Evaluation of Soft Tissue Tumors

– Evaluation and Management of Musculoskeletal Oncology Problems > 2

– Evaluation of Soft Tissue Tumors

and management. The vast majority of soft tissue tumors are benign,

with benign tumors outnumbering malignant tumors by a factor of at

least 100. This chapter deals with the general diagnostic and

management guidelines for both benign and malignant soft tissue tumors.

More specific information is available in each tumor-specific chapter.

unknown. Environmental exposures, radiation, viral infection, and

genetic associations have all been implicated, though the developmental

associations are casual in most instances (Box 2-1).

-

Benign

-

True incidence is poorly reported

-

~300/100,000

-

-

Outnumber malignant soft tissue sarcomas by 100:1

-

-

Malignant

-

~8,700 cases/year in the U.S.

-

Annual incidence ~1.5/100,000

-

8/100,000 in individuals >80 years old

-

-

Accounts for <1% of all cancers

-

remains ambiguous, the past two decades have provided considerable

insight into the biology of these tumors in the form of cytogenetic and

molecular information. Chromosomal translocations or other chromosomal

aberrations have been reported for virtually every type of soft tissue

tumor. The more consistent genetic findings are outlined in Tables 2-1 and 2-2. In addition, a number of inherited conditions are associated with the development of soft tissue tumors (Table 2-3).

histologically according to the type of tissue they most closely

resemble. The most widely recognized classification is that

of the World Health Organization (WHO), which was first published in 1969 and most recently updated in 2002.

|

Table 2.1 Cytogenetic and Molecular Genetic Alterations Seen in Benign Soft Tissue Tumors

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

-

Adipocytic

-

Fibroblastic

-

Fibrohistiocytic

-

Smooth muscle

-

Perivascular

-

Skeletal muscle

-

Vascular

-

Chondro-osseous

-

Uncertain differentiation

benign, intermediate, and malignant groups. WHO recognizes over 60

subtypes of benign soft tissue tumors and over 50 subtypes of malignant

soft tissue tumors (sarcomas). It is not thought that the malignant

subtypes arise from the benign forms. For example, liposarcoma does not

arise from benign fat in lipoma but rather histologically exhibits

lipoblastic differentiation.

problematic. In contrast, soft tissue sarcomas are exceedingly rare but

diagnostically and therapeutically challenging. Unfortunately both

benign soft tissue tumors and soft tissue sarcomas have a deceptively

similar presentation, and as such a delay in the diagnosis of soft

tissue sarcoma is not uncommon (Table 2-4). While clinical and imaging features will help guide an appropriate work-up, any suspicious soft tissue mass must be biopsied.

|

Table 2.2 Cytogenetic and Molecular Genetic Alterations Seen in Malignant Soft Tissue Tumors

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table 2.3 Inherited Syndromes Associated with Soft Tissue Tumors

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

-

How long has the mass been present?

-

Masses present for long periods of time are most likely benign.

-

New masses arising over a short period of time raise malignancy suspicion.

-

Synovial sarcoma and clear cell sarcoma are classic exceptions (may be present for many years).

-

Any mass that persists for >4 weeks in the absence of clear-cut trauma warrants consideration of biopsy.Table 2.4 Guidelines for the Clinical Presentation of Extremity Soft Tissue Masses

Parameter Benign Malignant Comments Pain Rare* Rare Uncommon in the absence of nerve or bone invasion Size <5 cm >5 cm Location Superficial (subcutaneous) Deep to fascia 1/3 of soft tissue sarcomas are superficial. Mobility Mobile** Fixed Consistency Soft Firm Growth Stable Enlarging Synovial sarcoma and clear cell sarcoma can be very slow-growing. * One benign soft tissue mass that typically presents with pain is an intramuscular hemangioma.

** Benign peripheral

nerve sheath tumors are tethered to the nerve and therefore are mobile

only medially and laterally but not proximally/distally.

-

-

Is the mass enlarging?

