Pelvis and Acetabulum

interconnecting ligaments. It consists of the two innominate bones,

which articulate anteriorly with each other at the pubic symphysis and

posteriorly with the body of the sacrum at the sacroiliac joint. The

bones are covered on each side by muscles, and the intraabdominal

contents make surgical exposure potentially complex. The presence of a

large subcutaneous surface (the iliac crest), however, allows safe

access to the ilium.

chapter, all of which provide access to the bone via its subcutaneous

portion. The anterior and posterior approaches to the iliac crest are

used almost exclusively for bone grafting. The anterior approach to the

pubic symphysis, and the anterior and posterior approaches to the

sacroiliac joints are performed rarely; their use is associated almost

exclusively with the open reduction and internal fixation of pelvic

ring fractures.

demanding approaches a surgeon can be asked to perform. They are nearly

always used for the reconstruction of the acetabulum following

fractures. Because each approach only gives access to a limited part of

the acetabulum, it is critically important that the correct approach is

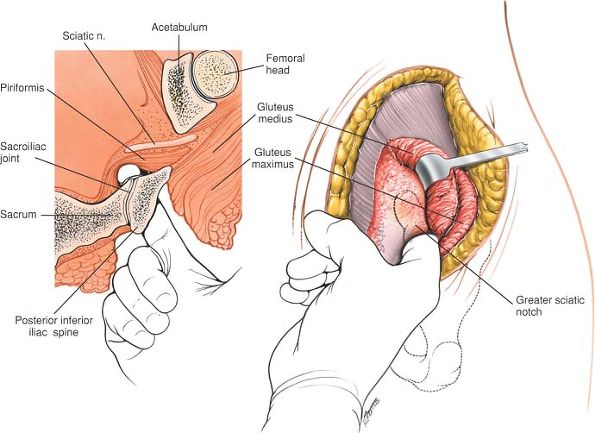

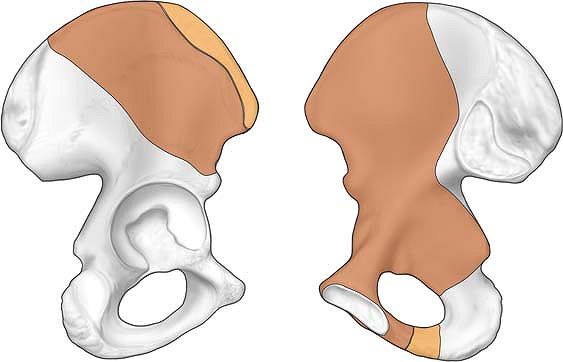

used for each fracture pattern (Fig. 7-1). This

requires accurate assessment of the anatomy of the fracture, using

radiographic techniques, including computerized tomography.1,2,3 The

use of a bone model is invaluable, especially when a surgeon is inexperienced.

|

|

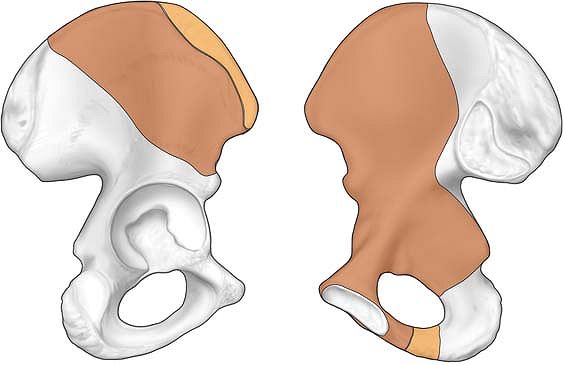

Figure 7-1

To appreciate the anatomy of the anterior and posterior columns of the acetabulum, hold a hemipelvis up against a light source. These two massive columns can then be appreciated in contrast to the thin central area of the wing of the ilium. |

access to the anterior column and medial aspect of the acetabulum. It

also allows visualization of the inner aspect of the pelvis from the

sacroiliac joint to the symphysis pubis. It does not allow access to

the posterior column or posterior lip (see Fig. 7-21).

to the posterior column, posterior lip, and dome segment of the

acetabulum. It allows very limited access to the anterior column of the

acetabulum and no access to the medial aspect of the acetabulum (see Fig 7-37).

approach is to be found immediately after the description of the

surgical approach. The applied surgical anatomy of the posterior

approach is found in Chapter 8 (see page 450).

the acetabulum, complex fractures may require the use of more than one

approach.

violent trauma. The tissues therefore are contused, and muscle planes

are often difficult to develop. The fractures themselves are difficult

to reduce, and control and specialized instruments are necessary to

ensure anatomical reduction and stable fixation. There is rarely, if

ever, indication to perform these approaches in an emergency situation.

Acetabular fractures are rare. Understanding of the anatomy of the

fracture is difficult, and surgical approaches are technically

demanding. The results of acetabular reconstruction depend largely on

the accuracy of the reduction of the fracture. For these reasons,

acetabular surgery, if at all possible, should be performed by

experienced surgeons working in centers large enough to attract a

sufficient volume of patients.

used grafts in orthopaedic surgery. The iliac crest is subcutaneous,

and cortical or corticocancellous grafts can be taken from it with ease

and safety for grafting in all parts of the body, including the spine.

It also is possible to remove pieces of the iliac crest, including both

cortices, for major bone reconstructions, especially in the head and

neck. For posterior spinal fusion work on conditions such as scoliosis,

the bone graft usually is taken from the posterior aspect of the iliac

crest.

the graft usually is taken in conjunction with other procedures, the

iliac crest should be draped as a separate unit. There is much to be

said for preparing this area routinely in all cases of open reduction

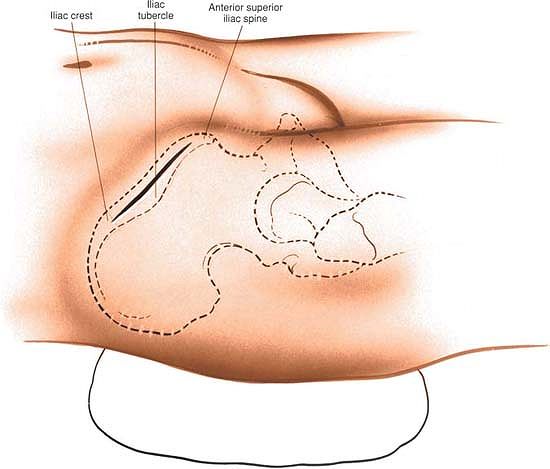

and internal fixation of long-bone fractures. Place a small sandbag

under the gluteal (cluneal) area of the side from which the graft will

be taken to elevate the crest and rotate it internally, making it more

accessible.

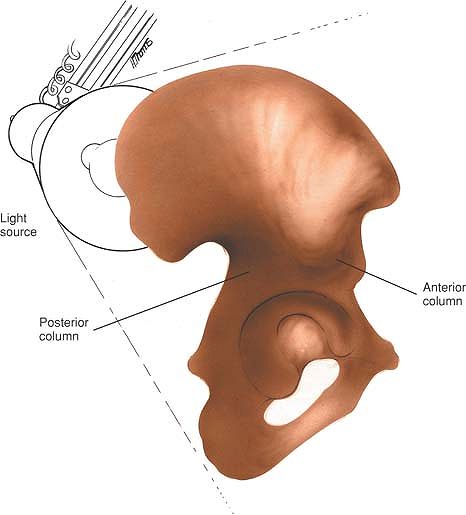

the most important landmark, is easily palpable. Continue palpating

along the crest of the ilium until its widest portion is reached, at

the iliac tubercle. The iliac tubercle marks the anterior portion of the ilium, the area containing the largest amount of cortical cancellous bone for graft material.

graft that is required. For an extensive bone graft make an 8-cm

incision parallel to the iliac crest and centered over the iliac

tubercle (Fig. 7-2).

crest, but do not cross it. Therefore, the crest offers a truly

internervous plane.

medius are the muscles affected most directly by grafts taken from the

anterior portion of the crest, because they originate from the outer

portion of the ilium and are supplied by the superior gluteal nerve.

The abdominal muscles take their origin directly from the iliac crest

and are supplied segmentally.

the crest still may be an avascular apophysis. If so, incise it and

remove the muscle through the crest in either direction with a Cobb

elevator. No apophysis will be present in adults.

|

|

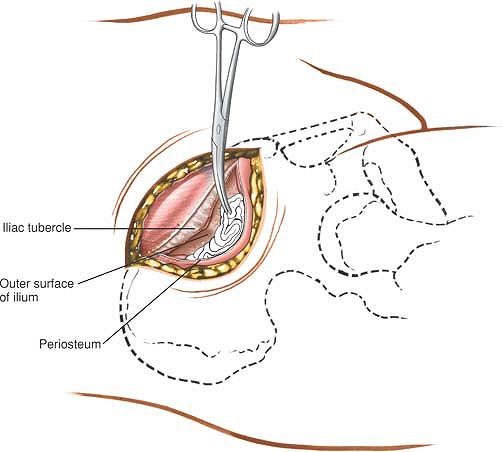

Figure 7-2 Make an 8-cm incision parallel to the iliac crest and centered over the iliac tubercle.

|

or iliac crest onto the anterior superior iliac spine itself; if this

occurs, the origin of the inguinal ligament may be detached and an

inguinal hernia may result.

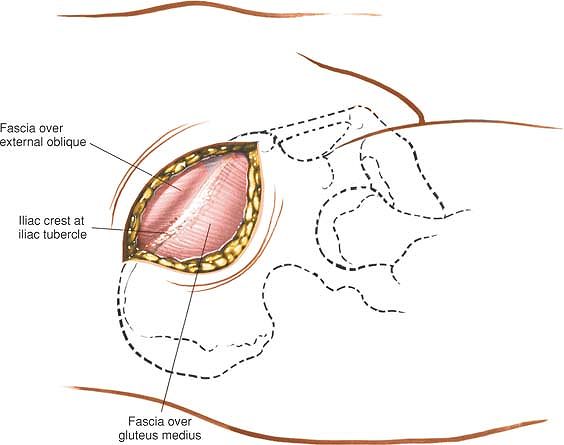

outer wall of the ilium. Initially, cut down onto the bone using a

scalpel. Follow the contour of the bone, sticking to it rigidly (Fig. 7-4).

