REPLANTATION

limbs has been possible for nearly 40 years. The first successful

reattachment of a completely severed human limb was reported by Malt et

al. in Boston in 1962 (55). Komatsu and Tamai (50) have been credited with successful replantation of a completely severed digit in 1965. Zhong-Wei et al. (102)

reported the successful replantation of a severed digit the same year.

Over the past three decades, several microsurgery centers throughout

the world have achieved greater than 80% success rates in replanting

severed digits, hands, and major limbs (6,7,10,14,32,33,34,37,45,47,48,52,57,63,64,68,70,77,82,87,96,99,100 and 101,103,104).

Additional experience, subspecialization in microsurgery with the

increased knowledge and surgical skills in this field, improvements in

microscopes, ultrafine needles, microsuture materials, and other new

and improved instruments have made replantation the procedure of choice

for the management of many amputations (1,4,11,82,88,89).

anastomosis and survival of the replanted or revascularized part is the

technical adequacy of the microvascular repair (82).

Successful microsurgery requires familiarity with the operating

microscope and microsurgical instruments and the careful handling of

small vessels and surrounding tissues. These skills must be learned in

the animal laboratory, not in the clinical operating room. After the

surgeon has demonstrated proficiency in the repair of microvessels and

nerves, in the animal laboratory, then these skills may be transferred

to the operating room. In addition, replantation of amputated parts

should be done by surgeons who are thoroughly trained in surgery of the

upper extremity and hand and who have had sufficient clinical

experience to be able to predict the outcome following replantation of

a severed part.

replant an amputated extremity are the predicted morbidity to the

patient; survival of the replanted part; functional outcome of the

reconstructed limb; and the overall financial burden to the patient,

insurance carrier, or society (83). The

predicted function after replantation should be better than that of a

prosthesis or amputation revision. Because the ultimate functional

result may be unpredictable, the decision of whether to replant an

amputated part is often difficult, even for the experienced

reconstructive surgeon.

process. Based on the experience of more than 1,800 attempted

replantations over a 25-year period by my colleagues and me, we have

developed criteria for proper patient selection. The surgeon must

understand that not only viability but also recovery of useful function

determine success in replantation.

-

Level of amputation

-

Severity of injury (guillotine versus crush or avulsion)

-

Warm and cold ischemia times

-

Age of patient

-

Segmental injuries

-

General health of patient

-

Vocation

-

Predicted rehabilitation

make the decision regarding replantation because they will usually

request replantation even in cases where there is little chance of

survival or function of the replanted part. The final decision must

rest with the surgeon in collaboration with the patient. Social,

ethnic, and religious beliefs about the significance of loss of the

amputated part do influence the surgeon’s decision regarding

replantation, however.

replantation is rigid or absolute, and the criteria, although generally

similar for most replantation surgeons, vary with individual experience

(83). Future experience with replantation and

technological advances in externally powered prostheses are likely to

further alter these criteria. On the basis of this standard, good

candidates for replantation are those with amputations of the following

types:

-

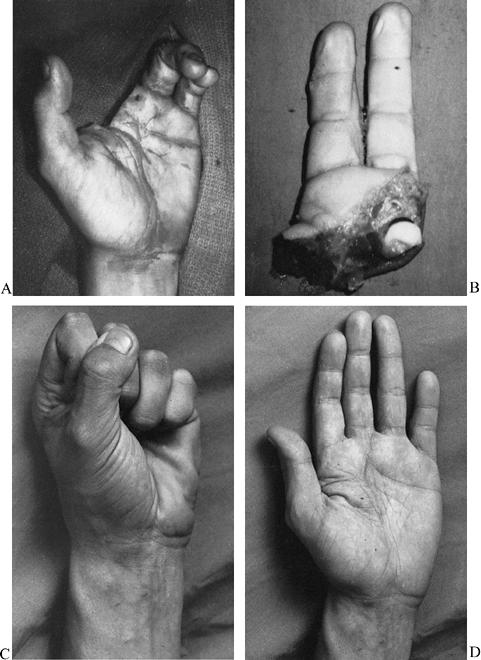

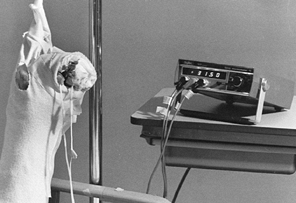

Wrist (Fig. 34.1)

Figure 34.1. Good candidates for replantation include amputations at the level of the wrist. A,B: A complete amputation at the wrist level in a 21-year-old man. C,D: The amount of digital flexion (C) and extension (D)

Figure 34.1. Good candidates for replantation include amputations at the level of the wrist. A,B: A complete amputation at the wrist level in a 21-year-old man. C,D: The amount of digital flexion (C) and extension (D)

seen in this patient 3 years following successful replantation. (From

Porubsky GL, Urbaniak JR. Limb and Digital Replantation. In Flye MW,

ed. Principles of Organ Transplantation. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1989.) -

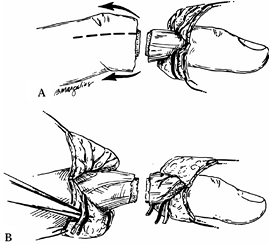

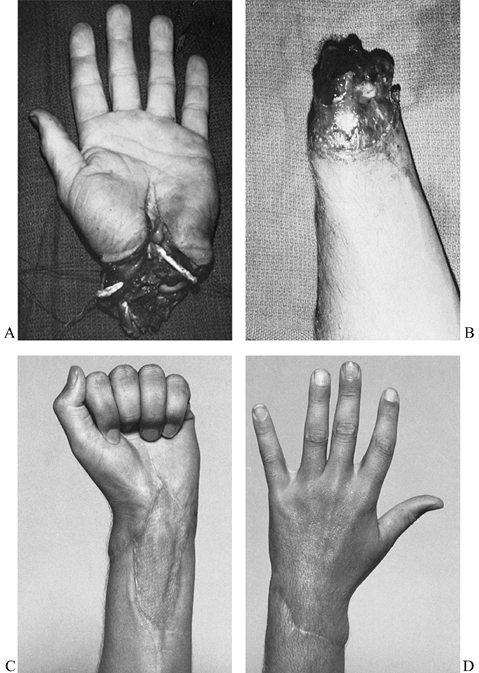

Partial hand (through metacarpal level of palm) (Fig. 34.2)

![]() Figure 34.2. A,B:

Figure 34.2. A,B:

Complete amputation of the left index and long finger through the

metacarpals in a 20-year-old man. The amputated part was reattached as

a composite. C,D: Flexion (C) and extension (D)

1 year later. The patient lacks 5 mm of touching the distal palmar

crease with the index finger and 4 mm with the long finger. He returned

to work as a meatcutter 3.25 months after the injury. -

Thumb (Fig. 34.3)

Figure 34.3. A: Dominant thumb of a 16-year-old boy was avulsed by a nylon rope. B,C:

Figure 34.3. A: Dominant thumb of a 16-year-old boy was avulsed by a nylon rope. B,C:

Replantation resulted in less than 5 mm of two-point sensory

discrimination and individual interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal

flexion and extension. (From Urbaniak JR. Replantation of Amputated Hands and Digits. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Instructional Course Lectures, Vol. 27. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1978.) -

Multiple digits

-

Forearm

-

Almost any body part of a child

-

Elbow and above elbow (only sharply severed or moderately avulsed)

-

Individual digit distal to the flexor superficialis insertion

for replantation, if all other factors are favorable one should attempt

replantation of these amputated parts.

