FRACTURES OF THE METACARPALS AND PHALANGES

The skeleton of the hand is inherently related to adjacent joints,

overlying gliding tendon units, and deforming muscle forces. Although

failure to gain union following a metacarpal or phalangeal fracture is

rare, concomitant problems present a different story. Preventing

angular or rotational deformity, articular stiffness, and tendon

adhesion challenges even the most experienced surgeon (34).

As Charnley recognized: “The reputation of a surgeon may stand as much

in jeopardy from this injury [phalangeal fracture] as from any fracture

of the femur” (13).

can be successfully treated without surgery. A nonanatomic outcome,

however, can jeopardize overall hand function, leading at times to a

prolonged and major disability (11). Therefore, it is important to identify the fractures that require operative treatment (Table 40.1),

the surgical approaches that minimize soft tissue adhesions, and the

postoperative management that best encourages joint mobilization and

avoids soft tissue contracture (5).

|

|

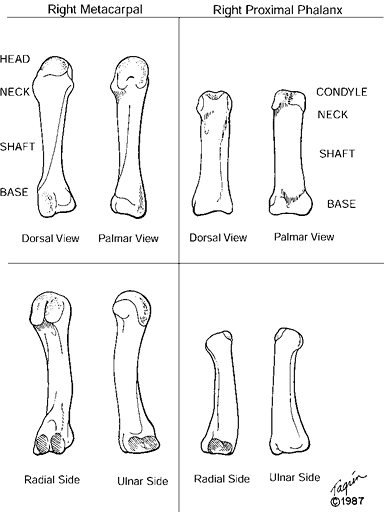

Table 40.1. Phalangeal and Metacarpal Fractures Often Requiring Internal Fixation

|

through the metacarpals, having a keystone in the metacarpophalangeal

joints. The rigid central pillar of the hand passes through the second

and third metacarpals, and the mobile carpometacarpal joints of the

thumb, ring, and little rays permit mobility at the borders of the

hand. The deep transverse metacarpal ligaments connect the four

metacarpals of the hand and provide internal support, particularly for

the long and ring metacarpals. The extrinsic flexor tendons exert a

flexion and adduction force on

the

distal metacarpals that is enhanced by the short but powerful intrinsic

tendons that pass on the palmar side of the midaxis of the

metacarpophalangeal joint.

phalanges are isolated skeletal units and are subject to the deforming

muscle forces of both the extrinsic flexor and extensor tendons and the

intrinsic tendons. The proximal parts of the proximal and middle

phalanges are subject to strong flexor forces, whereas the more distal

shafts and neck tend to go into hyperextension because of the pull of

the extensor mechanism.

hand function by the complex configuration of the carpometacarpal joint

as well as the transmission of power through the numerous tendon

insertions. When the integrity of the thumb skeleton has been disrupted

or deformed secondary to fracture malunion, the balance of these forces

is disturbed, leading to deformity.

views—anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique. Check rotational and

angular alignment by evaluating the relationship of the fingernails to

each other in both extension and flexion. It may be necessary, after

careful assessment of the neurovascular status, to anesthetize the

digit or hand to better assess rotational alignment and fracture

stability.

required. Kirschner wire fixation, particularly when placed

percutaneously, is an excellent method in single or adjacent metacarpal

or phalangeal fractures. Use of this technique requires expertise in

wire placement and image intensification (2,4,24,37).

various methods, including interosseous wire and tension band wire

techniques as well as more stable miniscrews and plates (3,5,6 and 7,9,14,15,19,23,26,27,29,35,38,40,43,46,50).

The greater the severity of the combined skeletal and soft tissue

injury, the more important it becomes to achieve stable fixation that

allows early mobilization.

joint motion and minimizing adhesions of the gliding structures, such

as the tendons and joints. Under the supervision of a hand therapist,

static and dynamic splints, antiedema measures such as Coban wraps, and

active assisted range-of-motion exercises have proved an effective

means of regaining motion and avoiding joint contracture, even in

severe combined skeletal and soft tissue injuries of the hand.