Below the crest itself, the ilium narrows considerably, so the sharp

dissection will need to follow the contour of the bone carefully to

avoid straying out of plane and into trouble. After coming around the

corner of the crest onto the ilium, continue the dissection using blunt

instruments such as a Cobb elevator. The muscles will come away from

the bone easily. Alternatively, push a swab into the plane between the

iliac wing and the overlying muscles. Using a blunt instrument,

introduce more and more of the swab into the plane. The swab will act

as a tissue expander, pushing the muscle away from the bone, while at

the same time protecting the soft tissues. Corticocancellous strips may

be taken from either side of the bone, or a complete block of the ilium

can be removed. Pure cancellous bone can be taken by elevating a small

piece of the cortex of the crest. Be aware that the largest supply of

cancellous bone is directly underneath the subcutaneous surface of the

crest.

iliac spine should be left intact to preserve the normal appearance of

the pelvis. If the anterior superior iliac

spine is taken as graft material, the inguinal ligament might retract, causing an inguinal hernia.

|

|

Figure 7-3 Retract the skin, identify the iliac crest, and incise the soft tissues overlying the iliac crest down to bone.

|

|

|

Figure 7-4 Remove the origins of the gluteus minimus and medius muscles subperiosteally from the outer cortex of the ilium.

|

either the gluteal muscles from the outer cortex or the iliacus muscle

from the inner cortex. Placing a swab between the retractor and the

muscles creates a bloodless field and prevents little pieces of bone

graft from being lost in the depth of the wound. Great care must be

taken, however, to remove this swab before undertaking closure. The

incision may have to be lengthened on the iliac crest and additional

amounts of gluteus medius or iliacus stripped off to provide a better

view of the outer or inner cortex of the anterior portion of the ilium.

has been described in this section merely as a means of obtaining bone

graft.

during any posterior spine surgery that requires additional autogenous

bone to supplement the area to be fused. The grafts also may be used as

corticocancellous grafts for any part of the skeleton that needs fusion

or refusion.

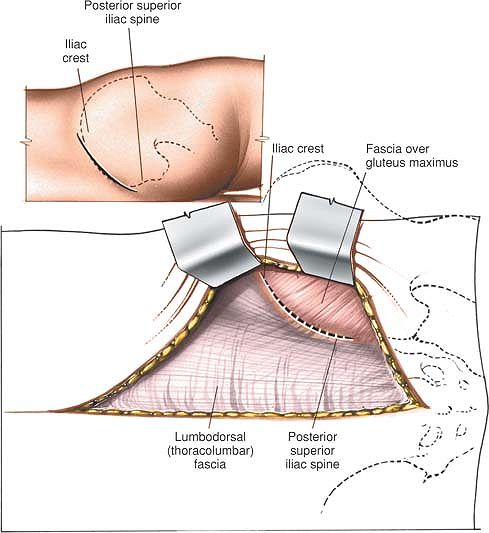

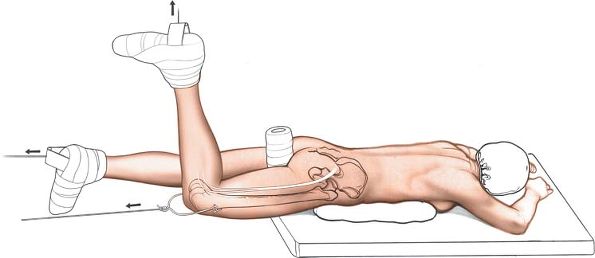

bolsters running longitudinally to support the chest wall and pelvis,

allowing the chest wall and abdomen to expand without touching the

table. Place drapes distally enough so that the beginning of the

gluteal cleft and the posterior superior iliac spine can be seen (see Fig. 6-83).

performed, the midline incision can be extended distally to the sacrum.

Then, the skin and a thick, fatty, subcutaneous layer can be retracted

laterally. Using a Hibbs retractor, the flap should be dissected free

from the underlying lumbodorsal fascia until the posterior superior

iliac spine and crest can be palpated and seen (see Fig. 7-5).

but do not cross it. Therefore, the outer border of the iliac crest is

truly an internervous plane. The gluteus medius, minimus, and maximus

muscles take their origins from the outer surface of the ilium (the

gluteus medius and minimus are supplied by the superior gluteal nerve

and the gluteus maximus is supplied by the inferior gluteal nerve). The

segmentally supplied paraspinal muscles take their origin from the

iliac crest itself, as does the latissimus dorsi, which is supplied

proximally by the long thoracic nerve. Thus, an incision into the iliac

crest does not denervate muscles, even if it is not placed exactly on

the outer lip of the crest.

iliac crest is reached. In children, the iliac apophysis is white and

quite visible; it may be incised or split in line with the iliac crest,

using it as an avascular plane. In adults, the apophysis is ossified

and fused to the crest; the incision lands directly on the crest itself.

or muscles from the iliac crest both medially and laterally, to bare

the surface of the posterior portion of the crest.

|

|

Figure 7-5

If lumbar spine surgery is being performed, extend the midline incision distally, retracting the skin laterally until the posterior superior iliac spine and crest can be palpated and seen. Incise the soft tissues overlying the crest down to bone. Make an 8-cm oblique incision, centered over the posterior superior iliac spine and in line with the iliac crest (inset). |

iliac crest. They can be avoided by placing the incision no more than 8

cm anterolateral to the posterior superior iliac spine. The nerves

supply sensation to the skin over the cluneal (gluteal) area. They are

composed of the posterior primary rami of L1, L2, and L3. Their loss

does not cause problems for the patient.

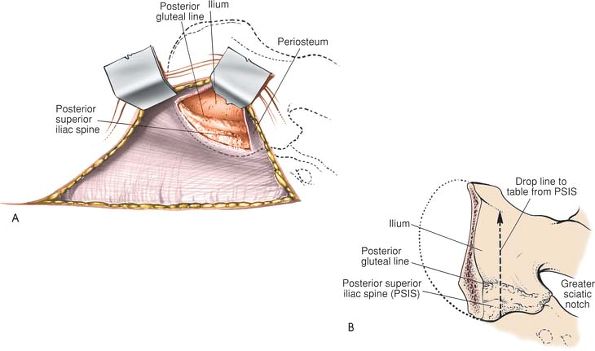

portion of the lateral surface of the ilium so that a large enough

graft can be obtained. Take care to stay in a subperiosteal plane while

passing from the iliac crest to the outer cortex of the ilium.

Proceeding 1.5 cm down the ilium in the area of the posterior superior

spine, the elevated posterior gluteal line can be seen and felt; pass

subperiosteally up over the line and then down its other side. Do not

err by letting the line direct the incision outward from bone into

muscle. A Taylor retractor will help the exposure by holding the

muscles laterally. Note that the posterior gluteal line separates the

origins of the gluteus maximus (posterior) from the gluteus medius

(anterior; Fig. 7-6).

which runs close to the distal end of the wound deep to the sciatic

notch; however, if an imaginary line is drawn from the posterior

superior iliac spine perpendicular to the operating table, and all work

is performed cephalad to it, both the notch and the nerve will be

avoided completely. If a larger graft is necessary, palpate the sciatic

notch itself before taking the graft (see Fig. 7-6B).

a branch of the internal iliac (hypogastric) artery, leaves the pelvis

via the sciatic notch, staying against the bone and proximal

to

the piriformis muscle. If a graft is taken too close to the sciatic

notch, the vessel may be cut and may retract into the pelvis. Nutrient

vessels from the artery supply the iliac crest bone along the

midportion of the anterior gluteal line, and the vessel may become an

osseous bleeder as it enters bone via the nutrient foramen. To control

bone bleeding, use bone wax on the raw cancellous surface of the pelvis

after the graft has been removed.

|

|

Figure 7-6 (A) Subperiosteally, strip the musculature off the posterior portion of the lateral surface of the ilium. (B)

Proceeding down the outer surface of the ilium in the area of the posterior superior spine, the elevated posterior gluteal line can be seen and felt; pass subperiosteally up and over the line and then down its other side. Do not err by letting the line direct you outward from bone to muscle. If you draw an imaginary line from the posterior superior iliac spine perpendicular to the operating table and stay cephalad to it, you will avoid the sciatic notch and its contents. |

Breaking through the thick portion of the bone that forms the notch

disrupts the stability of the pelvis. Removal of bone from the false

pelvis proximal to the notch does not cause loss of stability (see Fig. 7-6B).

the bone to retract the gluteal muscles away from the bone and increase

the exposure. To increase the exposure further, lengthen the iliac

crest incision and strip more of the gluteal muscles from the outer

cortex to avoid working through a “keyhole.”

specifically for removing bone for graft material from the posterior

outer cortex of the ilium. Inner cortex also may be taken, but soft

tissues should not be stripped off the anterior (deep) aspect of the

ilium.

approach that is used almost exclusively for the open reduction and

internal fixation of a ruptured symphysis or internal fixation of a

displaced fracture of the superior pubic ramus. Other uses include

biopsy of tumors and treatment of chronic osteomyelitis.

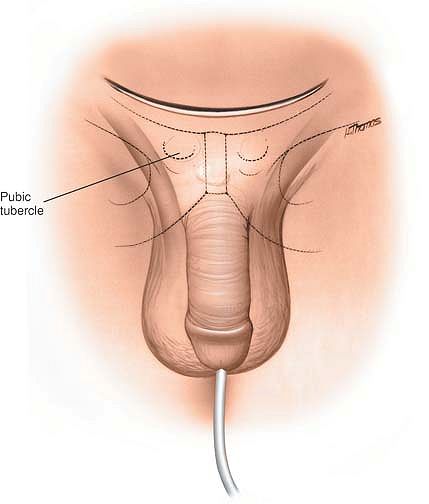

associated with urologic damage, obtaining a urologic assessment is

advisable before undertaking open surgery, which often includes a

retrograde urethrogram. A urethral catheter must be inserted before

surgery. A full bladder will seriously interfere with the surgical

approach.

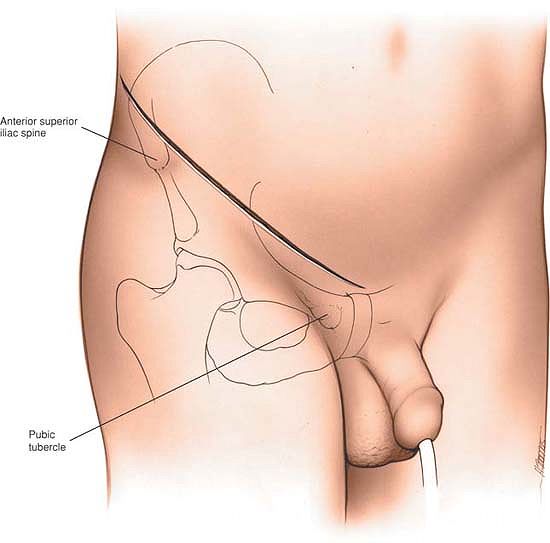

are easily palpable in all but the most obese patients. The pubic

symphysis will be palpable (as a gap) only in cases of rupture.

|

|

Figure 7-7

Palpate the pubic tubercles. Make a curved incision in the line of the skin crease, centering it 1 cm above the pubic symphysis. |

approach. Because the rectus abdominis muscles receive a segmental

nerve supply, they are not denervated, even though they are divided by

this approach.

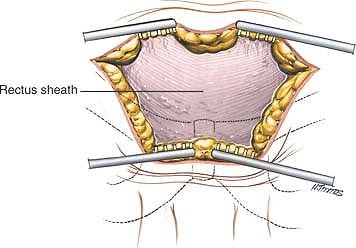

incision, deepening the incision down to the anterior portion of the

rectus sheath (Fig. 7-8). Identify, ligate, and

divide the superficial epigastric artery and vein that run up from

below across the operative field. Then, divide the rectus sheath

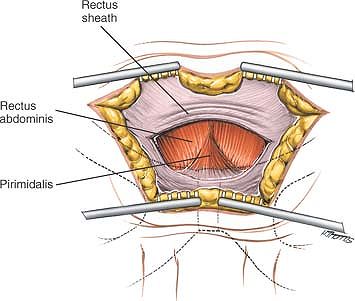

transversely,

about 1 cm above the symphysis pubis. The two rectus abdominal muscles now are visible (Fig 7-9).

