SURGERY OF THE THORACIC OUTLET

result from compression of the neurovascular structures as they exit

the chest and neck and pass through the costoclavicular interval and

down into the axilla. The clinical presentation in each patient

reflects the degree of compression of the brachial plexus and of the

subclavian artery and vein. Historically, the interscalene area was

considered the primary site of compression, but subsequent experience

has shown that treatment of this disorder requires understanding the

dynamic anatomy of the entire region of the neck and shoulder region.

normal development, age, and disease complicate the problem

considerably but also provide a way to understand how signs and

symptoms are produced (39). Specifically,

exaggeration of the normal caudad descent of the shoulder girdle

produced by poor posture or local injury can cause compression of the

lower trunk of the brachial plexus and of the subclavian artery and

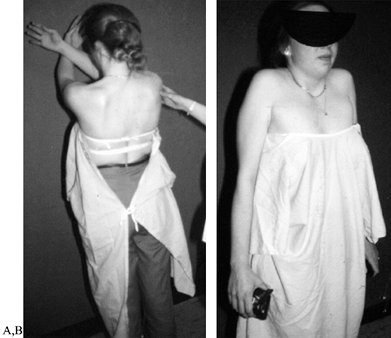

vein (Fig. 61.1). This mechanism can explain the emergence of symptoms of TOS in patients who are asymptomatic before motor vehicle accidents (6,20,26).

Congenital anatomic abnormalities such as cervical ribs, long

transverse processes, or congenital bands can increase the severity of

the effect.

|

|

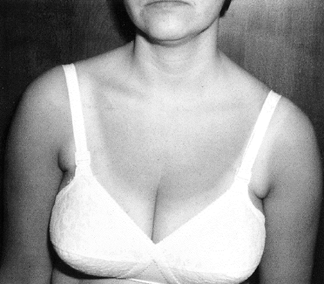

Figure 61.1.

This patient was asymptomatic before a motor vehicle accident in which she sustained what was termed a whiplash injury. This caused pain in the shoulder girdle, which led to a postural droop of her scapula and subsequent thoracic outlet compression. She was overweight with large breasts, which added to the downward pull on her shoulder girdle. Ultimately, after failure of conservative treatment, she underwent first rib resection with relief of her symptoms but required extensive postoperative muscle reeducation to correct her posture. |

population has been reported in different studies to range from 0.056%

to l.5% (35), nine types of congenital fibrous

bands have been described that can cause neurovascular compression

within the thoracic outlet (30). Malunions and nonunions of the clavicle can also lead to thoracic outlet compression (14). Instability of the glenohumeral joint (33) can be associated with numbness and tingling within the limb or with secondary TOS (17).

with TOS outnumber males by about four to one. The disorder is seen

most commonly between puberty and the

fourth

decade of life. Although there are scattered case reports of girls who

have developed TOS in childhood, the authors do not report whether the

patients had attained menarche. A postmenopausal woman who develops

symptoms thought to be due to thoracic outlet compression should be

carefully examined to be certain that the symptoms are not due to

another condition.

chapter, I believe that the diagnosis of TOS is primarily clinical.

Although some laboratory examinations are helpful, diagnosis is usually

made on the basis of a careful history and physical examination.

which structures are being compressed. The majority of patients

complain of pain and paresthesias that radiate from the neck, upper

chest, or shoulder region, down the medial aspect of the arm and into

the little and ring fingers, although some experience numbness of the

entire upper limb. Much less commonly, it is the radial aspect of the

arm and hand that is numb. Symptoms are often nocturnal; elevation of

the arm in sleep or during activities aggravates them. Complaints such

as the inability to hold a hair dryer or to work with the arms above

the head are common. Some patients have numbness when driving or when

carrying heavy objects. These symptoms are caused by compression of the

lower trunk of the brachial plexus.

weakness of the ulnar-innervated intrinsic muscles unless compression

is severe. There may be weakness of all the intrinsic musculature and

loss of power of the long flexors of the little and ring fingers. When

the upper trunk of the brachial plexus is involved, differential

diagnosis becomes more difficult, and there may be confusion with

cervical radiculopathy or carpal tunnel syndrome.

insufficiency or gangrene in the hand, but such severe symptoms are

rarely seen in an orthopaedic practice. Such patients usually have

acute occlusion of the subclavian or axillary arteries and often have

aneurysms caused by compression by significant cervical ribs (13,27). This complication is more often found in older patients with long histories of often undiagnosed symptoms.

upper limb, which, if intermittent, is difficult to document until its

severity motivates the patient to have it examined. Intermittent venous

compression in the absence of thrombosis produces cyanosis as well as

swelling in the limb.

This “effort thrombosis” of the subclavian and axillary veins results

from underlying subclinical thoracic outlet compression and repetitive

or strenuous use of the arms, particularly in the overhead position.

The symptoms are acute pain and swelling of the limb and ipsilateral

chest wall. Prompt recognition of the condition is imperative—delay may

result in considerable disability due to chronic pain and swelling.

Acute therapy consists of administration of intravenous thrombolytics

by catheter, with mechanical dilatation, if needed. Maintain the

patient on anticoagulants for 3 or 4 months, and follow up with

elective first rib resection to diminish the likelihood of recurrent

thrombosis (35).

diagnosed as being consistent with TOS. In this case, it is attributed

to selective compression of the sympathetic innervation of the limb

within the lower trunk of the brachial plexus. The etiology of

unilateral Raynaud’s phenomenon is not collagen disease. More likely,

this phenomenon represents episodes of distal embolization from an

aneurysm located within the subclavian artery (13).

pain. When TOS is in the left hemithorax, such pain may mimic angina or

myocardial infarction and bring the patient repeatedly to the emergency

room or cardiac care unit (42).

achieve a positive diagnosis but also to rule out other conditions that

may be confused with TOS or that may coexist with it. Cervical

radiculopathy is unusual in the C8—T1 distribution in the arm and hand (5).