-

Enlarging masses indicate an active process.

-

Patients often have difficulty assessing

growth patterns, especially axial lesions (buttock, pelvis, shoulder

girdle); they may not be noticed until of substantial size.

-

-

Is there any history of cancer?

-

Certain malignancies may metastasize to the soft tissues with greater frequency:

-

Lung carcinoma

-

Melanoma

-

Lymphoma

-

-

-

Always measure the size of the mass.

-

Any mass >5 cm warrants biopsy!

-

Any mass that increases in size over time warrants a biopsy!

-

-

Always assess depth.

-

Any deep mass (involving fascia or deeper) warrants consideration of biopsy!

-

-

Determine mobility relative to surrounding structures.

-

Any fixed mass warrants a biopsy!

-

-

Transilluminate superficial masses (rule out ganglion).

-

Palpate for tenderness.

-

Palpate to determine consistency (soft versus firm).

-

Check for pulsations, bruit.

-

Palpate adjacent blood vessels and bones.

-

Perform complete neurological examination.

-

Examine the abdomen for hepatomegaly or splenomegaly.

-

Examine entire extremity; check for satellite lesions.

-

Examine regional lymph nodes.

-

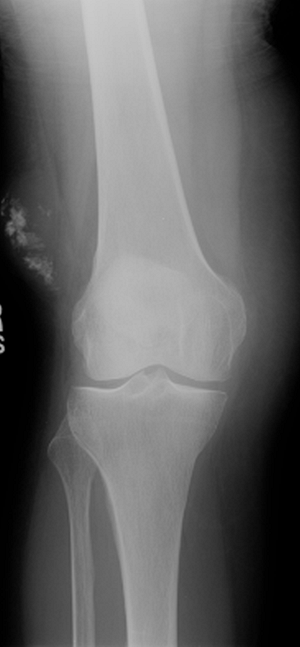

Plain radiographs of the affected area

are important for the evaluation of soft tissue mineralization and bony

involvement. In addition, any patient with a mass suspicious for soft

tissue sarcoma should have a chest x-ray. -

Any soft tissue sarcoma can present with soft tissue calcifications.

-

The most common masses with soft tissue mineralization:

-

Myositis ossificans (more mature mineralization around periphery)

-

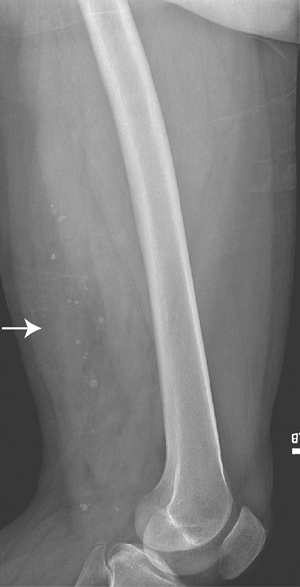

Hemangioma (small, round, well-defined phleboliths; Fig. 2-1)

-

Synovial sarcoma (variable pattern of mineralization)

-

Well-differentiated liposarcoma

-

Extraskeletal chondrosarcoma

-

Extraskeletal osteogenic sarcoma (centrally mature mineralization; Fig. 2-2)

-

-

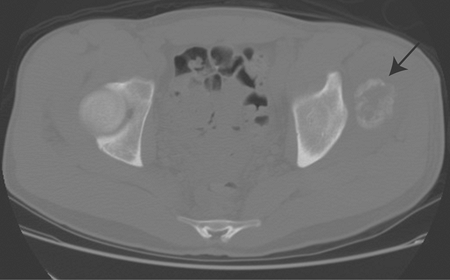

There are four main reasons to obtain a CT scan in patients with soft tissue masses:

-

CT scan of the chest for staging in soft tissue sarcoma

Figure 2-1 Soft tissue phleboliths. Diagnosis: Hemangioma.