In most cases of rupture of the symphysis pubis, one of these muscles

will have been detached from its insertion into the pubic symphysis.

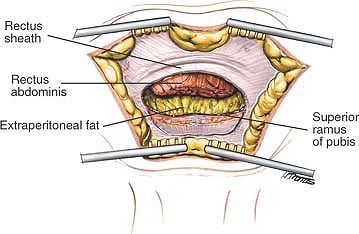

Divide the remaining muscle a few millimeters above its insertion into

the bone.

|

|

Figure 7-8 Incise the fat in the line of the skin incision and retract the skin edges to reveal the anterior portion of the rectus sheath.

|

If access to the back of the symphysis is required, use the fingers or

a swab to push the bladder gently off the back of the bone. Palpation

of the posterior surface of the body of the pubis is useful to identify

the correct direction for the insertion of screws. This dissection is

very easy to perform unless adhesions have formed due to damage to the

bladder. Such adhesions make it difficult to open up this potential

space (the preperitoneal space of Retzius) (Fig. 7-11). The pubic symphysis and superior pubic rami now are exposed adequately for internal fixation.

|

|

Figure 7-9 Divide the rectus sheath transversely 1 cm above the symphysis pubis to reveal the rectus abdominis muscles and pyramidalis.

|

damaged during the trauma. If so, adhesions will have developed between

the damaged bladder and the back of the pubis. Mobilization of the

space of Retzius, therefore, may lead to inadvertent bladder rupture.

If fixation is considered in

the presence of urologic damage, it is best to operate in conjunction with an experienced urologic surgeon.

|

|

Figure 7-10

Divide the rectus muscles 1 cm above their insertion and retract their cut edges superiorly to reveal the superior ramus of the pubis. |

in this area, it may be necessary to extend the skin incision and

superficial dissection in both directions to allow better visualization

of the deep structures in obese patients.

|

|

Figure 7-11 (A) Open the plane behind the symphysis pubis, using your finger as a blunt dissector. (B) The pubic symphysis and superior pubic rami now are exposed.

|

safe, reliable access to that structure and allows anterior plates to

be positioned accurately across the joint. It also permits the exposure

of the inner wall of the ala of the ilium, allowing fixation of

associated iliac fractures. Paradoxically, although the sacroiliac

joint is one of the most posterior structures in the entire pelvic

ring, the anterior approach allows greater exposure and control than

does the seemingly more logical posterior approach, because of the

shape of the joint. Anteriorly, the joint is flat and directly

available, whereas posteriorly it is overhung by the posterior iliac

crest.

table and put a large sandbag under the buttock. The iliac crest should

be pushed up toward the surgeon. Support the opposite iliac wing with a

support attached to the operating table and then tilt the table 20°

away, allowing the mobile contents of the pelvis to fall away.

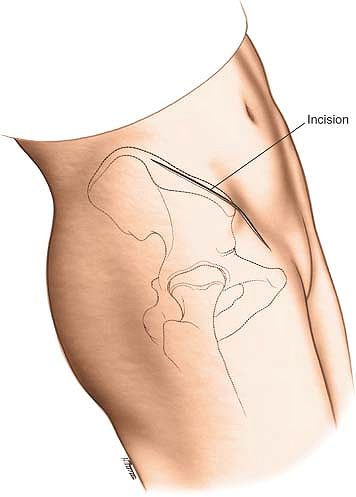

beginning 7 cm posterior to the anterior superior iliac spine (at about

the level of the iliac tubercle). Curve the incision forward until the

anterior superior iliac spine is reached. Continue the incision

anteriorly and medially along the line of the inguinal ligament for an

additional 4 to 5 cm (Fig. 7-12).

approach consists simply of stripping muscles off the pelvis; because

the bone is being approached via its subcutaneous surface, no muscle is

denervated.

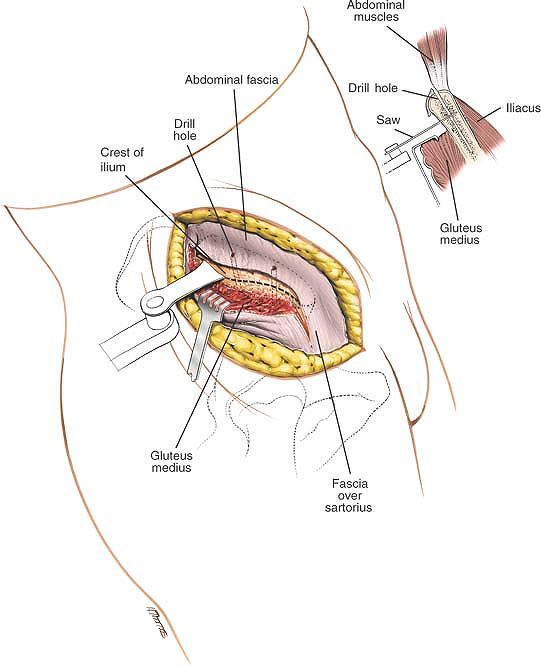

Expose the deep fascia overlying the glutei and tensor fasciae latae

muscles at the point where it attaches to the outer lip of the iliac

crest. Next, incise the periosteum of the entire anterior third of the

iliac crest and gently strip the muscles off the outer wall of the

pelvis to expose about 1 cm of the outer surface below the crest of the

ilium. Predrill the iliac crest for easy reattachment. Using an

oscillating saw, transect the wing of the ilium at this level, cutting

only the outer cortex and the cancellous bone underneath (Fig. 7-13).

Next, crack the inner cortex with an osteotome. This allows the

anterior superior iliac spine to be detached along with the transected

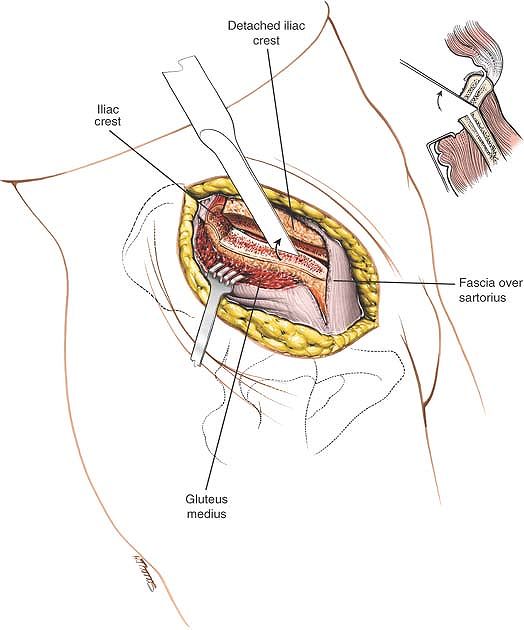

portion of the iliac wing (Fig. 7-14).

ilium; detach it by blunt dissection. As the dissection is deepened,

the detached anterior superior iliac spine, which still is attached to

the lateral end of the inguinal

ligament,

must be mobilized. This block of bone and muscle must be moved

medially; to accomplish this, divide some fibers of both the tensor

fasciae latae and sartorius muscles (Fig. 7-15).

Note that the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh is very close to the

anterior superior iliac spine and may have to be divided to permit this

mobilization.

|

|

Figure 7-12

Make a curved incision over the iliac crest, beginning 7 cm posterior to the anterior superior iliac spine. Curve the incision anteriorly and medially along the line of the inguinal ligament for 5 cm. |

|

|

Figure 7-13

Strip the muscles from the outer wall of the pelvis. Predrill the iliac crest. Divide the outer cortex 1 cm below the crest using an oscillating saw. |

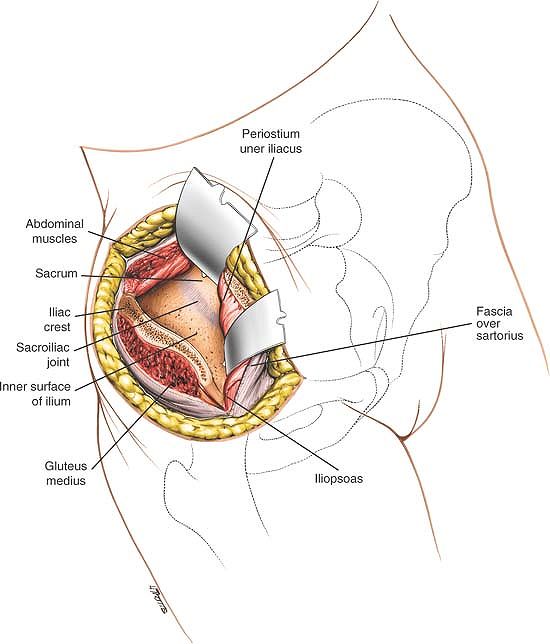

iliacus muscle off the inner wall of the pelvis to expose the

underlying sacroiliac joint (see Fig. 7-15).

The distance is surprisingly short. As the muscle is stripped off, some

nutrient vessels will have to be detached from the inner wall of the

pelvis. Bleeding usually can be controlled by bone wax. Mobilizing the

iliacus muscle off the inside of the pelvis with a large bone block

allows the muscles to be reattached securely with screws during

closure. The muscle then resumes its anatomic position, and the dead

space beneath it is obliterated. Failure to securely reattach the iliac

crest will produce impaired function, a poor cosmetic result, possible

chronic pain, and a high risk of hematoma formation.

superior iliac spine. This will cause some numbness of the lateral aspect of the thigh.

|

|

Figure 7-14 Crack the inner cortex using an osteotome to complete the iliac osteotomy.

|

they arise from the sacral foramina. For this reason, the dissection

cannot be carried further medially than the sacral foramina. The sacral

nerve roots are not usually exposed during this approach. They can be

at risk at two stages of the operation. If sharp pointed retractors

such as Homans are used medially, great care should be taken that the

point of these retractors is not inadvertently inserted into a sacral

foramen. Sacral nerve roots can also be entrapped under the medial end

of plates applied to the anterior surface of the sacroiliac joint.

Meticulous preoperative planning will allow you to know exactly how

many screw holes can be inserted safely into the sacrum without

endangering the sacral nerve roots. In most cases, only one screw can

be inserted.

the inner wall of the ilium. Bleeding from these vessels can be

controlled by pressure or bone wax.

posteriorly placed sacroiliac joint is adequate anterior dissection.