Nevertheless, when the symptoms are difficult to interpret, the

cervical spine must be ruled out as a site of disease. There may be

tenderness over the brachial plexus in the supraclavicular fossa, but

this nonspecific finding may accompany either thoracic outlet

compression or cervical radiculopathy.

thoracic outlet compression, the overhead exercise test and Wright’s

maneuver (49) are the most consistently

positive. The first test is performed by having the patient, in the

“hands-up” position, rapidly flex and extend the fingers. In

susceptible patients, this exercise produces cramping on the affected

side within 30 seconds. In addition, placing the arm in the abducted

and laterally rotated position not only obliterates the pulse at the

wrist but also reproduces the symptoms. Lowering the arm to the side

restores the pulse and alleviates the symptoms.

provocative positions is not diagnostic of TOS, because in many young

women, some position of the arm can obliterate a pulse. The

reproduction of the symptoms is crucial! Sometimes they can be elicited

by rotating the neck to the opposite side or by having the patient take

a deep breath, particularly while the affected extremity is abducted

and externally rotated at the shoulder.

reproduces symptoms in patients whose costoclavicular interval has been

narrowed, particularly by a clavicular fracture. The classic Adson’s

maneuver is performed by having the patient, with the arm dependent,

rotate and hyperextend the neck to the affected side and take a deep

breath. In my experience, this has been the least rewarding of the

provocative tests.

to verify the stability of the glenohumeral joint, because patients

with instability may complain that the arm “feels dead” (33).

In addition, finding an increased venous pattern on the side of the

lesion is presumptive evidence of venous hypertension and possible

compression or thrombosis.

of the hand. The only motor deficit may be just-perceptible atrophy of

the hypothenar muscles and weakness of adduction of the little finger

to the ring finger. Rarely, all of the intrinsics are weak or atrophic.

The cutaneous distribution of the first thoracic nerve is the medial

aspect of the forearm, thus it is differentiated from the distribution

of the ulnar nerve.

to assess the lower cervical spine for the presence of adventitious

ribs or long transverse processes at C7 because the patient’s

identification plate may have been placed there. Hypoplastic, true

first ribs may be present, and sometimes, a cervical rib can be

confused with a hypoplastic rib unless you are sure of the vertebral

level. Count from the atlas caudalward to establish that there is, in

fact, a cervical rib. Look carefully at the disc spaces and the

intervertebral foramina, and note abnormalities. In the lateral view of

patients with droopy shoulders, the physician may be able to clearly

define the second dorsal vertebra. Such patients may resemble those

with TOS but may have no peripheral neural deficits in the limbs (37).

lung tumors, which can mimic TOS in their presentation. Adequate

radiographs of the shoulder are also necessary. When there is

significant concern about possible cervical radiculopathy, magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) or myelography may be indicated. They are not

needed in most cases.

reliable diagnostic test for TOS. In my experience, however, because

pulses can be positionally obliterated in many normal people, the

incidence of false-positive results is substantial. Interpret such

studies with caution. For patients with intrinsic vascular disease,

noninvasive studies can be extremely useful.

the general diagnosis of TOS, and I do not routinely use them. Because

the occlusion of arterial outflow with the position of the arm may be

observed in asymptomatic patients, an arteriogram would provide little

information unless there is serious consideration of the presence of an

aneurysm in the subclavian artery or intrinsic vascular disease.

Patients with complete cervical ribs may have an increased incidence of

such aneurysms (13,27).

Therefore, in such patients, it is prudent to obtain arteriographic

studies if the surgeon intends to explore the thoracic outlet through

the axilla. Venography is useful in demonstrating thrombosis of the

axillary or subclavian vein and in following the process of

recanalization, should it occur. Noninvasive testing may be of value in

this situation as well.

the velocity of conduction of the ulnar nerve through the thoracic

outlet to diagnose TOS, the experience of many workers has failed to

substantiate this claim (40,42,44).

Reports from electrodiagnostic laboratories may say, “There is no

evidence of TOS”; interpret such statements based on nerve conduction

velocity (NCV) with caution, however, because the test is not of value

in this situation.

Conditions such as ulnar neuropathy at the elbow and carpal tunnel

syndrome are readily identified by means of

NCV

determinations. Because NCV determination is not a reliable means of

assessing the plexus within the thoracic outlet, the use of

somatosensory evoked potentials and F responses has received attention

as a means of obtaining further objective evidence of neural

dysfunction to diagnose TOS (10,23).

Some workers have found the measurement of the amplitude of the evoked

response of the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm and C8 root

stimulation to be of value in making the diagnosis (24).

In my opinion, the diagnostic value of such measurements has not yet

been firmly established, and the diagnosis remains clinical (4,44).

usually not markedly abnormal unless there has been sufficient

compression to cause denervation. In such cases, it is often possible

clinically to detect atrophy and weakness of the ulnar-innervated

interosseous and hypothenar muscles. In other patients, however, these

muscles may show fibrillation potentials at rest that appear to be

clinically normal (36).

have written that the coexistence of TOS and carpal tunnel syndrome is

rare if it exists at all, patients are seen nonetheless with

well-demonstrated signs of both entities (47). Ulnar neuropathy may coexist with TOS (16).

