Outcomes Assessment

the formulation of a hypothesis, testing a sample to prove or disprove

its validity, and applying the principle tested to the entire

population. Adherence to this process reduces bias and promotes valid

interpretation of data. Testing of the hypothesis requires the

appropriate experimental design and measurement apparatus. Process improvement (quality control)

is a closed-loop system in which a problem is identified, a remedy is

selected, data on the effectiveness of the remedy are collected, and

the remedy is assessed and either modified or continued based on the

data collected.

the clinical practice of medicine. The outcome initiatives were started

in the late 1980s as a response to the rising cost of health care.

Regional variation in rates of surgery, especially for the treatment of

spinal problems, pointed out the need to assess the results of

treatment and formulate a best method for appropriate patient care.

Only with “hard” data can one choose from the multiple options

available to select the best care for a given problem. In addition,

insurers are assessing process quality through the use of health

employer data and information set questionnaires and other outcome

measures. New initiatives are under way to use quality incentives to

stimulate better patient care through financial remuneration based on

outcome measures of quality.

outcomes assessment tools is simply to find the best treatment for the

patient. Rothman used the SF-36 health status questionnaire to prove

the high level of improvement that came with total hip arthroplasty and

compared these outcomes with surgery for herniated disc, total knee

arthroplasty, and scoliosis. Surgery for disc herniation showed the

second best improvement, with total knee arthroplasty third. Patients

operated on for scoliosis showed deterioration in health status.

to show that an anterior approach to curve correction had better

acceptance and patient-perceived result than posterior correction for

equivalent curves; this was despite the “objective” outcome of solid

fusion and percent correction seen by the operating surgeons. An

additional study by D’Andrea compared the radiographic outcome of

scoliosis patients with this patient-based outcomes questionnaire and

showed little correlation between the surgeon’s success criterion and

the patient’s self-perception. These examples show the power of

outcomes research.

evaluation uses an outcomes instrument for periodic reassessment of

practice patterns, usually with comparison to a large group of similar

patients. The outcomes assessment movement had a surge in the 1980s and

1990s with varied success.

have kept outcomes records on their surgical patients with an easily

definable end point (i.e., survival); this has been a reaction to

outside surveillance but has led to quality improvements for cardiac

surgery patients. In spinal surgery, the North American Spine Society

first presented its low back outcomes instrument in 1991. This

instrument was an effort by a committee within the group to propose a

questionnaire that would be accepted generally for use in low back

patient analysis. The instrument was designed to measure pain and

function, employment status, expectation, and success of meeting the

expectation. The instrument development followed the principles

outlined subsequently.

incorporated this instrument into its MODEMS database, while at the

same time a private group, the National Spinal Network, formulated its

own instrument set. In the latter part of the 1990s, both groups came

together in accepting the MODEMS data set as a standard. Although the

National Spinal Network still is functioning, the AAOS MODEMS project

has ceased to exist as a data-gathering and comparative group.

that perform outcomes assessment. The inherent bias in this approach

may be overcome through the use of accepted instruments and independent

analysis of the data.

the data set affects the accuracy of the conclusions drawn from it.

Pitfalls include the office mechanics of data collection, expense of

data entry, privacy, and concern regarding the end use of the data

collected.

completes, with subsequent key data entry into the computer. The

general patient population must accept the instrument selected.

Kiosks

and computer data tablets have been tried but rely on the

sophistication of the end user (patient) and have no way of

verification of accuracy. Native language of the patient must be

considered so as not to introduce a translation error.

where most of the patients are seen for consultation and only a small

portion go on to surgery, a decision must be made to distribute the

forms economically. If all patients receive and complete one, many will

be discarded if the patients are seen for one consultation only. If

forms are given to patients selected for a procedure, it may be late in

the process (i.e., the patient may be tired), and the completion rate

and accuracy may suffer. Optimal use would be incorporation of a

smaller form within a general patient intake form with a longer one for

patients selected for a procedure of interest. Having a single staff

member responsible for the tracking is ideal; if the surgeon reviews

the form at some point during the interview, this adds to the success

of the project.

assess the current patient or group of patients. Consideration of the

patient’s privacy prevents dissemination of identifying data; yet if no

identifying data are sent to the data repository, the same patient may

be duplicated. This bias can occur when the same patient completes

another data set in a second participating physician’s office.