Usually, amputations proximal to the midforearm level are of a crushing

or avulsing nature, which produces considerable muscle trauma.

Myonecrosis and subsequent infection are common problems with this type

of replantation, particularly at the elbow or brachial level;

therefore, be extremely selective in choosing replantation at these

levels.

patients of all ages. A replanted thumb is far better than any type of

reconstructed thumb to replace one that has been amputated (5,31,58,68,73,95) (Fig. 34.3).

Attempt replantation even as far distal as the nail base if vessels for

revascularization can be located. If the patient is healthy, there is

no upper age limit (33,75).

For example, if the thumb and index finger have been completely

amputated in a crushing injury and the distal thumb has irrepairable

distal vessels, transpose the amputated index finger to the thumb

stump. This alteration

should result in excellent thumb function and cosmetic acceptability.

for replantation. Amputations at or distal to the distal

interphalangeal joint of the fingers or the interphalangeal joint of

the thumb can be successfully replanted if dorsal veins can be located

on the amputated part (21,25,26,36,41,43,54,59,75,81,91,98).

As a general rule, at least 4 mm of dorsal skin proximal to the base of

the nail plate must be present for locating veins suitable for repair.

insertion; an excellent functional result can be achieved, and the

operating time is not long (usually less than 4 h) (33,87).

Replantations at this level are usually successful (greater than 90%

viability rate), provide a good appearance, are not painful, allow good

function, eliminate the potential for painful neuromas, and permit an

early return to work (usually less than 3 months) (16,33,87).

body part because, if the reattached part survives, useful function can

be predicted (20,84).

neither are contraindications. Injuries generally not considered ideal

for replantation include:

-

Amputations in patients with other serious injuries or diseases

-

Amputations at multiple or segmental levels

-

Severely crushed or avulsed parts

-

Amputations in which the vessels demonstrate arteriosclerosis

-

Amputations in mentally unstable patients

-

Amputations with prolonged warm ischemia time (more than 6 h)

-

Individual finger amputations in the

adult at a level proximal to the superficialis insertion (proximal

interphalangeal joint or proximal)

however, there are no methods for replacing the most distal vessels in

the amputated part. Because arteriosclerotic plaques on the intima

often preclude functional patency following the reanastomosis of small

vessels, the arteries of older patients must be thoroughly evaluated

under the microscope before reattachment. In addition, patients with

diabetes mellitus may have diseased blood vessels, which would lessen

the likelihood that repaired vessels will remain patent. Again, the

experienced microsurgeon can determine the potential success of an

anastomosis by studying the vessel structure under a high-powered

microscope.

phalanges and midpalm or at the elbow and above the elbow, in the same

patient), replantation is usually not recommended because the time

commitment is large and the predicted outcome is uncertain (8).

decision regarding replantation. Mental instability is not uncommon in

patients who sustain completely amputated upper extremities, but it is

often difficult to determine the patient’s mental stability during the

limited preoperative assessment stage.

recommend not replanting the isolated finger amputation proximal to the

flexor superficialis tendon insertion. Although the cosmetic result is

excellent, the overall function of the hand is usually not improved; in

fact, this digit sometimes gets in the way. Special considerations,

such as for musicians, young women, and children, do influence

selection, however (72,87).

The patient with a replanted index finger that was amputated at the

base will usually bypass the replanted digit to oppose the thumb to the

long finger.

chances of viability, length of surgery and hospitalization,

anticipated functional outcome, predicted loss of time from work, and

cost compared with an amputation revision. Equipped with all of this

information, most patients and families will insist on replantation;

therefore, the ultimate decision rests with the surgeon. On many

occasions the final decision cannot be made until the vessels of the

amputated part are carefully evaluated under the operating microscope.

essential to achieve success in replantation. Generally, if the warm

ischemia time of the amputated part exceeds 6 h, do not attempt

replantation. If the amputated part contains muscle, the ischemia time

is much more critical. Muscle is extremely sensitive to ischemia,

compared with tissues such as skin, bone, and tendon (22,23).

and bacterial growth. All amputated parts should be cooled during the

transportation to a replantation center. If the part is cooled,

successful replantation is possible with cold ischemia times up to 12

h, or even longer if it is a digit; we have successfully replanted

amputated digits with cold ischemia times up to 30 h. However,

transportation of the amputated part and the patient should be as rapid

as possible.

-

Wrap the part with gauze moistened with

Ringer’s lactate or saline solution and place it in a plastic bag,

which is then placed on ice. -

Alternatively, immerse the part in Ringer’s lactate or saline solution in a plastic bag and place this bag on ice.

-

The part is less likely to become frozen (frostbitten).

-

The part is less likely to be strangled by the wrappings.

-

Instructions are easier to explain to the primary-care physician.

-

Maceration secondary to immersion is not a problem.

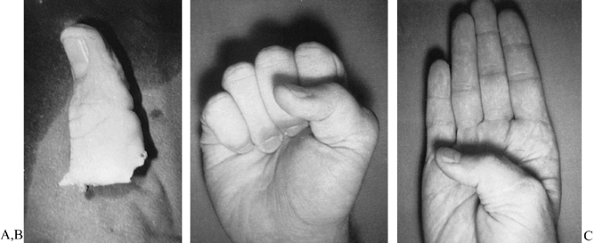

so only the equipment essential for replantation surgery is mentioned

here. A great variety of expensive microsurgery instruments are

unnecessary; the appropriate instruments must be available, however,

and the working ends must be well maintained for precision handling of

the small microstructures, fine needles, and suture material (Fig. 34.4) (11,83,88). Basic replantation surgery instruments include the following:

|

|

Figure 34.4. Basic microsurgery instruments for replantation. Left to right, bottom row:

Micro-Pots (angled) scissors, spring-loaded curved tipped microscissors, spring-loaded needle holder, two jeweler’s forceps, 30-gauge blunt needle syringe for irrigation. Top row: Lacrimal duct dilator (below), latex background material (above), microclip approximator (below), Van Beek nerve approximator (above), and small cotton absorbent sponge sticks. |

-

Surgical loupes

of 3.5× to 4.5× are necessary for the initial debridement, exploration,

and dissection of the amputated part and injured extremity. -

An operating microscope

with magnification to at least 20× is essential. Preferably, the

operating microscope should have a beam splitter and a double head that

allows the surgeon and the first assistant to visualize the same

microfield. Foot controls for focusing, zoom magnification, and

horizontal xy movement are ideal. We use the microscope for the repair of any vessels distal to the axilla. -

Microinstruments

should be at least 10 cm long to allow the handles to rest comfortably

in the thumb–index webspace. Instrument handles at least 15 cm long are

recommended for all microsurgery instruments to increase the

versatility of the instruments when operating in deep fields.

-

A spring-loaded needle holder and spring-loaded microscissors

-

Two sets of jeweler’s forceps

-

A microtipped dilator (lacrimal duct dilator)

-

A microirrigator (30-gauge smooth-tipped needle)

-

Various-sizes of (approximator) microclips mounted on some type of bar

disposable type with two plastic tips mounted on a metal sliding bar.

