Notochordal Tumors

Editors: Tornetta, Paul; Einhorn, Thomas A.; Damron, Timothy A.

Title: Oncology and Basic Science, 7th Edition

Copyright ©2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Section

II – Specific Bone Neoplasms and Simulators > 6 – Bone Sarcomas >

6.5 – Notochordal Tumors

II – Specific Bone Neoplasms and Simulators > 6 – Bone Sarcomas >

6.5 – Notochordal Tumors

6.5

Notochordal Tumors

Hannah D. Morgan

In human embryos, the notochord is a rod of cells on the

ventral aspect of the neural tube. It is the foundation of the spinal

column, as the vertebral segments are formed around it. In the adult,

notochord remnants form the nucleus pulposus of vertebral disks.

Chordomas are slow-growing malignant tumors of bone arising from the

remains of notochordal tissue almost exclusively in the axial skeleton

and exhibiting notochordal differentiation. There is frequently an

associated soft tissue mass, which most commonly extends anteriorly but

may have intraspinal extension as well. Chordomas are typically only

locally aggressive, but occasionally they do metastasize. Prompt

diagnosis of the tumor followed by complete surgical resection with or

without adjuvant radiation therapy offers the best clinical outcome.

ventral aspect of the neural tube. It is the foundation of the spinal

column, as the vertebral segments are formed around it. In the adult,

notochord remnants form the nucleus pulposus of vertebral disks.

Chordomas are slow-growing malignant tumors of bone arising from the

remains of notochordal tissue almost exclusively in the axial skeleton

and exhibiting notochordal differentiation. There is frequently an

associated soft tissue mass, which most commonly extends anteriorly but

may have intraspinal extension as well. Chordomas are typically only

locally aggressive, but occasionally they do metastasize. Prompt

diagnosis of the tumor followed by complete surgical resection with or

without adjuvant radiation therapy offers the best clinical outcome.

Pathogenesis

Etiology

Chordomas are low-grade malignant neoplasms of bone

arising from vestigial notochordal remnants that are almost exclusively

found in the midline of the sacrococcygeal, spheno-occipital (cranial),

and mobile spine regions.

arising from vestigial notochordal remnants that are almost exclusively

found in the midline of the sacrococcygeal, spheno-occipital (cranial),

and mobile spine regions.

Epidemiology

-

3% to 4% of primary bone tumors

-

Incidence rate in United States: 0.08 per 100,000

-

Male > female (male:female incidence rate 0.1–0.06 per 100,000)

-

Median age: 58 years; rare <40 years; extremely rare in first decade

-

Race: 91% Caucasian, 2% African-American, 7% other

-

Anatomic distribution: 30% to 50% sacral, 30% cranial, 15% to 30% spinal

-

Younger patients and females have propensity for cranial tumors.

-

Older patients more likely to have sacral site

Pathophysiology

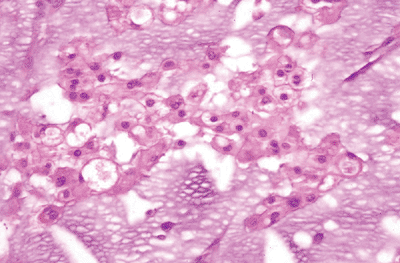

Chordomas are soft, grayish, lobular masses. They may

have gelatinous portions. They may cause expansion of the cortical

bone, and many have associated soft tissue masses. Histologically, the

tumors are composed of cords or nests of cells with vacuolated

cytoplasm. Mitoses are infrequent. The hallmark cells are physaliferous

cells (cells with bubbly cytoplasm surrounding the nucleus), although

they may be sparse or absent altogether. Occasionally there is

chondroid differentiation (Fig. 6.5-1).

have gelatinous portions. They may cause expansion of the cortical

bone, and many have associated soft tissue masses. Histologically, the

tumors are composed of cords or nests of cells with vacuolated

cytoplasm. Mitoses are infrequent. The hallmark cells are physaliferous

cells (cells with bubbly cytoplasm surrounding the nucleus), although

they may be sparse or absent altogether. Occasionally there is

chondroid differentiation (Fig. 6.5-1).

Classification

-

Grade and stage: most chordomas are low grade and localized

-

Rarely patients present with metastatic disease.

-

-

Variants: dedifferentiated and chondroid (skull base) described

Diagnosis

Physical Examination and History

Clinical Features

-

Pain and neurologic deficits are usual symptoms.

-

Delay in diagnosis of months to years common, due to chordoma’s slow growth and deep locations

-

Physical examination: thorough neurologic examination and rectal examination (for sacrococcygeal chordomas)

Radiologic Features

-

Plain radiographs

-

May show bony destruction but do not often characterize soft tissue extension

-

False-negative studies common

-

-

Computed tomography (CT)

-

Shows bony detail well; may demonstrate associated soft tissue mass

-

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

-

Tumors demonstrate low signal intensity

on T1-weighted and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images;

associated anterior soft tissue masses are well demonstrated. -

Shows lobular nature and midline location of tumor—aids in accurate diagnosis

-

Helpful in defining extent of tumor for adequate surgical planning

-

-

Bone scan

-

Sacral chordomas may show decreased tracer uptake, in contrast to many other sacral tumors.

-

-

Positron emission tomography (PET)

-

Metabolic imaging of tumor

-

(11)C-methionine (MET) PET imaging reported in literature; may help gauge effectiveness of treatment

-

Investigational

-

Diagnostic Work-up Algorithm

-

Same as for all aggressive bone lesions (see Chapter 1, Evaluation of Bone Tumors)

-

Avoid transrectal biopsies of sacrococcygeal masses!