The lateral end of the inguinal ligament and its attached anterior

superior iliac spine must be mobilized to visualize the sacroiliac

joint adequately.

ilioinguinal approach that provides access to the entire anterior

column of the acetabulum. This approach is discussed in Chapter 8.

|

|

Figure 7-15 Strip the iliacus from the inner wall of the pelvis to expose the underlying sacroiliac joint.

|

simple, safe approach that does not endanger any vital structures. Its

uses include open reduction and internal fixation of disruptions of the

sacroiliac joint, open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of

the ilium near the joint, and treatment of infections of the sacroiliac

joint or surrounding bones. The popularity of this approach has

diminished with the increasing use of percutaneous screw fixation

techniques. It is still, however, invaluable if adequate imaging is not

possible or if alternative techniques, such as plating, are used.

dislocations is difficult through this approach, especially the

correction of vertical displacement. Vertical displacement should be

corrected by longitudinal traction, preferably preoperatively.

demanding because of the shape of the joint and the presence of the

sacral nerve roots arising from the

sacral

foramina. Practice the direction of screw placement on a bone model

before surgery is attempted. During surgery, strict radiological

control of screw fixation using two plane C-arm imaging is mandatory.

Safe screw fixation can also be facilitated by the use of

computer-assisted surgery, if such technology is available to the

operating surgeon.

bolsters longitudinally to support the chest wall and pelvis; the

bolsters should allow the chest wall and abdomen to expand without

touching the table. Take great care during preparation and draping to

exclude the contaminated anal region from the operative field.

|

|

Figure 7-16

Make a curved incision, beginning 3 cm distal and lateral to the posterior superior iliac spine. Cross the posterior superior iliac spine and continue along the crest to its highest point. |

crest, beginning 3 cm distal and lateral to the posterior superior

iliac spine. Extend the incision from this spot to the posterior

superior iliac spine and then continue along the crest to its highest

point (Fig. 7-16).

gluteus maximus and gluteus medius muscles must be detached partially

from their origins, but their individual neurovascular pedicles are

preserved easily.

incision. Anteriorly, small cutaneous nerves (the superior cluneal

nerves) may have to be cut, but they are of little clinical

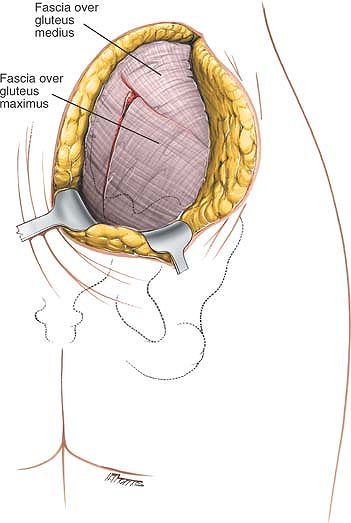

significance. Cut down into the outer border of the subcutaneous

surface of the iliac crest to reveal the layer of fascia that covers

the gluteus maximus muscle. Detach the origin of the gluteus maximus

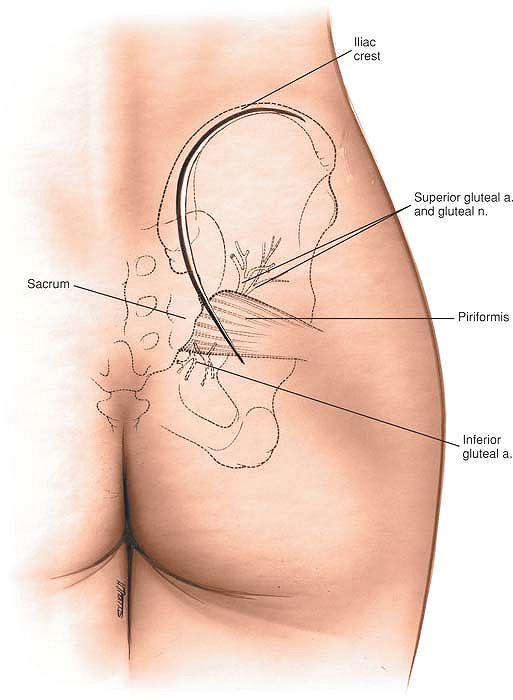

from the crest and carefully reflect the muscle downward and laterally (Fig. 7-17).

Two vital structures penetrate this muscle from its deep surface.

First, branches from the inferior gluteal artery, which emerge from the

pelvis, with the piriformis muscle through the greater sciatic notch,

penetrate the muscle. In addition, the inferior gluteal nerve emerges

from the notch beneath the piriformis to supply the muscle. Because it

is imperative that these two structures be preserved, they limit the

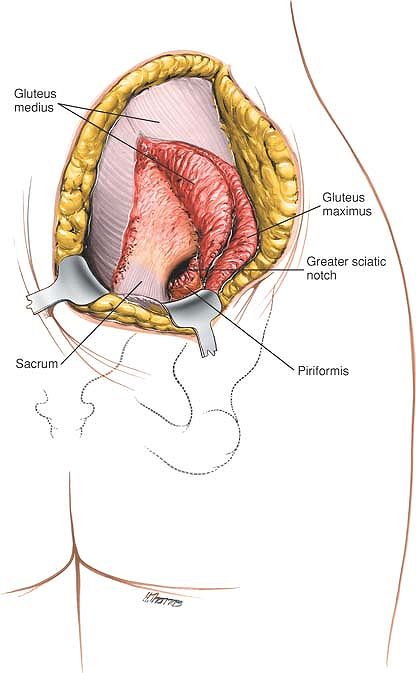

inferior mobilization of the muscle. As the gluteus maximus muscle is

reflected, the gluteus medius and piriformis muscles will be uncovered

as they emerge through the greater sciatic notch.

|

|

Figure 7-17 Divide the subcutaneous fat and reflect the skin flap to reveal the fascia overlying the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius.

|

wing of the ilium. The muscle cannot be elevated much anteriorly

because its deep surface is tethered by its neurovascular bundle—the

superior gluteal nerves and vessels (Fig. 7-18). In cases of trauma, the ruptured sacroiliac joint or fracture is easily visible, but reduction is extremely difficult. To

evaluate any reduction, detach part of the origin of the piriformis

muscle from around the greater sciatic notch and insert a finger

through the notch to palpate the joint from its anterior surface. The

surface of the joint will feel smooth if it has been reduced (Fig. 7-19).

|

|

Figure 7-18 Reflect the gluteus maximus muscle and the gluteus medius from the outer surface of the pelvis.

|

enters the deep surface of the gluteus maximus muscle. Overzealous

downward retraction of the muscle can cause a traction injury to this

nerve.

also enters the deep surface of the gluteus medius muscle. This limits

the forward retraction of this muscle, restricting the exposure of the

outer wing of the ilium. Excessive retraction of the muscle will injure

the superior gluteal nerve.

not endangered by the surgical approach but can be injured by

inaccurate screw fixation across the sacroiliac joint. Accurate x-ray

control of screw placement is mandatory.

gluteus medius and gluteus minimus muscles elevated from the outer side

of the iliac wing. This will enable more extensive fractures of the

wing and the ilium to be dealt with.

access via a subcutaneous portion of the bony pelvis. Thereafter,

access is afforded by stripping the muscular coverings off the bone

while remaining in a strictly subperiosteal plane. Using this

technique, the approaches avoid vital structures and, therefore, are

extremely safe. More muscles must be stripped and the view becomes

poorer, however, the further one proceeds from a subcutaneous part of

the bone. For this reason, these approaches are limited in the exposure

they provide. They cannot be extended and afford only limited access to

certain portions of the bony skeleton.

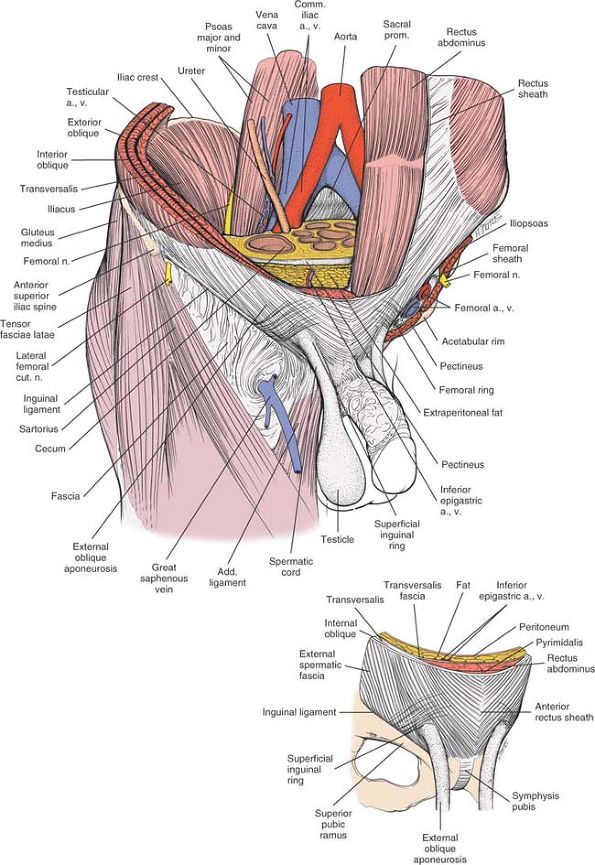

for access. The iliac crest has the external oblique and transversus

abdominis muscle arising from its surface. The wing of the ilium itself

is sandwiched between

two

masses of muscles, the glutei and tensor fasciae latae muscles on the

outer side, and the iliacus muscle on the inner side. The pubic

tubercles and upper parts of the superior pubic rami have the rectus

abdominis muscle attached to them, and these must be detached for

access to the superior surface of the structures.

is the site of insertion of the inguinal ligament and the sartorius

muscle. The anterior third of the iliac crest is the site of origin for

the external oblique, transversus abdominis, and tensor fasciae latae

muscles.

site of origin of the external oblique muscle. The posterior superior

iliac spine is marked by an overlying dimple. A line connecting these

dimples crosses the sacroiliac joint at the level of S2. The pubic

tubercle is the medial attachment of the inguinal ligament and the most

lateral part of the body of the pubis.

|

|

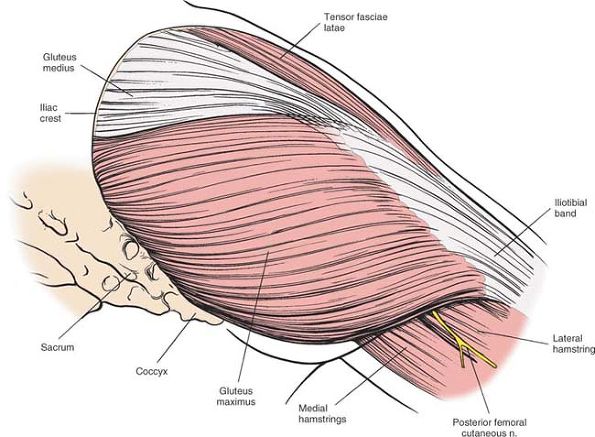

Figure 7-20 The superficial musculature of the posterior approach to the hip joint. The gluteus maximus predominates.

Gluteus Maximus. Origin.