Solutions to this problem include unique identifiers from combinations

of patient-identifying data (e.g., part of birth date plus part of

social security number) or by comparing the patient with a set of

normative data at any given point in time.

Foundation established by the Maine Medical Association. This group was

federally funded and would send nurses to participant offices to

contact patients directly and have them complete questionnaires and

analyze the data obtained. The group showed the usefulness of surgery

for herniated disc and spinal stenosis. Funding was insufficient to

allow further study of spinal fusion, however, and the project has

since disbanded.

to their detriment has been a factor in the limited success of these

projects thus far. Although studies have shown that the anonymous

presentation of data to physicians has led to beneficial change in

rates of procedures, there still seems to be a reticence to participate

in pooled outcomes data unless it has been mandated.

-

General health status

-

Region (or disease) specific

Ware, and the Musculoskeletal Functional Assessment, championed by

Swiontkowski. Examples of the latter are the Oswestry Disability Index,

the North American Spine Society (NASS) Instrument, the MODEMS

instrument from the AAOS, and the Scoliosis Research Society instrument.

appropriate, accurate, sensitive, and accepted device to assess the

situation. For patient-based outcomes instruments, this process has

been recognized as follows:

-

An expert panel is assembled to select appropriate items.

-

A pilot test is run, and the results are assessed to reduce the number of items.

-

The test is given to groups of patients,

and a retest is given a short time later to ensure reliability; Pearson

coefficients >0.05 are preferred. -

The range of responses is analyzed to

avoid clustering, and analyzing edge effects tests validity. Cronbach’s

a coefficient, a measure of item applicability in a scale, >0.86 is

preferred. -

Sensitivity to change is assessed by analyzing pretreatment and posttreatment groups.

if one is to apply the instrument across a population of patients. In

addition, cultural issues have to be assessed for applicability of the

instrument to a diverse patient population or for international

application. Finally, an assessment of normative results (i.e., results

obtained from a group of “normal” individuals) may strengthen the

usefulness of the instrument. A comprehensive review of these

instruments was undertaken by NASS. Their Compendium of Outcomes

Instruments is recommended for review before making a selection.

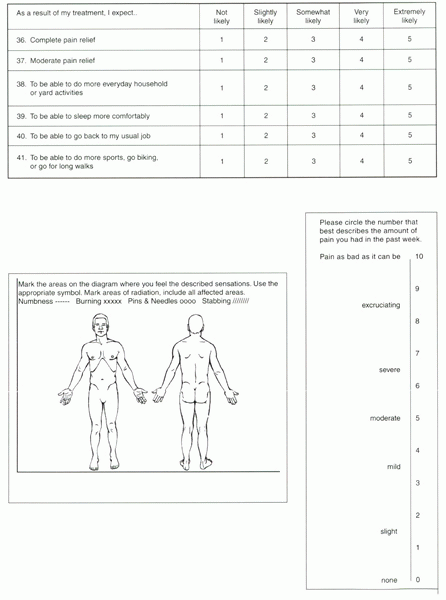

method of assessing patient condition. Since that time, numerous

articles have appeared assessing the strengths and weaknesses of pain

diagrams. The best more recent summary is by Ohnmiss. The diagram

consists of anterior and posterior outlines of the body with patients

asked to draw symbols indicating the location and the nature of their

pain. Symbols usually are given for ache, numbness, pins and needles,

stabbing, and burning. When Palmer first reported the diagram, a simple

observational characterization of the response in organic and

nonorganic terms was proposed. Uden expanded this classification into

subgroups: organic, possibly organic, possibly inorganic, and

inorganic. Intraobserver reliability was 85% for senior observers and

77% for junior observers. Ransford published a penalty point scoring

system in which points were assigned for pain not in usual locations

seen for root compression and other “commonly encountered causes of

back and leg pain.” High reliability has been reported with the use of

this method. Margolis used a scoring method based on the method used in

burn centers to evaluate extent of injury; a grid was placed over the

drawing, and if a mark was placed in that region, a point was scored.