The use of a new clip or microapproximator for each procedure better

assures a constant pressure of less than 30 g/cm. Other helpful

equipment includes:

-

Small hemoclips to tag the vessels and nerves and to use when isolating or harvesting vessels

-

A small-tipped bipolar cautery, essential in isolating and mobilizing the vascular structures to be repaired.

is useful in highlighting the vessels and suture material. I prefer a

yellow background material, particularly if the lighting is low.

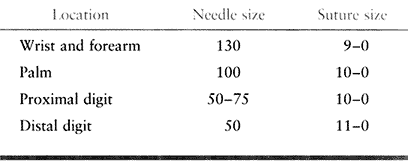

suggests the appropriate needle and suture size for amputations at the

wrist level or distal. An 8-0 or even 7-0 suture may be used proximal

to the elbow.

|

|

Table 34.1. Needle and Suture Sizes for Wrist Amputation

|

with bupivacaine, a long-acting local anesthetic. Regional anesthesia

is favored because of the peripheral autonomic block, which increases

vasodilation and peripheral blood flow (25).

Some inhalation anesthetics may result in vasospasm and diminished

peripheral blood flow. General anesthesia is necessary in the

uncooperative patient or for children 12 years old or younger. Keep the

operating room warm at all times to diminish peripheral vasospasm

caused by cooling of the body temperature.

into two subteams (here designated teams A and B) when the patient and

the amputated part arrive in the emergency room. This practice is more

critical with major limb replantations. Surgeons without microsurgical

experience may help prepare the amputated part and patient; however,

they must be experienced in dissecting the small vessels lest

irreparable damage may occur. They may, however, be quite helpful in

the bone trimming, bone fixation, and tendon repair and subsequent

wound coverage.

-

Immediately transport the amputated part

to the operating room for initial cleansing with Hibiclens and sterile

Ringer’s lactate solution. -

Place the prepared amputated part on a

bed of ice covered with a sterile plastic drape. If multiple digits are

involved, these may be cooled by storage in a refrigerator or under ice

packets until the appropriate time for replantation. Care must be taken

not to freeze them. -

Under the operating microscope or with operating loupes (depending on the size of the amputated part),

P.1152

carefully debride the part or parts and identify and tag the nerves and

vessels with small hemoclips. This identification and tagging of the

neurovascular structures will save time when microsurgeons have to work

in a bloody field at a later time. The ease in locating the tagged

structures, particularly in multiple amputations, is definitely

beneficial in the later stages of replantation, particularly if the

procedure is lengthy and fatiguing. -

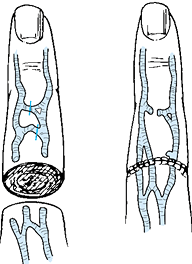

Make bilateral longitudinal midlateral

incisions, which provide the most rapid and best exposure of the

neurovascular structures on the digits (Fig. 34.5).

Place the incisions slightly toward the dorsum so that both the dorsal

and palmar skin flaps can be reflected to locate the veins, nerves, and

arteries with ease.![]() Figure 34.5. A: Bilateral longitudinal midlateral incisions. B:

Figure 34.5. A: Bilateral longitudinal midlateral incisions. B:

Neurovascular bundles exposed palmarly and veins exposed dorsally.

(From Urbaniak JR. Replantation in Children. In Serafin D, Georgiade

NG, eds. Pediatric Plastic Surgery. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1984:1168.) -

Using magnification, isolate the digital nerves and vessels for a distance of 1.5 to 2 cm and tag them.

-

Identify the dorsal veins on the

amputated part by reflecting the entire dorsal flap of skin and

dissecting the subdermal tissue. In the amputated digit, locating and

labeling the veins may be delayed until after arterial anastomosis,

which makes identification of veins easier because of the backbleeding,

particularly if the patient and amputation stump are ready to receive

the amputated part. If the patient is not yet prepared to receive the

amputated part, however, then search for the veins at this time to

reduce the overall operating time. -

Continue additional debridement after isolation and labeling of the neurovascular bundles.

-

Shorten and trim the bone appropriately on the amputated digit.

-

Insert an intramedullary Kirschner wire

retrograde in the amputated part so the part is prepared for immediate

reattachment. If the bone is closely surrounded by soft-tissue

structures, a 16-gauge hypodermic needle serves as an excellent

protector guide for the 0.45 Kirschner wire.

-

Thoroughly evaluate the patient in the

emergency room with a physical examination, radiographs of the chest

and injured extremity, cardiogram, complete blood count, blood

chemistries, urinalysis, blood type and cross-match, and activated

partial thromboplastin time. -

Begin intravenous fluids and administer

intravenous antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis if indicated. Insert an

indwelling urethral catheter if a long procedure is anticipated. -

Using magnification and tourniquet

ischemia, debride the stump and locate and label the neurovascular

structures in a manner similar to the preparation used by Team A on the

amputated part. -

It may be difficult to locate the

subcutaneous veins on the stump, particularly for the inexperienced

surgeon. Because successful replantation depends on the patency of an

adequate number of veins, this is a critical point

of the operation. Isolating veins in the digit may be tedious and

requires meticulous dissection and careful handling of these small

structures. After one good vein is located in the subcutaneous layer,

this vein may serve as a guide to direct the surgeon to similar veins

in the same subdermal plane.

replantation will vary slightly depending on the level of amputation

(digit versus levels proximal to the wrist) and type of injury (sharp

versus avulsion). The technique of replanting amputated digits is

described first because these amputations are much more common than the

more proximal amputations. The variations in technique used for major

limb replantations are described subsequently.

|

|

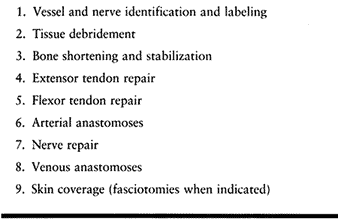

Table 34.2. Order of Repair for Digit and Hand Replantation

|

not, in haste to reestablish blood flow, compromise on the irrigation

and debridement. A thorough wound debridement is essential. A pulsating jet lavage is useful in severely contaminated major limb replantations.

Excise all necrotic and potentially necrotic tissue, particularly muscle.

It is much easier to make repairs at the time of the initial

reconstruction than to reoperate secondarily through the repaired

structures of the replanted part.

Sufficient bone must be resected to ensure the ease of approximation of

normal intima in the vascular anastomosis. Additionally, bone

shortening allows easier skin coverage of the repaired veins,

particularly on the dorsum of the digits. The amount of resected bone

depends on the type of injury. In an avulsion or crushing type of

injury, more bone must be resected until normal intimal coaptation is

possible without tension. For the digit, it is usually necessary to

resect 5 to 10 mm of bone; in amputations proximal to the hand, 2 to 3

cm of bone resection may be indicated. In the avulsion type of injury,

even more bone resection is done. If it appears that a great deal of

bone must be resected in the digit or in partial hand amputations, use vein grafts to make up the deficit in the arteries and veins rather than doing excessive bone shortening.

shortening is seldom necessary, and instead they recommend vein

grafting when there is considerable intimal damage (52).

Bone shortening should usually be chosen over vein grafting, however,

because there is often concomitant damage to the nerves and other soft

tissues. These injured structures can be more easily managed after bone

shortening. However, do not hesitate to perform vein grafts when they

are indicated (for example, when the loss of a potentially functional

joint may result from bone shortening). This is particularly true for a

child, for whom excessive bone resection should be avoided because it

results in the excision or potential damage to the epiphysis and joint.