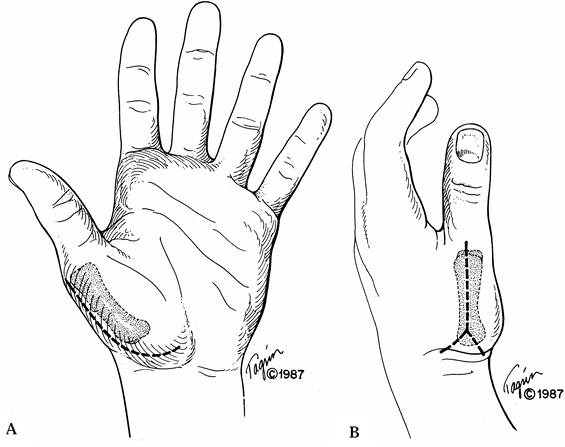

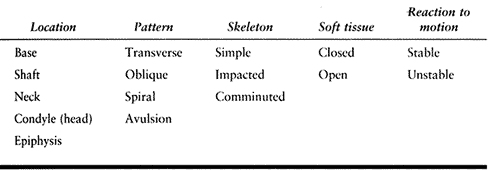

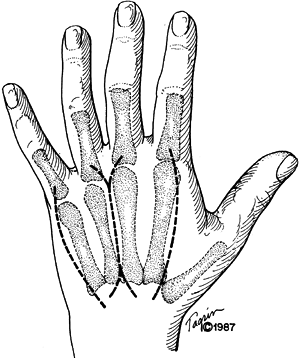

fractures call for specific methods of treatment depending on the

fracture pattern and location. Features used to classify

phalangeal and metacarpal fractures include location, fracture configuration, soft tissue integrity, and inherent stability (Table 40.2). These tubular bones are divided into base, shaft, neck, and articular heads (Fig. 40.1).

In children, the epiphyseal zones are found at the bases of the

phalanges and the head and neck of the metacarpals. The thumb

metacarpal differs in that the epiphyseal center is found at the base.

|

|

Figure 40.1. Anatomy of the metacarpal and phalanx.

|

|

|

Table 40.2. Functional Fracture Classification

|

transverse or serpentine approaches on the dorsum of the hand, as they

limit trauma to the venous and lymphatic systems (Fig. 40.2).

|

|

Figure 40.2. Dorsal surgical approaches to the metacarpals.

|

-

Approach the long and ring metacarpals

through a longitudinal incision between the bones, using a Y-shaped

extension if necessary to provide more proximal or distal exposure.

Approach the border metacarpals individually through longitudinal

incisions, with curving extensions as needed. -

Facilitate exposure of the distal

metacarpal shafts, neck, or head by cutting through the juncturae

tendinae linking the common extensor tendons. Tag these for later

reapproximation with 5-0 nylon suture. -

Next, incise the junction of the sagittal

band and extensor tendon to permit access to the metacarpophalangeal

joint. Reapproximate it with fine nonabsorbable suture. -

At the shaft level, incise the periosteum

carefully, leaving as much attached as possible and preserving the

origins of the interosseous muscles. Gently expose the fracture site

and remove the hematoma by irrigation with a small-bore needle and use

of a dental pick. -

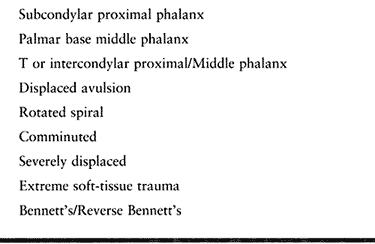

Surgical approaches to the thumb

metacarpal are most often required for intraarticular fractures at the

base. The palmar approach described by Gedda and Moberg starts

proximally at the wrist crease and extends distally along the

metacarpal shaft (Fig. 40.3) (22).![]() Figure 40.3. Surgical approaches to the thumb metacarpal: palmar (A) and dorsal (B).

Figure 40.3. Surgical approaches to the thumb metacarpal: palmar (A) and dorsal (B). -

Elevate the thenar muscles

subperiosteally off the metacarpal shaft to give good exposure to the

palmar aspect of the carpometacarpal joint. This approach is

particularly effective for Bennett fractures with small palmar

fragments. The radiodorsal approach is preferred for fractures that

extend onto the proximal metacarpal shaft. -

Make the incision along the radial edge

of the metacarpal. Identify and preserve crossing branches of the

radial sensory nerve as well as the insertion of the abductor pollicis

longus tendon. Elevate the thenar muscles subperiosteally off the

shaft, if necessary, to improve exposure of the base.

-

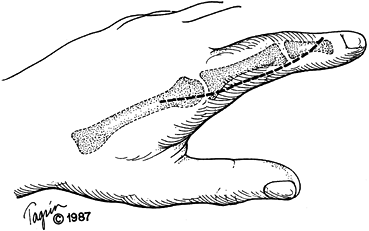

Approach the proximal and middle phalanges through dorsolateral or midaxial incisions (Fig. 40.4).

Figure 40.4. Surgical approaches to the phalanges.

Figure 40.4. Surgical approaches to the phalanges. -

Elevate the dorsal skin flap off the

paratenon of the extensor tendon. Preserve the dorsal venous arcade

whenever possible. Pay careful attention to preserving the paratenon

and periosteum to avoid later adhesions between the phalanx and tendon. -

If more distal exposure of the shaft is

necessary, incise the transverse retinacular ligament to allow further

mobilization of the extensor mechanism. Mark this interval for later

reapproximation. -

Approach the proximal interphalangeal

joint straight dorsally between the central extensor tendon and the

lateral band or between the lateral band and the collateral ligament.