Minnesota Multi-Phasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) was 89% overall

with a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 79%. Although Uden

showed the pain diagram correctly predicted herniated disc on

myelography, Rankine showed poor prediction of root compression seen on

magnetic resonance imaging. Mckoy found a significant negative

correlation between pain drawing scores and outcomes 6 months after

surgery. The pain diagram has been found to have a significant

correlation with MMPI hysteria scale and presence of Waddell criterion,

both of which have a negative correlation with surgical success, so

this result in not unexpected. In her summary publication correlation

with discogram findings, Ohnmiss showed that the location of pain

indicated on the diagram was related to the symptomatic level of the

disc. In L3-4 disruption, pain was distributed in the anterior portion;

L4-5 pain was distributed in anterior and posterior portions; and L5-S1

pain was distributed in the posterior portion. It seems that the best

use of the pain diagram is in identifying patients with inorganic pain

and patients with radiculopathy. There may be a correlation with the

level of disc disruption.

usually labeled from 0 to 10 on which the patient is asked to rate his

or her pain. Adding gradations to create a ruler has expanded this

system, and images have been added to facilitate patient selection. It

is a simple and effective method to allow the patient to rate the

amount of pain and compare pretreatment and posttreatment levels.

Million et al reported the test-retest reliability of this specific

version of the visual analogue scale. They showed r = 0.88 for each of the individual scales and r

= 0.97 for the total in a test administered by an examiner. The test

has been correlated with isokinetic and nondynamometric tests.

instrument designed to assess a patient’s well-being. It was developed

by Ware et al in 1984 for a Harris survey and later modified for a

medical outcomes study. The SF stands for Short Form

because participants did not complete earlier questionnaires that were

deemed too long. The 36 questions are divided into eight domains or

scales (Table 34-1).

|

TABLE 34-1 SHORT-FORM 36

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

administered by a qualified professional. As such, it does not perform

as an outcomes instrument but as a test that has been studied and

associated with prediction of surgical outcomes. It originally was

described in 1942 by Starke and has been modified by Butcher. There are

10 scales generated from a questionnaire of 360 to 570 questions. Most

important for the spine patient are the hysteria, hypochondriasis, and

depression scales. Normative and other testing has been carried out for

this instrument.

It has been modified to a version 2.0, in which the question regarding

pain intensity has been changed from that of medication usage to

intensity. The score is a disability score, and a higher score implies

more disability, which sounds counterintuitive. The instrument has been

shown to have high test-retest reliability and has been validated

against the Roland-Morris Questionnaire. The scoring is a simple

addition of the responses, then doubling. Change greater than 15% is

considered significant. The instrument’s primary author has published a

review of its use and functionality. The test has been criticized in

that the result is counterintuitive; a higher numeric score indicates

more disability and a patient that is faring poorly. Nonetheless, its

simplicity, length, and acceptance have made it a valuable test.

an outgrowth of the Sickness Impact Profile and first was reported in

1983. It is a 24-question yes/no format describing back pain; brevity

and ease of understanding by the recipient are its hallmark. The

Sickness Impact Profile on which it is based has been studied

extensively; this instrument still is relatively untested.

|

|

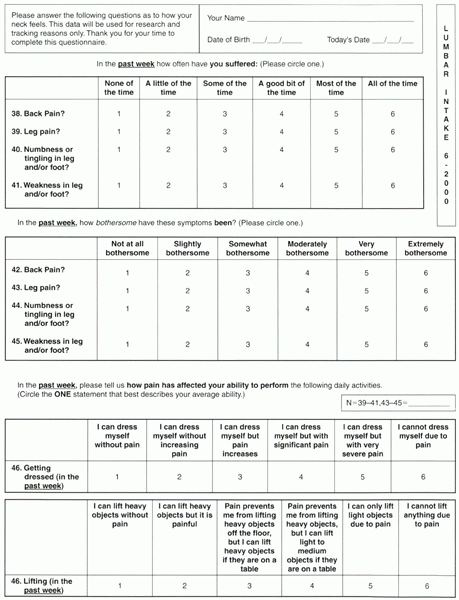

Figure 34-1 Part 1.