Patients may have hard-to-define combinations of signs and symptoms

that appear to be the result of more than TOS. I these cases, look for

additional lesions to explain the entire picture; otherwise treatment

will fail.

enormously, and in many cases, the symptoms have been present for

months or years. Not uncommonly, such patients have been told that

their symptoms are of emotional origin, or they have been subjected to

unsuccessful conservative or operative treatment. Such patients require

objective, sympathetic evaluation and sometimes psychological

consultation. Some patients with TOS are clinically depressed. The very

deleterious effect depression has on their posture aggravates the

anatomic problem. If such is the case, the surgeon may, according to

training and inclination, treat the patient with antidepressants or

refer him or her for psychotherapy. It is not rare to see patients

whose symptoms of TOS can be lessened by such measures, even though

some may ultimately require surgery.

often poor. It is worthwhile to inquire about their level of physical

activity; often, it is quite limited. Sometimes, patients are afraid to

exercise for fear of worsening the condition, or they have been so

advised by their physicians. If the patients have no other serious

medical problems, make an effort to mobilize them with aerobic

exercises. Probably the easiest generalized exercise for such patients

is walking, because it does not usually cause much discomfort. Some

patients may experience increased symptoms with walking, and in these

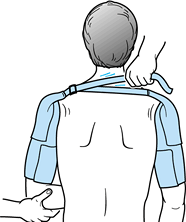

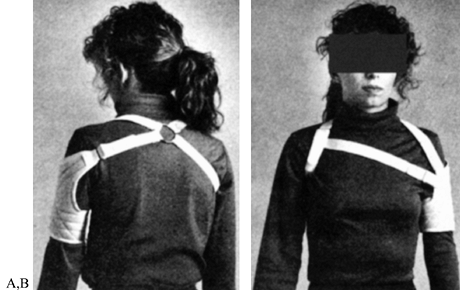

cases, the use of a shoulder support such as the Biomet Hook

Hemi-Harness (Biomet, Warsaw, IN) (Fig. 61.2) or the Roylan sling (Smith & Nephew, Germantown, WI) (Fig. 61.3) may help. Also, such patients may be able to benefit from use of a stationary bicycle.

|

|

Figure 61.2.

The Biomet Hook Hemi-Harness as seen from behind is shown. It consists of two cloth sleeves with Velcro closures and an adjustable strap that can be tightened or loosened as needed to support the shoulder girdles. In addition to the height of the shoulders, the degree of retropulsion is determined by where the strap is attached to the sleeves, and this, too, may be varied according to the correction required. |

|

|

Figure 61.3. The Roylan sling as seen from the back (A) and the front (B).

|

manage; patients do not like to be told that they are overweight. Yet,

excess soft tissue can place additional strain on the shoulders,

particularly in women who have large breasts, which can aggravate TOS

by increasing traction on the structures crossing the first rib. In

cases of gigantomastia, reduction mammoplasty as a first step in the

treatment of very debilitating TOS may be successful. Kay has reported

on neurologic deficits in women with large breasts (15).

The mechanism of thoracic outlet compression makes it likely that this

is the locus of the problem. Even if weight reduction does not produce

the desired alleviation of compression, the patient who is thinner will

be easier and safer to operate on, especially through the axilla.

of TOS involves correcting postural abnormalities that can be

identified as contributing to the compression, and exercises to

strengthen the shoulder girdle when it is determined that weakened

muscles are a significant factor (Fig. 61.4).

Unfortunately, when the physician refers patients with TOS to a

physical therapy department, it is not always guaranteed that the

therapist caring for the

patient will understand the genesis of the problem and apply appropriate therapy. Very often, stereotyped routines (25)

such as stretching, soft-tissue massage, “nerve mobilization,” and

cervical traction are used, and these methods will actually worsen the

symptoms in many patients. The TOS patient must have a thorough

analysis by a knowledgeable therapist, and an individual therapy

program should be designed, implemented, and monitored to avoid

provocative maneuvers (25).

|

|

Figure 61.4. A:

The therapist is instructing the patient in the correct way to exercise. Note that the arms are held in front of the plane of the body and that they are below shoulder height. The trapezius, rhomboids, and levator scapulae can be strengthened in this way without bracing the shoulders back or provoking symptoms. The therapeutic plan must be individualized to the specific patient’s needs, and most often it can be carried out as a home program with occasional visits to the therapist. B: Exercises for the upper trapezius that are tolerated by most patients with TOS. |

not tolerate even the most gentle conservative program. Particularly in

the case of anterior glenohumeral instability, the exercises often

prove provocative because they tend to reproduce the subluxations. Such

patients may be differentiated from those with dead arm syndrome. In

all likelihood, many patients with the diagnosis of dead arm syndrome

owing to glenohumeral instability really have TOS. If the condition

goes unrecognized, the patients will

continue

to be symptomatic even after shoulder repair. Leffert and Gumley

studied an interesting series of patients in whom these two entities

coexisted (17).

related to symptoms of TOS, modify such activities, if possible.

Overhead activities, the carrying of heavy loads, or the use of

backpacks can be quite provocative to patients with compression within

the thoracic outlet.

periodically so that the condition does not drag on interminably. The

conservative approach with periodic review is particularly important in

patients whose cases are complicated by litigation, insurance, or open

workers’ compensation cases. Caregivers must try to be objective in

interpreting symptoms so that patients are not unfairly deprived of the

benefits of treatment. In addition to periodic reviews, set a time

limit beyond which conservative therapy should be viewed as having

failed. If there is no positive response, the clinician must decide

whether to advise surgery or to accept the status quo with hopes that

the condition may improve with time.

the previously described treatment measures is the usual indication for

surgery.

the intrinsic muscles of the hand but sometimes in the long flexors as

well—almost never respond positively to conservative therapy. If they

are subjected to surgery, however, they should know preoperatively that

postoperative improvement in the power of the long flexors may actually

increase the muscle imbalance in the fingers and cause clawing or make

it worse. Advise such patients that they may require secondary hand

reconstruction for the muscle imbalance if it occurs. For those who

have significant sensory loss, the outlook is somewhat unpredictable

but generally favorable.

hand are candidates for immediate surgery. Fortunately, they are rare

and usually are not seen primarily by the orthopaedic surgeon but more

likely by vascular surgeons.