Do not hesitate to perform interposition vein grafts when they are

necessary; it is quicker, easier, and less

frustrating to perform an interposition graft than to redo a difficult

anastomosis several times, or even one time.

shortening is done on the amputated part to preserve maximal length on

the stump in case replantation fails. This is not always possible, as,

for example, when attempting to preserve joint function. Several

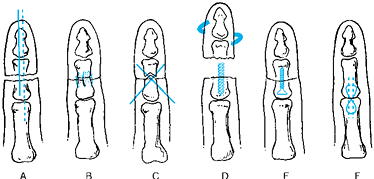

methods of bone fixation are available (Fig. 34.6) (41,79,86,97):

|

|

Figure 34.6. Methods of bone fixation in replantation. A: Longitudinal intramedullary Kirschner wire or wires (an oblique Kirschner wire may be added to prevent rotation). B: Interosseous wiring. C: Crossed Kirschner wires. D: Intramedullary screw or bone peg. E: Miniplates and screws. F: Tension band technique.

|

-

Longitudinal intramedullary Kirschner wire or wires

-

Longitudinal intramedullary Kirschner wire plus oblique Kirschner wire to prevent rotation

-

Crossed Kirschner wires

-

Interosseous wiring

-

Intramedullary screw or bone peg

-

Miniplates and screws

-

Tension band technique.

replantations; however, certain methods may be preferred in specific

areas, such as near the joint or epiphyseal plates. When possible, it

is preferable to perform bone stabilization in a digit with double

axial Kirschner wires because the lowest nonunion and complication

rates occur with this method (97). This is the

easiest and quickest method when a motorized drill is used for careful

pin placement. A large-bore hypodermic needle (16-gauge) is often used

as a guide to prevent the surrounding soft tissue from

wrapping up near the bone ends. In

more than 1,800 replantations, we have experimented with all methods of

bone stabilization and prefer single or double axial Kirschner wire

fixation for the following reasons:

-

Speed and simplicity of the technique

-

Minimal bone exposure required

-

Minimal skeletal mass needed for fixation

-

Ease of reshortening or readjusting the bone approximation if deemed necessary

-

In children, the likelihood of physeal

damage is minimal with a single well-centered intramedullary

longitudinal pin. A second axial intramedullary pin is frequently used

for better stability (29).

the repaired neurovascular bundles, either by contact or by tethering

of the vessels or the protective retaining ligaments. I prefer crossed

Kirschner wires for arthrodesis of joints. A chevron bone cut aids

stabilization when crossed Kirschner wire fixation or the tension

wiring is used.

metacarpal stabilization in replanting a complete amputation at this

level. This method is easy and rapid and provides immediate stability.

Its use is limited in arthrodesis of other joints because some flexion

is usually desired. Immediate fixation allows early motion of the

digits; however, the screw is difficult to remove if the replanted

digit becomes infected. Bone pegs or other intramedullary devices can

be substituted for the screw. Intramedullary devices, however, are not

favored in highly contaminated wounds.

3, 6, and 9 o’clock in each end of the bone. Then place two strands of

24-gauge wire perpendicular to each other. This provides good stability

(86). It is particularly useful for fractures

in the metaphyseal areas or even for primary joint fusions. Immediate

or early motion is usually possible. It does take slightly more time

than intramedullary pins, but the amputated part can be prepared by

having the wires inserted in one end by one of the teams.

nonunion is rarely a significant problem in replantation of digits.

This method requires extensive bone exposure, with the possibility of

further soft-tissue damage, and it also requires more time. In major

limb replantation, however, it is the preferred method because of the

precision and rigid fixation obtained (10,32,61).

experienced hand surgeon, is obtaining proper digital alignment when

replanting multiple digits. This may present a problem even when

replanting a single digit. Check the relationships of the digits

frequently in extension and flexion. Observe the cascade and rotation

of fingertips; in general, when flexed, the fingertip should point to

the scaphoid bone. Most replantations do survive, so take great care to

achieve anatomic alignment and rotation of the replanted parts. In

adults there are occasional indications for primary silicone implant

arthroplasty with replantations at the joint level, such as an effort

to save proximal interphalangeal joint function in a musician. This is

particularly the case if one of the central digits (long or ring

finger) is amputated at the proximal interphalangeal joint level. It is

actually quicker and easier to perform a silicone implant arthroplasty

than a primary fusion; however, the indications are not common. In

addition to bone stabilization, whenever possible try to repair the

periosteum, capsule, and ligamentous structures to provide better

gliding of joints and tendons and to promote joint stability.

tendons primarily, just after bone stabilization. Use surgical loupes

in extensor tendon repair, and keep in mind the following procedures:

-

Using two horizontal mattress sutures of 4-0 polyester or absorbable suture is sufficient.

-

It is important to repair the entire extensor mechanism, which may include repair of the extensor hood or lateral band.

-

In some severe avulsion injuries, if no

extensor tendons are available for repair, I recommend extensor tendon

grafting as a secondary procedure. -

In the digits it is usually advisable to

perform interphalangeal joint arthrodesis because of the difficulty in

reconstructing the extensor mechanism as well as dealing with other

injuries. -

In children, primary extensor tendon grafting is favored over interphalangeal joint fusion (67,78,84,90).

replantations. Secondary repair is rather difficult because of the

excessive scarring around the repaired nerves, vessels, and joints.

Secondary flexor tendon repair in replanted digits usually requires a

two-stage silicone rod procedure in digits other than the thumb.

Because this procedure amounts to two additional surgical procedures,

it is wise to attempt primary repair as follows.

-

Take care not to provoke spasm or damage to the proximal arteries.

-

Try to retrieve the proximal stumps by flexing the wrist, massaging the palm, or extending the other digit.

-

If these methods are unsuccessful, insert

wall suction tubing in the proximal portion of the flexor sheath, turn

on the suction, and withdraw the proximal stump. -

If all of these methods fail, make proximal incisions to locate the tendons (57).

-

Blind grasping with some type of tendon retriever must not be performed because it may produce irreversible damage to the vital proximal vessels.

repair is to relieve any undue compression or tethering of the proximal

vascular tree that could be caused by proximal retraction of the

severed flexor tendons.

-

The type of material best suited for suture repair is 4-0 polyester on a double-armed curved needle.

-

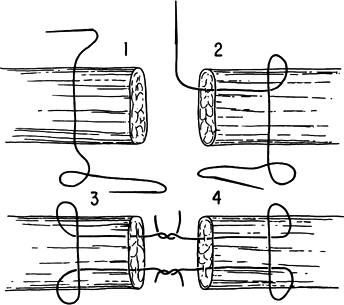

The Tajima suture method is excellent for primary flexor tendon repair in replantation surgery (Fig. 34.7).

Figure 34.7. The Tajima suture method. (From Urbaniak JR. Replantation in Children. In Serafin D, Georgiade NG, eds. Pediatric Plastic Surgery. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1984:1168.)

Figure 34.7. The Tajima suture method. (From Urbaniak JR. Replantation in Children. In Serafin D, Georgiade NG, eds. Pediatric Plastic Surgery. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1984:1168.) -

With the Tajima method, sutures can be

placed in each end of the tendon initially, and the approximation

secured any time during the procedure. -

This delayed coaptation has the advantage

of allowing the digit to be held in full extension for better vascular

and nerve repair, particularly in the area of the proximal phalanx.

digits may require subsequent tenolysis; however, do not do a tenolysis

for at least 3 to 6 months after the primary repair.

be safely performed as long as 3 months after the initial replantation

or revascularization. Usually the two-stage silicone rod method is

indicated.