Figure 2-1 Soft tissue phleboliths. Diagnosis: Hemangioma.![]() Figure 2-2 Soft tissue mineralization. Diagnosis: Extraskeletal osteogenic sarcoma.P.32

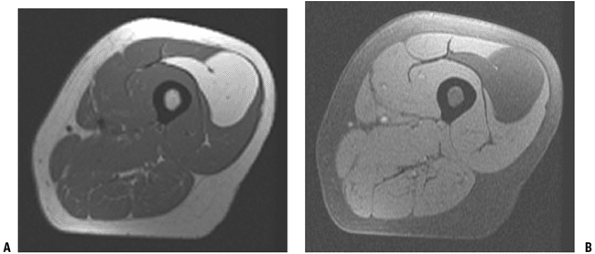

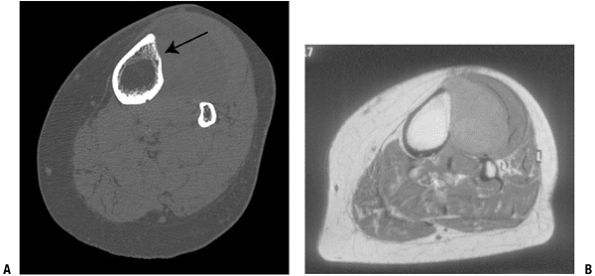

Figure 2-2 Soft tissue mineralization. Diagnosis: Extraskeletal osteogenic sarcoma.P.32 Figure 2-3

Figure 2-3

MRI versus CT scan in the evaluation of adjacent bone involvement in a

patient with soft tissue sarcoma in the leg. The CT scan (A) clearly shows loss of cortex, whereas the MRI (B) is more ambiguous. -

Evaluation of underlying bony involvement (Fig. 2-3)

-

Evaluation of the primary tumor in patients with contraindication to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

-

Evaluation of pattern of mineralization (Fig. 2-4)

-

-

MRI is the imaging modality of choice in

the diagnosis and therapeutic planning of soft tissue tumors. It is

superior to other imaging modalities in determining size, location, and

anatomic relationships to neurovascular structures in multiple planes. -

For soft tissue sarcomas, MRI is useful

for evaluating preoperative radiation or chemotherapy responses and for

detecting local recurrences. -

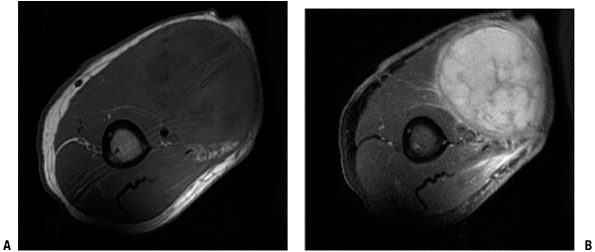

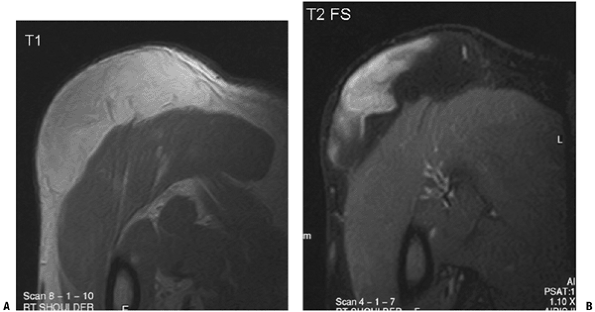

In general, most tumors demonstrate dark signal on T1-weighted images and bright signal on T2-weighted images (Fig. 2-5).

![]() Figure 2-4

Figure 2-4

Mineralized soft tissue mass in the pelvis. CT scan nicely demonstrates

a zonal pattern of ossification with more mature mineralization

peripherally, consistent with myositis ossificans.-

Tumors that do not follow this usual signaling pattern have a narrow differential (Table 2-5).

-

-

MRI alone cannot differentiate benign tumors from malignant ones. Lipomas and synovial cysts/ganglions are exceptions.

