ARTHROPLASTY OF THE HAND

Hand, Upper Extremity, and Microvascular Surgery, Department of

Orthopaedics, Brown University School of Medicine, Rhode Island

Hospital, Providence, Rhode Island, 02903.

metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints is advanced painful destruction of the

joint by rheumatoid arthritis. The systemic effects of rheumatoid

arthritis on the metacarpophalangeal joints are mediated by the

formation of a pannus that is destructive to both the soft tissue and

bone. In patients without advanced bone destruction at the MCP joints,

intermediate procedures such as synovectomy and crossed intrinsic

transfers can be utilized to improve function and decrease pain,

although eventual progression and bony destruction will most commonly

occur. Patients who suffer from isolated posttraumatic arthritis of the

MCP joint, most commonly secondary to fracture, may also benefit from

arthroplasty; the increased demands of these generally younger patients

must be taken into account in assessing implant use, however. In

osteoarthritis, implant use is most satisfactory in nonborder digits

and in patients who will not accept joint fusion as a primary treatment

modality.

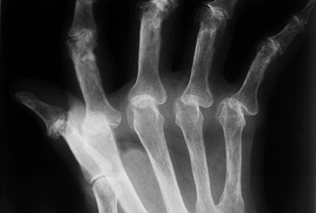

patient who presents with significant pain or severe destruction of the

MCP joints involving palmar subluxation of the proximal phalanx and

early fixed hyperextension deformity of the proximal interphalangeal

joint (Fig. 71.1) (20).

The concept of MCP joint implant arthroplasty was first reported in

1959, with goals to both relieve pain and correct deformity (5).

Since that time, a variety of implants have been developed and used for

MCP replacement, with improved durability in materials coming with

time. The primary prostheses used today are fashioned of silicone. The

major implants in use today are the original Swanson implant (Wright

Medical, Arlington, TN) (20), now used with

metal grommets in an attempt to prevent implant failure; the neutral

Avanta (Avanta, San Diego, CA) block design implant; and the newer

anatomically neutral NeuFlex (DePuy, Warsaw, IN) implant, designed to

decrease implant failure and improve functional arc of motion.

|

|

Figure 71.1.

Radiograph demonstrates severe palmar subluxation of the proximal phalanx on the metacarpal head resulting in pain and dorsal erosion of the proximal phalanx. |

extremity surgery. Functional status, lower extremity problems, and

level of pain are important issues prior to deciding whether or not

implant surgery should go forward. Many patients with rheumatoid

arthritis can function well with painless advanced deformities of the

joints of the hand, although deformity, despite being relatively

painless, should not be allowed to progress to a point where

arthroplasty becomes technically very difficult. In addition, the

status of the wrist also affects MCP arthroplasty outcome in that

uncorrected fixed radial deviation of the wrist in the face of MCP

joint replacement often leads to rapid recurrent ulnar drift and

implant failure at the MCP joints postoperatively. Most authors

advocate staged or simultaneous wrist fusion or arthroplasty to provide

a stable fulcrum for MCP joint arthroplasty in these patients (17).

In the majority of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, all four MCP

joints are generally replaced at a single setting. The thumb MCP joint

is generally not treated by implant arthroplasty due to the high forces

that occur during function, and the relative lack of disability

associated with fusion of the thumb MCP joint. In patients who have

significant disease at the thumb MCP joint, fusion of this joint can

frequently be undertaken simultaneously with implant arthroplasty of

the index through small-finger MCP joints.

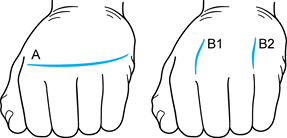

and increased level of function after MCP arthroplasty. The correction

of ulnar deviation (Fig. 71.2), improved

ability to perform activities of daily living, and improvement of

extensor lag have been documented in several outcome studies. Change in

range of motion has been variable, with some series reporting losses or

gains of up to 10° from preoperatively (4,11,14,16).

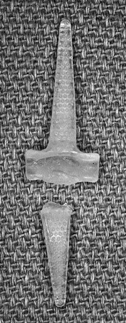

Until recently, the main objection to MCP joint arthroplasty has been

the inability to obtain full flexion postoperatively. Anatomically

neutral implants appear to allow improved functional flexion of the

digits without a significant increase in extensor lag, thereby

improving the overall arc of motion (Fig. 71.3).