Occasionally, additional exposure can be obtained by osteotomizing the

insertion of the central slip onto the base of the middle phalanx and

reflecting the tendon proximally. The insertion can later be secured

with a tension wire or small screw. -

Use a complete or partial H incision to

gain access to the head of the middle phalanx or distal interphalangeal

joint. Split the extensor tendon longitudinally or in a Z fashion to

expose the joint.

the mobile ring and little, require a careful assessment of any

intraarticular involvement. These fractures are often the result of

crushing injuries and are associated with fracture-dislocations at the

carpometacarpal joints. Accurate reduction may offset later

posttraumatic arthrosis, particularly

in

the ulnar metacarpals. Achieve reduction with longitudinal traction and

Kirschner wire fixation from little to ring metacarpal, metacarpal to

hammate or capitate, or both. If comminution is extensive, surgical

options are indirect reduction with a mini–external fixator or open

reduction with a condylar plate. Approach the treatment of fractures at

the base of the little metacarpal in a manner similar to that for

fractures of the thumb carpometacarpal joint.

positioned with the wrist slightly extended, metacarpophalangeal joints

flexed 80° to 90°, and interphalangeal joints free for movement. Start

motion at the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints within the

first week. Remove percutaneous pins after 4 weeks, and begin

grip-strengthening exercises.

is not achieved. It can be more symptomatic in the ulnar metacarpals

because these carpometacarpal joints are so mobile. Arthrodesis may

eventually be necessary.

progressed considerably since the 1930s, when virtually all metacarpal

fractures were treated by bandaging over a roller bandage with little

or no attempt to correct displacement. Angulation, shortening, or

rotation that cannot be controlled by plaster support requires internal

fixation. In addition, fractures associated with soft-tissue crush or

open injuries are better managed with internal fixation (Table 40.3).

|

|

Table 40.3. Indications for Internal Fixation—Metacarpal Shaft

|

Potential problems are inherent with the placement of the wire through

the metacarpophalangeal joint capsule or the extensor tendon mechanism.

For multiple transverse fractures or those associated with crushing

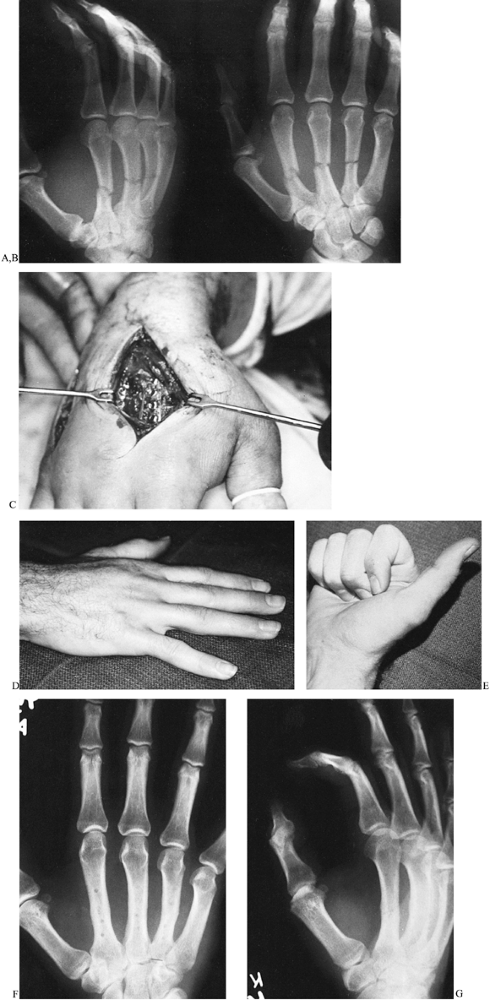

injuries, we prefer dorsally placed tension band plates (Fig. 40.5),

generally using four-hole one-quarter tubular plates with 2.0- or

2.7-mm screws. Some compression can be gained at the fracture line by

drilling eccentrically in the farthest holes from the fracture line and

placing both screws simultaneously (29). If

comminution is noted at the fracture line, use a longer plate and place

a small amount of cancellous bone graft—readily obtained from the

distal radius—in the zones of comminution.

|

|

Figure 40.5.

A 24-year-old laborer’s dominant right hand was crushed by a dumpster. There was extensive soft-tissue trauma associated with three metcarpal shaft fractures. A,B: Anteroposterior and oblique views revealed transverse metacarpal shaft fractures. C: Through two longitudinal incisions, one-quarter tubular plates and 2.7-mm screws were applied. D,E: Full flexion and extension were achieved within 6 weeks despite the extensive soft-tissue crush. F,G: Anteroposterior and oblique radiographs 6 months after plate removal. |

The length of these fractures should be at least three times the

diameter of the shaft at the level of the fracture to permit adequate

fixation with screws alone. The screws should distribute

interfragmentary compression evenly along the entire fracture length.

Place one screw perpendicular to the fracture line and one

perpendicular to the shaft to ensure distribution of compression and

offset shear stresses on the implants. With short oblique fractures, a

single screw cannot withstand the rotatory, shear, or bending stresses

of normal activity. These stresses must be neutralized by a plate to

allow early mobilization (Fig. 40.7).

|

|

Figure 40.6. A 27-year-old surgical resident sustained spiral malrotated second and third metacarpal shaft fractures in a sporting event. A: Oblique radiograph shows the rotatory displacement of the metacarpal shaft fractures. B: Clinically, malrotation was readily apparent. C:

The large fracture surfaces proved amenable to interfragmentary screw fixation using 2.7-mm and 2.0-mm screws. Note the arrangement of the screws to offset shear and rotational stresses. The patient made a full functional recovery. |

|

|

Figure 40.7.