thoracic outlet is intractable pain. Only the patient can feel and

describe the pain; the surgeon must be able to interpret these reports

appropriately. Constraints of daily routine, vocational or avocational

adjustments, sleep disturbance, and history of analgesic use are all

important avenues of inquiry necessary to formulate a decision for

surgery. A complete and in-depth review of what was done in prior

physical therapy sessions is most important, because the patient may

not have had optimal care, or may actually have gotten worse because of

provocative positioning the exercises require (25).

records. Review the differential diagnosis very carefully before

proceeding. Discuss with the patient and family the mechanics and

objectives of surgery. Explain all possible complications in detail so

that the patient can give an informed consent. If you believe that a

second opinion would be useful, made certain that the surgeon or

physician rendering this opinion has sufficient experience in the area

to provide a valid opinion. Too often that opinion may be rendered on

the basis of little personal experience or knowledge.

lose weight despite specific evaluation for the cause of obesity and

instructions to correct it evinces poor cooperation. I have found it

prudent to inform such patients that their surgery is elective and will

not be done until they demonstrate genuine evidence of being willing or

able to participate in their own rehabilitation.

hemorrhage, the patient’s blood should be typed and cross-matched

before surgery. Whether to operate on a patient who will not accept

blood transfusion or blood products, should they be needed

intraoperatively, is a difficult and individual decision for which I do

not have a confident answer.

local custom, as well as the nature of the surgery to be performed,

either a vascular or general thoracic surgeon may be part of the

operating team. Although I have performed the vast majority of my

surgeries without need for such assistance, it is valuable to ensure

that such help is available on an if-needed basis. For patients who

have particular problems such as successive surgeries in which

complications can be anticipated, consultants may be invited to

participate at the beginning of the case. In addition, the operating

team should be experienced and adequate in number. I require three

scrubbed assistants for surgery by the axillary route. Do not use

overhead arm traction with weights, as is used in shoulder arthroscopy;

it carries a risk of inducing an intraoperative traction injury of the

brachial plexus.

in working order before you make the skin incision. Have vascular and

thoracic surgical instrument packs in the operating room should they be

needed.

the transaxillary route requires that the patient be profoundly

relaxed. The newer, short-acting muscle relaxants are particularly well

suited to this situation. Discuss the time frame for the surgery with

the anesthesiologist before commencing surgery so that muscular

relaxation may be reversed by the time the incision is closed, thus

allowing extubation without delay.

not undertake thoracic outlet surgery because it has the potential for

very serious complications. However, with proper identification of

patients suffering from significant compression and technically

adequate surgery, the results are very gratifying in most cases.

procedure is best for the treatment of TOS. Scalenotomy was the first

procedure to gain favor. If the pathology resided entirely between the

scalene muscles (1,2 and 3),

as was theorized, release of the anterior scalene should have

permanently cured the condition. Unfortunately, the incidence of

recurrence following scalenotomy was sufficiently high that surgeons

had to develop other procedures.

common denominator of compression and have concentrated their efforts

on eliminating it as well as adventitious ribs or congenital bands that

might be encountered in the course of exploration (9).

Since Roos reported his experience with the transaxillary first rib

resection in 1966, this approach has been the procedure most often

performed, and as the mainstay of the surgical approach to the problem,

it is described in detail (28,29,30,31 and 32). A variety of anatomic approaches, however, may be used for exploration of the thoracic outlet and removal of the first rib.

due to fracture angulation or hypertrophic subclavicular callus may

occasionally necessitate claviculectomy. It is worth considerable

effort to retain the clavicle if to do so does not materially increase

the surgical risks (14). Removal of the strut

function of the intact clavicle from a shoulder girdle with poor

muscular support can markedly increase symptoms because of the

superimposed traction effect of the ptotic shoulder. Patients with a

good trapezius may function well following claviculectomy, but they

experience weakness in overhead use of the arm. The enthusiasm for

claviculectomy for uncomplicated thoracic outlet compression has been

very limited. The procedure is not recommended (19).

local pathology. Some authors consider it the preferred method of

surgical treatment in certain cases (31).

Although it is desirable to avoid reattachment of the scalenes to the

bed of the first rib after it has been resected, I do not routinely

resect a portion of the anterior and middle scalenes because of the

possibility of injury to branches of the brachial plexus, which may

actually pass through the middle scalene. The phrenic nerve must be out

of harm’s way if you elect to resect part of the anterior scalene.

recurrence has been deemed due to scarring within the scalene muscles

themselves. An anterior approach is best. In addition to obvious

branches of the brachial plexus and phrenic nerve, the long thoracic

nerve is particularly vulnerable, because it may not always be located

lateral to the middle scalene. It may pierce the muscle or even present

as two branches, each of which must be gently retracted and preserved.

operative approaches to the thoracic outlet specifically for resection

of the first rib and then will comment briefly on the others.

|

|

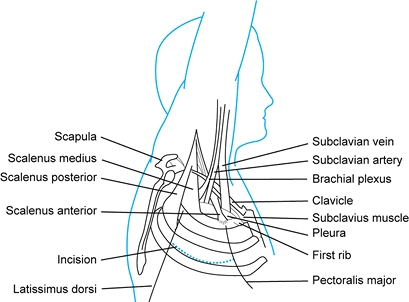

Figure 61.5.