From posterior gluteal line of ilium and that portion of the bone immediately above and behind it; from posterior surface of lower part of sacrum and from side of coccyx; and from fascia covering gluteus medius. Insertion. Into iliotibial band of fascia lata and into gluteal tuberosity. Action. Extends and laterally rotates thigh. Nerve supply. Interior gluteal nerve. |

of cleavage. Scars can be broad and ugly, however, but this rarely is

of clinical significance because they usually are covered with clothing.

consists of incising down onto the superficial portion of the bone. In

the iliac crest, this merely involves dividing the

overlying

fat. In the symphysis pubis, the rectus sheath must be opened. The

rectus sheath is a tough fibrous structure derived from all three

muscles of the anterior abdominal wall. It forms a tough anterior

covering to the underlying rectus muscle, which is easy to repair (see Fig 7-9).

anterior third of the iliac crest, but only from the outer aspect of

the posterior third of the crest.

detaching the origin of the tensor fasciae latae. Covering this muscle

is a thick layer of fascia that is continuous with the fascia covering

the gluteus maximus muscle. The tensor fascia latae, gluteus maximus

and the fascia can therefore be thought of as the outer layer of the

buttock anatomy (Fig. 7-20). This is analogous

to the position of the deltoid muscle in the shoulder. Deep to the

structures are the origins of the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus

muscles from the outer wing of the ilium. These can be lifted off the

bone entirely to provide a view of the wing of the ilium. It is

important to realize, however, that the rectus femoris muscle still

remains between the surgeon and the hip joint, thus limiting the

approach.

iliacus muscle. This can be lifted off the bone safely, providing

access down to the brim of the true pelvis.

joint, yet any movement is very difficult to demonstrate. The joint is

reinforced heavily by anterior and posterior supporting ligaments.

Approached from the front, the sacroiliac joint is perpendicular to the

plane of dissection. Approached from the rear, the joint is overhung by

the posterior iliac crest, making it oblique to the plane of

dissection. It is critically important to appreciate this obliquity

when planning the insertion of any screws that may be used to cross the

joint.

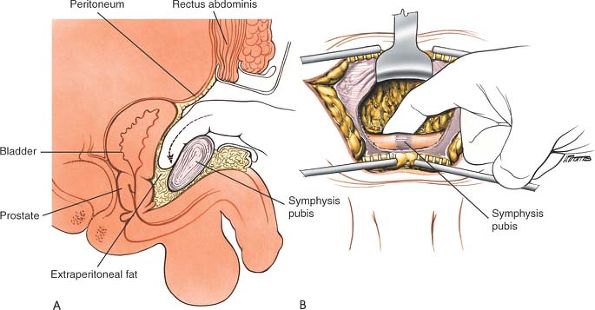

joint, but a secondary cartilaginous joint. Its superior surface is

readily accessible once the insertion of the rectus abdominis muscle

has been detached. Behind the symphysis pubis is a potential space

filled with loose areola tissue; this is known as the cave of Retzius.

This potential space lies between the symphysis pubis and the bladder,

and allows access to the inner surface of the pubis down to the muscles

of the pelvic floor.

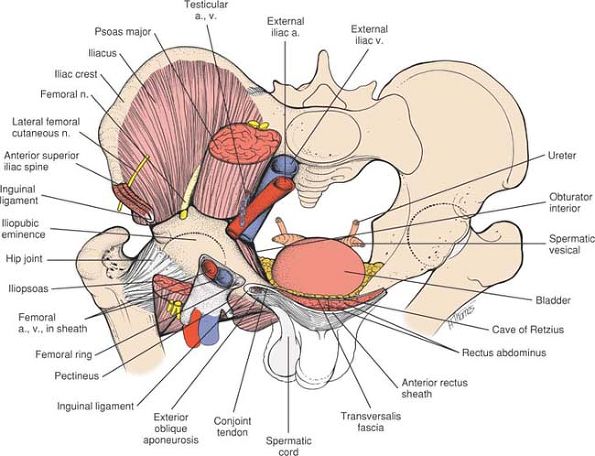

It allows visualization of the anterior and medial surfaces of the

acetabulum and is, therefore, suitable for exposure of anterior column

fractures of the acetabulum. It also allows insertion of screws into

the posterior column. The dissection involves isolating and mobilizing

the femoral vessels and nerve, as well as the spermatic cord in the

male and the round ligaments in the female. Because orthopaedic

surgeons usually do not operate in this area, operating in conjunction

with a general surgeon may be advisable. Alternatively, cadaveric

dissection should be performed before embarking on this exposure.

greater trochanter at the edge of the table. This allows the buttock

muscles and gluteal fat to fall posteriorly away from the operative

plane. Insert a urinary catheter. A full bladder will obscure vision.

thumbs medially along the inguinal creases and obliquely downward until

you can feel the pubic tubercle.

anterior superior iliac spine. Extend the incision medially, passing 1

cm above the pubic tubercle to end in the midline (Fig. 7-22).

|

|

Figure 7-21

The ilioinguinal approach allows access to the anterior column and medial aspect of the acetabulum. It also allows visualization of the inner aspect of the pelvis from the sacroiliac joint to the symphysis pubis. |

|

|

Figure 7-22

Make a curved anterior incision beginning 5 cm above the anterior superior iliac spine. Extend the incision medially, passing just above the pubic tubercle to end in the midline. |

|

|

Figure 7-23 Dissect through subcutaneous fat in the line of the skin incision to expose the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle.

|

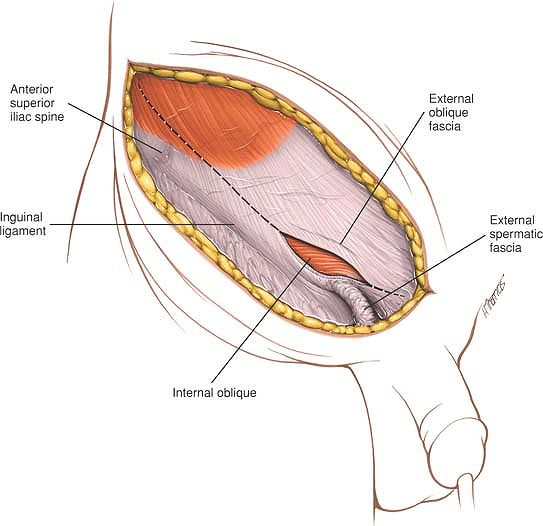

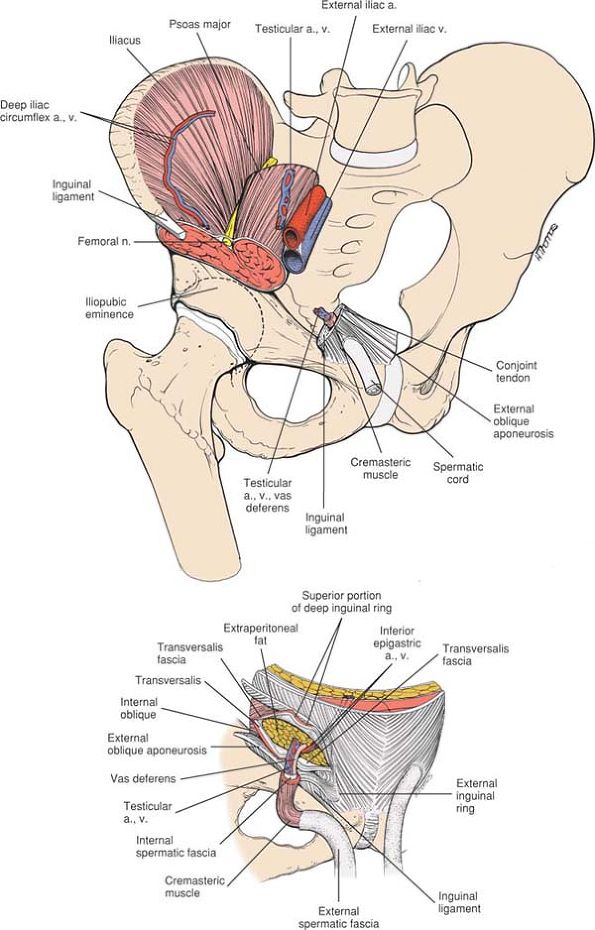

consists essentially of lifting off muscular, nervous, and vascular

structures from the inner wall of the pelvis.

The lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh will appear in the lateral

edge of the dissection. In most cases, the nerve will need to be

divided. Divide the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle in the

line of its fibers from the superficial inguinal ring to the anterior

superior iliac spine (Fig. 7-24). This will

expose the spermatic cord in the male and the round ligament in the

female. Carefully isolate these structures in a sling (Fig. 7-25).

Continue the dissection medially, dividing the anterior part of the

rectus sheath to expose the underlying rectus abdominis muscle. Strip

the iliacus muscle from the inside of the wing of the ilium. Initially,

you will need to use sharp dissection, but once inside the pelvis, use

blunt dissection.

proximal to its insertion into the symphysis pubis. Using blunt

dissection, develop a plane between the back of the symphysis pubis and

the bladder. This space (the Cave of Retzius) is easily developed with

a finger.

transversus abdominus muscles that form the posterior wall of the

inguinal canal (Fig. 7-26). Take care when approaching the deep inguinal ring; the inferior epigastric artery and vein cross the posterior

wall of the canal at the medial edge of the deep inguinal ring and must

be ligated at that point. Inadvertent division of these structures

results in profuse hemorrhage that is difficult to control. Now divide

those fibers of the transversus abdominus and internal oblique muscles

that arise from the lateral half of the inguinal ligament (Fig. 7-27).

|

|

Figure 7-24 Divide the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle from the superficial inguinal ring to the anterior superior iliac spine.

|

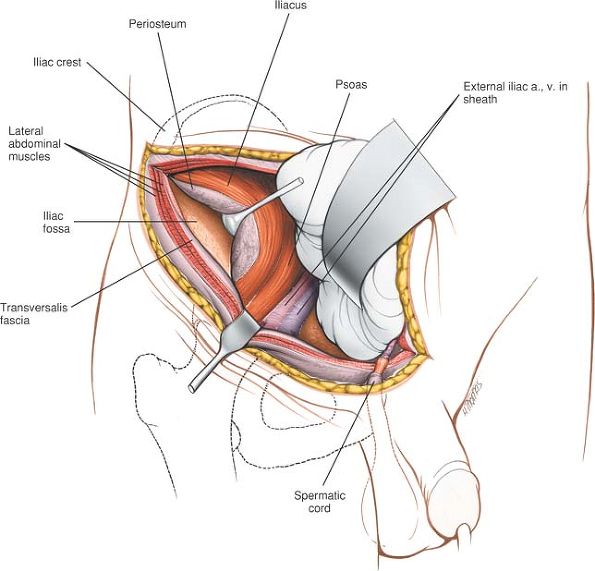

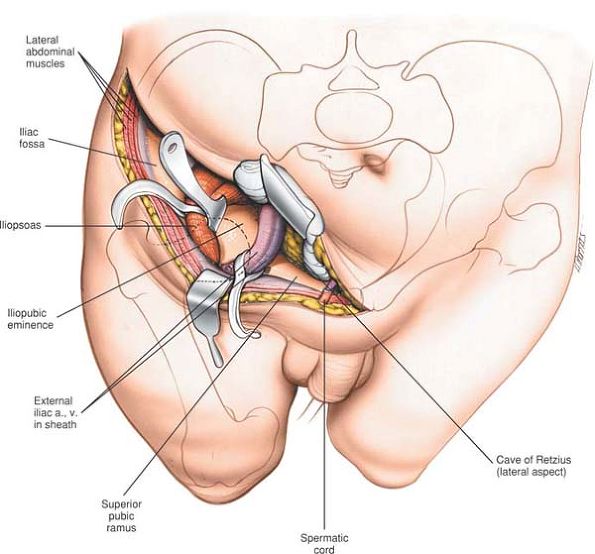

exposed. Using a swab, push the peritoneum upward to reveal the femoral

vessels, the femoral nerve, and the tendon of iliopsoas (Fig 7-28).