In addition, in anatomically neutral implants the compressive and

tensile forces on the silicone is more evenly distributed through the

functional arc of motion. Nevertheless, no long-term data are available

on failure rates for anatomically neutral implants, and whether

theoretical improvements lead to clinical improvements remains to be

seen. All implants available in the United States and abroad have

initially been found to be satisfactory, but with long-term follow-up

they tend to fail.

|

|

Figure 71.2.

Ulnar deviation and an inability to extend the digits completely are fairly uniform in patients with longstanding rheumatoid arthritis. |

|

|

Figure 71.3.

The NeuFlex implant is a departure from prior designs as it undertakes an anatomically neutral axis to decrease implant forces and improve functional arc of motion for the patient. |

with one incision between the index and middle finger metacarpal heads

and the second between the ring and small finger metacarpal heads, or a

transverse incision at the level of

the MCP joints (A, Fig. 71.4A).

We favor the double longitudinal incision technique since postoperative

range of motion exercises do not cause tension on the wound; if wound

complications do occur, the implants are not directly exposed even in

cases of wound dehiscence.

|

|

Figure 71.4. The two types of incisions that can be utilized for metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty. See text for details.

|

-

Use a #15 blade to make a 5–6 cm

longitudinal incision from the finger web space proximally between the

index and middle finger and ring and small finger metacarpal heads. -

Utilizing curved dissecting scissors,

carefully dissect the subcutaneous tissues off the extensor tendon and

extensor hood of both MCP joints immediately adjacent to the surgical

incision. -

Utilizing a #15 blade, longitudinally incise the tight ulnar extensor hood.

-

Use a Hohmann retractor and scissors to completely radially sublux the extensor tendon and hood of both MCP joints (Fig. 71.5).

Figure 71.5.

Figure 71.5.

After longitudinally incising the ulnar extensor hood, the extensor

tendon and surrounding structures are subluxed radially, exposing the

metacarpophalangeal joint. -

The ring and small finger joints can also be exposed to allow sequential implantation of all implants in the same procedure.

-

Now prepare the metacarpal head and proximal phalanx to allow placement of the proper-size implant.

-

Protect tendinous structures using Hohmann retractors.

-

Using a microsagittal saw, transect the

MCP joint head at the distal metaphyseal flare (usually at the origin

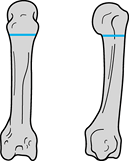

of the collateral ligaments) (Fig. 71.6).![]() Figure 71.6.

Figure 71.6.

Saw cuts at the distal flare of the metacarpal shaft just proximal to

the metacarpal head exposing the joint space for preparation. -

Use a rongeur to remove any sharp pieces

of bone and to debride any osteophytes present on the proximal phalanx

base. Do not osteotomize the proximal phalanx except in cases of severe

long-term subluxation, in which case remove some of the volar cortex to

allow appropriate spacing between the phalanx and the metacarpal.

broaching in both the metacarpal and phalangeal shafts. Use the

presized broaches to rasp the intramedullary canals to as large a size

as possible.

-

Use a sharp awl to place a starting hole in both the metacarpal and phalangeal shafts (Fig. 71.7).

Figure 71.7. A sharp awl is used to begin the starting hole in both the metacarpal and the phalangeal shafts.

Figure 71.7. A sharp awl is used to begin the starting hole in both the metacarpal and the phalangeal shafts. -

Perform a trial reduction using the trial implant size that corresponds to the last broach used (Fig. 71.8).

![]() Figure 71.8.

Figure 71.8.

Broaching should commence in progressively increasing sizes until the

broach can no longer be seated, followed by trial implant placement

with assessment of joint stability. -

Make sure that full flexion and extension

can be obtained without implant pistoning, excessive tightness or

laxity, or rotational deformity during motion. -

In the index finger, reconstruct the

proximally and radially detached collateral ligament through drill

holes in the metacarpal shaft to provide resistance for pinch. -

Then place the definitive implant and relocate the extensor tendon to the dorsal midline (Fig. 71.9 and Fig. 71.10).