A 35-year-old laborer sustained a severe crush injury to his left hand. In view of the massive soft-tissue trauma, rigid internal fixation was chosen to rapidly mobilize the hand. An interfragmentary screw was placed through a small T-plate. |

metacarpal shaft fractures has been shown in recent studies to yield

excellent results for union and total arc of hand motion (44,48).

Traditionally, external fixation has been used for complex comminuted

and open fractures, where the principles of indirect reduction and

minimization of soft tissue stripping are advocated.

in Dacron batting dressing, and support it in a plaster splint. Begin

active assisted range-of-motion exercises 48 to 72 h after surgery.

Coban wraps around the digits and hand effectively control

postoperative swelling. Take radiographs at 1, 3, and 6 weeks after

surgery. The patient should be able to start light manual activities at

3 weeks and unrestricted activities by 6 to 8 weeks.

is rigid enough to support the fracture during rehabilitation. Leaving

the hand immobile until fracture union after an extensive surgical

exposure can result in tendon adhesions or joint contracture.

Unforeseen comminution or longitudinal fracture lines may cause the

unwary surgeon to place

the

screws in unsound bone. Study the fracture pattern once the hematoma

has been cleared and before the actual reduction. When a screw is loose

because its threads have been stripped, achieve stable fixation by

placing a larger screw, redirecting the screw, or using a longer plate.

Converting to Kirschner wire fixation with tension loops of

stainless-steel wire is also effective when rigid fixation is

inadequate (18).

result of direct impact. The deformity is generally palmar angulation

of the distal fragment; rarely, malrotation may also be present.

Excessive flexion of the distal fragment can lead to hyperextension at

the metacarpophalangeal joint, interference with grip, and pain over

the metacarpal head in the distal palm. Although most would agree that

more than 10° of palmar angulation is unacceptable in the index and

long metacarpals because of their immobile carpometacarpal joints, some

controversy surrounds fractures of the metacarpal necks of the ring and

little fingers. Several authors have reported acceptable functional

results with flexion deformities of at least 70° in the little finger (16,30,31).

We believe that reduction should be considered for angulation beyond

30° to 40° in the little finger and beyond 20° to 30° in the ring

finger (49,53).

of flexing the proximal interphalangeal joint and using the proximal

phalanx to push the metacarpal head into position. Reduction by direct

pressure on the prominent palmar surface of the head with

counterpressure on the dorsum of the shaft works equally well.

Immobilization in this position is not acceptable to hold the reduction

in place because of the risk of joint contracture or skin necrosis.

effective in stabilizing metacarpal neck fractures, particularly of the

little and ring metacarpals. The wires, generally 0.035 in., can be

introduced transversely, proximal and distal to the fracture and into

the adjacent metacarpal, obliquely across the fracture, or

longitudinally through the flexed MP joint. Place a 14-gauge hypodermic

needle against the metacarpal to function as a pin guide. These methods

of treatment carry a risk of permanent metacarpophalangeal

joint stiffness when the pins transfix the extensor mechanism.

-

We prefer to introduce the Kirschner

wires from the base of the metacarpal. Using image intensification,

make a small transverse incision over the dorsoulnar aspect of the base

of the metacarpal. Create a small window in the metacarpal base. Bend a

0.045-in. Kirschner wire into a gentle arc and hammer it distally up

the shaft while holding the fracture reduced in the 90–90 position. The

pin should extend into the subchondral bone of the head (Fig. 40.8). Figure 40.8. A: A 21-year-old musician sustained a completely displaced metacarpal neck fracture of his dominant right hand. B,C: Three 0.045-mm Kirschner wires were inserted through a small opening in the base of the metacarpal. D–F:

Figure 40.8. A: A 21-year-old musician sustained a completely displaced metacarpal neck fracture of his dominant right hand. B,C: Three 0.045-mm Kirschner wires were inserted through a small opening in the base of the metacarpal. D–F:

Motion exercises were started after 2 weeks, and full range of motion

and healing were observed at 7 weeks. Pins were removed after 10 weeks. -

Introduce a second pin if motion is felt

at the fracture. Cut the pin(s) just beneath the skin and apply an

ulnar gutter splint with the metacarpophalangeal joint maintained in

flexion. Gentle motion may be initiated 2 weeks after surgery. -

Percutaneous pins, placed sagittally from

dorsal to palmar and bonded together by methylmethacrylate, have also

been advocated as a reliable means of holding the reduction without

opening the fracture site (45). The method,

however, carries the risk of the extensor mechanism being transfixed by

the pins or pin track sepsis. This technique is perhaps best reserved

for fractures associated with soft tissue injury or bone loss. -

Reserve open reduction and internal

fixation for grossly displaced fractures, fractures associated with

extensive soft tissue trauma, or fractures seen too late for

manipulative reduction. Because of the proximity of these fractures to

the joint and extensor mechanism, we prefer crossed Kirschner wires

looped with a stainless-steel wire as a tension band (Fig. 40.9).![]() Figure 40.9.