Anastomose the arteries after bone fixation and extensor and flexor

tendon repair. The recommended number of arteries to repair is as

follows:

-

With the digit, it is advisable to repair both arteries when possible.

-

At the palm or at the wrist level, anastomose all available arteries to increase the chances of survival (56).

Some microsurgeons recommend the repair of only one digital artery to

diminish the operating time; however, we have demonstrated that both

vessels, even in multiple digital amputations, should be anastomosed to

increase the survival rate (52).

-

Free the arteries from their surrounding

connective tissue for a distance of 1.5 to 2 cm. Perform this

dissection under the microscope with microsurgical instruments. Small

branches from the arteries may be safely coagulated with bipolar

cautery. -

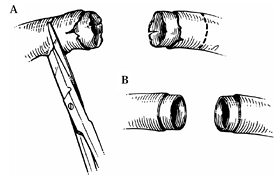

Dissect a severed artery until normal intima is visualized under high-power magnification. Only normal intima must be reconnected (Fig. 34.8).

![]() Figure 34.8. Preparation of the vessel. A: The damaged portion must be resected until normal intima is visualized under high-power magnification. B: Minimal adventitia is stripped to make the lumen clearly visible.

Figure 34.8. Preparation of the vessel. A: The damaged portion must be resected until normal intima is visualized under high-power magnification. B: Minimal adventitia is stripped to make the lumen clearly visible. -

The two most

critical factors in achieving successful microvascular anastomosis are

the surgeon’s skill and expertise and the ease of coaptation of normal

intima to normal intima with minimal tension. -

Assess the most distal and proximal

portions of the exposed vessels to ensure there is no damage to the

media or surrounding adventitia. Such an injury indicates the need for

further arterial resection and vein grafting.

-

After sharply trimming the opened end of

the proximal stump and enlarging it with jeweler’s forceps or a

dilator, an excellent pulsating blood flow must occur. -

Active spurting blood in a digital vessel should produce a persistent stream of at least 5 cm for about 20 to 30 seconds.

-

Do not use this vessel for repair.

-

Take steps to relieve the proximal vasospasm that is present.

-

Be certain that the patient is not

hypotensive, hypovolemic, cold, acidotic, or in pain, because all these

factors introduce unwanted vasospasm. -

Perform thorough irrigation of the proximal lumen with warm heparinized Ringer’s lactate solution to relieve vasospasm.

-

If it is certain that no proximal

mechanical block exists, place papaverine in a 1:20 solution with

normal saline directly on the proximal vessel or gently insert it into

the lumen with a blunt needle. This maneuver usually provides an

excellent pulsatile flow that lasts for at least 30 min. -

Exercise caution when using papaverine or

similar dilating agents because the flow induced may be temporary and

flow may be induced in vessels with damaged intima.

-

Insert the two vessel stumps into the approximating microclip. Coapt the ends without tension.

-

If undue tension is present, use an interpositional vein graft obtained from the palmar forearm.

-

Trim the vessel ends with sharp straight scissors so that no adventitia covers the ends of the lumen.

-

Carefully dilate the lumen of each end with jeweler’s forceps or a lacrimal duct dilator.

-

Irrigate the lumen with heparinized Ringer’s lactate solution and reinspect the intima for complete normalcy.

-

Just before beginning the anastomosis,

give an intravenous bolus of 3,000 to 5,000 U of heparin (decrease this

dose in young children).

-

Apply two stay sutures of 10-0

monofilament nylon 180° apart. Do not tie the sutures too tightly

because this will produce necrosis of the vessel wall. -

The distance from the needle insertion to

the cut end of the vessel should be about one or two times the

thickness of the arterial wall. -

Do not pinch or touch the intima with the jeweler’s forceps.

-

After the application of each knot,

carefully irrigate the anastomosis site with heparinized Ringer’s

lactate and examine it to ensure the suture does not pierce the back

wall. -

After the anterior wall is repaired, turn

over the clip approximator and again examine the lumen under

high-powered magnification to ensure that all sutures are properly

placed. -

Place additional sutures in the back wall in a similar manner.

-

Usually six to nine sutures are required to repair an artery 1 mm in diameter.

-

In the small distal vessels, particularly in children, sometimes only four or five sutures are necessary for the anastomosis.

arterial anastomosis, the fingertip will begin to turn pink if there is

adequate perfusion. Capillary refill should be excellent, and pulp

turgor good. If the amputated part has been without blood flow for

several hours and has been cooled for a prolonged period, a return of

adequate perfusion to the distal part will be delayed. Under these

circumstances, proceed with repair of the digital nerve and the

opposite digital artery. In addition to warming the replanted part,

this waiting period is often all that is necessary to achieve adequate

distal perfusion.

safely for each vascular anastomosis. The tourniquet is helpful in

diminishing blood loss as well as decreasing operating time. If the

microsurgery is skillfully and rapidly performed, the patency rate will

not be affected by the ischemia.

anastomosis to ensure that the anastomosis is patent and blood flow is

strong. The tourniquet may be inflated or deflated many times during

the procedure for nerve, artery, and vein repair.

-

Because all available microclips produce some degree of vessel wall damage, do not apply them for more than 30 min (72).

-

In a crushing or avulsion injury, and if

the procedure is lengthy, consider giving serial doses of heparin (500

to 1,000 U every hour) intravenously. Adjust this dosage for children. -

After completion of the anastomosis, release the microclips; the blood flow across the anastomosis site should be immediate.

may be shifted. For example, in a ring-finger avulsion, the proximal

ulnar digital artery may be shifted to the distal radial digital artery

if these ends are less traumatized. In most instances, however, a vein

graft is used if the distal artery is salvageable (85).

-

For replantation of thumbs that have been

avulsed or amputated, I prefer to use an interpositional vein graft

from the ulnar digital artery of the amputated thumb to the first

dorsal metacarpal artery, or to the dorsum of the hand, for an

end-to-side anastomosis into the radial artery at the wrist. For

expediency, the reversed vein graft is often anastomosed to the ulnar

digital artery of the detached thumb before bone fixation (13). -

The final stage is the connection of the

proximal end of the vein graft into the artery. We use interpositional

vein grafts in about 20% of our replantations to obtain reapproximation

of healthy arteries and veins. The palmar aspect of the wrist contains

veins 1 to 2 mm in diameter that are appropriate for replantation of

digits. -

Hint: If the use of vein grafts is

anticipated, harvest the vein grafts from the forearm in the initial

steps of replantation, using loupe magnification before bringing in the

operating microscope, in an effort to save time.

It may be necessary to mobilize or harvest veins to achieve this ratio (Fig. 34.9). Perhaps the greatest error in venous anastomosis is trying to repair veins under tension. If vein harvesting does not allow coaptation without undue tension, then vein grafts must be used. Following this principle will elevate the patency rate and diminish the surgeon’s frustration as well.

|

|

Figure 34.9.

The mobilization or harvesting of veins is a useful method of achieving ease of approximation for vein reconstruction in a completely amputated digit. An attempt is made to repair two veins for each artery. |

-

The technique of vein repair is similar to that for arterial repair with only a few exceptions.