If excessive shortening and palmar subluxation is noted, release of the

volar capsular structures may be required to get full flexion and

extension and implant stability. It is imperative to reconstruct the

radial extensor hood in an imbricated fashion to prevent recurrent

ulnar subluxation of the extensor tendon. Figure 71.9.

Figure 71.9.

Definitive correctly sized implant is placed in the metacarpal shaft

first, followed by placement in the phalangeal shaft. The implant

should rest appropriately between the metacarpal and proximal phalanx,

allowing full passive flexion and extension without restriction due to

soft-tissue structures.![]() Figure 71.10.

Figure 71.10.

Centralization of the extensor tendon may be accomplished by

imbricating the radial hood with horizontal mattress sutures after the

implant has been well seated. -

Use several horizontal 4-0 braided

nonabsorbable mattress sutures to reef the radial extensor hood in a

position to allow maintenance of the extensor tendon over the MCP joint

dorsally. -

Check to make sure that a full range of

motion occurs after reefing of the radial extensor hood without

excessive joint tightness or resubluxation of the extensor tendon. -

Irrigate the wounds and close the skin using 5-0 interrupted horizontal mattress sutures (Fig. 71.11).

Place a small drain in each of the wounds to prevent hematoma

formation, if necessary. Apply a bulky dressing with a volar plaster

splint that maintains all four fingers in full extension. Figure 71.11.

Figure 71.11.

The wounds are closed using interrupted 5-0 nylon sutures, taking care

to protect the skin edges with small drains, placed for 1 day

postoperatively to avoid hematoma formation. The patient is placed in a

full-extension splint with all the fingers included except the thumb.

The splint and dressing remain in place for 5 to 10 days

postoperatively (longer in patients who have had significant MCP joint

palmar subluxation and shortening preoperatively). Remove the drains

prior to hospital discharge. Remove sutures at the first postoperative

visit. Have the patient evaluated by a hand therapist and have a molded

full-extension pan splint placed as well as a dynamic extension splint

to allow early range of motion of the digits while maintaining the

extensor attitude of the MCP joints themselves (Fig. 71.12).

We recommend splints for the first 4 to 6 weeks, with gradual reduction

of their use by 2 to 3 months. In general, maximal functional range of

motion is obtained at 3 to 4 months postoperatively (Fig. 71.13). These basic principles and techniques

are germane to the use of all silicone arthroplasty implants available.

|

|

Figure 71.12.

A dynamic extension splint is helpful in maintaining metacarpophalangeal joint extension while allowing active flexion to occur in the postoperative rehabilitation period. |

|

|

Figure 71.13. Patient at 3 months after metacarpophalangeal arthroplasty. Anteroposterior radiograph (A) demonstrates excellent alignment of the MCP joints, with the ability to obtain full extension (B), and flexion at all metacarpophalangeal joints of 75° (C).

|

infection, prosthetic failure, recurrence of deformity, tendon

adhesions, and wound dehiscence. Implant fracture can be expected to

occur over time, although recent design changes may prolong implant

survival (Fig. 71.14). A recent report

utilizing the Avanta MCP joint arthroplasty demonstrated surprisingly

high fracture rates postoperatively at relatively early follow-up (2).

Fracture of the implant is a radiographic diagnosis and on occasion is

not clinically apparent, with patients maintaining some functional

range of motion (although generally decreased) with only minimal

increases in pain (11,16). Recurrence of deformity occurs after implant failure. Revision is not required unless symptoms warrant.

|

|

Figure 71.14.

A Swanson implant removed at revision metacarpophalangeal arthroplasty demonstrates implant failure at the stem–hinge interface (the most common site of implant failure with this design). |

Extensive soft-tissue release to balance the forces on the joint can

prevent recurrent ulnar deviation. Functional splints also help prevent

recurrent deformity during rehabilitation.

generally will require implant removal. Avoid wound dehiscence and

hematoma formations by using gentle and meticulous soft-tissue

technique.

to destruction by synovial proliferation as seen in the MCP joints in

rheumatoid arthritis. Painful PIP joints with loss of function are the

primary indication for replacement (21).

Advanced osteoarthritic destruction of the PIP joint can also produce

similar symptoms. PIP joint arthrosisin osteoarthritis is far more

commonly seen than at the MCP joint level (18).