Figure 40.9.

A 46-year-old woman was thrown from a horse, sustaining multiple

injuries. Anteroposterior radiograph shows a fifth metacarpal neck

fracture treated by two crossed Kirschner wires and a dorsal

stainless-steel loop acting as a tension band. -

Place two 0.035-in. or 0.028-in.

Kirschner wires, either criss-crossing the fracture or parallel to the

fracture, dorsal to the midaxis of the bone. Place a 28-gauge stainless

steel wire dorsally over the fracture and just under the points of the

wires. -

Initiate motion 48 to 72 h after surgery. The Kirschner wires can be removed under local anesthesia in the office.

metacarpal neck fractures lies in the potential for stiffness of the

metacarpophalangeal joint. Avoid open reduction if possible;

percutaneous techniques are preferable. We generally bury the Kirschner

wires just under the skin to avoid pin track infections.

fractures are intraarticular fractures seen most often in young adults

as a result of athletic injury (39). They vary

from an osteochondral fracture to two- or three-part fractures in a

sagittal or coronal plane to grossly comminuted fractures (28).

lateral tomography to determine the operability of the fracture as well

as the location of the fragments. For nondisplaced as well as very

comminuted fractures, splint support and protected motion are

preferable.

-

Through a dorsal approach, open the joint

capsule longitudinally. Meticulous handling of the small fracture

fragments is imperative to avoid further fragmentation or

devascularization. Preserve any soft tissue attachments. -

Provisionally stabilize the fracture with 0.028-in. Kirschner wires, verifying the reduction with anteroposterior,

P.1322P.1323

lateral, and oblique radiographs. As a general rule, if the fracture

fragment is larger than two to three times the diameter of the screw

head, internal fixation with 1.5-mm miniscrews is preferred. -

If secure fixation can be achieved, early mobilization of this joint injury can be started.

-

With smaller fragments, Kirschner wire

fixation is recommended. With impacted fragments, cautious elevation

and support with cancellous bone graft obtained from the end of the

radius can restore the anatomic profile of the metacarpal head (Fig. 40.10). Figure 40.10. A 22-year-old man suffered an open metacarpal head fracture. A: Anteroposterior radiograph shows a displaced split fracture. B:

Figure 40.10. A 22-year-old man suffered an open metacarpal head fracture. A: Anteroposterior radiograph shows a displaced split fracture. B:

Irrigation, debridement, open reduction, and internal fixation with two

1.5-mm screws were performed. This patient began early motion after 1

week to allow for wound healing.

internal fixation. Screw fixation, if rigid, will permit protected

motion 48 to 72 h after surgery. Kirschner wire fixation should be held

in a splint with the metacarpophalangeal joint flexed 70° for 10 to 14

days before motion is started.

to avascular necrosis, loss of reduction, metacarpophalangeal joint

stiffness, or posttraumatic arthrosis. Proper preoperative assessment,

particularly with tomography, may prevent the surgeon from entering

into an unduly difficult reconstruction.

base. The distinction between intraarticular and extraarticular

fractures is important, particularly in that the thumb metacarpal will

tolerate at least 30° angulation without noticeable deformity or

altered function (25). The carpometacarpal

joint of the thumb is critical for thumb and hand function, however,

and inadequate treatment can lead to a substantial hand disability (12).

Special radiographic views, including tomography or the Robert

anteroposterior view taken with the hand in maximum pronation so that

the dorsum of the thumb is against the radiographic plate, are often

required to assess the fracture pattern accurately.

The small palmar fragment remains attached to the trapezium and second

metacarpal by the stout anterior oblique ligaments, while the shaft of

the metacarpal is pulled proximally and radially, allowing the abductor

pull to increase the deformity at the base.

-

With image intensification, attempt

closed reduction by longitudinal traction, pronation, and compression

on the base of the metacarpal. If an anatomic reduction can be

realized, percutaneous Kirschner wire fixation using 0.045 wires will

guard against redislocation. The use of a 14-gauge hypodermic needle

facilitates the placement of the Kirschner wires into the tubular shaft

of the metacarpal. -

Direct one wire into the second

metacarpal and a second into the trapezium. Cut the wires just under

the skin and apply a thumb spica cast for 6 weeks (Fig. 40.11). Figure 40.11.

Figure 40.11.

A displaced Bennett’s fracture was treated successfully by a closed

reduction and percutaneous Kirschner wire fixation. Image

intensification facilitated the pin placement. -

If an anatomic reduction cannot be

obtained or maintained, open reduction and internal fixation are

required. Through the palmar approach of Gedda and Moberg, reduce the

fracture and gently hold it with a bone-reduction clamp while making

provisional fixation with Kirschner wires. -

Introduce a 2.0- or 2.7-mm cortical screw

from a dorsal direction into the fragment, placing the gliding hole in

the metacarpal shaft. Use the half-threaded 4.0-mm cancellous screw

only if adequate fixation cannot be achieved, as this type of screw may

be difficult to remove. -

If small Kirschner wires are used,

support the fixation by an additional Kirschner wire between the thumb

metacarpal and second metacarpal as well as by a thumb spica cast for 4

to 6 weeks. With stable screw fixation, protected motion may be

initiated 48 to 72 h after surgery.