-

Generally fewer sutures are necessary at

the anastomosis site because the blood flow through the venous system

is not as strong as through the arterial system. -

Because the walls of the veins are more fragile than those of the arteries, minimize the application time of microclips.

-

The distance from the needle insertion to the cut in the vessel should be two to three times the thickness of the wall.

-

Use constant irrigation of the suture line with warm heparinized lactate solution to float the thin walls apart.

-

Do not waste time repairing the very

small veins; instead, connect only the largest veins. One large

repaired vein is more reliable than two smaller repaired veins.

impossible to locate a suitable dorsal vein. Various available options

are as follows:

-

Arteriovenous shunt.

If successful flow through a repaired digital artery is established,

retrograde flow from the unrepaired distal contralateral artery may be

seen. In the absence of a suitable vein in the distal part, connect

this digital artery to a proximal vein (arteriovenous shunt). This

procedure is successful in about half of the attempted cases in

providing sufficient venous drainage (76,93). -

Removal of the nail plate.

Removing the nail plate allows venous oozing from the nail bed. Every 1

or 2 h, have a physician, nurse, or family member stroke the nail bed

with a cotton-tipped applicator to stimulate bleeding from the nail

bed. In the interim, apply heparin-soaked pledgets to the exposed nail

matrix. -

Surgical leeches.

Surgical leeches have been successfully used when venous congestion is

apparent. Place the leeches, which are readily available from various

biological

P.1158

companies,

on the failing part until they become engorged with blood; remove them

and replace with fresh leeches every few hours (12,51). -

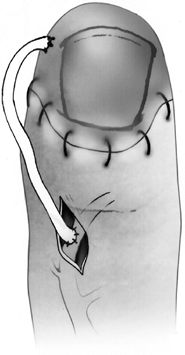

Venocutaneous fistula. The venocutaneous fistula technique involves the construction of a temporary venous return bypass using a venous graft (46).

Anastomose the proximal side of the venous graft to a vein at the

dorsum of the stump. Then suture the distal end of the graft to the

skin around a punch wound on the volar side of the replanted fingertip (Fig. 34.10).![]() Figure 34.10.

Figure 34.10.

The venous cutaneous fistula, a technique for reducing venous

congestion in replanted fingertips when distal dorsal veins are not

present. A cut is made in the volar pulp, and the vein graft extends

from this bleeding fistula to an easily located dorsal vein on the

proximal stump. (Modified from Kamai K, Sinokawa Y, Kishibe M. The

Venocutaneous Fistula: A New Technique for Reducing Venous Congestion

in Replantation Fingertips. Plast Reconstruct Surg 99:171;1997.) -

Periodic massage.

Periodic massaging of the distal segment to enhance venous drainage

improves the venous outflow temporarily but is usually not successful

in achieving viability of the part if it must be continued more than a

day or two. -

Skin grafts.

When there is an absence of skin on the dorsum of the replanted digit,

cover the anastomosed veins with a split-thickness or full-thickness

graft. -

Venous flaps. If there is a deficit of veins in addition to subcutaneous tissue and skin, cover the defect by a venous flap (27,42,60,80).

This flap may be based on a proximal pedicle from an adjacent digit or

freely harvested from the dorsum of the hand or foot or volar forearm.

A vein graft with its covering of subcutaneous tissue and skin serves

as a conduit for venous return as well as skin coverage.

arteries to decrease blood loss and maintain a bloodless field for

better vision (57,58).

By judicious use of the tourniquet, however, the artery may be repaired

first and a dry field maintained. This sequence provides the advantage

of earlier revascularization and allows easier location of the most

functional veins, detected by their spurting backflow. Additionally, if

the veins are repaired first, and a subsequent arterial anastomosis

fails to show adequate arterial inflow, the surgeon has wasted valuable

time on a nonsalvageable part.

interphalangeal joint or deep in the thumb–index webspace, the back

wall inside-out technique is favored over the conventional two-stage

microanastomosis (1). Use this method in cases

where limited exposure of the vessel ends may preclude the possibility

of inverting the vessel for back wall repair.

outside in, withdraw it, and pass it from inside out on the other

vessel. Begin the repair with the back wall and, by alternating

sutures, work the knots toward the front wall.

is sutured to the digital artery of the amputated fingertip before bone

fixation. This sequence allows for better exposure and an easier

anastomosis (40).

cements have been developed for small vessel repair, but none has

proven as successful as interrupted suture methods (44,53,72).

because the bone has been shortened, and no tension should be present

at the suture line.

-

Attempt primary repair in all replantations, when feasible.

-

If direct end-to-end repair is impossible, then use primary nerve grafts.

-

The median antebrachial cutaneous nerve of the ipsilateral extremity is ideal for primary nerve grafting in the digital nerve (62).

-

The nerves from a discarded segment such as a severely damaged digit may be used to bridge the gap.

-

The Van Beek nerve approximator (Fig. 34.4) is extremely helpful in repair of nerves in difficult areas.

-

Cut the nerve ends sharply until pouting fascicles are seen on each stump.

-

Align the fascicles on the freshly cut

nerve ends and approximate the ends without undue tension, using 8-0 to

10-0 monofilament nylon or polypropylene (prolene). -

Epineural repair after obtaining geographic fascicular alignment is the best method for the digital nerves.

-

Only two or three epineural sutures are necessary; more sutures are used in proximal injuries, where the nerve is larger.

-

Fibrin glue may be helpful but really does not save time in replantation (44).

-

Loosely approximate the skin with a few

interrupted nylon sutures. Usually the midlateral incisions are not

closed to allow for decompression of the digital vessels. Excise all

potentially necrotic skin, and place no tension on the skin during the

closure. Cover the vessels without constriction from the overlying skin

or sutures. A local flap or split-thickness graft may be necessary,

even for digital vessel coverage. Large defects may be covered by

“flow-through” arterialized venous flaps or pedicled venous flaps (27,42,60,80). Fasciotomies are indicated if the slightest pressure or constriction occurs. -

Cover the wounds with small strips of gauze impregnated with petrolatum or antibacterial grease. Never place these strips in a continuous or circumferential manner around the replanted part.

Although it is preferable not to cover the replanted part with any

dressing or splint, to allow free drainage and early active motion,

this is usually not feasible because some type of protective dressing

is necessary. The ideal dressing is bulky and uniformly compressive but

not constrictive. -

Extend the plaster splints above the elbow to prevent proximal slippage while the hand is being elevated (Fig. 34.11).

Apply plaster splints on one side of the hand (usually on the palmar

aspect) so that the dorsum of the hand can be inspected if there is a

postoperative problem. If flexor tendons have been repaired, however,

place the splints dorsally to prevent unwanted pull of the flexors

against the rigid plaster. Figure 34.11.

Figure 34.11.