|

|

|

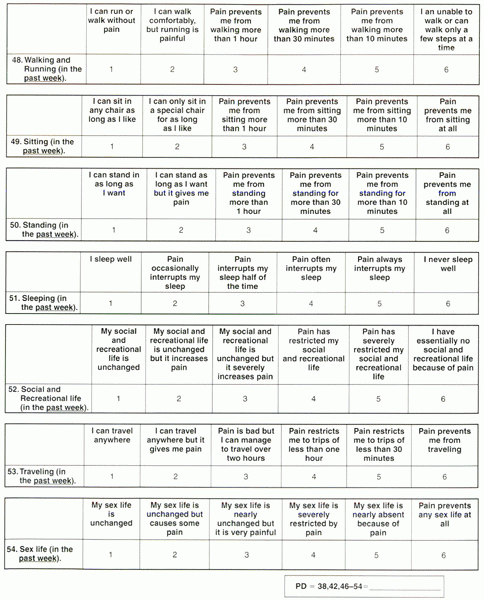

Figure 34-1 Part 2.

|

|

|

Figure 34-1

Part 3. Example of an office-based low back outcomes instrument. The NASS pain disability score is calculated by averaging items 38, 42, and 46 through 54. The neurologic impairment score is calculated by averaging items 39 through 45. The expectation score is calculated by taking the average of the responses in that area (items 36 to 41). The pain diagram and visual analogue scale stand alone. |

by a committee of the NASS and first formally reported in 1996. The

committee added to the Oswestry base questions concerning amount of

back pain to form a pain score. Six additional questions concerning

amount of and bothersomeness of leg symptoms created a neurologic

score. Both scores were an average of the responses to the individual

questions that made up the scale (range 0 to 5). A lower score

indicates a better functioning patient. Finally, there were questions

regarding expectations for outcomes (for the intake form) and

satisfaction with treatment (for the follow-up form). The instrument

was psychometrically studied with good validity and reliability

characteristics.

|

TABLE 34-2 NURICK CLASS

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

TABLE 34-3 JAPANESE ORTHOPEDIC ASSOCIATION MYELOPATHY SCALE (MAXIMUM SCORE 5 17)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

complete set of musculoskeletal outcomes instruments that could be used

for any musculoskeletal outcomes research or assessment. For the spine,

the instrument design phase of the project was coordinated with various

subspecialty societies under the auspices of the Council of Spine

Societies. The NASS low back pain outcome instrument was the basis for

the MODEMS spine instrument. The low back module was kept intact with

minor modifications. For the cervical spine, the instrument was

reworded, changing “back” to “neck” and “leg” to “arm.” Parallel scores

(i.e., pain disability and neurologic impairment) were established. An

attempt was made to add scales to measure myelopathy by questioning

stiff and shaky leg symptoms. In addition, questions to assess

comorbidity and an associated scale were constructed. Finally, the

SF-36 was added, and a pain diagram substitution was created. The

expectation scale and the expectation-met scale were retained from the

NASS instrument. All scores were “normalized” to a 0-to-100 scale with

higher numbers indicating better function or a patient in better

condition. The questionnaires have undergone validity

and

reliability testing, and normative data have been obtained. In

addition, a scoliosis questionnaire was devised that measured the

patient’s view of their attractiveness (cosmesis); this was added to

the low back questionnaire.