Y-shaped intraarticular fracture, but significant comminution is far

more common. Preoperative tomography is exceedingly important to

determine the operability of these fractures. Often they are impacted

and require support with a cancellous bone graft. Place a small T or L

plate on the dorsal surface of the metacarpal to support the

reconstruction (Fig. 40.12) (19).

|

|

Figure 40.12. A 42-year-old man fell and sustained a closed intraarticular Rolando fracture of the base of his right dominant thumb. A: Anteroposterior radiograph shows the fracture configuration. B: The fracture was openly reduced and internally fixed with a 2.0-mm interfragmentary screw as well as a small L plate. C: The fracture healed, and the functional recovery was excellent.

|

screw-and-plate fixation, use Kirschner wire fixation with cancellous

bone graft and mini–external fixation stabilizing the thumb metacarpal

to the index metacarpal. This technique maintains distraction on the

joint while healing occurs (Fig. 40.13) (10).

|

|

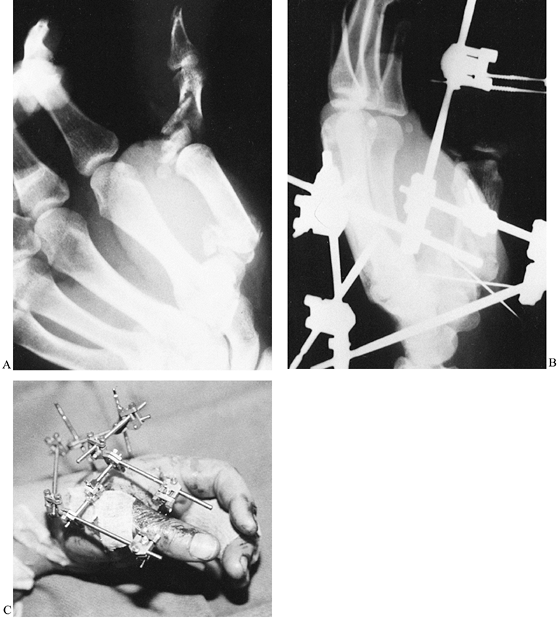

Figure 40.13. A 30-year-old tool-and-die worker’s dominant thumb was caught in a lathe, causing extensive skeletal and soft-tissue trauma. A:

Anteroposterior radiograph shows a comminuted intraarticular fracture at the base of the metacarpal as well as a severe fracture of the proximal phalanx. B: Following repair of the flexor pollicis longus and the radial digital nerve and artery, an open reduction and internal fixation of the base of the metacarpal was accomplished. The impacted articular fragments were reduced, held with 0.035-mm Kirschner wires, and supported by distal radius cancellous bone graft. A mini-external fixation unit was placed to prevent settling of the joint reconstruction, to maintain the first webspace, and to maintain reduction of the proximal phalanx fracture. C: Rehabilitation of the hand progressed with the fixator in place. |

result early in abduction deformity of the thumb metacarpal, leading to

posttraumatic arthrosis. Miniscrew-and-plate fixation should be used

only by a surgeon experienced in these techniques because inadequate

fixation can lead to collapse of the articular restoration and to

substantial later disability. When approaching this area, avoid

prolonged intraoperative traction on the branches of the radial sensory

nerve, which can result in a distressing neuritis.

Certainly many are nondisplaced, stable, and readily treated by

splintage or buddy straps, and others are easily reduced and held by

external plaster support. Because of the intimate relationship of the

tendons and joints to the phalangeal shaft, however, certain unstable

phalangeal fractures—including displaced, comminuted, spiral, or short

oblique—require internal fixation to ensure anatomic alignment and

restore functional mobility.

|

|

Figure 40.14. A 37-year-old cardiologist sustained a closed fracture of his ring finger in a basketball game. A,B: Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs revealed a comminuted fracture with angular and rotatory malalignment. C,D: Treatment consisted of closed reduction, percutaneous longitudinal Kirschner wire placement, and plaster cast for 3 weeks. E: The fracture healed in near-anatomic position, and full function resulted.

|

-

After appropriate anesthesia, apply

longitudinal traction through the middle phalanx and flex the

metacarpophalangeal joint 60° to 70° with the proximal phalanx flexed

about 45° (4). -

Make angular and rotatory corrections at

this juncture. If swelling is not profound, anatomic landmarks for

insertion of Kirschner wires include the flare of the head of the

proximal phalanx and the proximal palmar skin crease, which also lies

under the flare (24). The size of the Kirschner wire is determined by the location of the fracture and the size of the bone. -

Stabilize fractures of the base,

transverse shaft, and neck by one 0.045-in. or two 0.035-in. Kirschner

wires placed longitudinally through the metacarpal head, preferably to

one side of the extensor tendon and extended distally into the

subchondral bone at the condylar levels. Verify the reduction and wire

placement by image intensification, followed by standard radiographs in

three views. -

Apply either dorsal and palmar splints or

a plaster cast. Take care that the plaster does not come into contact

with the pins, which are left protruding through the skin for ease of

removal. -

Remove the cast at 3 weeks and the pins

at that time or at 4 weeks, depending on the radiographic appearance.