Anatomy of the right thoracic outlet from the axillary view with the upper extremity and shoulder elevated. (From Roos DB. Experience with First Rib Resection for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. Ann Surg 1971;173:429, with permission.) |

-

Place the patient, under general

endotracheal anesthesia, on the operating table in the lateral

decubitus position with the head tilted up. Face the patient’s back. I

place a high standing stool obliquely toward the head of the table near

me so that a sterilely gowned assistant can maintain the arm abducted

during the procedure. This assistant can lower the arm or change its

position as required lest a brachial plexus injury occur from excessive

traction, such as might occur if the arm were suspended from the

ceiling. Two other scrubbed assistants are necessary, one on either

side of the table, to retract the latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major

muscles during the procedure. -

Make a transverse skin incision between

the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi muscles over the third

interspace, just below the axillary hairline. If the incision is

prolonged into the tail or body of the female breast, it can cause a

hypertrophic scar. I spread self-retaining retractors horizontally in

the wound to dissect the fat and render the tissues temporarily

ischemic, thus eliminating the need to ligate superficial vessels. -

Incise the fascia longitudinally in the

midline and bluntly spread the tissues with your fingers. Dissect

through the subcutaneous tissues to the level of the rib cage. Retract

the latissimus and pectoralis muscles. -

Overhead lights will not provide sufficient illumination to perform the surgery safely. Use a headlight or lighted retractors.The intercostobrachial nerve arises from the second

intercostal nerve and crosses the axilla embedded in fat to ultimately

reach the medial aspect of the arm. If possible, mobilize and retract

it, because trauma to the nerve can result in annoying dysesthesia on

the posteromedial aspect of the upper arm and axilla. -

Bluntly dissect with the fingers by touch

until the surface of the first rib can be palpated. Have the assistant

elevate the arm obliquely to open the outlet. -

Ligate the supreme thoracic arterial

branch to allow mobilization of the artery, which is done under direct

vision with nonabsorbable sutures or malleable clips. -

Now identify the important structures in

the field. The anterior scalene muscle attaches to the scalene

tubercle, which is located toward the inner border of the first rib

rather than extensively on its cephalic surface, although occasionally

the muscle may extend over it. Use a small wad or “palm” of gauze and

blunt dissection to delineate the muscle from the adjacent subclavian

artery and vein. -

Have assistants on each side of the table

retract the muscles using Deaver or similar retractors. If the muscle

relaxant wears off, the surgeon and assistants will become aware that

the muscles are getting tighter and the operative field is collapsing.

Close cooperation with the anesthesiologist is vital to the success of

the surgery. -

The most anterior structure in the wound

is the subclavius muscle with the costoclavicular ligaments and their

insertion into the superior surface of the first rib. Just behind and

adjacent to them is the subclavian vein. Use a blunt periosteal

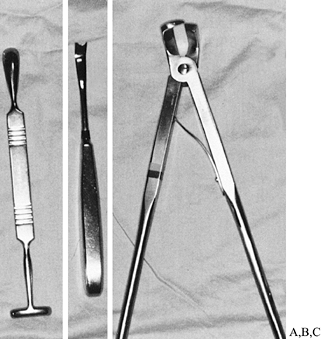

elevator (Fig. 61.6) and dissecting sponges to clear the surface of the first rib of its soft tissues anterior to the middle scalene.![]() Figure 61.6. Instruments for transaxillary first rib resection are shown. Penosteal elevator (A), rasp for first rib (B), and Roos rib cutter (C) are illustrated.

Figure 61.6. Instruments for transaxillary first rib resection are shown. Penosteal elevator (A), rasp for first rib (B), and Roos rib cutter (C) are illustrated. -

Turn attention to the superior surface of

the first rib. Define and detach the anterior scalene. The phrenic

nerve is not usually at risk with this approach, because it is located

at least 2 cm cephalad to the tubercle. Using gentle, blunt dissection,

tease the subclavian artery and vein away from the anterior scalene.

Because the pleura may rise posteriorly and be adherent to the

posterior surface of the muscle, it is helpful to use a long

right-angled clamp to dissect behind the muscle and to shield each

vessel in turn as, alternately, half of the muscle is cut sharply at

its insertion to the bone. Obviously, all of this must be done very

carefully under direct vision. When the muscle has been cut, it

retracts. -

At this stage, visualization is limited

by the middle scalene, which can be elevated off the first rib with the

elevator. It is tempting to sharply divide this muscle at its

insertion, but the possibility of injury to the nerve to the serratus

anterior makes penetration inadvisable. As the muscle is elevated, it

can also be partially retracted with the blunt retractor. -

Using a rasp with a cutting edge that

conforms to the outer curvature of the first rib, separate the soft

tissues from the bone. Often, the first digitation of the serratus

anterior muscle may overlap the insertion of the middle scalene on the

first rib, and it must be bluntly separated. Alternate the rasp, the

periosteal elevator, and gauze sponges to clear the surface of the rib

of its muscle attachments. The undersurface should be similarly

cleared, although it is not desirable to perform the entire dissection

subperiosteally because of the possibility of later regeneration of the

rib, particularly in young patients. -

The periosteum of the first rib must be

disrupted and as much of it removed as possible. This procedure may

result in a tear in the adjacent pleura, causing a pneumothorax. During

this maneuver, ask the anesthesiologist to control respiration so that

the lung is retracted from the pleura in exhalation. About 30 seconds

of apnea should be required. Then controlled respiration may be resumed. -

Flood the wound with normal saline to

demonstrate the integrity of the pleura. If the pleura has been

breached, there will be air bubbles with respiration, or the fluid will

simply funnel down into the pleural cavity. If there is a pneumothorax,

drain it with a soft rubber catheter at wound closure or insert a chest

tube. Usually, a #26 tube can be inserted below the incision and into

the rent in the pleura without difficulty. Connect it to underwater

seal and suction. A pneumothorax does not significantly prejudice the

remainder of the operative procedure, and the tube can be placed just

before closure. It usually needs to be retained for 24 hours. -

Next, address the tendon of the

subclavius muscle and costoclavicular ligament. Make an incision at the

insertion onto the bone, which covers the superior surface of the rib.