Digital temperature is monitored with a telethermometer and small

surface probes. These quantitative skin temperature measurements have

proven to be the most reliable indicators of replantation status. -

Then elevate the extremity in the bulky

compressive dressing by a soft (Styrofoam) cradle boot. Keep the

fingertips exposed for application of temperature probes and frequent

clinical observation. The environment of the bulky compressive dressing

seems to be well suited to the replanted part: often, blood flow

increases to the fingertips at the conclusion of the dressing

application. -

Do not change the dressing for about 10

days (particularly in children) because anxiety and discomfort produced

by the dressing change often incite potentially irreversible vasospasm

in the replanted part (22). If there is

excessive bleeding into the dressing, change the dressing immediately

to prevent constriction from the blood-soaked dressings.

lower extremity) is less common than amputation of digits or parts of

the hand. In replantation of limbs amputated proximal to the wrist

level or of amputations of a lower extremity below or above the knee,

principles similar to

those

for digit replantation are used with minor modifications. The major

difference is related to the increased amount of muscle tissue

involved. Because more muscle mass is present in a major limb

amputation, the duration of ischemia of the detached part is more

critical. Whereas amputated digits that have been detached for 30 to 36

h may be replanted with a high degree of success, an amputated arm at

the elbow area is in jeopardy if it has been avascular for 10 to 12 h,

even with appropriate cooling. Rarely are major limbs cleanly severed;

therefore, the muscle damage is usually quite severe. Extensive muscle

debridement of both the detached part and the proximal stump is

essential to prevent myonecrosis and subsequent infection. This

problem, associated with major limb replantation, seldom occurs in

digital reattachment (46).

-

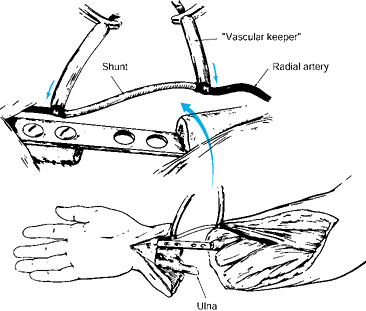

If the amputated part and the patient

arrive in the operating room more than 4 h after injury, initiate

immediate blood flow into the detached part. This is best accomplished

by using some form of shunt, such as a Sundt (Huger Shulte Corporation,

Galeta, CA) or ventriculoperitoneal shunt, to obtain rapid arterial

inflow from the proximal vessel to the detached part (61) (Fig. 34.12).![]() Figure 34.12.

Figure 34.12.

A Sundt or ventriculoperitoneal shunt is used to obtain rapid arterial

inflow from the proximal vessel to the amputated part. This is

particularly useful for major limb amputations that arrive in the

operating room more than 4 h after injury. (From Urbaniak JR.

Replantation in Children. In Serafin D, Georgiade NG, eds. Pediatric Plastic Surgery. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1984:1168.) -

Perform shunting before bone fixation

unless the bone can be rapidly stabilized and early blood flow

obtained. After establishing temporary blood flow, complete the

debridement, stabilize the bone, remove the shunts, and perform a

direct arterial repair or interposition vein grafting of the vessels.

-

For major limb replantation, the best

bone fixation is obtained with plates and screws. Cross-pin fixation of

the joint is usually the best method for stabilizing the amputations at

the joint level. -

Carefully plan adequate bone shortening

relative to the type of injury, tissue damage, proximity of the

epiphysis, and the particular limb involved. Usually the plate may be

secured to the amputated part after the initial debridement and then

fixed to the stump after blood flow has been established through the

shunts (if the ischemia time has been longer than 10 to 12 h).

injuries with extensive muscle and other soft-tissue damage, a great

deal of soft tissue, including skin, muscle, tendon, and nerve, must be

excised if the replanted part is to survive without infection. It is

therefore prudent to shorten the bone considerably when possible.

This sequence permits a physiologic washout of noxious agents, such as

lactic acid, in the distal part. If this order is reversed, with venous

repair first, the return of toxic metabolites to the systemic

circulation can cause serious consequences, even death. Giving

intravenous sodium bicarbonate before venous anastomosis is beneficial (23).

replantation. A common error is failure to decompress the replanted

limb adequately, leading to myonecrosis with subsequent infection.

Meshed split-thickness skin grafts provide some coverage of exposed

vessels. Other areas may be closed primarily or grafted several days

later.

-

In replantations of major limbs, return

the patient to the operating room within 48 to 72 h to evaluate the

state of the muscle tissue. -

Change the dressing with the patient under general or regional block.

hospitalized for 7 to 8 days. Major limb replantations, of course,

require longer periods, depending on the severity of the injury.

Intelligent, careful postoperative management is essential to achieve a

high success rate in replantation surgery (30).

and keep it warm at all times. The patient should stay in a warm,

comfortable room during the first week. If the recovery room is cooler

than normal room temperature, place a patient heater or a warmer over

the patient. Keep the patient’s room at a minimum of 72°F (22°C) and

prevent cool air drafts.

controversial. A few surgeons use none or perhaps only aspirin and di-

pyridamole; some use all or various combinations of anticoagulants (11,52,57,104). We prefer some type of anticoagulation for all patients.

amputations that are replanted or if the anastomosis was technically

easy and the blood flow was immediately brisk. In these patients, we

use aspirin, 300 mg, and dipyridamole, 50 mg, twice daily as well as

500 mg of intravenous low-molecular-weight dextran for 1 week. In

addition, we give chlorpromazine, 25 mg three or four times daily, for

a tranquilizing effect as well as to provide peripheral dilation. This

drug is valuable in relieving vasospasms secondary to anxiety, which

occurs particularly in children. In children, the dose is reduced to 10

mg three to four times daily by mouth.

intravenous heparin, 1,000 units every hour, in adults for 7 days.

Adjust this dosage in children, giving about 100 U/kg for 4 h. Adjust

this according to the activated partial thromboplastin time, which is

maintained at 1.5 times normal. If bleeding occurs into the dressing,

adjust the dosage and change the dressing immediately to prevent

constriction. Do not use heparin prophylaxis in amputations proximal to

the wrist level. Give appropriate antibiotics for 1 week.

The normal skin temperature of the digits is 31° to 35°C. Remember that

ambient temperature may influence the interpretation of the recordings.

Probes are usually placed on the replanted digits, on a normal digit

for control, and on the dressing for measurement of the ambient

temperature. An abrupt or even gradual change in temperature indicates

that the replant may be failing, and steps must be taken to improve the

blood flow. If the temperature drops below 30°C or shows more than a 2°

drop when compared with the normal digit, appropriate methods of

management must be undertaken immediately.

level or desire of the patient. If the patient is anxious and chooses

to remain in bed or appears to be having difficulty with blood flow to

the replanted part, then bed rest is advised for 3 to 5 days. If the

patient is vigorous or energetic, however, allow activity a day or two

after the replantation. Permit no smoking by the patient or in the

patient’s room, and all efforts should be made to keep the patient

tranquil (15).

because the dressing is not changed for at least 10 days, however,

immediate early motion is limited. In the patient who has had a

replantation distal to the superficialis insertion, encourage movement

of the digit the following day because there is really no stress on the

flexor or extensor tendons. Otherwise, begin protective active motion

against rubber bands and flexor and extensor outriggers, supervised by

a hand therapist, 1 to 2 weeks after the replantation. Especially for

replantation patients who live far from the treatment center, if more

than one digit has been replanted or a major limb has been replanted,

keep the patient in the hospital or in a nearby motel so that daily

therapy can be supervised by hand therapists.

-

Replantation in children under 10 years of age

-

Crush and avulsion injuries

-

Ring avulsion injuries

-

Poor proximal flow observed before the arterial anastomosis

-

Intermittent or inconsistent distal flow despite a technically good anastomosis

postoperative efforts are necessary to enhance the chances of survival.