-

Lipomas have a characteristic appearance

on MRI, with uniform homogenous fatty signal on all sequences and loss

of signal on the fat-suppression sequences (Fig. 2-6). -

Cysts have homogenous fluid signal with only peripheral enhancement.

-

-

Helpful hints when evaluating soft tissue masses on MRI:

-

Any deep heterogeneous mass or any heterogeneous mass >5 cm regardless of location is a soft tissue sarcoma until proven otherwise.

-

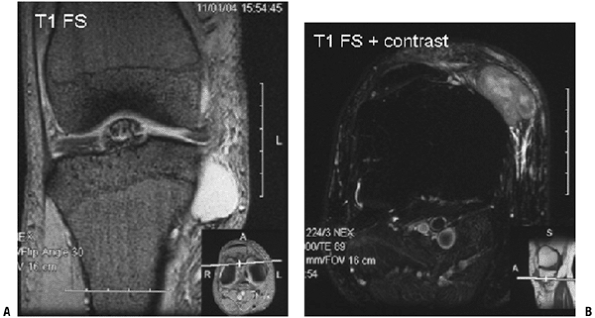

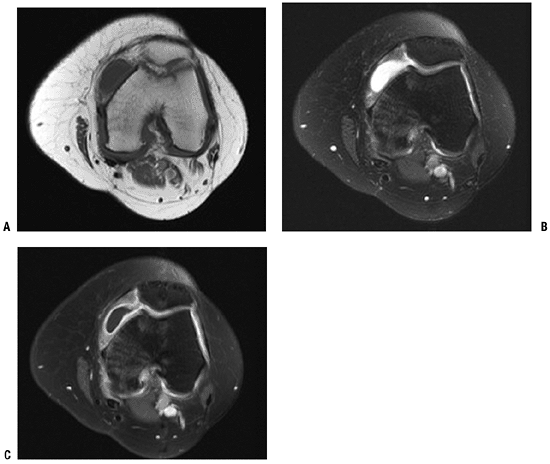

Cysts do not demonstrate central enhancement with gadolinium (Fig. 2-7).

-

Not all small masses near a joint

(especially the knee and wrist) are ganglions. Unfortunately, small

soft tissue sarcomas can occur in and around joints. When in doubt,

obtain an MRI with contrast to differentiate cystic masses from solid

masses (Fig. 2-8). -

Just because some of the tissue has the

same signal as fat does not make it a lipoma. True lipomas are

homogenous on all sequences, are isointense with the subcutaneous fat

on all sequences, and uniformly suppress with fat suppression (see Fig. 2-6).

Well-differentiated to moderately differentiated liposarcomas have

areas of signal consistent with normal fat but admixed with nonfatty

signal (Fig. 2-9).

-

clinicians in outlining treatment strategies for a given patient.

Staging systems guide the diagnostic work-up, the type of local

control, the need for adjuvant treatments, and a long-term follow-up

strategy.

|

|

Figure 2-5 A typical MRI appearance of a soft tissue sarcoma in the arm. (A) The mass displays dark signal on the T1-weighted image, which is isointense with the adjacent muscle. (B)

On the T2-weighted image, the mass displays bright signal relative to the surrounding normal tissues. On both sequences, there is considerable heterogeneity, which is more obvious on the T2 image. |

-

All patients with suspicious soft tissue

masses require MRI and biopsy. (The importance of biopsy choice and

technique is discussed in Chapter 3.) -

All patients with suspected sarcoma require MRI, chest x-ray, CT scan of the chest, and biopsy.

-

Staging systems for benign soft tissue tumors are not well developed or widely used.

-

Most benign tumors have limited local

recurrence potential and distant metastases are exceedingly rare. As

such, evaluations of the extent of disease are unnecessary, and when

surgery is necessary, local excision alone is usually curative.

|

Table 2.5 Tumors Other Than Those with Low T1/high T2* That Have Specific Mri Signaling Characteristics

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||

-

In 2002, WHO subdivided intermediate

tumors into two categories: intermediate–locally aggressive and

intermediate–rarely metastasizing. -

Intermediate–locally aggressive tumors tend to cause local problems and recur locally.