Frequently, the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) is also involved in

this process. Although arthroplasty for the DIP joint has been reported

(2,3), results in

general have been less than satisfactory. Most surgeons recommend

fusion of the DIP joint by one of several methods as a definitive form

of treatment for painful deformities (3). PIP

joint arthroplasty for osteoarthritis, although not commonly performed,

is a treatment option after failed conservative therapy. Arthroplasty

of the PIP joints is best reserved for the nonborder digits, as is the

case with the MCP joints due to the high forces generated by pinch and

use of the hand (18). The same principles apply

to the rheumatoid patient, although in general deformity is far more

advanced and bone quality poor in the rheumatoid patient.

replacements similar to those used for the MCP joints as well as

various metal/high-density-polymer designs (3).

Recent reports have demonstrated excellent decrease in pain and

relatively good long-term durability with silicone implant arthroplasty

(1). Overall range of motion postoperatively,

however, has demonstrated mixed results, generally equaling the

preoperative abilities. Combining various metal/high-density-polymer

designs with the use of bone cement simulates a more anatomic

articulation; however, prosthetic loosening, fracture, and protrusion

through the cortex have been noted (15).

Nevertheless, the attractive anatomic contouring of these devices has

led several investigators to continue their development and refinement.

approach the PIP joint. We favor a dorsal approach although we have

used the volar approach quite successfully. Regardless of the approach

used, several basic principles, if followed, allow appropriate implant

placement and acceptable postoperative function.

-

Incise the extensor mechanism between the

central tendon and the lateral band so that no disruption of the

central slip attachment occurs (Fig. 71.15).![]() Figure 71.15.

Figure 71.15.

For proximal interphalangeal joint arthroplasty using the dorsal

approach, an incision between the central tendon and lateral band can

be performed so as not to disrupt the central slip, decreasing the

propensity for extensor lag postoperatively. -

Use a sagittal oscillating saw to resect

the proximal phalanx distal condyles at the end of the flare, allowing

exposure of the middle phalanx base. Use a rongeur to remove any

osteophytes present on either side of the joint. -

Enlarge the endosteal cavities by using a

small awl and then a dental burr followed by appropriate-size broaches

to prepare the canals.

adequate bone stock must be maintained to prevent osseous fracture, and

yet as large a size prosthesis as possible should be implanted. In

addition, the gap between the proximal and middle phalanx shafts needs

to be wide enough to allow placement of the implant. This may require

some additional bone resection at the base of the middle phalanx or

distal portion of the proximal phalanx. After appropriate broaching,

several steps need to be taken to ensure appropriate arthroplasty.

-

The trial prosthesis should have enough

give-and-take that both stems can be advanced without buckling during

flexion and extension of the finger. -

If any buckling or migration of the

implant occurs, either a smaller implant should be used or the bone

should be resected further to provide a larger gap. -

After the implant is placed, irrigate the

joint and repair the extensor tendon using figure-of-eight 4-0 braided

nonabsorbable sutures. Close the skin with horizontal mattress

interrupted 5-0 nylon sutures. Apply a light bulky dressing as well as

a volar splint holding the finger in full extension.

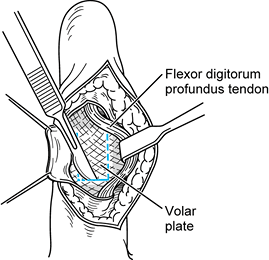

extensor mechanism is not compromised and postoperative extension does

not need to be maintained for as long (Fig. 71.16).

|

|

Figure 71.16.

The volar approach utilizes a standard Brunner skin-type incision, retraction of the flexor tendons, and proximal detachment of the volar plate, exposing the condyles of the distal proximal phalanx, which are then resected allowing implant placement and reconstruction of the volar plate through drill holes in the proximal phalanx. |

7 to 10 days, at which time the sutures are removed. Then fit a

removable Orthoplast splint to maintain the PIP joint in full extension

until 2 weeks after surgery, at which time gentle range-of-motion

exercises can begin. Use the extension splint between exercises to

prevent any extensor lag from occurring. If a volar approach is

utilized, less attention needs to be directed toward extension

splinting. With the volar approach, start early flexion as soon as

possible to prevent adhesions to the flexor tendons. Recurrence of

ulnar deviation (which is commonly seen preoperatively) can occur

following PIP joint arthroplasty. Splint training of the digit may be

required.

