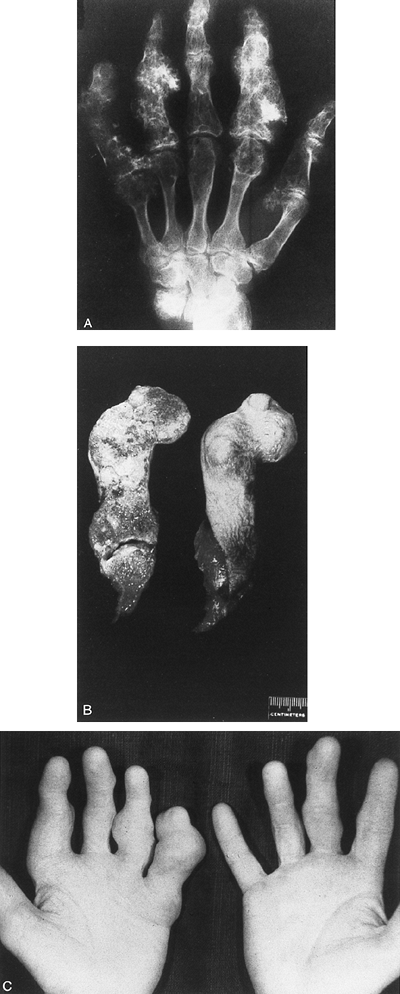

Enchondromas (Fig. 20-5)

of the hand are common; they are sometimes multiple and often present

after a fracture. Initial treatment in this circumstance is aimed at

satisfactory fracture healing. They can clinically be confused with

osteochondromas. Radiographic examination easily differentiates the two

processes. Most randomly identified lesions can be observed; any lesion

associated with pain or increasing size in adulthood should be more

carefully studied. Treatment is either observation or intralesional

excision. Occasionally, previously benign lesions recur or undergo

malignant transformation (Fig. 20-5). Any such lesion should be biopsied and carefully considered for wide excision.

-

-

Malignant

-

Melanoma. The hand, wrist, and forearm are common sites of melanoma. Any change in a pigmented lesion warrants biopsy.

Figure 20-5. A: Posteroanterior radiograph showing bone changes consistent with multiple enchondromas. B: Longitudinal section of the small finger. Pathology seen was consistent with low-grade chonorosarcoma. C:

Figure 20-5. A: Posteroanterior radiograph showing bone changes consistent with multiple enchondromas. B: Longitudinal section of the small finger. Pathology seen was consistent with low-grade chonorosarcoma. C:

Preoperative clinical photo showing multiple digit enlargements. In

this case, the patient noted rapid enlargement of the small finger

during several months before surgery. (From Putnam MD, Cohen M.

Malignant bony tumors of the upper extremity. Hand Clin 1995;11(2):265–286.) -

Osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma.

Malignant bone lesions do occur in the arm. Most distal lesions are

likely to represent degenerative change of benign processes (Fig. 20-5).

Any bone or enlarging soft-tissue mass must always receive a complete

evaluation (staging and biopsy) leading to a definitive diagnosis.

P.296P.297 -

-

-

Metastasis.

Lesions from elsewhere appearing as metastasis are the most common form

of malignancy in the hand. This should be kept in mind, particularly

for the patient who is not known to have a malignancy and whose lesion

is not in keeping with local origin. A search for the primary tumor is

appropriate.

P.295 -

-

Other factors: Workmen’s compensation.

The hand is often the first tool in and last tool out of a dangerous

situation. As such, it is the frequent site of workplace injuries (14).

Not all injuries are clearly documented. It is the physician’s

responsibility to remain the patient’s advocate while at the same time

remaining an objective observer. Occasionally, these tasks are in

conflict. Three simple rules apply in these situations:-

Remain a dispassionate recorder of medical facts.

-

Search for an accurate diagnosis.

-

Offer no treatment without a specific diagnosis.

-

JN, Keller RB, Simmons BP, et al. Maine carpal tunnel study: outcomes

of operative and nonoperative therapy for carpal tunnel syndrome in a

community-based cohort. J Hand Surg (Am) 1998;23:697–710.

JP, Fink K, Sullivan SD. Conservative versus surgical treatment of

mallet finger: a pooled quantitative literature evaluation. J Am Board Fam Pract 1998;11:382–390.

G, Herbert R, Hearns M, et al. Evaluation and management of chronic

work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the distal upper extremity. Am J Ind Med 2000;37:75–93.

Quervain F. On a form of chronic tendovaginitis by Dr. Fritz de

Quervain in la Chaux-de-Fonds. 1895. Illgen R, Shortkroffs, trans. Am J Orthop 1997;26:641–44.