Isolate the femoral vessels together in the femoral sheath and protect

them with a sling. Pass a second sling around the tendon of iliopsoas

with the femoral nerve lying on top of it (Fig. 7-29).

Retract these structures either medially or laterally to gain access to

the underlying medial surface of the acetabulum and superior pubic

ramus (Fig. 7-30).

to the iliopsoas gives access to the inner surface of the ilium. The

middle window, medial to the iliopsoas but lateral to the femoral

artery and vein gives access to the quadrilateral plate. The medial

window, medial to the femoral artery and vein gives assess to the

superior pubic ramus and symphysis. For best visualization of the

medial window, the surgeon should move to stand on the opposite side of

the patient. Tilting the operating table also improves visualization of

the medial window.

beneath the inguinal canal lying on the iliopsoas muscle. Take care to

avoid vigorous retraction, as stretching the nerve will result in a

paralysis of the quadriceps muscle.

of the thigh will almost certainly have to be divided around the

anterior superior iliac spine at this stage of dissection. If it is

possible to retract it without compromising the exposure, do so.

Dividing the nerve will leave a patch of numbness on the outer side of

the thigh.

|

|

Figure 7-25 Mobilize the spermatic cord or round ligament in a sling. The posterior wall of the inguinal canal is now exposed.

|

pass beneath the inguinal ligament are surrounded by a funnel-shaped

fascial covering called the femoral sheath. It is this sheath that

should be mobilized and held between slings rather than dissecting out

the artery and vein separately. Care should be taken on retraction of

these structures to minimize the risk of deep vein thrombosis. The

femoral sheath contains the femoral artery and vein, and medial to the

vein is a space known as the femoral canal. The femoral canal contains

efferent lymph vessels, but also provides a dead space into which the

femoral vein can expand. This space can also, however, contain a

femoral hernia, and this should be remembered when mobilizing the

structure.

crosses the operative field passing medial to the deep inguinal ring.

It will need to be ligated to allow access to the deeper structures.

The inferior epigastric vein may be

damaged during dissection at the medial end of the approach. It is

usually avulsed from the side of the femoral vein. This causes a

profuse hemorrhage and requires the sewing of the resultant vascular

defect in the side of the vein.

the vas deferens and testicular artery. Although it is easily

mobilized, it must be treated gently during the approach and the

closure to avoid ischemic damage to the testicle.

mobilized off the back of the symphysis pubis. Be aware that fractures

of the lower half of the anterior column, especially displaced fracture

of the superior pubic rami, may have caused bladder damage and

adhesions.

|

|

Figure 7-26

Divide the rectus abdominal muscle 1 cm proximal to its insertion into the symphysis pubis. Divide the muscles forming the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. |

|

|

Figure 7-27

Ligate and divide the inferior epigastric vessels. Complete the division of the muscular structures of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. |

|

|

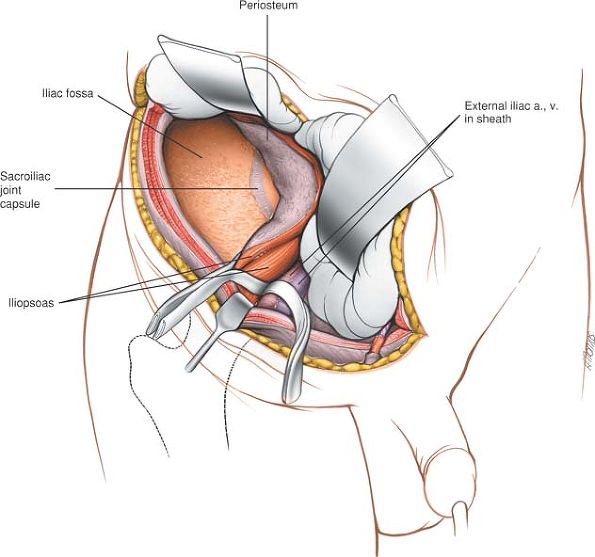

Figure 7-28

Using a swab, push the peritoneum upwards to reveal the femoral vessels. Mobilize the iliacus muscle from the inner aspect of the ilium. |

sacroiliac joint. Extend the skin incision posteriorly, following the

iliac crest. Using sharp dissection, cut down onto the bone. Then strip

off the origins of the iliacus from the inside of the ilium using blunt

dissection. Retract this iliacus medially to expose the inner wall of

the ilium and the sacroiliac joint (see Fig. 7-30).

|

|

Figure 7-29

Continue stripping off the iliacus from the inner wall of the ilium to reveal the sacroiliac joint. Pass the sling around the femoral sheath. |

|

|

Figure 7-30

Retract the iliopsoas and the femoral sheath either medially or laterally to reveal the medial surface of the acetabulum, the superior pubic ramus, and the inner surface of the ilium round to the sacroiliac joint. |

-

Lateral and posterior to the anterior superior iliac spine.

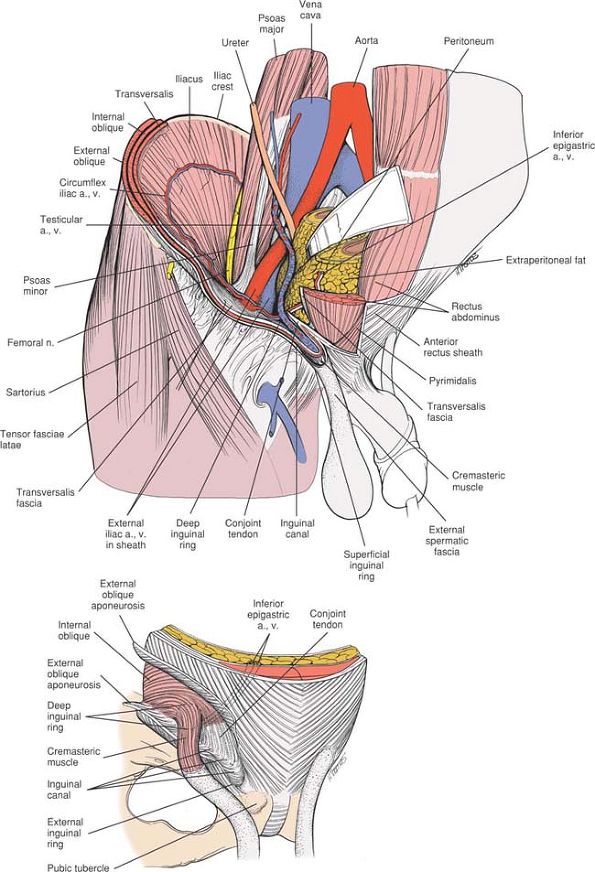

The dissection consists of detaching those muscles that arise from or

insert into the iliac crest and the inner wall of the ilium using

subperiosteal dissection. -

Medial and anterior to the anterior superior iliac spine.

The applied anatomy of the approach is that of the inguinal canal and

its related structures. Because pathology in this area nearly always

relates to herniae, both inguinal and femoral, it is usually an

unfamiliar ground for orthopaedic surgeons and, thus, is potentially

hazardous.

-

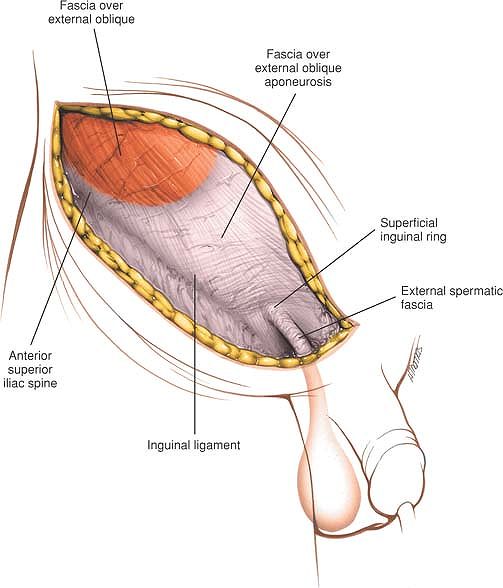

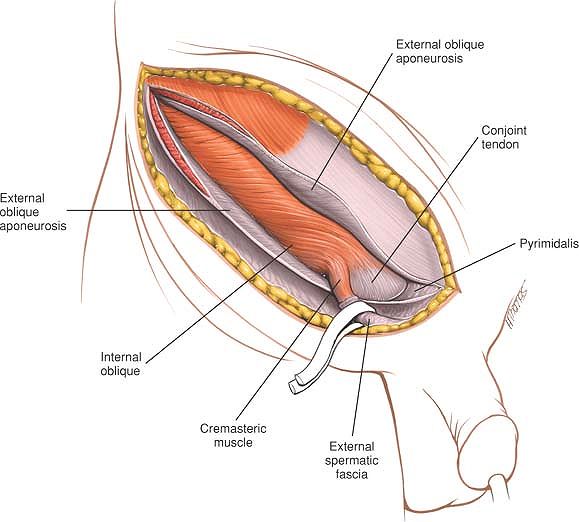

The external oblique

forms the outer layer of the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall. It

originates from the outer strip of the anterior half of the iliac crest. -

The internal oblique

forms the middle layer of the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall.

It originates from the center strip of the anterior half of the iliac

crest. -

The tensor fasciae latae arises from the outer lip of the anterior half of the iliac crest.

covered by the spermatic cord in the male and the round ligament in the

female.

cleavage in the skin. However, the extensive dissections involved may

leave rather broad scars. They are nearly always hidden by clothing.

which is the outer layer of the abdominal muscles, arises from the

lower eight ribs. It inserts as fleshy fibers into the anterior half of

the iliac crest. However, from the anterior superior iliac spine, it

becomes aponeurotic. The aponeurosis attaches to the pubic tubercle and

medially becomes fused with the aponeurosis of the opposite external

oblique muscle to form the anterior part of the rectus sheath.

Therefore, the splitting of the fibers of the external oblique muscle

and the incision of the anterior rectus sheath are both in the same

plane. There is a free lower border of this muscle between the anterior

superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. This free edge is called

the inguinal ligament. The aponeurosis curls back on itself to form a

gutter, and the free edge of this gutter is the origin of part of the

internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles.