Keep the subclavian vein constantly under direct vision because it is

immediately adjacent to the tendon and at significant risk. Once the

plane of dissection has been established, however, it is possible to

use the periosteal elevator and direct it away from the vein as the

tendon is elevated from the rib. Failure to perform this part of the

procedure properly will cause the line of section of the rib to lie at

the level of the subclavian vein, where a sharp edge of bone will

adhere to it. -

Having detached all the important soft

tissue from the first rib, thoroughly explore the outlet for the

presence of fibrous bands that are radiographically invisible but that

may be quite significant in causing compression of the neurovascular

structures. Never retract the neurovascular structures themselves with

any considerable tension because of the very real possibility of

injury. By positioning the arm appropriately, it is possible to lift

the structures off the surface of the rib so that a retractor is

usually not necessary. -

In addition to fibrous bands of various types, other important variations in the local anatomy can be observed (30).

For example, the anterior scalene may actually be overlapped in its

insertion by the middle scalene. There may be additional vascular

branches, or a cervical rib. A complete cervical rib may actually

attach to the manubrium, but a lesser one may reach to the scalene

tubercle. The attachment of the two ribs, which can be fibrous or

actually fused, can create significant problems, especially if the

subclavian artery is located at the juncture.I recently encountered such a situation that had

resulted in a symptomatic aneurysm with emboli in the arm of a

24-year-old woman. After the bone had been removed, I had the valuable

assistance of a vascular surgeon (prearranged) who did a vein graft to

the thrombosed aneurysm, with an excellent clinical result. This

dissection required both a supraclavicular and an infraclavicular

exposure—which is usually not necessary, because most cervical ribs can

be removed without having to make a supraclavicular incision. I always

obtain preoperative permission to make one, however, should it be

necessary. The rib may have to be removed piecemeal with rongeurs

rather than being resectable by means of two neat cuts of a rib cutter.

Piecemeal removal, of course, adds to the time necessary for the

procedure, as well as its difficulty. -

Once the anatomy is clear, decide which

instruments will be used to remove the rib. Ideally, a rib cutter can

be placed posterior to the lower trunk of the brachial plexus, almost

to the level of the transverse process, and the rib can be cut at that

level. If a straight rib cutter is used, however, the resulting

osteotomy will be oblique, leaving a very sharp point on the posterior

portion of rib, a most undesirable situation. For that reason, I have

used the rib cutter designed by Roos (see Fig. 61.6), which produces a transverse cut, owing to the inclination of its cutting surfaces.When used on the left side, introduce the rib cutter

with its point facing upward, hooking it beneath the rib and closing

the jaws before sliding it posteriorly. For a rib on the right side,

the point will face caudad, placing the pleura at risk. In either case,

the jaws should be almost closed and under direct vision so that they

will be safely beneath the neurovascular structures and posterior to

them. During this period, the anesthesiologist should maintain apnea in

expiration. -

After verifying that nothing has been

caught in the jaws of the rib cutter, firmly close the blades and cut

the rib. Then gently slide the instrument forward and open it in the

reverse manner in which it was inserted. Grasp the rib with a Kocher

forceps and visualize the anterior attachment to cartilage. Using a

standard rib cutter with its blades pointed away from the subclavian

vein, divide the rib and gently remove it from the wound. Complete as

close to total rib resection as possible. There should be at least 1.5

cm of space behind the lower trunk of the brachial plexus; in most

patients there will be 2 cm or less of posterior rib fragment

(measuring from the transverse process). Anteriorly, the line of

resection should be medial to the subclavian vein and disarticulation

is optimal. -

At this point, retest the integrity of

the pleura. Achieve complete hemostasis. Digitally explore the outlet

and place the patient’s arm in all positions to assess whether there is

any compression of the neurovascular structures. Usually there is not,

although if the second rib is very prominent, it could cause

compression. Relieve it by removing the middle third of the rib.P.1730If there is a pneumothorax, insert a chest tube at this

point and then prepare for closure. Give antibiotics if there has been

a pleural leak but not in an otherwise uncomplicated case.Return the arm, which the assistant has intermittently

raised and lowered, to the side. Drains are not used, nor should they

be needed.Complete a subcutaneous closure, followed by a

subcuticular closure using nonabsorbable suture, which is removed at 2

weeks postoperatively. Apply a small dressing. A sling is not needed.

thoracic outlet have been advised for resection of cervical ribs and

resection of the first thoracic rib as well as for scalenectomy (3,9,21,22).

In my experience, the exposure obtained for subtotal resection of the

first rib is less satisfactory than that gained with the axillary

approach, although this is not a universally held opinion.

-

Make a 7 to 9 cm incision 1 to 2 cm above

and parallel to the clavicle, extending from the midpoint of the

clavicular attachment of the sternomastoid muscle to the anterior edge

of the trapezius. Identify the platysma muscle for later careful

reapproximation. -

The external jugular vein must usually be

ligated. To facilitate exposure, divide about half of the sternomastoid

anteriorly, just above its insertion; 1 to 2 cm of trapezius may be

similarly cut. Divide the omohyoid muscle at its midpoint. The

suprascapular and transverse cervical vessels run horizontally and must

usually be ligated. -

Identify the phrenic nerve on the surface

of the anterior scalene muscle as it proceeds distally. Carefully

retract and preserve it. Detach the anterior scalene muscle and allow

it to retract. The belly of the muscle may then be safely resected. To

detach the muscle safely, carefully dissect the subclavian artery and

vein away from it and the pleura posteriorly. The internal jugular vein

is on the medial side of the muscle. Mobilize the subclavian artery in

its extraadventitial plane and retract it medially, while retracting

the brachial plexus laterally. -

If a cervical rib is present, remove it

from its periosteal envelope and resect it. Remove as much of the

periosteum as possible. Elevate the middle scalene off the first rib,

and then remove the rib. -

Reserve the transclavicular approach for

postoperative recurrences of thoracic outlet compression in which

adherence of the subclavian artery or vein to the anterior edge of the

resected rib is strongly suspected. -

In the subclavicular approach, make a 7

cm skin incision over the cartilage of the first rib, midway between

the clavicle and second rib (12). Split the

pectoralis major in the line of its fibers, exposing the cartilage of

the first rib. Open the periosteum of the anterior portion of the first

rib with a scissors, and carry out further dissection with a finger or

gauze. -

After the costochondral junction is

divided, remove the cartilage with a rongeur. The rib may then be

grasped and levered, either caudally or cephalad, for stripping of the

anterior and middle scalene muscles. Use a rasp, if necessary, to

denude the rib further, then cut the rib posteriorly with Sauerbruch

rib shears.