-

Examples include desmoid tumors and atypical lipomatous tumors.

-

Histologically, they demonstrate an infiltrative pattern.

-

Often, wide surgical excision is

necessary, particularly with desmoid tumors, although on occasion even

this is inadequate to achieve local control.

-

-

Intermediate–rarely metastasizing tumors

can also display locally aggressive characteristics but demonstrate the

ability to give rise to distant disease, though to a lesser degree than

fully malignant tumors (on the order of ~2%).-

Examples of such tumors are hemangiopericytoma and giant cell tumor of soft tissues.

-

-

Staging systems for soft tissue sarcomas

rely on histologic grade, size of the tumor, anatomic location of the

tumor, and the degree of regional and distant disease. -

The primary staging system used for soft tissue sarcomas was developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) (Table 2-6).

-

The histologic grading is a complex endeavor that has evolved through the years.P.34

![]() Figure 2-6 Intramuscular lipoma. (A) On the T1-weighted image, the intramuscular mass is the same signal as the subcutaneous fat. (B)

Figure 2-6 Intramuscular lipoma. (A) On the T1-weighted image, the intramuscular mass is the same signal as the subcutaneous fat. (B)

On the fat-suppression T2 image, the mass remains homogenous with a

uniform loss of signal. Post-contrast enhanced images would not show

any enhancement.-

Grading incorporates the mitotic index

(number of mitoses per high-power field), extent of spontaneous

necrosis, and the degree of tumor differentiation, cellularity, and

pleomorphism.

-

-

The anatomic location of the tumor refers

to the location of the tumor relative to the deep fascia and is termed

superficial or deep. -

The size of the tumor has significant prognostic importance.

Figure 2-7 This parameniscal cyst demonstrates homogenous dark signal and bright signal on the T1-weighted (A) and T2-weighted (B and C) images, respectively. (C)

Figure 2-7 This parameniscal cyst demonstrates homogenous dark signal and bright signal on the T1-weighted (A) and T2-weighted (B and C) images, respectively. (C)

With the administration of gadolinium contrast, note the lack of

central enhancement, with enhancement peripherally only. The

enhancement pattern is characteristic for cystic structures.-

For the purposes of the AJCC staging system, tumors >5 cm are deemed large and those <5 cm are deemed small.

![]() Figure 2-8 (A)

Figure 2-8 (A)

This small, well-encapsulated mass near the knee joint demonstrating

homogenous high signal on the T1-weight fat-suppressed image could

easily be mistaken for a cyst. (B)

Contrast administration reveals heterogeneous, central enhancement,

proving this is a solid mass. Biopsy revealed an extraskeletal myxoid

chondrosarcoma. Figure 2-9 (A)

Figure 2-9 (A)

On this T1-weighted image, the subcutaneous soft tissue mass overlying

the deltoid displays areas of high signal with intensity similar to the

adjacent subcutaneous fat. (B) On the

fat-suppression image, while some of the mass displays similar loss of

signal, there are persistent areas of high signal, which indicates the

mass is not simply a lipoma. Diagnosis: Well-differentiated liposarcoma. -

-

The presence or absence of distant metastases carries tremendous prognostic significance.

-

Most distant spread from soft tissue

sarcomas occurs in the lungs, while lymph node, bone, and other organ

involvement is far less common.

-

|

Table 2.6 Ajcc Staging System for Soft Tissue Sarcoma

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

FJ, Khanna JA, McCarthy EF. The role of MR imaging in soft tissue tumor

evaluation: perspective of the orthopedic oncologist and

musculoskeletal pathologist. Magn Reson Imaging Clin North Am 2000;8(4):915–927.

MC, Biermann JS, Montag A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and

charge-savings of outpatient core needle biopsy compared with open

biopsy of musculoskeletal tumors. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1996;78(5):644–649.