prosthetic failure. This complication may not be clinically significant

unless recurrent pain and significant deformity occur. Other

complications include prosthetic loosening, migration, and recurrence

of deviation deformity. Erosion of the prosthesis through delicate skin

can lead to disastrous results in rheumatoid patients. Gentle skin

retraction and care during the procedure is paramount. Infection is an

uncommon complication; if present, it generally requires implant

removal until well controlled.

joint is most often secondary to osteoarthritis. This clinical entity

is most commonly seen in postmenopausal women. Rheumatoid arthritis,

repetitive stress injury, and hormonally induced changes have also been

implicated as causes for basilar joint arthritis, but this occurs far

less frequently than degenerative osteoarthritis (17).

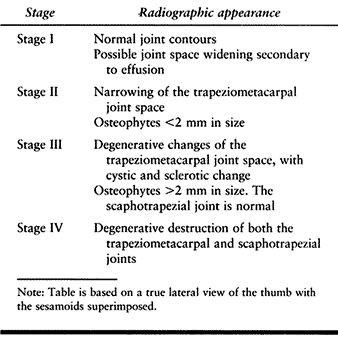

The extent of degenerative change in the CMC joint can be staged

radiographically according to the classification of Eaton and Littler (Table 71.1) (9).

|

|

Table 71.1. The Eaton-Littler Classification of Basal Joint Arthritis

|

conservative. A trial of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication and

hand-based splinting of the thumb CMC joint is often

successful

in early and moderate cases. In addition, an injection of

corticosteroid into the CMC joint can occasionally provide dramatic

pain relief and increased function in patients, although long-term

relief is not common. Some patients with extensive radiographic disease

have minimal pain, and others with minimal radiographic disease have

extensive pain; therefore, base treatment on the patient’s symptoms

rather than on the radiographs alone.

performed for painful thumb CMC arthritis. Silicone implantation to

replace the resected trapezium was developed by Swanson in 1968 (20).

Smaller silicone wafers utilized in a hemitrapezial excision have

provided excellent early symptomatic improvement, although silicone

synovitis resulting in pain and bony destruction has occurred in

long-term studies. As a result, silicone implantation of the thumb CMC

joint has been all but abandoned. Metal implants have recently been

advocated, although experience is limited and outcome uncertain (7).

Arthrodesis of the thumb CMC joint is a viable option and is useful in

younger, manual laborers who perform heavy work. It gives a predictable

painless result despite sacrificing some range of motion (17,19).

and tendon interposition or ligament reconstruction is most commonly

performed for arthroplasty of the thumb CMC joint (8).

In 1970, Froimson introduced the concept of using a ball of tendon as

an interpositional spacer between the carpus and thumb metacarpal after

excision of the trapezium (10). Due to the

potential for proximal migration of the thumb metacarpal, others have

advocated ligamentous reconstruction utilizing the flexor carpi

radialis tendon woven through the base of the thumb metacarpal (6). Outcome studies have not demonstrated that one technique provides substantially improved results over another (13). In fact, some authors have advocated excision of the trapezium alone without any interposition or reconstruction at all (12).

Having utilized both techniques, we currently favor excision of the

trapezium and tendon interposition without ligament reconstruction.

-

Make a 3.5 cm curvilinear incision dorsally over the thumb CMC joint.

-

Protect the sensory branch of the radial nerve as it passes over the capsule.

-

Incise the capsule longitudinally, exposing the trapezium.

-

Excise as much capsule off the trapezium

as possible and then use an osteotome and rongeur to morselize and

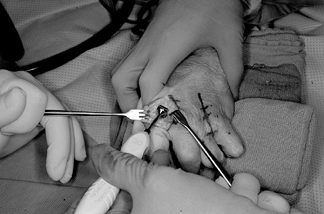

remove the trapezium (Fig. 71.17).![]() Figure 71.17.

Figure 71.17.

The trapezium, after exposure through a longitudinal capsular incision,

can be quartered with an osteotome and then removed piecemeal by a

rongeur. The trapezium is large; ensure that all pieces are removed

including any osteophytes or loose bodies present at the junction of

the bases of the first and second metacarpals. -

Make sure that all osteophytes at the junction of the bases of the first and second metacarpals are removed.