Initiate active assisted range-of-motion exercises under a therapist’s

supervision.

satisfactorily stabilized with parallel Kirschner wires placed across

the fracture site. For the index and little fingers, introduce the

wires from the radial and ulnar sides, respectively, and leave them

protruding through the skin for ease of removal. Open reduction and

internal fixation are required for fractures that cannot be well

reduced by manipulative reduction, those associated with soft tissue

trauma, and those seen late.

-

Approach the shaft through the interval

between the lateral band and common extensor tendon. More distal

exposure may require division of the transverse retinacular ligaments,

which are marked for later reapproximation. Spiral fractures for the

most part are amenable to interfragmentary screw fixation using 1.5-mm

screws. -

Directing one screw perpendicular to the

phalangeal shaft and a second perpendicular to the fracture line

protects the fracture from shear and rotatory stresses. Countersink the

holes to keep the screw heads from interfering with the overlying

gliding structures. If the fracture is a short oblique pattern, the

interfragmentary screw will require a neutralization plate to protect

against shear or rotational forces, even though the plate may prove to

be bulky.

Application is straightforward and requires little in the way of

instrumentation, and the fixation is less bulky than plates. The

disadvantages, however, include the failure to gain a tension band

effect if the wire loop is placed in the midaxis of the shaft; also,

the oblique Kirschner wire required to neutralize rotational forces may

interfere with gliding of the lateral band. A wire loop placed on the

dorsal aspect of the shaft in association with transverse or crossed

Kirschner wires effectively functions as a tension band (23).

|

|

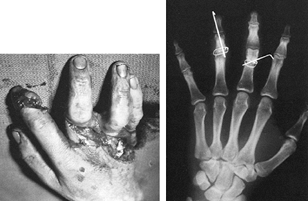

Figure 40.15.

A 19-year-old right-hand-dominant student caught his right hand in a table saw. Extensive soft-tissue and skeletal disruption resulted. The phalangeal fractures in the long and ring figers were fixed with an interosseous wire as well as an additional Kirschner wire for rotational control. Revascularization of the involved digits was also required. |

-

Start the technique of interosseous wire

fixation with the placement of two parallel drill holes with a 0.035

Kirschner wire just dorsal to the midaxis of the shaft and just

proximal and distal to the transverse fracture line. Pass a 20-gauge

hypodermic needle into each drill hole to facilitate the passage of a

26-gauge stainless-steel wire through the drill holes, with the free

ends facing the surgeon. Alternatively, with the hub cut off sharply,

use the hypodermic needle to drill the holes. -

At this juncture, pass a 0.035-in.

double-ended Kirschner wire obliquely from within the fracture site

distally out through the skin. With the fracture held reduced, drive

the Kirschner wire into the proximal fragment. -

Then firmly pull the interosseous wire,

twist it manually for three or four turns, and then twist it with a

needle holder until the twist is seen to bend gently. Stress the

fracture manually to verify the stability of the fixation and cut the

twist short and bend it either against the shaft or into a drill hole

in the shaft (Fig. 40.15).

motion 48 to 72 h after surgery. Coban wraps help reduce digital

swelling, and static and dynamic splints help restore mobility while

preventing potential joint contracture. Kirschner wires can usually be

removed at 3 to 4 weeks. We prefer to leave interfragmentary screws in

place unless they prove bothersome.

stripping, inadequate or loose internal fixation, and prolonged

immobilization can cause loss of position or motion (20,47).

Because of the inherent relationships of the tendons to the phalangeal

skeleton, screws placed in the anteroposterior plane can risk tendon

rupture if they protrude excessively from the bone (18).

Displaced phalangeal articular fractures, particularly basilar avulsion

types and the condylar or bicondylar variants, often require open

reduction and internal fixation, as the fragments are small and

frequently are not only separated but also rotated (3). Obtain three radiographic views to visualize the fracture and degree of displacement adequately.

mechanism at the bases of the phalanges. If there is displacement or

rotation, internal fixation is advised. Tension band fixation using a

28-gauge stainless-steel wire is effective for avulsion fractures such

as bony gamekeeper’s thumb fractures, lateral avulsion injuries, and

dorsal avulsions of the middle phalanx (6,36).

exposed to allow the fracture line and the joint to be visualized. Take

care to avoid dissection of the soft tissue attachments to the

condyles. We recommend either a dorsal or midaxial incision at the

proximal interphalangeal joint level; use a modified H incision over

the distal interphalangeal joint. For extremely displaced bicondylar

fractures or those with associated impaction of the base of the middle

phalanx, we have on occasion obtained added exposure by osteotomizing

the insertion of the central slip, which is later replaced and secured

with a tension band wire.