Intravenous heparin is particularly beneficial in these difficult

replantations.

a regional sympathetic block is particularly helpful. Insert a #5

silicone urethral stent beside the median or ulnar nerve (depending on

the digits revascularized or replanted) to permit regional block to be

given in the postoperative course. The catheter exits from the dressing

and has a stopcock attached so that a nurse can give 5 mL of 0.25%

bupivacaine hydrochloride every 6 to 8 h. This drug provides regional

block anesthesia to diminish vasospasm and alleviate pain. This

procedure is particularly rewarding in children because it obviates the

use of axillary or brachial block if postoperative spasm develops. In

the postoperative period, we have rarely given an axillary or brachial

block since the early 1980s.

immediate postoperative period, as indicated by decreased skin

temperature, loss of capillary refill, diminished pulp turgor, or

abnormal color, immediately take the following steps:

-

Inspect the dressing to rule out any type of constriction. Administer intramuscular narcotics prior to inspection.

-

Depress or elevate the hand to improve the vascular status, depending on whether the problem is arterial or venous.

-

Give an intravenous bolus of heparin (3,000 to 5,000 U), which often incites recovery.

-

Give chlorpromazine to diminish anxiety and decrease vasospasm, if necessary.

-

Ensure that the patient is adequately hydrated and that the hematocrit is normal or near normal.

-

Alter the environment of the patient’s room (for example, increase the temperature and remove smokers or other agitating factors), if necessary.

-

Make all efforts to calm the patient, especially a child, as pain, fear, and anxiety may initiate peripheral vasospasm.

management measures, return the patient to the operating room. Once

this decision is made, do so within the first 4 to 6 h after the loss

of adequate perfusion. Seldom have we found reexploration to benefit

the patient if it occurs more than 1 to 2 days after replantation. If

the patient is returned to the operating room within the first 12 to 48

h, however, many potential failures can be salvaged by redoing the vein

graft, removing the thrombus, and usually grafting a previously

unrecognized damaged vessel segment.

replantations, loss of a replanted digit is rare secondary to

infection. The most common infections are pin tract infections, which

usually occur more than 4 weeks after the replantation and are easily

managed by removing the pins and putting the patient on antibiotics. We

have seldom found it necessary to admit a patient to the hospital for

pin tract infections.

replantations. The presence of large amounts of muscle that have been

rendered ischemic increases the likelihood of infection. To ensure

adequate muscle debridement, return all major limb replantations to the

operating room in 48 h for a “second look” procedure. At this time,

inspect the wounds thoroughly and debride any muscle necrosis that has

progressed since the first procedure. Infections in major limb

replantations may not become apparent until the second week (most

commonly in 8 to 10 days); if the infection involves the vascular

anastomosis, failure is almost inevitable.

patients who have undergone digital replantations. However, cold

intolerance is not unique to digital replantation and occurs with

almost equal incidence in other severe hand injuries, including

amputations that are not replanted (29). Cold

intolerance is related to the adequacy of digital reperfusion; for this

reason, try to maximize the number of arterial repairs. Cold

intolerance diminishes with time and usually resolves by 2 years (91). Pain is rare in successfully replanted limbs.

repaired in replantations, tendon adhesions are common, with diminished

motion. If this is severe, tenolysis may be performed as early as 3

months after replantation.

replantation. These complex injuries require multiple tendon, vessel,

and nerve repairs, and if care is not taken during bone fixation,

rotational malunion may occur.

Every

effort should be made to properly align digits before replantation.

Another form of malunion can occur in multiple digit replantations for

which it is difficult to identify the various digits at the time of

surgery. It may become apparent later that one digit has been exchanged

for another. This is primarily a cosmetic problem and does not result

in any diminished function.

80% viability in replantation of completely severed parts. Our team has

achieved 77% viability in replantations and 92% in revascularizations

of more than 1,800 amputations.

the experienced and proficient microsurgeon should be able to achieve

at least an 80% overall viability rate in replantations. The results,

based on our own long-term follow-up as well as reports from major

replantation centers, should be as follows:

-

The active range of joint motion should be about half of normal, depending on the level of injury.

-

Cold intolerance is a definite problem that usually subsides within 2 years.

-

Nerve recovery is comparable to the repair of an isolated, severed peripheral nerve (19).

-

Cosmesis is usually better than any amputation revision or prosthesis (29).

-

Near-normal growth may be anticipated in

amputations through the diaphyseal region of children. If the injury

involves the epiphyseal plate, growth will almost always be retarded,

although excessive growth has been reported (24,35,67). -

The best results are obtained in

replantations of the thumb, a finger distal to the insertion of the

superficialis tendon, and the hand at the wrist level.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.

H, Shieh S, Hsu H. Multivariate Analysis of Factors Influencing the

Functional Recovery after Finger Replantation for Revascularization. Microsurgery 1995;16:713.

NK, Gerostathopoulos N, Efstathopoulos D, et al. Major Amputation of

the Upper Extremity. Functional Results after

Replantation/Revascularization in 47 Cases. Acta Orthop Scand [Suppl] 1995;264:7.

RD, Stevanovic MV, Nunley JA, Urbaniak JR. Digital Replantation at the

Level of the Distal Interphalangeal Joint and the Distal Phalanx. J Hand Surg 1989;14:214.

RB, O’Brien BM, Morrison A, MacLeod AM. Survival Factors in

Replantation and Revascularization of the Amputated Thumb—10 Years’

Experience. Scand J Plast Reconstruct Surg 1984;18:163.

SER, Adrichem LNA, Mulder HD, et al. Comparison of Laster Doppler

Flowmetry and Thermometry in the Postoperative Monitoring of

Replantations. J Hand Surg 1997;38:151.

N, Cooley BG, Kamiishi J. Clinical Outcome of Digital Replantation

using the Fibrin Glue-Assisted Microvascular Anastomosis Technique. J Hand Surg 1996;21B:573.

TF, Arnex ZM, Solinc M, Zaletel-Kragelj L. One Hundred Sixty-Seven

Thumb Replantations and Revascularisations: Early Microvascular

Results. Microsurgery 1996;17:259.

K, Sinokawa Y, Kishibe M. The Venocutaneous Fistula: A New Technique

for Reducing Venous Congestion in Replantation Fingertips. Plast Reconstruct Surg 1997;99:171.

JD, Kleinert HE, Tsai T-M. Methods and Results of Replantation

Following Traumatic Amputation of the Thumb in 64 Patients. J Hand Surg 1980;5:63.

People’s Hospital, Shanghai. Replantation of Severed Fingers: Clinical

Experience in 162 Cases Involving 270 Severed Fingers. Pamphlet July

1963.

Y, Ishikawa K, Isshiki N, Takami S. Fingertip Replantation with an

Efferent A-V Anastomosis for Venous Drainage: Clinical Reports. Br J Plast Surg 1993;46:187.

N, Sharzer LA, Starker I. Replantation and Revascularization at the

Transmetacarpal Level: Long-Term Functional Results. J Hand Surg 1990;15A: 328.

S, Nomura S, Yoshimura M, et al. A Clinical Study of the Order and

Speed of Sensory Recovery after Digital Replantation. J Hand Surg 1983;8:45.

T, Katsumi M, Tajima T. Replantation of Untidy Amputated Finger, Hand

and Arm: Experience of 99 Replantations in 66 Cases. J Trauma 1978;18:194.

C, Meyer VE, Kleinert HE, Beasley RW. Present Indications and

Contraindications for Replantations as Reflected by Long-term

Functional Results. Orthop Clin North Am 1981;12:849.