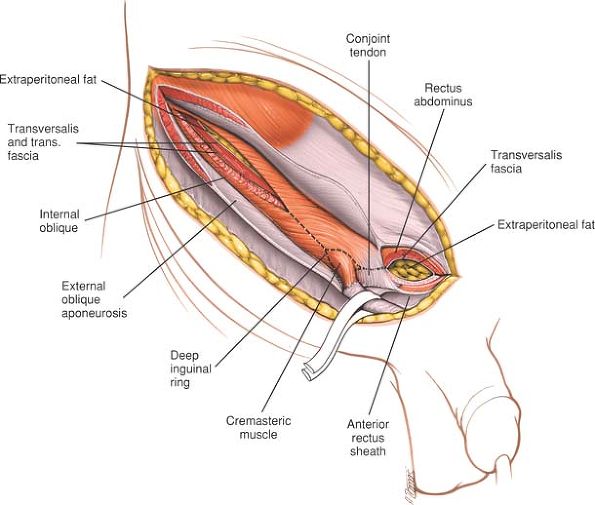

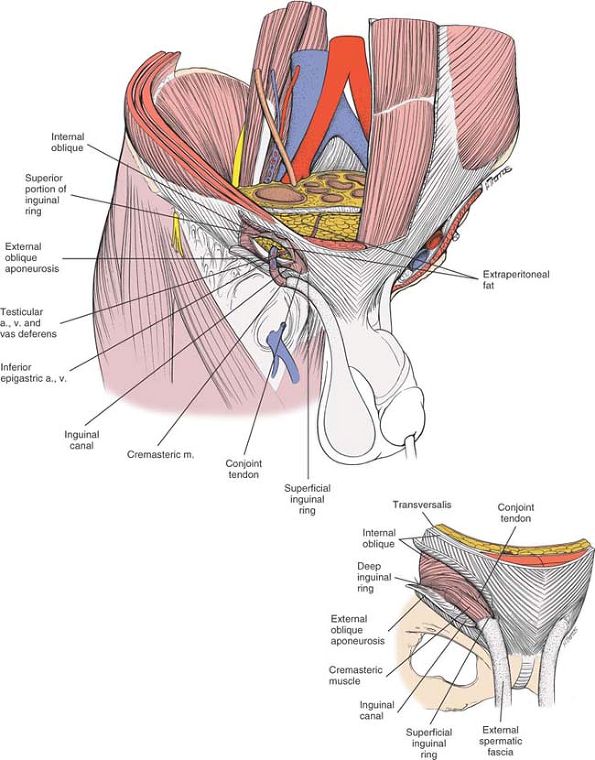

Dividing the fascia of the external oblique opens up the inguinal

canal, which is an oblique intramuscular slit running from the deep to

the superficial inguinal rings. These contain the spermatic cord in the

male and the round ligament in the female (Fig. 7-32).

fascia. In the region of this approach, however, the posterior layer of

fascia is inferiorly deficient. The anterior rectus sheath also

receives some tissue from both the internal oblique and transversus

abdominis muscles.

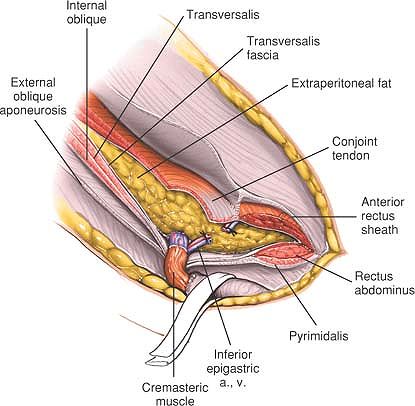

accompanied by its artery and the testicular artery and vein. As these

structures emerge through the abdominal wall, they get coverings from

each layer they pass through (Fig. 7-33). The

transversalis fascia covers the cord with a thin layer of tissue known

as the internal spermatic fascia. Passing through the transversus

abdominis and internal oblique, the cord gets covered with a layer of

muscle known as the cremasteric muscle. As it passes through the

external oblique at the superficial inguinal ring, it is covered by a

thin layer known as the external spermatic fascia. The round ligament

in the female is also covered by these three fascial layers. Both the

spermatic cord and round ligament can be mobilized easily in the

inguinal canal during the superficial surgical dissection.

|

|

Figure 7-31

The superficial musculature of the inguinal region. Just above the pubic tubercle, there is a gap in the aponeurosis of the external oblique to allow the passage of the spermatic cord in the male and the round ligament in the female. This gap is known as the superficial inguinal ring (inset). |

|

|

Figure 7-32

Dividing the external oblique muscle opens up in the inguinal canal. The spermatic cord is revealed covered by the cremasteric muscle, a muscle derived from the internal oblique muscle (inset). |

|

|

Figure 7-33

As the testis migrates out through the anterior abdominal wall in fetal development, it and its vas deferens get coverings from each layer they pass through. The external oblique provides the external spermatic fascia. The internal oblique provides the cremasteric muscle and the transversus abdominis provides the internal spermatic fascia. The cord is retracted to reveal the posterior wall of the inguinal canal formed by the conjoint tendons (inset). |

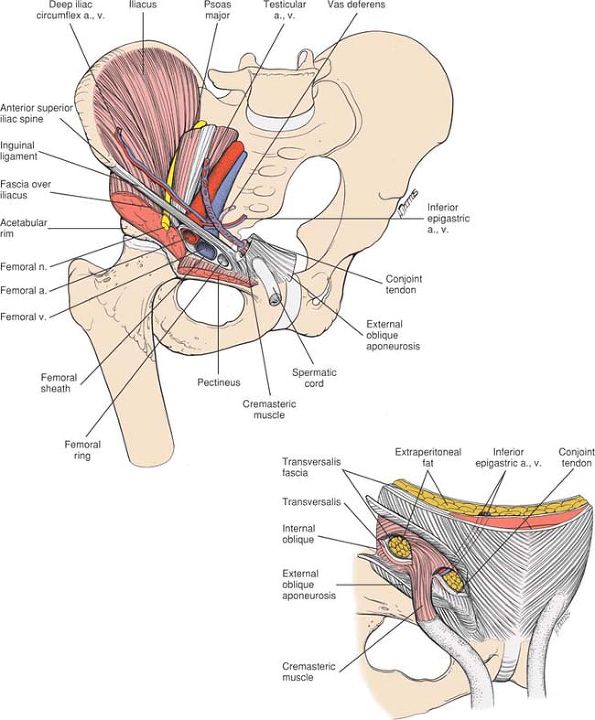

posterior wall of the inguinal canal is seen. In the lateral half of

the inguinal canal, the rolled free edge of the external oblique

aponeurosis gives origin to muscle fibers from both the internal

oblique and the transversus abdominis. These muscle fibers arch up over

the spermatic cord and fuse to form a conjoint tendon that is attached

posterior to the spermatic cord into the pubic crest. Therefore, in the

medial half of the inguinal canal, its posterior wall consists of this

conjoint tendon, which needs to be divided for access to the underlying

structures. The spermatic cord exits from the abdominal cavity through

the deep inguinal ring to enter the inguinal canal. Lateral to the deep

inguinal ring, fibers of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis

arise from the inguinal ligament and also have to be divided (see Fig. 7-33). Medial to the deep inguinal ring lies the inferior epigastric artery,

which usually requires ligation. Deep to these muscles lies the thin

transversalis fascia, extraperitoneal fat, and finally the peritoneum (Fig. 7-35).

inguinal canal. Careful repair of all these structures on a

layer-by-layer basis is important to prevent the development of an

inguinal hernia.

arises from the anterior aspect of the lumbar spine and passes into the

thigh below the middle of the inguinal ligament. Between these two

muscles, the femoral nerve runs down into the thigh. It is intimately

related to the iliopsoas and is mobilized with the muscle to avoid

excessive retraction. Medial to the nerve, the femoral artery and vein

enter the thigh. As these vessels leave the abdomen, they take with

them a fascial layer derived from the extraperitoneal fascia. This is

known as the femoral sheath. In addition to the artery and vein, the

femoral sheath has a space in it, medial to the vein, known as the

femoral canal. This is used for the passage of lymphatic vessels and

also allows the vein to expand at times when the blood return from the

leg becomes increased.

Because the femoral artery and vein are enclosed in a common fascial

sheath, they should be mobilized together. Separate mobilization of the

femoral vein will traumatize it, leading to possible thrombosis.

from the pubic bones by a space known as the Cave of Retzius. It is

occupied by very thin tissue, the bladder, and, in the case of the

male, the prostate. The prostate can be easily mobilized from the back

of the pubis. However, in cases of fracture, there may be pathologic

adhesions in this area, and great care should be taken not to

accidentally produce a bladder rupture. A full bladder will make safe

access to this area impossible, and a urinary catheter inserted

preoperatively is vital (Fig 7-36).

|

|

Figure 7-34

Deep to the inguinal ligament run the femoral nerve, the femoral vessel, as well as the psoas and iliacus muscles. Medial to the deep inguinal ring lies the inferior epigastric vessels (inset). |

|

|

Figure 7-35 Division of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal reveals the extraperitoneal fat.

|

|

|

Figure 7-36

The medial aspect of the acetabulum can be exposed by retraction of the iliopsoas and the femoral sheath. The inner aspect of the superior pubic ramus can only be visualized by careful mobilization of the bladder. |

It also allows direct visualization of the dorsocranial part of the

acetabulum, either through the fracture gap or via a capsulotomy. It is

by far the easiest of all acetabular approaches, and extensive blood

loss is not usually encountered. The approach does not allow access to

the anterior column. Its uses include reduction and fixation of:

-

Fractures of the posterior lip of the acetabulum

-

Fractures of the posterior column

-

Fractures of the posterior lip and posterior column

-

(Juxta- and infratectal) Simple transverse fractures

-

Transverse fractures with associated posterior lip fractures

used for fractures of the posterior lip and/or posterior column, place

the patient in the lateral position.

If traction is to be used, place a skeletal pin transversely through

the lower end of the femur with the knee flexed to reduce the risk of a

traction injury to the sciatic nerve.

|

|

Figure 7-37

The posterior approach to the acetabulum allows access to the posterior column, posterior lip, and dome segment of the acetabulum. |

natural tendency for the femoral head to move medially in cases of

transverse acetabular fracture. Operating in the lateral position,

therefore, makes reduction of these fractures more difficult. Reduction

of the fracture in this position can only be obtained by an assistant

lifting the femoral head out of the acetabulum. The use of the prone

position facilitates reduction of transverse fractures.