condylar fractures may be held by directing the screw from the opposite

cortex, thereby avoiding devascularization of the collateral ligament

or fragment by the relatively large screw head.

trauma, have a high risk of residual joint stiffness. For this reason,

we try to obtain fixation rigid enough to permit early postoperative

joint mobilization. Securely fix both condyles with a lag screw placed

through a mini–condylar plate along the side of the shaft. This plate

is designed to sit on the side of the shaft, thus avoiding interference

with the glide of the extensor mechanism.

interphalangeal joints are also difficult to treat and have a high

incidence of residual stiffness or joint subluxation. The force-couple

technique described by Agee (1) has the

advantage of maintaining joint reduction while encouraging joint

mobility. Not only does it help mold a new fibrocartilaginous joint

surface on the base of the middle phalanx but it also avoids

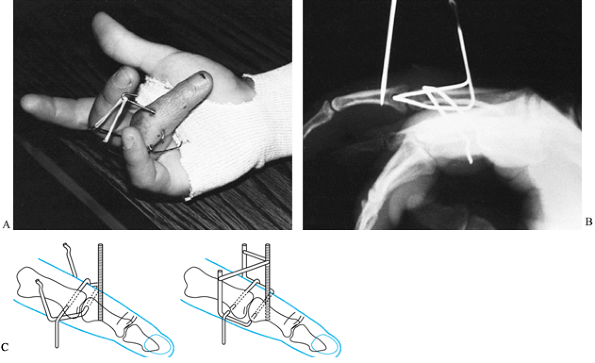

contracture of the soft tissues (Fig. 40.16) (1).

|

|

Figure 40.16. A fracture-dislocation of the PIP joint was treated with a closed reduction and application of Agee tracture. A: Clincal appearance with traction in place. B: Radiographic appearance, showing reduction. C: Placement technique (left) before reduction and (right) after reduction, with rubber-band traction assembly in place.

|

-

Bend the distal transverse Kirschner wire

90° on both sides to pass proximally and below the proximal Kirschner

wire and bend it again 90° dorsally. -

Next, bend the proximal transverse wire

90° palmarly on either side of the finger extending palmarward and

connect it beneath the digit by a strip of adhesive tape. -

Finally, connect the vertical threaded

Kirschner wire with the vertical arms of the distal transverse

Kirschner wire with a small rubber band, creating a “force couple” that

reduces the dislocation. -

Encourage the patient to begin active

motion and leave the device in place for at least 4 weeks and

preferably for 6 weeks. A spring-loaded dynamic external fixator using

the same principles of force coupling has been effective as well (32).

difficult hand injuries to treat because of their small size,

precarious vascular supply, and propensity for associated soft-tissue

contracture. Excessive exposure and soft tissue stripping, inadequate

skeletal fixation, or fragmentation of the condylar fragments results

in loss of joint mobility, arthrosis, or avascular necrosis. Careful

preoperative planning is essential for proper operative management.

phalanges is a challenge because of the constant struggle between the

achievement of skeletal union and the maintenance of soft tissue

integrity and function. The techniques outlined seek to accomplish both

goals. An underlying tenet is that the greater the soft tissue injury,

the greater the need for stable fracture fixation to allow early

motion. For best results, pay careful attention to edema control as

well as the proper positioning and therapy of the uninjured portion of

the hand.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.

K, Snellen JP. Internal Fixation of Metacarpal and Phalangeal Fractures

with AO Minifragment Screws and Plates: A Prospective Study. Injury 1993;24:166.

U, McCollam SM, Oppikofer C. Comminuted Fractures of the Basilar Joint

of the Thumb: Combined Treatment by External Fixation, Limited Internal

Fixation, and Bone Grafting. J Hand Surg 1991;16A:556.

KO, Moberg E. Open Reduction and Osteosynthesis of the So-called

Bennett’s Fracture in the Carpometacarpal Joint of the Thumb. Acta Orthop Scand 1953;22:249.

TL, Noellart RC, Belsole RJ. Treatment of Unstable Metacarpal and

Phalangeal Fractures with Tension Band Wiring Techniques. Clin Orthop 1987;214:78.

H II, Carroll C IV. Treatment of Closed Articular Fractures of the

Metacarpophalangeal and Proximal Interphalangeal Joints. Hand Clin 1988;4:503.

H. Ninomiya S, Okutsu I, Tarui T. Dynamic External Finger Fixator for

Fracture Dislocation of the Proximal Interphalangeal Joint. J Hand Surg 1993;18A:160.

DW, Abernathy PA, Raine PA. Unstable Fractures of the Metacarpals: A

Method of Treatment by Transverse Wired Fixation to Intact Metacarpals.

Hand 1973;5:43.

P, Rigault M, Charissoux JL, et al. Recent Fractures of the Base of the

First Metacarpal: Study of a Series of 138 Cases. Ann Chir Main 1994;13:122.