any abnormalities of the first rib encountered, including abnormal

width or a cervical rib, are difficult to manage because of limited

access. The presence of anomalous bands cannot be easily verified or

dealt with, and the vessels must be constantly retracted and are at

risk in an extremely confined space. Other than for access to the

anterior portion of the first rib, this is not a useful incision and is

not recommended.

Although it is considered a technique that does not involve any

disability or disfigurement, it is an extensive approach that traverses

the trapezius muscle, the levator scapulae, and rhomboids. For this

reason, I believe that it should be used infrequently; it should

particularly be avoided in patients who already have weakness of these

muscles and sagging shoulders, as well as those who must do heavy labor

following their convalescence.

|

|

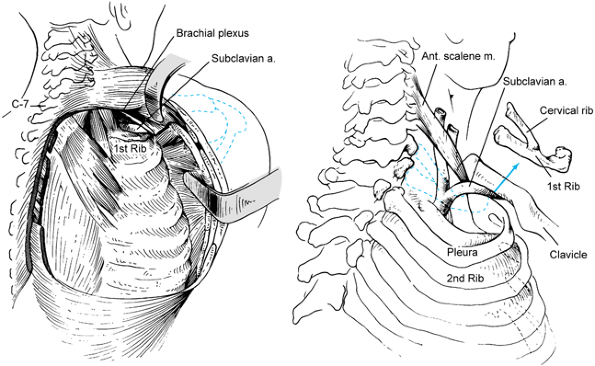

Figure 61.7. A: Posterior approach for resection of the first thoracic rib is shown. B: A cervical rib has been removed with the first thoracic rib. (From Clagett OT. Presidential Address: Research and Prosearch. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1962;44:153, with permission.)

|

decompression of the thoracic outlet in patients who are extremely

muscular or obese and in whom the axillary approach would be

technically difficult. It is the preferred approach for reoperations in

which a retained posterior segment of rib has become adherent to the

brachial plexus and is causing symptoms.

-

Place the patient in the lateral

decubitus position, with the affected side up. Prep and drape the arm

free. Drape the entire hemithorax posteriorly past the midline,

including the neck to the hairline. -

Make a long incision from the superior

angle of the scapula, 2 cm medial to its vertebral border, for the

length of the bone. An incision too close to the scapula will encounter

the anastomotic scapular vessels, causing annoying bleeding. -

Introduce a scapular retractor beneath the scapula, which can then be retracted anteriorly and laterally (see Fig. 61.7).

-

The first rib must be identified from the

level of its transverse process; the rib is not horizontal in most

patients, and the second rib may partially obscure it. The posterior

scalene may blend with the middle scalene and is attached to the outer

surface of the second rib. It is easily detached. Identify and

carefully section the middle scalene, which inserts onto the superior

surface of the first rib. Anterior to it, the lower trunk of the

brachial plexus lies in contact with the rib, with the subclavian

artery immediately anterior to it, restrained by the insertion of the

anterior scalene to the scalene tubercle. The first digitation of the

serratus anterior originates from the outer aspect of the first rib and

can be freed with a rasp. The subclavian vein is, of course, anterior

to the anterior scalene and must be carefully protected. -

Remove the first rib. If a cervical rib

is present, it can be easily removed through the same incision. It is

impossible, however, to deal with a subclavian aneurysm through this

approach. Although the rib is resected subperiosteally to protect the

adjacent structures, remove as much of the periosteum as possible to

prevent regeneration of the bone. -

If a pneumothorax has been produced, insert a chest tube.

-

Perform closure in layers, taking care to

approximate anatomically the very important suspensory muscles of the

scapula, including the levator scapulae, rhomboids, and trapezius.

Place the patient in a sling for 3 weeks postoperatively and then begin

exercises to strengthen shoulder girdle muscles.

thoracic outlet by the axillary route, there is minimal blood loss and

physiologic disturbance. Although there may be moderate postoperative

pain, within a day most patients are sufficiently comfortable to move

about without the support of a sling. If a pleural tear has occurred

intraoperatively, then a chest tube is used for 24 hours. Most patients

are discharged from the hospital on the second or third day after

surgery.

to a single layer of gauze or removed altogether. Patients may shower

as long as the wound is kept dry; underarm deodorants and powders are

prohibited until the sutures are removed. Patients may be ambulatory at

home but are cautioned against heavy lifting or any strenuous

activities

for 4 weeks after surgery. Then they may resume their preoperative

exercise program, if there is no significant postural abnormality or

weakness of the scapular muscles. It is most important that these

exercises do not involve either overhead use of the arms or shoulder

bracing, because both of these types of exercises essentially duplicate

the provocative maneuvers that are used in diagnosis. Unfortunately,

they are still prescribed and used in many physical therapy facilities (25).

from the surgeon’s inexperience or timidity. Failure to resect the

subclavius tendon anteriorly produces a line of resection of the first

rib at the level of the subclavian vein that will then adhere and cause

symptoms of venous compression. Because the vein has a thin wall and is

easily torn, reoperation is hazardous. It is best performed, if

necessary, by the transclavicular route.

the lower trunk of the brachial plexus by 2 cm is most common with an

anterior approach, but it may also occur with a transaxillary

procedure. In most cases, less than 2 cm of rib should remain from the

level of the transverse process, but it is unnecessary to disarticulate

the rib. If recurrence is believed to be due to adherence of the lower

trunk of the plexus to the rib remnant, this problem is best approached

through a posterior, high thoracoplasty approach (8,41).