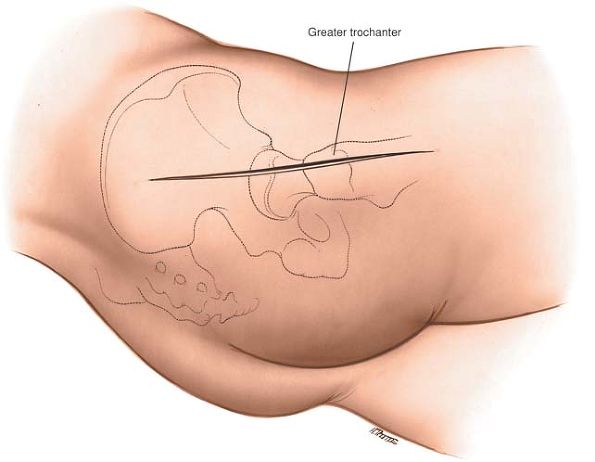

the thigh. Note that the posterior edge is easier to palpate than the

anterior one.

trochanter extending from just below the iliac crest to 10 cm below the

tip of the greater trochanter (Fig. 7-39).

|

|

Figure 7-38

Position of the patient for posterior approach to the acetabulum. Note the flexed position of the knee to prevent stretching of the sciatic nerve. |

|

|

Figure 7-39

Make a longitudinal incision centered on the greater trochanter extending from just below the iliac crest to 10 cm below the greater trochanter. |

|

|

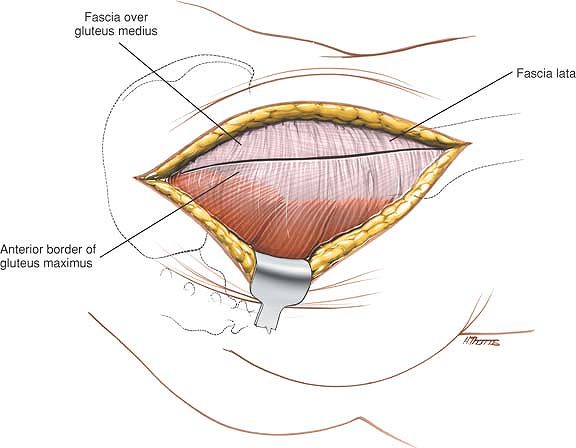

Figure 7-40

Incise the fascia lata in line with the skin incision. Extend the incision superiorly along the anterior border of the gluteus maximus muscle. |

However, the gluteus maximus that is split in the line of its fibers is

not significantly denervated because it receives its nerve supply well

proximal to the split.

fascia lata in the line of the skin incision in the lower half of the

wound, and extend this incision superiorly along the anterior border of

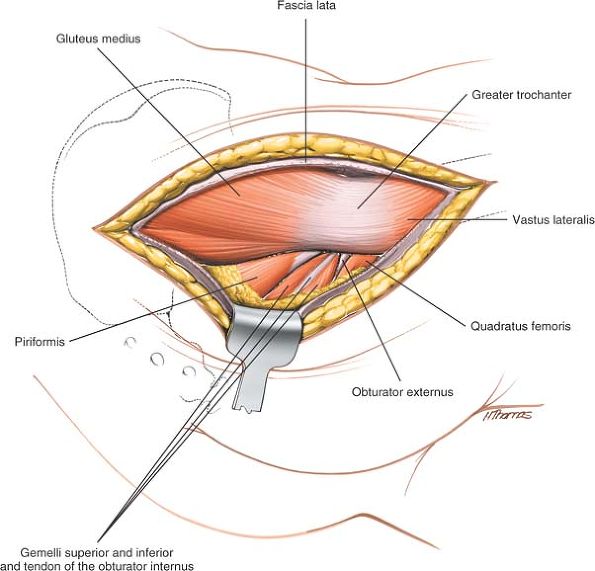

the gluteus maximus muscles (Fig. 7-40). Retract the split edges of the fascia to reveal the piriformis muscle and the short external rotators of the hip (Fig. 7-41). Partial detachment of the insertion of gluteus maximus from the femur will facilitate mobilization of this muscle.

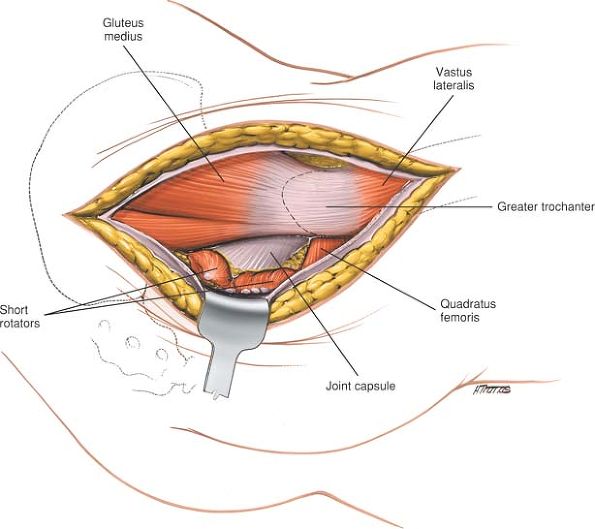

rotators and the piriformis on the stretch and detach these muscles as

they insert into the femur (Fig. 7-42). Using

the short external rotator muscles as a cushion, carefully insert a

retractor into the greater sciatic notch. Do not apply great pressure

on this retractor as this will create a sciatic nerve palsy. Insert a

second retractor into the lesser sciatic notch to expose the posterior

column in its whole extent.

often torn or detached in cases of trauma. If the posterior capsule is

intact and a direct inspection of the joint is required, make a

T-shaped capsulotomy. Ensure that you avoid damage to the limbus when

incising the capsule.

by distracting the femoral head. This can either be achieved by

skeletal traction or with the help of a Schanz screw placed in the

femoral head.

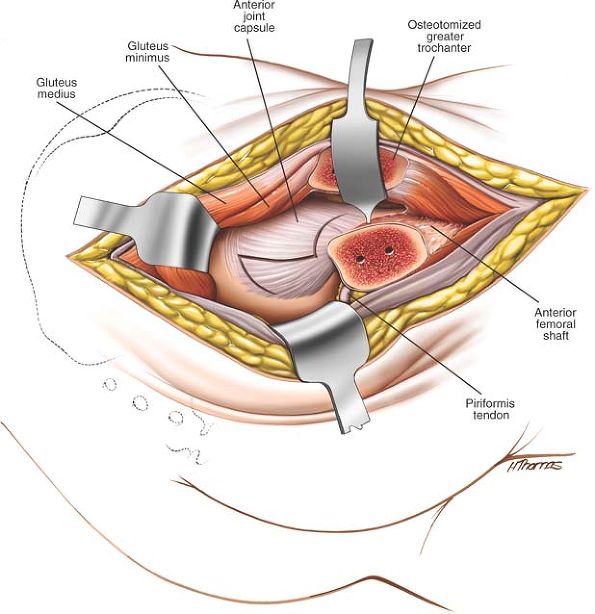

adequately visualized and fixed at this stage. If you require more

extensive exposure of the posterior column, perform an osteotomy of the

greater trochanter. Divide the greater trochanter from posterior to

anterior, removing a piece of bone 5 mm in size. This bone will have

the gluteal muscles attached to it superiorly and the vastus lateralis

attached to it inferiorly. Progressively evert the trochanter with its

attached muscles over the anterior surface of the femur using a sharp

retractor. The small remaining attachment of

gluteus

medius to the intertrochanteric ridge will now need to be released. If

difficulty is encountered mobilizing the fragment, the insertion of

piriformis may sometimes need to be partially released.

|

|

Figure 7-41 Retract the split edges of the fascia to reveal the piriformis muscle and the short external rotators of the hip.

|

joint capsule, flex and externally rotate the hip. Mobilize the

insertion of gluteus minimus from the retroacetabular surface along the

superior capsule to its femoral insertion along the anterior aspect of

the trochanter (Fig. 7-43). If further exposure

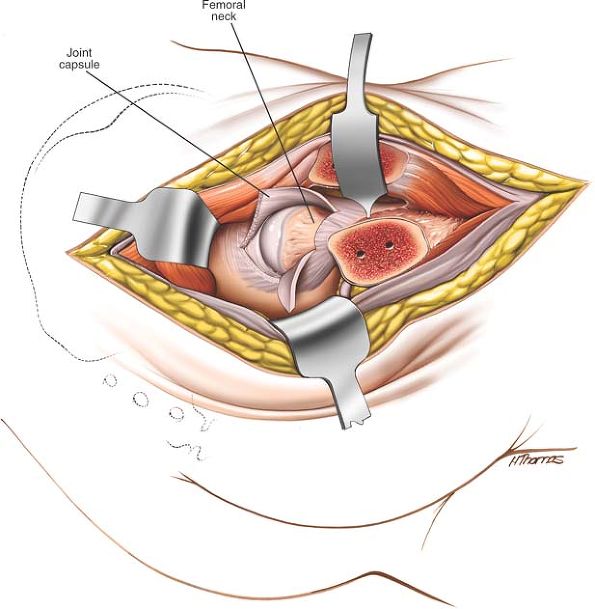

of the anterior capsule is required, mobilize the proximal portion of

the vastus intermedius from the femur to allow access to the anterior

hip joint capsule (Fig. 7-44). This

trochanteric fragment can be reattached easily with screws during

closure. Note that trochanteric osteotomies are associated with

heterotopic bone formation in acetabular surgery.

contused by the original trauma. Great care must be taken throughout

the operation that the nerve is not forcibly retracted. The divided

external rotators will protect the nerve from direct trauma, but the

nerve may still be injured by indirect forces transmitted through the

retractor. The nerve is in most danger if a fracture table with

continuous traction is used. You must be certain that the knee is

flexed to avoid stretching the nerve.

leaves the pelvis beneath the piriformis. This vessel may be damaged by

the original fracture or the artery may be injured during

the

surgical dissection. If the artery is transected, it will retract into

the pelvis and bleeding will be brisk. To control the bleeding, apply

direct pressure, then turn the patient over into the supine position.

If the artery has retracted into the pelvis, vascular control can only

be achieved by tying off the external iliac artery via a

retroperitoneal approach.

|

|

Figure 7-42 Divide the short external rotator muscles and the piriformis as they insert into the femur.

|

leaves the pelvis above the piriformis and enters the deep surface of

the gluteus medius. This attachment tethers the muscle, limiting the

amount of upward retraction of the muscle and prevents you from

reaching the iliac crest.

difficult because of the presence of an intact femoral head. In

addition to using longitudinal femoral traction, specialized femoral

head retractors are available that allow the head to be partially

dislocated, thereby facilitating clear visualization of the dome of the

acetabulum. It is critically important to obtain good visualization of

the inside of the joint because the screws used for internal fixation

may penetrate the joint.

level of the knee. Either split the vastus lateralis or elevate it from

the lateral intermuscular septum to allow exposure of the lateral

surface of the entire shaft of the femur.

|

|

Figure 7-43

For access to the anterior hip joint capsule, flex and externally rotate the hip. Mobilize the insertion of the gluteus medius from the retroacetabular surface. |

|

|

Figure 7-44

To complete exposure of the anterior capsule, mobilize the vastus intermedius from the femur. Perform a T-shaped capsulotomy of the anterior hip joint capsule to expose the femoral head and neck, together with the anterior lip of the acetabulum. |

KJ, Hoek van Dijke GA, Joosse P et al: External fixators for pelvic

fractures: comparison of the stiffness of the current systems. Acta

Orthop Scand 74:165, 2003

KA, Gautier E, Woo AK et al: Surgical dislocation of the femoral head

for joint debridement and accurate reduction of fractures of the

acetabulum. J Orthop Trauma 16:543, 2002

DC, Graney DO, Routt ML: Retropubic vascular hazards of the

ilioinguinal exposure: a cataveric and clinical study. J Orthop Trauma

10:156, 1996