Treatment

Surgical and Nonoperative Options

-

Wide surgical resection leads to a longer disease-free survival than nonoperative treatment or subtotal resection.

-

Radiation therapy improves disease-free

interval in patients with marginal or contaminated margins; can

typically be used only once.-

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy

(IMRT) and particle beam therapy offer promising alternatives to

conventional external-beam radiation therapy.

-

-

Chemotherapy ineffective

Preoperative Planning

-

Preoperative planning is essential to

properly counsel patient on risks of surgery (e.g., loss of bowel and

bladder function in high-level sacral chordomas) and to ensure that all

operative and reconstructive tools are available at the time of surgery. -

CT and/or MRI essential to determine extent of tumor

Surgical Goals and Approaches

-

Wide resection of tumor is the most successful treatment.

-

Surgical approach depends on tumor location.

-

Anteroposterior approach necessary for many chordomas of the mobile spine and sacrum

-

Some sacral tumors below S2 may be treated with posterior approach alone.

-

Techniques

-

Anterior approach, if needed, to free external iliac arteries from mass and begin tumor resection

-

Rarely colostomy needed

-

-

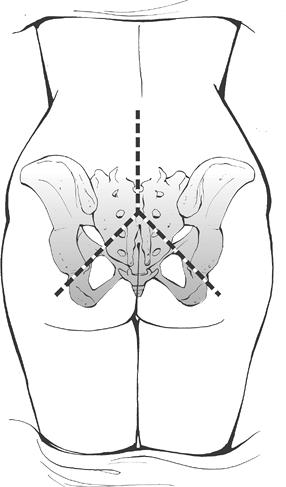

Posterior approach can be performed through three-limbed incision from lower back to both buttocks so wide exposure obtained (Fig. 6.5-2).

-

Ligation of dural sac above level of resection

-

If 50% or more of sacroiliac joint is intact, reconstruction is not needed.

![]() Figure 6.5-2 Sacrectomy incision.

Figure 6.5-2 Sacrectomy incision. -

If >50% of sacroiliac joint is

resected, stabilization of sacrospinal junction and pelvic ring is

recommended with instrumentation and bone grafting. -

Gluteal or rectus abdominis flaps or synthetic material may be needed to fill sacral defect.

-

Consider intraoperative or postoperative radiation therapy if resection margins are minimal or contaminated.

P.206

Complications

-

The rates of occurrence and types of

complications depend on the extent and location of tumor resection. The

most common complications are:-

Wound breakdown or deep infection

-

Bowel or urinary disturbance

-

Sexual dysfunction

-

Mobility impairment, especially with higher-level sacral tumors

-

Intraoperative blood loss

-

Oncologic problems (local recurrence or metastasis)

-

Results and Outcome

Oncologic Outcome

-

Depends on the location, size, and stage of the tumor, as well as the potential for complete resection

-

Local recurrence after surgery: up to 60% to 70%

-

Overall survival: 75% to 85% at 5 years, but drops to 40% to 50% at 10 years

-

Tumor-free margins and adjuvant radiation

therapy following the initial resection in patients with positive

margins increase the length of disease-free survival.

Functional Outcome

-

Function following resection also depends on the tumor location.

-

If both S3 nerve roots are preserved, bowel and bladder function is normal.

-

If both S2 nerve roots are resected, however, there is complete urinary and bowel incontinence.

-

Unilateral resection of S1, S2, S3 nerve

roots typically allows preservation of at least partial sphincter

function; however, unilateral sensory and motor deficits result.

Postoperative Management

The initial postoperative management is wound-related.

Drains are often left in the wound for over a week, and antibiotics are

continued while the drains remain. Dressings are changed frequently,

and if there is persistent wound drainage, the patient may require an

early incisional irrigation and débridement procedure. Patients who

undergo a resection that destabilizes the spine or spinosacral junction

may require postoperative bracing. If nerve roots above the level of S3

are resected with the tumor, early consultation with the physical

medicine and rehabilitation service for training in urinary

catheterization and bowel care protocol is recommended. Patients with

chordoma should undergo tumor surveillance with CT or MRI scanning of

the primary site as well as imaging of the lungs at routine intervals.

Radiographs of any spinal or pelvic instrumentation should also be

obtained.

Drains are often left in the wound for over a week, and antibiotics are

continued while the drains remain. Dressings are changed frequently,

and if there is persistent wound drainage, the patient may require an

early incisional irrigation and débridement procedure. Patients who

undergo a resection that destabilizes the spine or spinosacral junction

may require postoperative bracing. If nerve roots above the level of S3

are resected with the tumor, early consultation with the physical

medicine and rehabilitation service for training in urinary

catheterization and bowel care protocol is recommended. Patients with

chordoma should undergo tumor surveillance with CT or MRI scanning of

the primary site as well as imaging of the lungs at routine intervals.

Radiographs of any spinal or pelvic instrumentation should also be

obtained.

Suggested Reading

Cheng EY, Ozerdemoglu RA, Transfeldt EE, et al. Lumbosacral chordoma: prognostic factors and treatment. Spine 1999;24(16):1639–1645.

McMaster ML, Goldstein AM, Bromley CM, et al. Chordoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1973–1995. Cancer Causes Control 2001;12:1–11.

Ozaki T, Hillmann A, Winkelmann W. Surgical treatment of sacrococcygeal chordoma. J Surg Oncol 1997;64:274–279.

Sung MS, Lee GK, Kang HS, et al. Sacrococcygeal chordoma: MR imaging in 30 patients. Skeletal Radiol 2005;34:87–94.

York JE, Kaczaraj A, Abi-Said D, et al. Sacral chordoma: 40-year experience at a major cancer center. Neurosurgery 1999;44(1):74–79.