The hazards of this procedure stem from the difficulty of separating

the periosteum and scar from the nerves, which must be carefully

defined and lysed while the rib remnant is removed. Preliminary

resection of the second rib is an aid to the dissection, which then

proceeds to the bed of the first rib with a wider and clearer field.

regeneration of a resected rib, particularly in a young patient, it is

advantageous to remove or displace as much of the periosteum as

possible. The close adherence of the pleura, however, makes rents in

this filmy structure common during the course of the dissection.

Because the pleura cannot be directly repaired, either a rubber

catheter may be used to drain the pleural cavity during closure and

then withdrawn, or a chest tube may be placed through a separate stab

wound and connected to underwater suction for 24 hours. Then, after a

radiograph confirms the absence of a pneumothorax, the tube may be

removed. If a patient has sustained an intraoperative pneumothorax, he

or she should be restricted from air travel for 7 to 10 days.

the subcutaneous tissues of the arm and innervates the posterior

brachium, in many patients, down to the level of the olecranon. Because

it is located at the midpoint of the axillary incision made over the

third interspace, it is liable to injury, either by laceration or

traction. Even if care is taken to protect it, in many cases, there is

some transient numbness along the posterior aspect of the arm, which

gradually fades with time. If the nerve is cut, however, the patient

may experience very annoying dysesthesia that can be permanent.

Prevention is the best means of dealing with the problem. If there is a

neuroma, local nerve blocks are of occasional value.

Occasionally, patients have varying degrees of neural dysfunction in

excess of what was present preoperatively. The patient with increased

postoperative loss of intrinsic function in the hand and numbness of

the little and ring fingers may have sustained either a direct

laceration of the lower trunk or a traction injury. In the first

situation, repair is impossible, and no improvement is expected. In the

second situation, often there is little spontaneous recovery, although

it may occur. This complication can be avoided by gentle handling of

the nerves with minimal or no direct retraction.

the entire arm and significant motor weakness that was not present

preoperatively has sustained a traction injury to the brachial plexus,

which usually results from excessive pull on the arm during surgery.

This complication can result in permanent neurologic loss and pain, and

can largely be avoided by carefully monitoring the amount of

intraoperative traction. During the procedure, arm traction must be

periodically lessened so that a constant pull is not maintained.

comes around or through the middle scalene can result in permanent

winging of the scapula owing to paralysis of the serratus anterior (48).

The nerve should be sought and carefully protected. Sometimes, separate

branches to the digitations of the serratus anterior are seen, in which

case these must

be preserved. This complication weakens the patient’s ability to lift the arm in front of the plane of the body.

any procedure performed within the thoracic outlet. The surgeon must

have available appropriate technical ability or surgical assistance for

all eventualities. As stated earlier, appropriate instruments must be

present in the room, and the sterile field should be draped to allow

for additional procedures, including thoracotomy, if necessary.

demanding, sometimes frustrating, and technically challenging. However,

many carefully selected patients get good results from surgical

treatment when conservative therapy has been strenuously employed and

failed. The nature of the patient population is such that attempting to

compare the results of different series of surgically treated patients

can lead to markedly divergent impressions of the effectiveness of

surgery. In my own experience, about three quarters of the patients

that I have operated on have had good to excellent results. Despite the

fact that these surgical patients represent less than 20% of all the

patients I have seen with this entity, I believe that the surgery of

TOS has a rightful place in the armamentarium of orthopaedics.

scheme: *, classic article; #, review article; !, basic research

article; and +, clinical results/outcome study.

AW. Cervical Ribs: Symptoms, Differential Diagnosis and Indications for

Section of the Insertion of the Scalenus Anticus Muscle. J Internat Coll Surg 1951;16:546.

MJ, Olney RK, Parry GJ, et al. Relative Utility of Different

Electrophysiologic Techniques in the Evaluation of Brachial

Plexopathies. Neurology 1988;38:546.

P, Kazmier FJ, Hollier LH. Axillary-Subclavian Venous Occlusion: The

Morbidity of a Non-Lethal Disease. J Vasc Surg 1986;4:333.

Forestier N, Moulonguet A, Maisonobe T, et al. True Neurogenic Thoracic

Outlet Syndrome: Electrophysiological Diagnosis in Six Cases. Muscle Nerve 1998;21:1129.

A, Papagapiou M, Vanderlinden RG, et al. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome after

Motor Vehicle Accidents in a Canadian Pain Clinic Population. Clin J Pain 1995;11:316.

S, Paradiso C, Giannini F, et al. Diagnosis of Thoracic Outlet

Syndrome. Relative Value of Electrophysiological Studies [see

comments]. Acta Neurol Scand 1994;90:179.

AP, Ignacio DR, Gargour GW, et al. Assessment of Conduction from C8

Nerve Root Exit to Supraclavicular Fossa—Its Value in the Diagnosis of

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. Electromyog Clin Neurophysiol 1989;29:445.

DM, Wassel HD. Traffic Accident Induced Thoracic Outlet Syndrome:

Decompression without Rib Resection, Correction of Associated Recurrent

Thoracic Aneurysm. Int Surg 1993;78:25.

RD, van der Merwe DM, Mitchell WL. Subclavian Vein Stenosis and

Axillary Vein “Effort Thrombosis.” Age and the First Rib Bypass

Collateral, Thrombolytic Therapy and First Rib Resection. S Afr Med J 1987;71:564.

T, Trojaborg W. Diagnosis of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. Value of Sensory

and Motor Conduction Studies and Quantitative Electromyography. Arch Neurol 1987;44:1161.