|

TABLE 34-4 FRANKEL SCALE

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

overall MODEMS data-gathering project. The above-specified additions

resulted in a lengthy questionnaire. The MODEMS questionnaires have not

been widely accepted and have been criticized on the basis of length of

instrument and arduous nature of data entry. In addition, they were

part of a project to pool data in a central repository that suffered

from poor participation. Nonetheless, it is a worthy effort, and one

can use selected parts to create valuable scales that can provide

helpful data. The normative data were obtained by administering the

questionnaire to people selected by a research firm to represent a

normal cross section of the population. This is the first instrument to

have this feature and provides a benchmark against which the patient

can be measured.

measures cervical outcomes. Good validity and reliability data were

reported. The questionnaire is about as long as the MODEMS instrument

without the SF-36 and the comorbidity questions. Excellent patient

acceptance was reported. No scale has been created with the measure,

but the questions stand independent of each other.

|

TABLE 34-5 AMERICAN SPINAL INJURY ASSOCIATION MOTOR SCORE

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

measure impact of deformity on patients with scoliosis. The validity

and reliability testing of this instrument was coupled nicely with a

study of anterior versus posterior approach to the correction of curve

and indicated a preference for the former approach. The questionnaire

has been modified by Asher but with minimal change. It seems to be most

valuable in adolescent patients, but more recent reports showed its

response to patient condition and that its ceiling and floor effects,

internal consistency, reproducibility, and validity were equal to or

better than the SF-36 domains with which it was compared.

physical examination parameters to assess the status of the patient.

The Japanese Orthopedic Association myelopathy scale and Nurick

classification are valuable for degenerative conditions. The Glasgow

Coma Scale, the Frankel classification of quadriplegia, and the

American Spinal Injury Association classification are examples of this

type of assessment item for a patient after trauma to the spinal cord.

extremities, feel sensation in trunk and extremities, and control

bladder function. It has been modified for use in Western countries by

substituting use of knife and fork for chopstick use. Numerous

publications have cited the scale, but there has never been a

scientific test of its sensitivity and specificity.

|

TABLE 34-6 GLASGOW COMA SCALE

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

He divided this gradation into motor useful and motor useless. This

scale is useful in tracking a patient’s progress or regression during

the course of therapy. The American Spinal Injury Association expanded

on the Frankel classification. The same level of function for each

individual motor group is retained, but key muscle groups are

identified, and a point score is given for each side (Table 34-5).

A separate notation of bladder and bowel function and the lowest

sensory level present are noted. The classification provides a valuable

way of tracking a patient’s progress. Finally, in tracking the trauma

patient, the Glasgow Coma Scale is a valuable adjunct because a patient

with spinal injury often has a concomitant head injury that requires

assessment (Table 34-6).

M, Min Lai S, Burton D, Manna B. Discrimination validity of the

Scoliosis Research Society-22 patient questionnaire: relationship to

idiopathic scoliosis curve pattern and curve size. Spine 2003:28: 74-82.

M, Heller J, Ducker TB, Eisinger JM. Cervical spine outcomes

questionnaire: its development and psychometric properties. Spine

2002;27:2116-2123.

M, Bobbitt RA, Pollard WE, et al. The sickness impact profile:

validation of a health status measure. Med Care 1976;14:57-67.

CW, Goldman S, Ilstrup DM, et al. The pain drawing and Waddell’s

nonorganic physical signs in chronic low-back pain. Spine

1993;18:1717-1722.

LH, Cats-Baril WL, Katz JN, et al. The North American Spine Society

lumbar spine outcome assessment instrument, reliability and validity

tests. Spine 1996;21:741-748.

LP, Betz RR, Lenke LG, et al. Do radiographic parameters correlate with

clinical outcomes in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis? Spine

2000;25:1795-1802.

RB, Doxey NC. A prospective investigation into the orthopedic and

psychological predictors of outcome of first lumbar surgery following

industrial injury. Spine 1984;9:264-268.

JCT, CouperJ, Davies JB, O’Brien JP. The Oswestry low back pain

disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy 1980;66:271-273.

TR, Gorup JM, Shin TM, et al. Results of the Scoliosis Research Society

instrument for evaluation of surgical outcome in adolescent idiopathic

scoliosis: a multicenter study of 244 patients. Spine 1999;24:1435-1440.