-

Place a small osteotome between the bases

of the first and second metacarpal shafts and then transfix the thumb

metacarpal in appropriate alignment by using a 0.045 Kirschner wire

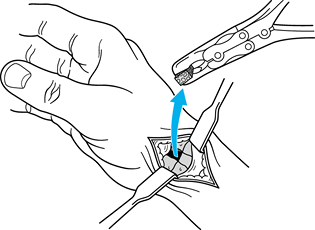

passed from the first metacarpal into the second metacarpal (Fig. 71.18). Figure 71.18.

Figure 71.18.

A postoperative radiograph demonstrates fixation of the thumb

metacarpal “in space” to the index metacarpal via a single Kirschner

wire with the distraction between the bases allowing soft-tissue

interpositional ingrowth. Note the space where the trapezium has been

excised and a soft-tissue tendon interposition performed. The Kirschner

wire is generally left in for 4 weeks, after which it is removed and

the cast discontinued to begin therapy. -

Now, make a transverse 1 cm incision over the palmaris longus at the wrist.

-

After identifying the palmaris longus, use a Brand tendon stripper to harvest the palmaris longus and close the skin wound.

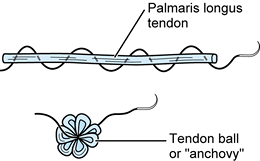

-

Form a tendon ball or “anchovy” with the palmaris longus tendon using a braided 4-0 nonabsorbable suture (Fig. 71.19).

![]() Figure 71.19.

Figure 71.19.

Using a 4-0 nonabsorbable suture passed in a back-and-forth fashion

through a free tendon graft (most commonly, the palmaris longus),

sewing the suture onto itself, a tendon ball or “anchovy” can be

fashioned and placed in the interposed position. -

Place the tendon anchovy beneath the distal-most portion of the flexor radialis tendon at the floor of the excised trapezium.

-

Suture the anchovy so that it is fully interposed between the first and second metacarpal bases.

-

Close the CMC capsule carefully, using interrupted absorbable sutures.

-

Leave the Kirschner wires exposed outside the skin.

-

Apply a large bulky dressing including a thumb spica splint that allows interphalangeal joint motion.

postoperatively, then remove the sutures. Apply a below-elbow thumb

spica cast allowing interphalangeal thumb motion and full MCP motion of

the other digits. Maintain the cast for 4 weeks. Then remove the

Kirschner wire in the office and place the patient in a removable

Orthoplast splint. Begin hand therapy at 4 weeks with gradually

increasing range-of-motion and strengthening exercises. Four weeks of

therapy is usually required.

Avoid infection by administering intravenous antibiotics during the

procedure. Patients undergoing thumb CMC arthroplasty can have

significant swelling postoperatively. Avoid tight dressings.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.

CR, Hansraj KK, Todd AO, et al. Swanson Proximal Interphalangeal Joint

Arthroplasty in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin Orthop 1997;342:34.

RI, Pellegrini VD. Surgical Management of Basal Joint Arthritis of the

Thumb. Part II. Ligament Reconstruction with Tendon Interposition

Arthroplasty. J Hand Surg [Am] 1986;11:324.

RG, Glickel SZ, Littler JW. Tendon Interposition Arthroplasty for

Degenerative Arthritis of the Trapeziometacarpal Joint of the Thumb. J Hand Surg [AM] 1985;10:645.

H, Stetson W, Brumfield RH, et al. Silastic Metacarpophalangeal Joint

Arthroplasty in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin Orthop 1997;342:16.

KK, Ashworth CR, Ebramzadeh E, et al. Swanson Metacarpophalangeal Joint

Arthroplasty in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin Orthop 1997;342:11.

RL, Murray PM, Vidal M-A, Beckenbaugh RD. Development of a Surface

Replacement Arthroplasty for Proximal Interphalangeal Joints. J Hand Surg [AM] 1997;22:286.

AB, Maupin BK, Gajjar NV, de Groot Swanson G. Flexible Implant

Arthroplasty in the Proximal Interphalangeal Joint of the Hand. J Hand Surg [AM] 1985;10:796.